The sight of Trump being charged in the US, and Johnson choosing to disgrace himself in the UK before a House of Commons Committee did it for him, all within a 24 hour news cycle, was almost too good to be true. Especially since the two men had been touring together recently, perhaps exchanging tips and tricks.

Maybe God is a wannabe scriptwriter, even if this was probably an early draft.

Given that both men got to benefit so richly from populism’s breaking wave in 2016, the timing also has something about it, as if the seven year periods that crop up in myth and folklore have a real meaning to them.

Notorious narcissists

But that’s not what I want to write about here. Both Trump and Johnson are notorious narcissists, and I am wondering what it is about our current politics that means that the qualities of narcissism are so rewarded by the electorate.

Since this is a long post, let me pull the threads of the story together before I get into the detail:

- There has been an increase in narcissism in Western societies over several decades, which seems to be linked to greater individualism;

- narcissists (especially grandiose narcissists) are more likely to be selected as leaders—in business at least—because they look like leaders, and then wreck the organisations they lead;

- narcissists are more likely to be involved in political activity than non-narcissists, and also less likely to value democracy;

- But it is still not clear whether this is a continuing trend or one that has passed its peak.

Self-esteem

The first thing to say is that narcissism is the shadow side of self-esteem, and generally we think of self-esteem as being a good thing. One 2018 paper notes that “the endorsement rate” among adolescents of the statement “I am an important person” climbed from 12% in 1963 to 77-80% in 1992.

Self-esteem is also increasing in the Western world:

Middle school students from the United States had markedly higher self-esteem scores in the mid-2000s compared with the late 1980s.

So it’s probably worth separating out the two at the start:

Narcissism and high self-esteem both include positive self-evaluations, but the entitlement, exploitation, sense of superiority, and negative evaluation of others that are associated with narcissism are not necessarily observed in individuals with high self-esteem.

Personal superiority and entitlement

There’s also a distinction in the literature between ’grandiose’ and ‘vulnerable’ narcissism. The two overlap. ‘Vulnerable’ tends to be associated with a “characterized by anxiety, a fragile self-concept, and low self-esteem“. Grandiose, in contrast, is

a more assertive and extraverted form characterized by high self-esteem, a sense of personal superiority and entitlement, overconfidence, a willingness to exploit others for self-gain, and hostility and aggression when challenged.

