This blog is based on a paper given to the University of Hamburg’s “Unsustainable Past – Sustainable Futures?” conference on 12 February 2021. A video of the presentation is available.

In his foreword to our 2018 Breakthrough report on scientific reticence and the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC), Prof. Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, the Director Emeritus of the Potsdam Institute, wrote that:

“When the issue is the very survival of our civilisation… conventional means of analysis may become useless.”

And yes, he was talking about the IPCC! This failure of analysis extends beyond the science of climate change, to the political economy of climate disruption.

The climate policymaking orthodoxy is that markets can efficiently price and mitigate climate risks, but this blog argues that when risks are existential — that is, a permanent and drastic curtailing of human civilisation’s future development — then the damages are beyond calculation. What follows is that conventional climate cost-benefit analyses and climate-economy models, which rely on the quantification of both the potential damages and the probabilities, are of little value, and that markets cannot efficiently assess or optimally price the risk.

RISK

In cases of existential risk, markets fail because they can not adequately assess or respond to the risks. Nor can they mitigate the threat to society as a whole. This is true for weapons of mass destruction, for pandemics and ecological collapse, and for other existential risks, where the primary risk-management responsibility lies with the state apparatus. It is also true for climate disruption, where markets have failed to heed the high-end risks — especially non-linear impacts and system tipping points which are difficult to model — and where the range of potential second-order impacts is difficult to articulate.

Policies enacted as a result of Paris Agreement national emission-reduction commitments are likely to result in warming of around 3°C by 2100, and perhaps 4°C or more when all the feedbacks and system non-linearities are taken into account. 3°C of warming is described as “catastrophic”, and 4°C likely to be incompatible with the maintenance of human civilisation.

And yet, the global market’s response has been to grow emissions, year on year.

3-5°C of warming is clearly an existential threat to human civilisation. This prospect requires a fundamentally different approach to managing the risks, with a four-part strategy:

- Consider the full range of possibilities, and fully assess the lower probability, high-impact — or “fat-tail” — risks which may be devastating for human society;

- Apply the precautionary principle when faced with uncertain threats that may cause systemic ruin;

- Take a normative approach to managing risks, setting targets and developing strategy;

- Integrate responses across national and regional boundaries, recognising complexity cannot be treated in separate “silos”.

Neither the IPCC processes, nor those of the UNFCCC, do this. This is a fatal mistake.

Climate policy-makers accept as reasonable a 33% — or even a 50% — risk of failure, even when that failure equates with planetary-level systems disruption. An example of this are the risks of one-in-two or one-in-three chance of failure used in so-called “carbon budgets”, which are used to justify continuing high levels of emissions as “reasonable” for particular warming goals.

This is ethically indefensible. Who accepts even a 1% risk of failure when they cross a bridge or get into a lift? Why do policymakers and climate action advocates accept risks of failure when it comes to the planet that they would never accept in their own lives?

The IPCC assessment reports bear a large responsibility for underplaying climate risk, with their preference for conservative projections and scholarly reticence, and the downplaying of the most damaging possibilities.

PHYSICAL REALITIES

Prof. Schellnhuber also reminds us that “Political reality must be grounded in physical reality or it’s completely useless.” Here are five key understandings:

- Warming has already reached 1.2°C and is likely accelerating, with 1.5°C likely by 2030. The illusions of a carbon budget for keeping warming below 1.5°C, and an incremental, non-disruptive path for holding warming below 2°C are now fully exposed.

- At just 1.2°C of warming, climate disruption is already dangerous, with tipping points already passed for large-scale systems including coral reefs, Arctic sea-ice and West Antarctic glaciers. There is debate about whether the Amazon rainforest is also close to tipping, and strong evidence that before or around 1.5°C the Greenland ice sheet will reach its tipping threshold.

