Open letter to FWS, sent directly to FWS employees on February 7, 2018.

Friends, colleagues, and past FWS co-workers,

I once considered the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to be the world leader in conservation, and was proud to sign on! But that was a long time ago: 1999 to be precise. Today, something is awry at FWS headquarters, and that’s what drove me to retire on October 31. Within the leadership ranks of the National Wildlife Refuge System, especially, ethical lapses have led to corrupt tendencies. The mission has suffered and careers have been impacted; none more than mine, which was perennially crippled by gag orders.

The prohibited topic? The trade-off between economic growth and wildlife conservation, also known as the “800-pound gorilla.” The trade-off was the focus of my Ph.D. research in the 1990’s, when I documented the causes of species endangerment as a who’s who of the American economy. I presented these causes in Science, elaborated in Bioscience, and detailed the sociopolitical context in a book on the Endangered Species Act.

The gag orders were ironic, because my background on the 800-pound gorilla was one of the reasons FWS hired me to begin with. As the first “conservation biologist” for the National Wildlife Refuge System, I was told to “think big,” “long term,” and “outside the box.” Beginning in 2001, though, I was strung along by Refuge System chiefs who said “It has to be talked about, but now is not the time.” I waited patiently for the right time to come, occasionally re-testing the waters and invariably getting re-gagged.

While the gag orders started in 2001, the harshest one was issued in 2011 while a previous director awaited his Senate confirmation hearings. I was prohibited from saying “anything having to do with economics.” Another ham-handed order was issued in 2016 as the presidential primaries heated up. All the orders – along with reprimands, suspensions, and various other forms of coercion – were designed to buffer appointees, chiefs, and deputies who were petrified by the politics of economic growth. Such abject fear belied the talents of one appointee who boasted, “I can drink politics with a firehose.”

Not all FWS or DOI programs are inclined to evade the topic. Rather, a clique of Refuge System chiefs has squashed every reasonable effort to raise public awareness of the trade-off between growth and conservation. Now we are paying for this lack of awareness across the landscape.

Lest anyone think the gag orders reflected a technical disagreement, I quote a long-time Refuge System chief: “Everybody knows there’s a conflict between economic growth and wildlife conservation. It’s just not our role to talk about it.” Thankfully such shirking doesn’t infect every agency. Imagine the Surgeon General acquiescing, “Everybody knows smoking causes cancer. It’s just not our role to talk about it.”

Furthermore, the chief was off-base with “everybody knows,” unless he considered “everybody” to be FWS, where we’ve all witnessed the growing economy usurping, eroding, or polluting habitats. He failed to acknowledge the widespread misinformation outside FWS. Politicians, seeking to appease, mislead the public with, “There is no conflict between growing the economy and protecting the environment.”

The gag orders weren’t politically affiliated, either. The win-win rhetoric of “no conflict” was common to Democratic and Republican administrations alike. It was patently false in a bipartisan way, “everybody knew it” (at least in FWS), and sound science had refuted it. Yet to this day the win-win rhetoric constantly re-appears in public forums from the local town hall to the halls of Congress. It attracts wishful followers of all kinds, enough of them to keep economic growth atop the pedestal of domestic policy.

If the gag orders stemmed from neither technical disagreement nor political fealty, then why were they issued? In my opinion the answer is an indictment of an agency gone astray.

Corruption isn’t always as cut and dried as, for example, nepotism or embezzlement. For 18 years I watched chiefs come and go at headquarters, and in recent years especially, the layers of chiefs have treated the Refuge System as their oyster, incessantly travelling to spectacular refuges, rendezvousing regularly at the National Conservation Training Center, and even jaunting overseas to “assist” foreign nations. Their travelogues would be the envy of National Geographic explorers (with lulls only at times of intense political scrutiny). These chiefs are unwilling to jeopardize their tax-paid perks on a heavy topic at the heart of conservation. Maybe it’s not corruption per se, but it’s certainly unethical, unsustainable, and irresponsible.

Our privileged chiefs need a reminder of what it means to be a leader. Theodore Roosevelt said, “Nothing in the world is worth having or worth doing unless it means effort, pain, and difficulty.” He didn’t mean the “effort” of airline travel, the “pain” of per diem paperwork, or the “difficulty” in skirting a challenge. In FWS, leadership at the national level means identifying the biggest challenges to wildlife conservation, then mustering the fortitude to address precisely those challenges.

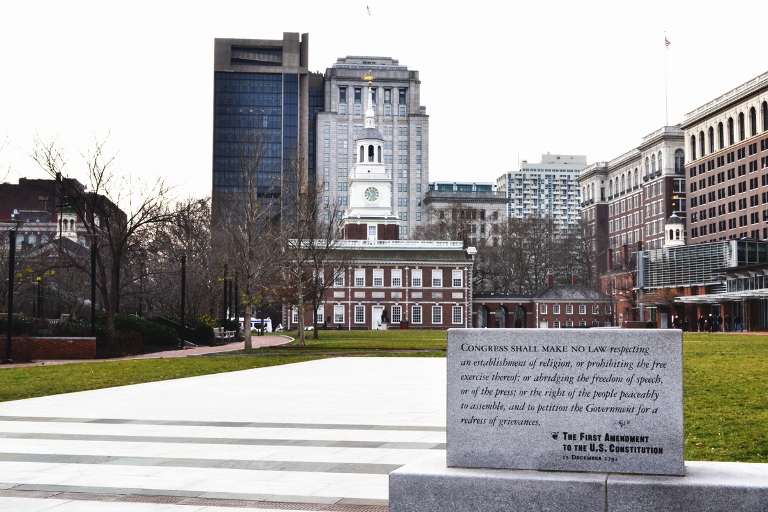

In retrospect, after studying the relevant case law (Pickering v. Board of Education, Garcetti v. Ceballos, etc.) and speaking with First Amendment experts (including Ceballos), I am convinced my gag orders would have failed the test of constitutional jurisprudence. I only wish I’d had enough time left in my FWS career to challenge the gag orders in court, for I surely would have. Alas, I ran out of time as my next job beckoned.