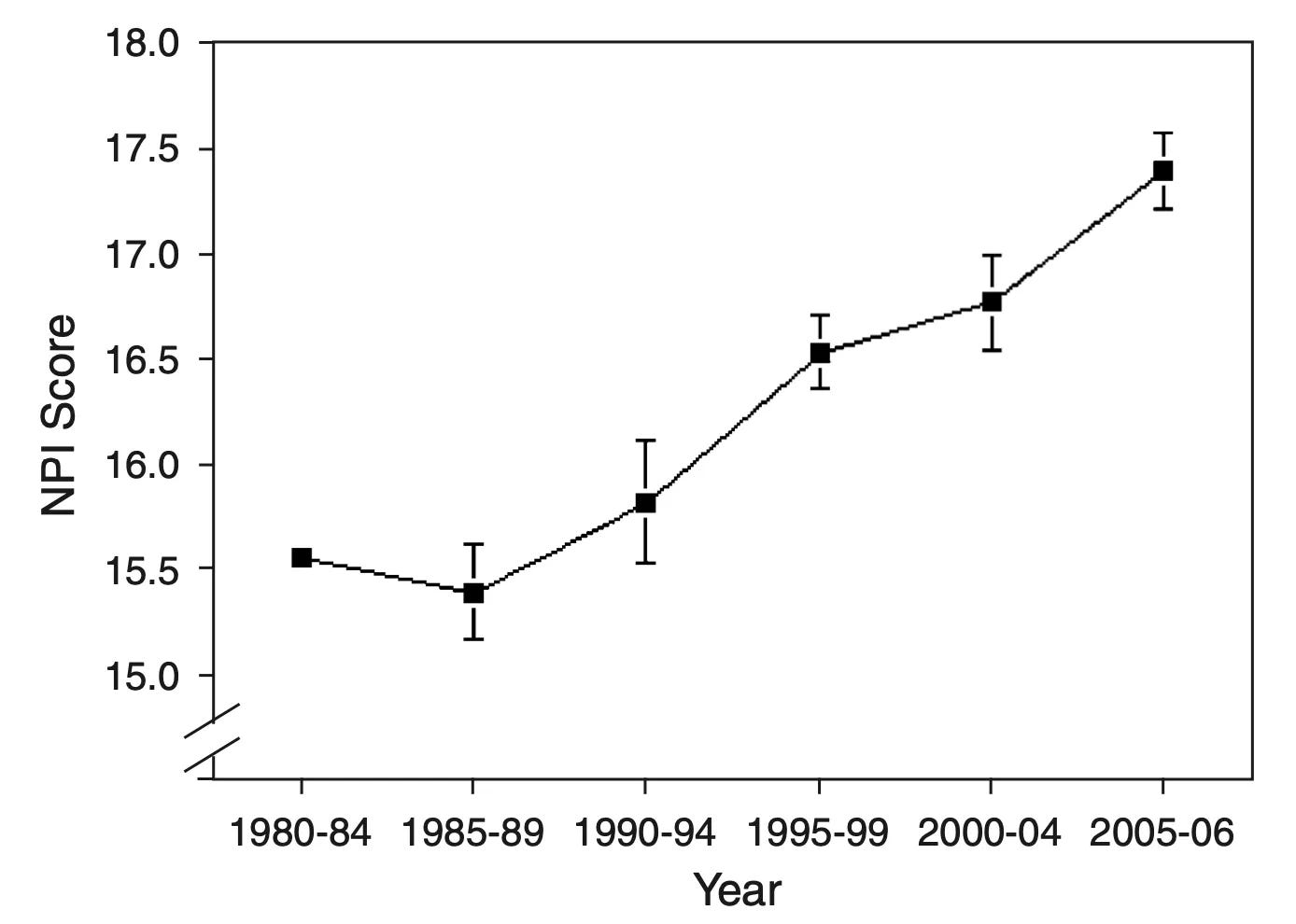

There are also measures of narcissism in the literature, assessed in the US by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory NPI), which measures for “self-reported grandiose narcissism” and this shows a 30% increase in grandiose narcissism between 1979 and 2006.

There are some problems with the NPI, but this finding seems to be borne out by other measures. And in terms of politics and business, we’re more interested in grandiose narcissism than vulnerable narcissism (although Trump appears to lurch between both).

Impulsive and over-confident

The psychology literature is generally more interested in all of this at the level of social effects. The business literature is more interested in leaders and their effects. A paper from Charles O’Reilly and Nicholas Hall more or less summarises these in its title:

Grandiose narcissists and decision making: Impulsive, overconfident, and skeptical of experts–but seldom in doubt.