- Around 2030 and with warming at 1.5°C, there is a risk of blue-water Arctic summers as sea-ice extent collapses and regional warming is amplified to be three times the rate of the global average. The risk will grow substantially that Arctic carbon stores including permafrost and boreal forests will suffer substantial, accelerating and unstoppable carbon losses.

- If a prudent risk management approach is taken, the carbon budget for the 2°C target is zero.

- In 2018, scientists propose a “Hothouse Earth” scenario in which system feedbacks and their mutual interaction drive Earth’s climate to a “point of no return”, whereby further warming would become self-sustaining, without further human emissions. This threshold could exist at a temperature rise as low as 2°C, possibly even in the 1.5°C–2°C range. In a followup paper in 2019, they say that:

“The evidence from tipping points alone suggests that we are in a state of planetary emergency: both the risk and urgency of the situation are acute… If damaging tipping cascades can occur and a global tipping point cannot be ruled out, then this is an existential threat to civilization. No amount of economic cost–benefit analysis is going to help us… we might already have lost control of whether tipping happens.”

ACTIONS

Four key understandings flow from thse physical realities:

First, zero emissions fast. Even if the all-too-generous carbon budgets of the IPCC are accepted at face value, national carbon budgets for developed economies with high per capita emissions require annual decarbonisation rates of around 10% or more once global equity issues are accounted for. That’s zero emissions by or before 2030.

Advocacy in the developed economies of the currently fashionable “net zero emissions by 2050” is simply climate colonialism, implicitly claiming a right by the rich for higher ongoing per capita emission rates than people in the developing world. A 2050 timeframe will not prevent catastrophic outcomes, and such long-term targets have been an excuse for procrastination.

The short term is crucial; what we do now and before 2030 matters most. Former UK chief Scientist Prof. Sir David King, who has helped establish the Cambridge Centre for Climate Repair, says that: “What we do over the next 10 years will determine the future of humanity for the next 10,000 years”.

Second, drawdown. King says we have passed the point where we can simply say if we reduce emissions we will be fine. Mitigation is vital but will not have a noticeable beneficial impact on the temperature trajectory for two decades, due to concurrent aerosol loss.

King, like James Hansen and many others, emphasises the need to get the atmospheric concentration of greenhouses down from the present level of 415 ppm to well under 350 ppm and ideally under 325ppm, with a large-scale carbon drawdown programme to restore a safe climate (see for example, King’s presentation to the Matters of fact: The science of getting it right forum this year, starting around 41 mins; or this interview).

The Cambridge Centre prioritises: “The creation of new greenhouse gas (GHG) sinks which are scalable, inexpensive and safe, capable of removing hundreds of billions of tonnes of GHGs to return atmospheric concentrations to less than 350 ppm”. This is a massive and challenging task!

Third, planetary cooling must now be on the agenda. Scientists worry that Arctic dynamics and abrupt change, even this decade, have an unacceptable risk of starting to trigger the conditions for a Hothouse Earth scenario, with sea-ice-free summer conditions around 2030 driving further self-sustaining warming feedbacks – both due to changed reflectivity and mobilisation of frozen carbon stores. This could potentially be the trigger for humanity’s long descent into collapse.

Regional cooling of the Arctic is now crucial to mitigating the Hothouse Earth risk, says Sir David King. The Cambridge Centre emphasises “the development and assessment of approaches and technologies for refreezing the polar regions and restoring other damaged climate systems”, such as the Himalayas.

Zero emissions, even in a decade, coupled with large-scale drawdown, is not sufficient to negate the existential risk, hence all means of planetary cooling must be considered, whether that be solar radiation management or reflectivity proposals such as MEER. There is no evidence yet that solar radiation management, for example, has a net environmental and social benefit, but if that proves to be the case, it may be considered an interim cooling measure.

Fourth, adaptation. Managing the unavoidable climate risks and impacts should be seen as a parallel strategy to mitigation, which seeks to avoid the unmanageable risks, and should prioritise actions to protect the most vulnerable human populations and nature. But it is no substitute for deep climate mitigation and restoration because it is not possible for most people and nature to adapt to 3–5°C of warming this century, and there is the danger of the “adaptation trap”, where most effort is put into adaptation and the lack of adequate mitigation delivers a “hothouse Earth”.

