I wrote this in the middle of the year but for some reason never posted it. I found it again doing some end of year tidying. It seems as relevant now as it was then.

The economist Adam Tooze has an article on his newsletter assessing the cost of getting to net zero in Europe by 2050. It’s based on a close reading of a McKinsey report and a look at some of the assumptions in the technical report produced for the EU Commission.

There’s also a question of political philosophy sitting underneath this inquiry, and a question for futurists:

What does it mean to face up realistically to the challenge of climate change? Under present conditions, what is it realistic to hope for? Not the least mind-blowing thing about climate politics is that we are forced to rely on scientifically founded speculation about the long-distance future. That makes it particularly interesting as a domain for talking about realism.

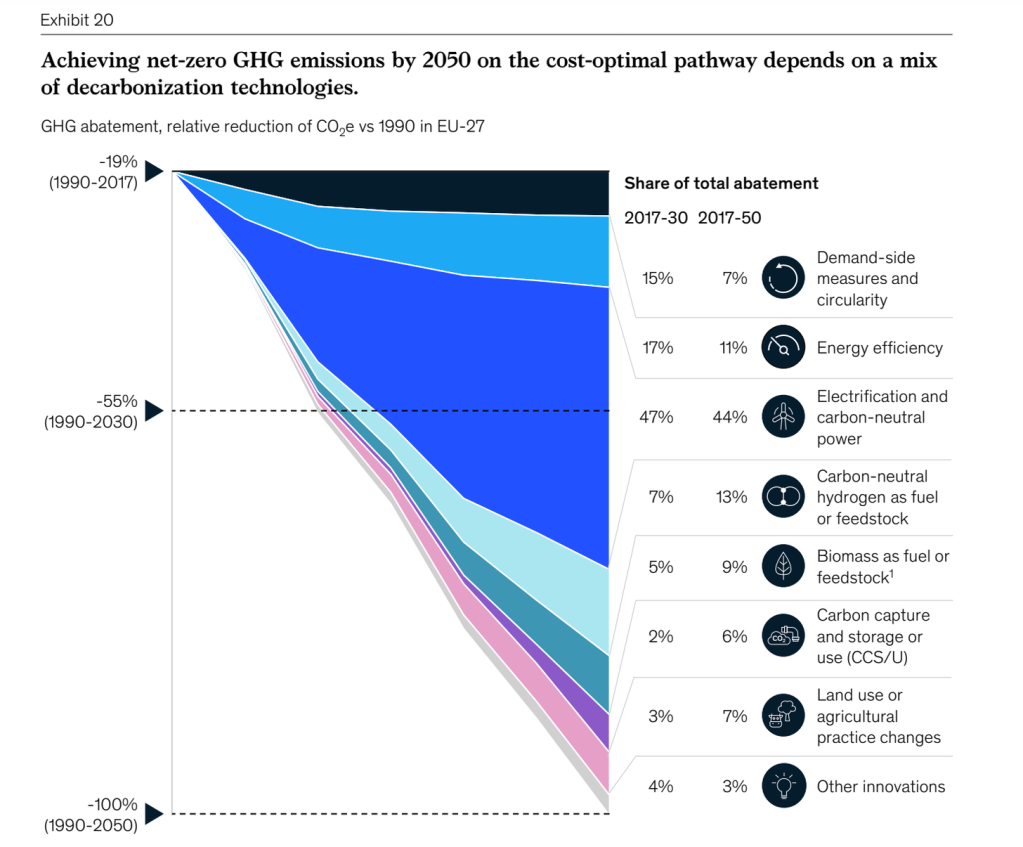

Obviously decarbonisation represents a huge technological shift, but not one that involves untested technologies. Looking out to 2050, 87% of the necessary emissions cuts could come from technologies that are already in the market, or at the very least, exist at the demonstrator stage. At the same time the headline financial numbers are vast—in the tens of trillions of Euros. McKinsey calculates €28 trillion between 2020 and 2050, the EU €28.4 trillion between 2031 and 2050.

Financing transition

But, of course, investment is a flow, not a stock. Current EU GDP is €24 trillion a year, and investment runs at just over 20% of GDP. McKinsey reckons that to fund the transition, the EU needs to invest 5.8% of GDP per year in transition. And much of investment cost of decarbonisation is not new money:

As Joerg Haas has argued, overcoming our addiction to fossil fuels implies stamping on the brake at the same time as hitting the accelerator.

In fact, four-fifths of this can be covered by redirecting money away from the fossil fuels sector. After this, the additional cost of transition investment is of the order of 1-1.5% of GDP. And McKinsey argues that this will be covered by energy savings from the transition: the cost of getting to net zero is zero.

Rates of return

If this seems a little too good to be true, it probably is. Investment generally has to be justified by a rate of return, or—if there isn’t one—subsidised by someone. At current carbon prices, McKinsey argues, the return on quite a lot of transition investment is hard to identify, especially in the built environment and industry.