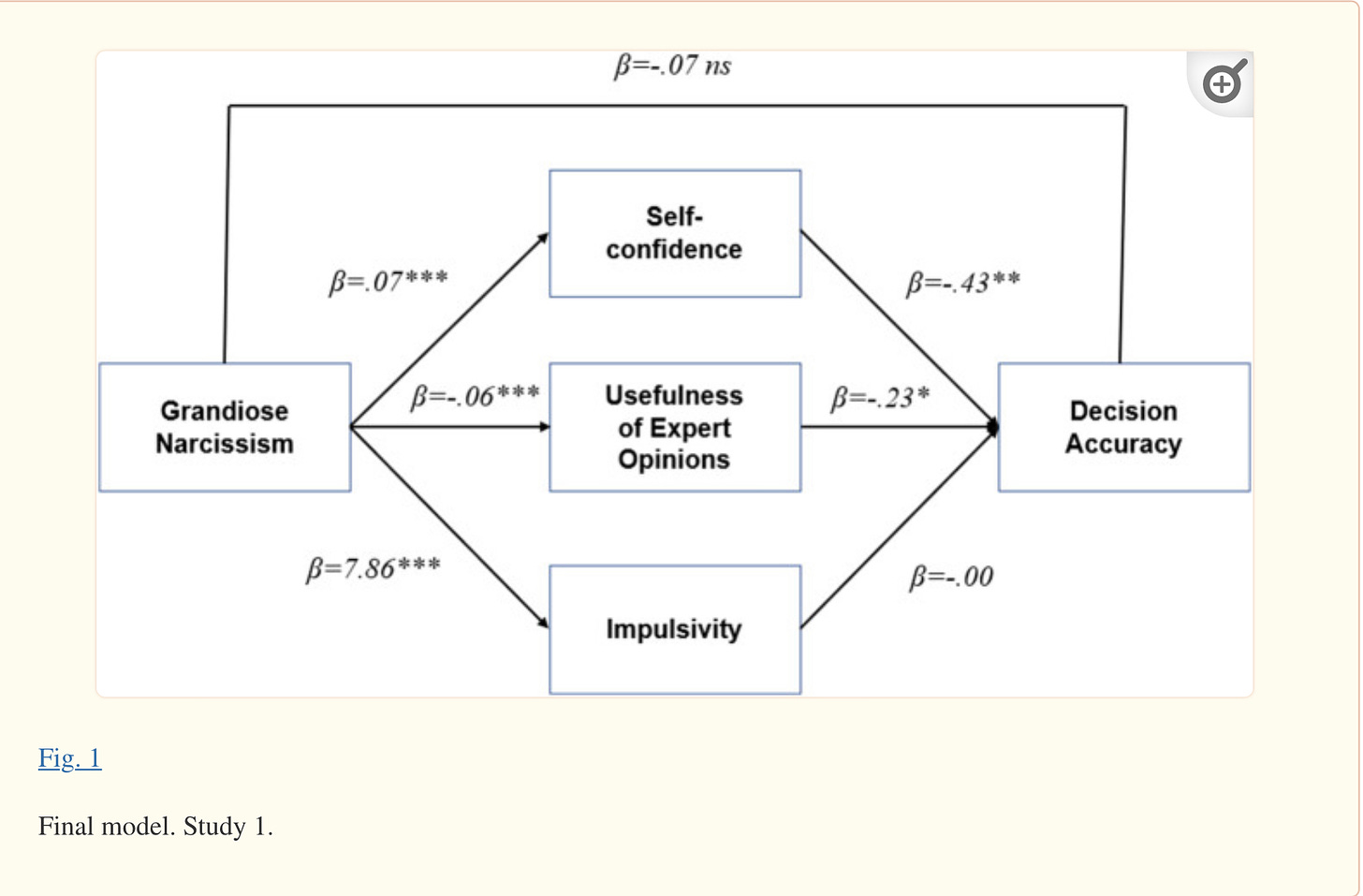

The article explores these three characteristics in more detail, by testing a set of hypotheses about the behaviour involved. The results of this model leads to a diagram that is also summarised in the text:

(Source: O’Reilly and Hall, 2021)

These attributes, which, in part, define grandiose narcissism, were, in turn, associated with the probability of making a poor decision (Fig. 1 ). Respondents who were more confident and saw experts as less useful were also more likely than those lower on these dimensions to make an incorrect choice. It was not narcissism per se that led to the increased probability of making an incorrect choice but the effects of narcissism on how respondents accessed information. Having made an incorrect decision, narcissists were also shown to be more likely to externalize the blame for their decision and to remain confident even after having made an incorrect choice.

Riskier decisions

It goes beyond “incorrect choice”, however, to a whole leadership style:

(O)nce in positions of authority, grandiose narcissists have also been found to make riskier decisions and jeopardize their institutions (O’Reilly & Chatman, 2020)… These tendencies make them potentially dangerous as leaders when their decisions can affect the lives and livelihoods of others.

An article at Stanford Business by Lee Simmons, which draws more widely on O’Reilly’s work, argues that one of the reasons why ‘grandiose narcissists’ are able to get into leadership positions is because they look like the type of people associated with leadership in modern organisations, notably because of their (over) confidence and willingness to be decisive. But—and of course there’s a but:

“They believe they’re superior and thus not subject to the same rules and norms. Studies show they’re more likely to act dishonestly to achieve their ends. They know they’re lying, and it doesn’t bother them. They don’t feel shame.” They are also often reckless in the pursuit of glory — sometimes successfully, but often with dire consequences.