MOBILISATION

These tasks — of reaching zero emissions as fast as possible combined with large-scale carbon drawdown from atmosphere — are enormous undertakings given the compressed time scale, and involve both the disruptive stranding of fossil fuel assets, and the remaking of much of our productive capacity and infrastructure. It would be the greatest planned peacetime transformation of the economy in history.

The generalised collapse of contemporary societies is not certain or inevitable. However, it is likely unless dramatic action makes climate the number one priority of economics and politics, with an audacious, planned transformation. In other words, a climate emergency response.

In a 2008 book written with Philip Sutton, Climate Code Red, we described a “normal political-paralysis mode”, in which:

- There is a lack of urgency;

- market needs dominate political responses;

- budgetary allocations are restrained ;

- socio-economic goals are determined by political trade-offs, compromise and systemic inertia.

By contrast, we described an emergency response as one in which:

- Immediate, or looming, threats to life, health, property, or environment are recognised;

- Speed of response is crucial with risk of threat becoming overwhelming

- The crisis is of the highest priority for the duration;

- Bipartisanship and effective leadership are generally the norm;

- All available/necessary resources are devoted to the emergency.

Societies that are successfully overcoming the Covid pandemic threat — in my own country of Australia, for example, where rates of community transmission are close to zero — are doing so with an explicitly emergency response that makes the threat the highest priority of politics and economics, based upon acceptance of the best available science.

In an emergency, the leading role in mobilising society is taken by the State: think of bushfires, floods, cyclones, for example. The more successful Covid emergency responses have included the early exercise of hard State power such as lockdowns — which have the effect of curtailing non-essential production — and restrictions on movement as were deemed necessary.

MARKETS

When bushfires or floods threaten people and property, we do not put out a tender to the market and price natural disasters as if they are a commodity. Instead, the state responds immediately because it is best positioned to prepare, plan, and act. This is necessary also for the climate emergency, because markets can neither adequately assess the risks nor mitigate the threat.

This is due to a number of interconnected factors, discussed below, drawing in particular on the work on “Radical Uncertainty” by economist John Kay and former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King, and “Finance, climate-change and radical uncertainty: Towards a precautionary approach to financial policy” by researchers from the University College London and the New Economics Foundation, led by Hugues Chenet.

Neo-classical economics assumes an idealised world of market participants operating with “perfect knowledge” to produce efficient prices and optimal outcomes, but Kay and King explains that we “live in a world of radical uncertainty in which our understanding of the present is imperfect, our understanding of the future even more limited, and in which no one person or organization can hold the range of information required to arrive at the ‘best explanation’.” When our world ends, they say, it will likely be “as a result of some contingency we have failed even to imagine”, so “good strategies for a radically uncertain world avoid the pretence of knowledge— the models and bogus quantifications which require users to make up things they do not know and could not know.”

Chenet et al. apply the radical uncertainty analysis to financial markets and conclude that:

“Climate-related financial risks (CRFR) both physical and transition risks – are subject to radical uncertainty and are not well suited to conventional ergodic and exogenous financial risk analysis, which makes the quest for accurate ‘measurement’ particularly difficult. Radical uncertainty prevents the generation of reliable (‘efficient’) prices and as such prevents financial system participants from having the deterministic or probabilistic vision of the future that they are looking for… Thus, the existing approach to CRFR is not fit for purpose. Scenarios and stress testing are useful tools in the face of uncertainty, but the quantitative modelling they rely upon cannot compensate for the ‘unknown unknowns’ attached to underlying socio-economic phenomena and mechanisms” (emphasis added).