It’s also worth noting that Tooze isn’t acting as a McKinsey apologist here: instead he’s reading its report as a performative document on behalf of capital—an opening shot in the transition negotiations, as it were.

Behaviour change

One thing that immediately changes the investment assessment, however, is proper carbon pricing. As soon as the carbon price gets to €100/tonne, 80% of this low return investment can be justified by conventional business assessment of returns.

It’s also worth noting that, like other policy analysts, including those of the EU, McKinsey’s analysis assumes that there will be no behavioural change. But they have done the sums on what this might add up to:

Less traveling and more sensible use of energy at home could help. So too could a shift away from meat-eating. Any one of those changes would swing the balance a percentage point here or there. According to McKinsey’s model, a suite of behavioural changes could reduce EU emissions by 15 per cent, substantially helping to close the gap as far as the hardest to abate sectors are concerned.

It’s a long piece, and there’s a lot more in it. On the downside, vested interests can delay necessary change for longer than anyone else thinks is reasonable, and even diverting investment from the fossil fuels sector may be harder than it should be. But—as a climate change pessimist—I came away from this piece more optimistic than when I started it.

The geopolitics of energy

And as it happened, Adam Tooze and Helen Thompson ended up talking about transition in an episode of the podcast Talking Politics. Thompson had just had an article on the geopolitics of energy transition published in Engelsberg Ideas, which certainly got a lot of love at the time on my various feeds.

It’s a commonplace that oil has shaped a lot of geopolitics over the last century. (There’s a great summary of this history in Thompson’s article.) Thompson’s question is about what the geopolitics of renewables might look like. Although one answer is that production of renewable energy becomes much more distributed, the renewable supply chain and its materiality gets locked into geopolitical considerations.

And our economies are currently completely dependent on the flow of oil. Between 1995 and 2019 the share of primary energy consumption accounted for by fossil fuels fell a whole two percentage points, from 86% to 84%. Declines in fossil fuels seem to be associated with slowing growth, although its not sure which way causality lies. BP estimates that in 2040 the world will still be using 80-100 million bpd. (It may not be a dispassionate observer, of course, and this doesn’t square with the investment exodus from the oil sector).

Energy density

Thompson also makes a lot of Vaclav Smil’s observation that the coming energy transition is quantitatively different from previous energy transitions, because it involves a shift to a less dense energy source (wood to coal, then coal to oil, were transitions to denser energy sources).

I think she makes too much of this, for two reasons. The first is that the density is only essential to some technologies, such as the plane; we could easily have had electric or steam cars as a dominant form a century ago, had technology pathways turned out differently. Cars ended up being designed for dense energy because there was a lot of it about.

The second reason is that the economics of energy are more determined by EROEI, the energy return on energy invested. This is currently plummeting for oil and increasing for renewables, at the same time as the cost performance of renewables is racing ahead.

The China question

This doesn’t change her geopolitical argument, however. However you look at it, China is central to this because of its global market position in the solar sector. We’re also going to see competition for essential battery components like lithium and cobalt, some of which comes from conflict zones. (This turns up, incidentally, as a plot point in Adam McKay’s satirical film Don’t Look Up.)

So, immediately, we see faultlines in America’s relationship with China, which needs an effective trading relationship with China if Biden’s transition plan is to work. As far as Europe is concerned, it needs to keep China close for the same industrial reasons while looking away from democracy abuses in Hong Kong and China’s suppression of the Uighurs.

The other question is a question of domestic politics:

Merkel has observed that this attempted energy revolution ‘means turning our backs on our entire way of doing business and our entire way of life.’ In its 2019 ‘Clean Growth’ report, the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee noted ‘in the long-term, widespread personal vehicle ownership does not appear to be compatible with significant decarbonisation’.

Access to mobility

Technically this is probably right. It’s not at all clear that we will have enough batteries to replace our current combustion engine car fleet with electric vehicles. And although our attachment to cars is waning—we tend to see them as functional vehicles rather than status symbols—that hasn’t stopped the market from chasing after large heavy SUVs to maintain margins.

The energy transition does challenge a century of assumptions about the access of individuals to mobility, from the Shell Guides onwards.

Thompson also sketches out a third challenge here. When we start to think about the energy basis of the prosperity of the rich world, and the costs that were involved in producing it, ethical issues emerge quickly. These won’t disappear in a renewable powered world.

As an aside she doesn’t mention the challenge of this energy origins story to Western ideas about innovation, progress, and so on, although it lies below the surface of her narrative.

Her conclusion is a tough one:

Western democracies need practical strategies to accelerate technological innovation in renewables, batteries, and carbon capture as well as to address the coming problems around the supply of oil. They also need political strategies to contain the distributional consequences of reduced long-term energy consumption. That what is necessary pulls in opposite directions is one of the great burdens of our times.

A version of this article was also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.

Teaser photo credit: Solar panel installation at an information center adjacent to Ögii Lake in rural Mongolia. By Chinneeb – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11142161