Times of turmoil

All the same, O’Reilly and Chatman paper referenced above also makes a distinction between “abusive jerks” and “grandiose narcissists”. The former might still have a vision of the future that extends beyond themselves and so isn’t purely self-serving (think: Steve Jobs).

It seems that venture capitalists, in particular, are prone to choosing grandiose narcissists as leaders, which suddenly casts an insight into some of the behaviours of Silicon Valley start-ups over the years. And there are studies that show that when groups are set tasks in experimental settings, they are more likely to choose the grandiose narcissists in their ranks as leaders.

This last observation links to a clue about the circumstances in which such leaders emerge, again from the Lee Simmonds article:

O’Reilly thinks we may especially tend to choose narcissistic leaders in times of turmoil. “In the last few decades, big companies like automakers and banks have been threatened by technological disruption. So you could imagine that in anxious times people are looking for a hero, a confident person who says, ‘I have a solution.’” They may be the only ones who are confident in such times.

Grabbing power

Anxious times. In a slightly sprawling piece in Unherd, Tom McTague reminds us that the ‘end of history’ decade following the collapse of the Soviet Union was supposed to be about the end of ideology and the rise of managerialism. But that wasn’t how it turned out:

Yet this world gave us the Iraq war, the 2008 financial crisis, the implosion of the Arab world, mass, unexpected immigration, austerity and eventually Brexit. After 2016, Johnson rose to prominence mocking the egos of the establishment that presided over this mess, eventually grabbing power at the height of its failure. His opportunity came because of the failures of the political class at home and abroad.

Of course, Johnson contributed to making this chaos worse, when he plumped for Brexit. But Brexit, certainly, was the classic narcissist’s ‘solution’.

(‘Narcissus’, by Caravaggio. Circa 1594-96. Rijksmuseum. Public domain)

Beyond leaders

But this extends beyond leaders into politics more generally.

A 2020 study by in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin found that people with narcissistic personality traits were more likely to to be involved in politics. The study was conducted by Pete Hatemi and Zoltan Fasekas, and was based on existing survey data from the United States and Denmark:

(T)he surveys assessed narcissism and eight types of political participation: signing a petition, boycotting or buying products for political reasons, participating in a demonstration, attending political meetings, contacting politicians, donating money, contacting the media, and taking part in political forums and discussion groups.

More involved

In general there was little difference between non-narcissists and narcissists when it came to voting, but for all of the rest of political activity, narcissists were more involved. They are more likely to contact politicians, to sign petitions, to donate money, and, in the US, to vote in the slightly lower profile mid-term elections.

“The general picture is that individuals who believe in themselves, and believe that they are better than others, engage in the political process more,” the researchers wrote in their study. “At the same time, those individuals who are more self-sufficient are also less likely to take part in the political process. This means that policies and electoral outcomes could increasingly be guided by those who both want more, but give less.”

In an interview, Hatemi also noted the role of social media in amplifying certain types of behaviour:

“It is hard not to notice how much more of ‘me’ is part of our world — projecting one’s status at the cost of others, whether using social media such as Facebook or Instagram or Twitter. Gone are the days when children’s goals were to be something or do something important, replaced by the desire to be famous.

(‘Narcissus and Echo’, by David Revoy. 2006. CC BY 4.0)

Entitled and superior

It gets a bit worse than this. In terms of politics, people with a more narcissistic self-view are less likely to support the idea of democracy. (There’s only a summary of this research in front of the journal paywall). Researchers at the University of Kent and the Polish Academy of Sciences (in a 2018 paper) built on previous research that found that basic personality traits could predict individual opinions about the social world. Their research was in Poland and the United States. The summary describes the rationale in this way:

(T)his is probably because narcissists tend to feel entitled and superior to others, which results in lower tolerance of diverse political opinions. In contrast, people who take a positive, non-defensive self-view and trust others are more likely to show support for democracy, the research found.