Thus the factors that prevent markets from effectively dealing with climate risks include:

Climate change impacts cannot be fully captured by science at present: The physics of climate change is inherently complex because it describes the dynamics of a multi-dimensional, non-linear system, involving many subsystems and networks of adverse cascade effects. The current scientific approach is unable to capture all processes taking place (Chenet et al.). Whilst many of the basic and relatively linear physical processes are well known, climate models have no so far been able to well incorporate all the non-linear system interactions, such as permafrost carbon stores and polar ice sheets. In 2006, Richard Alley noted that his fellow scientists had expected ice sheets to gain mass through to 2100 (and the IPCC agreed), but recent events had showed that “We’re now 100 years ahead of schedule”. And when research was published in 2014 showing West Antarctic glaciers had passed their tipping points, Malte Meinshausen described the news as “a game changer, this is just one surprise with global warming of only 0.8 degrees of warming”, and a “tipping point that none of us thought would pass so quickly”, showing we are ”committed already to a change in coastlines that is unprecedented for us humans”.

The impacts of climate change are unquantifiable: In the social and economic domains of complex human global systems, second-order impacts — such as climate-enhanced armed conflict, state breakdown and mass migration — are radically uncertain; that is, probabilities cannot meaningfully be attached to alternative futures. Virtually no-one saw the war in Syria coming on the back of record-breaking droughts and populations displacement. Climate change is a “ruin” problem of irreversible harm with a risk of total failure, meaning negative outcomes are economically unquantifiable and may be infinite, and thus an existential threat to human civilisation. A recent IMF Working Paper notes a “growing agreement between economists and scientists that risk of catastrophic and irreversible disaster is rising, implying potentially infinite costs of unmitigated climate change, including, in the extreme, human extinction”.

Probabilistic risk analysis is not appropriate for assessing climate change impacts: Existential risk and unpredictable, non-linear processes mean climate change consequences cannot be adequately expressed by probabilistic analysis, which reduces complexity and high levels of uncertainty to numerical expressions and formulae. Schellnhuber describes a “probability obsession”, but says “calculating probabilities makes little sense in the most critical instances”, in part because “we are in a unique situation with no precise historic analogue”. Yet probabilistic analysis is at the heart of the theory that markets can price climate risks. Corporate and state climate plans and scenarios lack appropriate non-probabilistic risk-management approaches to both the physical and social risks, and exhibit an inadequate understanding of the high-end possibilities. Mostly, they are based on IPCC processes and methods, which are scientifically reticent and a poor basis for understanding the full range of potential outcomes.

Climate change risks are not well incorporated into economic models and cost-benefit analysis:

Most institutions lack the analytical tools for in-depth climate risk assessment, and rely on statistical and probabilistic modelling tools in assessing climate-economy interactions. Many typical climate-economy models haven’t incorporated thresholds, cascades, non-linearity, non stationarity, missing variables, high-level uncertainty and infinite damages, and are of very limited use. Unquantifiable potential damages severely limit the efficacy of cost-benefit analysis. Sir Nicholas Stern said of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report and its climate-economy models: “Essentially it reported on a body of literature that had systematically and grossly underestimated the risks [and costs] of unmanaged climate change.” and Prof. Kevin Anderson of the University of Manchester says there is “an endemic bias prevalent amongst many of those building emission scenarios to underplay the scale of the 2°C challenge. In several respects, the (climate-economy) modelling community is actually self-censoring its research (focus) to conform to the dominant political and economic paradigm… ”

Financial markets cannot efficiently assess/price climate-related risks: Climate-related financial risks are subject to uncertainty around both their severity and time frames and are not well suited to conventional risk management tools and indicators. Radical uncertainty prevents the generation of reliable (optimal/efficient) prices, undermining a probabilistic view of the future. Concomitant reactions between market players would likely lead to a network of adverse cascade effects (Chenet et al.), constituting a systemic risk to the financial system as a whole. Climate is not a market optimisation problem, it’s a risk problem — the risk of the loss of capitalism — says financial analyst Spencer Glendon. He also notes that “The economics of climate change will be seen as one of the worst mistakes humans have made”, overlooking consequences including mass migration and state breakdown which are beyond economic models and market calculations.