But you might have the time! Pursuant to your First Amendment rights as private citizens who happen to work for the government, don’t allow anyone at FWS or DOI prohibit you from raising awareness of the trade-off between economic growth and wildlife conservation. As a private citizen, you do have the rightto speak on issues of public concern, even in the workplace.

At the very least, you can talk about the 800-pound gorilla on lunch and coffee breaks: that’s First Amendment 101. But your rights are far greater. Most of you can broach the topic as part of your duties, as context for your program, or in many other creative venues such as DOI’s electronic “ideas box.” The idea is to get the topic flowing enough to reach an audience of critical mass. An example of a productive pathway would be: Your program → division chief → AD → Director → Secretary of the Interior → Cabinet/President. Yet the possibilities for participants in this dialog are endless: other FWS programs, other government agencies, non-profit organizations, professional scientific societies, Congressional committees and caucuses, to cite the most obvious examples.

Who’s to say these conversations won’t reach the Federal Reserve as it debates monetary policy, or the Council of Economic Advisors as it advises the president on fiscal policy? Even beleaguered by all the gag orders, I managed to meet with one of the Council of Economic Advisors, talk with heads of state at Rio+20, and address the UN General Assembly in New York (albeit on my own time). Imagine what a well-primed political appointee could do! But it’s up to you to do the priming.

The fact is, you never know when one of our fellow discussants might be in a position to affect the rate of GDP growth and change the national dialog. It wasn’t long ago when a U.S. Treasury Secretary (Henry Paulson) was a big-time birder serving on the board of The Nature Conservancy, having grown up on a farm in Illinois. I believe he could have been a game changer in the growth debate, but he needed more information from the experts (you!) on the trade-off between economic growth and biodiversity conservation. His business education didn’t suffice. Without our insights and input, he was hamstrung by the win-win rhetoric, conceptually and politically.

So let us challenge any gag orders on the topic. If you happen to get one, be sure to call me. I’ll do my best to help you. Better yet, call PEER (Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility). They’re the best in the business at protecting federal employees from unlawful or inappropriate censorship.

And don’t let anyone tell you it’s just talk, that we can’t actually do anything about it. That’s the logic of simpletons and cynics. Let’s face it, in government we don’t do anything without talking about it. And to some degree, that’s the way it should be. You don’t just adopt a new policy, budget, or interest rate hike without a thorough dialog about the consequences, good and bad. Yet, in direct contradiction to the goal of wildlife conservation, we have allowed economic growth to be treated as an unquestioned goal, to be pursued forever with no questions asked.

In the halls of FWS, I believe the topic of economic growth will once again spur rational, insightful, and courageous conversations. These conversations should occur at national wildlife refuges, ecological services offices, fish hatcheries, and especially in regional offices and headquarters. As the limiting factor for wildlife in the aggregate, economic growth should be the unifying issue for wildlife conservationists at all levels and in all locales.

Economic growth is also a highly relevant issue at every societal level from local to national. Local discussions happen “where the rubber meets the road.” Community officials make local growth decisions. At the other end of the spectrum, national-level discussions are needed for influencing the fiscal policies of Congress and the monetary levers of the Federal Reserve. Headquarters staff getting paid the big bucks ought to be doing their part to spur these discussions.

Obviously you can’t go straight to the top. Hallway discussions are a modest start. That’s fine, because these discussions gradually permeate conference rooms, telephone lines, and the internet as well as reports, programs, and strategies.

As you talk about economic growth, you’ll discover it’s not the Holy Grail after all. Breaking it down to increasing population and per capita consumption – as measured by GDP – demystifies it and helps us recognize the inevitable impacts on wildlife. Thinking of the economy as integrated sectors – agriculture, extraction, manufacturing, and services – explains the geography of endangered species.

As the implications of this discussion come into focus, policy makers and consumers can take it from there. Once the discussion is widespread and thorough, policy makers will be less prone to pulling out all the stops for growth, while citizens will temper their consumption. The bulldozer will slow and younger generations will be encouraged to keep fighting for conservation.

Don’t think it’s impossible, either. Look no further than Europe, where a “de-growth” movement is afoot, making a difference already in many local scenarios. If they can handle the 800-pound gorilla, so can we.

I wish you the best. Maybe we’ll talk, but more importantly, hopefully you’ll talk, in particular about the fundamental conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation. The mission of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service depends upon it.

Sincerely,

Brian Czech, President

Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy

www.steadystate.org

brianczech@steadystate.org

@SteadyStateEcon

#GDPupNATUREdown

Teaser photo credit: By Robin klein – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24250149