‘Collective narcissism’

This seems to link to a 2019 paper in in Political Psychology. by Polish researchers in Poland and London, on the idea of “collective narcissism”. From the abstract, collective narcissism is

the belief that the ingroup’s exceptionality is not sufficiently appreciated by others. Collective narcissism is motivated by the investment of an undermined sense of self-esteem into the belief in the ingroup’s entitlement to privilege. Collective narcissism lies in the heart of populist rhetoric. The belief in ingroup’s exceptionality compensates the undermined sense of self-worth, leaving collective narcissists hypervigilant to signs of threat to the ingroup’s position. People endorsing the collective narcissistic belief are prone to biased perceptions of intergroup situations and to conspiratorial thinking. They retaliate to imagined provocations against the ingroup but sometimes overlook real threats. They are prejudiced and hostile.

The thing of this, of course, is that the notion that one’s sense of self-worth is being undermined might not just be a pathology. It can also be a product of the material conditions that you find yourself in. Sometimes, the cat has actually pissed on the couch.

Objects to be used

The combination of globalisation and technology, and the politics and economics of how these were managed, spread out a lot of losers while also funnelling the gains into a smaller number of winners. Equally, the political economy of the ‘Third Way’, and other convenient political fictions, emphasised the market in the provision of public goods such as health and education. As Marianne Fotaki wrote in a prescient (2014) piece on the LSE blog:

Susan Long has persuasively argued that whole societies may be caught in a state of pathological perversion whenever instrumentality overrides relationality – that is, whenever narcissism becomes dominant, other people (or the whole groups of other people) are seen not as others, like oneself, but as objects to be used. For instance, when markets are seen as anonymous ‘virtual’ structures, employees may be seen and treated as exploitable commodities. Such behaviours are pathologically perverse in that people disavow their knowledge of the situations they create through narcissistic processes.

We can take this further, I think. The role of businesses and business leaders in sponsoring narcissistic leaders and supporting policies that increased the transactional nature of society and of work has amplified the sense of drift and lack of esteem felt by individuals in societies.

In retreat

Academics being academics, most of these researchers don’t offer prognoses of what might happen next. When they do, they are pessimistic. But it is certainly possible to speculate that some of the trends that made possible the politics of narcissism are in retreat.

One of the effects of the populist crisis has been to make politicians more aware of the losers from globalisation, even if they still sometimes seem to find it hard to do that much about it. Facebook, certainly, is in something of a decline, as its user base ages.

Some of the values of Millennials seem quite individualist to me (though less so than Boomers and GenX), and in workplace settings they are less likely to put up with the behaviours of narcissistic leaders. GenZ seems more interested in self-esteem and less in narcissism, which is one of the things I took away from John Higgs’ book The Future Starts Here. His take on the GenZ worldview:

It is only when everyone accepts how everyone else defines themselves that the world can be trusted to allow you to be yourself.

Data sets

All the same, certainly in the US, the politics of grievance both going strong and is actively fuelled by the Republican Party. And Vladimir Putin, of course, shows every sign of grandiose narcissism without any checks or balances, at least this side of the International Criminal Court.

At the beginning of this post, I summarised research that suggested that narcissism was on the increase. Most of the data sets seemed to end a decade or more ago. The investor Joachim Clement picked up on this point in a post on narcissism he wrote earlier this year. Here’s data from research from Jean Twenge published in 2008 on the prevalence of narcissism in US college students.

(Source: Jean Twenge et al, 2008).