Sensible risk management demands a precautionary approach: Climate policymaking is informed by middle-of-the road analysis of risks. The systemic magnitude and irreversibility of the threats, and the existential risks, demands a precautionary approach, emphasising the high-end possibilities, not the probabilities, by asking the question: “What is the worse thing than could feasibly occur, and what do we have to do to prevent it?”. This is very different from conventional risk management that is currently applied to climate risk; something markets are very poorly equipped to handle. Chenet et al. emphasise that a precautionary approach is suited to “ruin” problems, in which a system is at risk of total failure; with such problems, “what appear to be small and reasonable risks accumulate inevitably to certain irreversible harm”.

Thus the climate problem won’t be solved by capital markets: markets require system stability, but we are now in an era of system-level instability: in the finance sector, in the physical world, and in politics. We now face large-scale climate disruption: either planned by way of a fast, emergency transition to restore a safe climate, or much worse unplanned chaos because non-linear physical change, and socio-economic system failure, will inevitably occur as warming intensifies. Gradualist solutions that assume time is on our side are not relevant.

In a powerful essay, The Last Hurrah, Alex Steffen describes Biden’s ambitious climate plans: as a “knot in the heart of American climate policy, even today: what many Americans consider unreasonably radical changes are not actually bold enough in the face of the climate emergency… it feels like it’s fast, because it is; it feels like it falls short, because it does. It’s not enough. We’re still winning far too slowly to celebrate.”.

Steffen says his gut feeling is that “what this administration is proposing is probably close to the limit of what’s possible in 2021 in American politics”, but is far from enough.

“We have run on for a long time, living in (often willful) blindness, telling ourselves comforting stories of continuity and gentle transitions, but sooner or later the fierce realities of life on Earth were always going to catch us. They’re very close now. That’s their breath you feel, raising the hairs on the back of your neck,” he says.

CHALLENGES

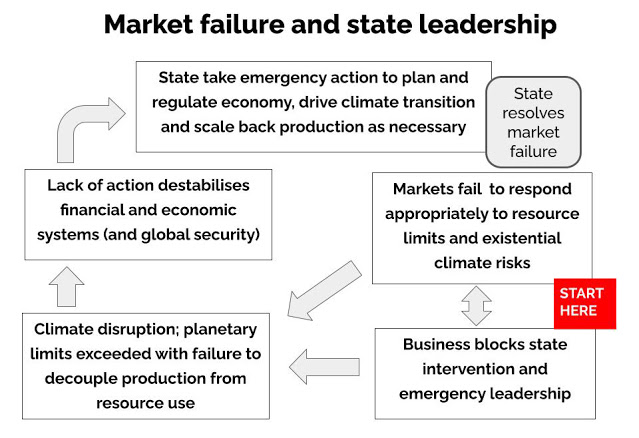

The problem is exacerbated by the failure so far to decouple resource use from consumption, as well as carbon pollution from production. Business has consistently blocked the required state-level intervention and leadership. Inflamed by the fuel of financialisation which triggered the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the lack of action on planetary limits, including resource depletion and climate disruption, will destabilise financial markets and global security.

Climate is in the end not a market optimisation problem, says financial analyst Spencer Glendon, but a risk problem: the risk of capitalism’s collapse.

At this point the State — capable of delivering fast, disruptive change — will be forced to respond to systemic exceedance of planetary limits and market failure, take emergency action, redirect current economic behaviour to socially useful ends and scale back production as necessary (see diagram).

If investors don’t change direction now, then at some later, far-too-late point, then government — through decarbonization and other regulatory efforts — will likely “have to pull that lever hard, and I think that would cause a lot of massive, massive disruption,” says Dickon Pinner, a senior partner at McKinsey. Pinner adds that the global economy relies on endless layers of systems that were built within the stable climate of the past, but “investing in an environment where tomorrow doesn’t look like today is very tricky”.

And governments do have that power. Former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis says one lesson from the 2020 pandemic response is that “governments had been choosing not to exercise their enormous powers so that those whom globalization had enriched could exercise their own”.

In the current low-growth period, decarbonisation and decoupling costs cannot be absorbed by growth, but only by re-allocation. Add in equity issues within and between nations, and the lack of a credible scenario to provide nine billion people with reasonable living standards, there is no choice but to reduce excessive consumption and emissions of the richest 20% of the global population.

If proposals focussed on Green New Deals and market-driven growth fail to deal with systematic market failure on climate risks and resource depletion, so also enhanced social expenditure will also fail if State leadership does not provide a path out of the climate and ecological crises via emergency policies.

Degrowth is necessary in the absence of absolute decoupling, but the degrowth movement has yet to produce even a basic strategy on how its objectives can be translated into institutional structures at State or global level, especially within the 2030 timeframe.

The situation is unprecedented. Emergency-level action will become inevitable, but will it be democratic? Reducing the hyper-consumption of the world’s most affluent sector seems like an unimaginable political obstacle, says Boris Frankel. People do not lightly take to deep change, even when it is necessary to protect the things they care about. Frankel asks whether preventing ecological and civilisational disaster is more important than democracy, especially as the “conflicted state” is wedged between the need to transition to a sustainable economy operating within safe planetary boundaries, and business and community opposition to the actions that are required to achieve it.

Clearly public education and mass public mobilisations are a key, pressuring State institutions to implement emergency measures. But movements such as Extinction Rebellion will fail if proposed ‘citizen’s assemblies’ become mere talking shops devoid of any clear and urgent set of proposed State actions.

Business has so far failed to take the challenge seriously enough, perhaps even to understand its full measure. Neoliberalism has served it well, and strong strong state intervention is anathema. Capitalist dynamics have been and are incapable of responding appropriately, as we have seen, given the failure of markets to deal with the real risks. Change would require longer-term interests and the “common good” be placed above short-term interests that presently dominate the market.

Most of the global capitalist elite, by their actions, indicate that they think they can survive well enough despite disabling climate impacts. According to Bruno Latour, most of the ruling class recognises that in a hotter world there will not be enough Earth for everyone, hence they have given up on a common future purpose for humanity. In their world, says Latour, AI and automation will replace the shrinking global population, with elaborate plans for self-protection such as escape to a New Zealand hideaway as plan B; or heading for Mars as plan C, led by Musk, Branson and Bezos.

Three critical features of our time are climate denial and delay, deregulation and growing inequality, says Latour. They have helped create a super-rich caste, who are determined that a sort of “gilded fortress” must be built for that small percentage who would be able to make it through. Now that fortress is pure fantasy:

- Firstly, it grossly underestimates the physical impacts of climate change, the aridification, unliveable heat, sea-level rise up to tens of metres, chronic water shortages, ecological implosion, and so on. Techno-optimism has blinded capitalist elites.

- Secondly, it underestimates the social consequences. At just 3°C, for example, perhaps a billion people will be displaced globally and coastal cities inundated, contributing to a chronic breakdown in production and supply chains, political mayhem and what US security analyses describe as likely to be outright global chaos.

- Thirdly, in such circumstances, the global market and financial systems, which are already fragile and destabilised, will collapse. And with it the illusion of a gilded fortress will crumble.

If this scenario is to change, the ruling elites — more or less as they exist now — must be part of the transformation, given the imperatives for dramatic action on a short, decadal time-frame. What, if anything, could bring them to their senses?

How can their vehement opposition to state leadership on sustainability and the climate emergency and a common future purpose for humanity be broken? Can a sustained mobilisation of people who cherish this Earth and yearn for a future for humanity overcome this resistance?

On these questions hang the future of human civilisation.

Teaser photo credit: Photo by Linus Nylund on Unsplash