Formative years

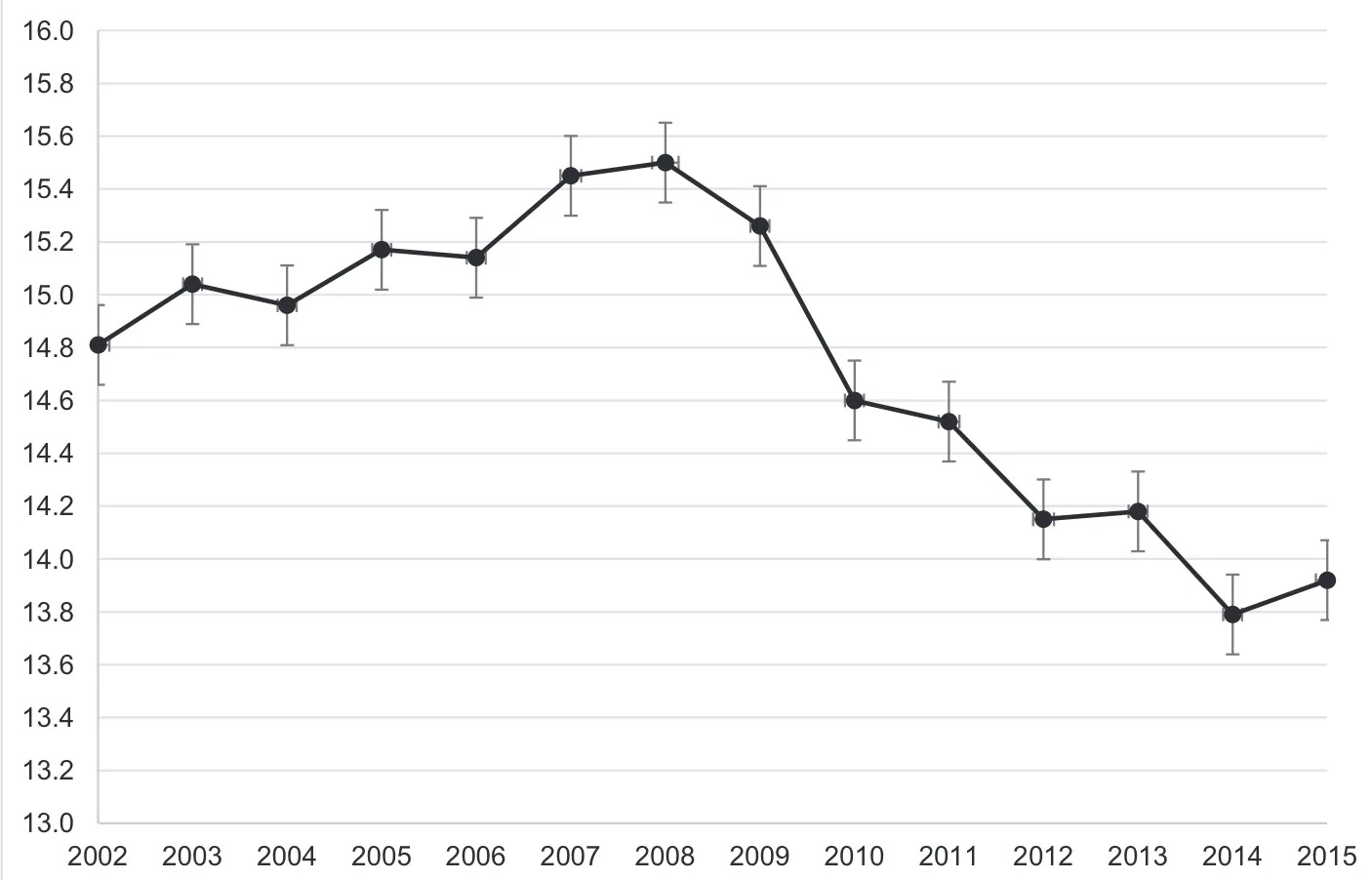

Klement observes that your worldview tends to be influenced strongly by what happens in your formative years (18-25):

(P)eople who experience tough times during their formative years act less selfishly and are more interested in the common good than people who experience good times. In other words, people who have been in their formative years during and after the global financial crisis should score lower on the narcissism scale than previous generations.

So he’s interested in the data on the level of narcissism among after 2008. And 2021 data on US college students, also published by Jean Twenge, which continues the sequence through the Crash, supports this hypothesis:

(Source: Jean Twenge et al, 2021)

So it is possible to suggest—in the spirit of a weak hypothesis, lightly held—that the great wave of narcissism-driven populism that dominated the 2010s, is beginning to recede. Of course, this isn’t much of a consolation. Grandiose narcissists wreck everything they touch, and there is a trail of debris behind them that will take years to clear up.

—-

A version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.