There was a demonstration in Oxford (England) last weekend on the city’s proposals to implement a number of low traffic areas, but the demonstration was about more than that.

The climate journalist Dave Vetter covered the march, and shared a photograph of some of the flags and banners:

I’m live at the pro-traffic rally in Oxford city centre. Ostensibly a protest against LTNs, or low-traffic neighborhoods, it’s an intoxicating mix of far-right conspiracy slogans, antisemitism and really terrible hip-hop. pic.twitter.com/hfvCqm0OHT

— Dave Vetter (@davidrvetter) February 18, 2023

Tom Seward, a reporter on the Oxford Mail, was also there. More tellingly, perhaps, he shared a photograph of the leaflets that the protesters handed out during the march.

One of the leaflets being handed to the crowd. @TheOxfordMail pic.twitter.com/FitrR6LhsE

— Tom Seaward (@t_seaward) February 18, 2023

Normally, protestors against low traffic neighbourhoods are affluent locals with an over-developed sense of entitlement and a refusal to understand that traffic doesn’t actually work according to their ‘common-sense’ view of how it works. (Traffic isn’t water).

Worldviews

These protesters aren’t those protestors. It’s worth listing out the things on this leaflet, because they constitute a worldview, even if it’s not a worldview that’s immediately accessible to those who don’t share it.

- Sex Education in Primary Schools? A dangerous form of indoctrination?

- Why is the Price of Petrol So High? Additional 23% fuel tax rise planned by the UK Government April 2023

- Geoengineering Why? Weather manipulation & long-term outcomes

- Why Did the 1% Get Richer During 2020? The ten richest men doubled their fortunes

- UK Cost of Living Crisis? As the rich get richer, the rest of us are paying more?

- Why is The News Not on The News? Can we trust the media?

- What is the World Economic Forum? Why are so many politicians involved in the WEF?

- Cashless Society? What are the Risks? Who are we excluding in society by removing cash?

- The Global Pandemic of Trafficked Children. Why is this not headline news?

- Electromagnetic Fields (EMF) Health Concerns? 5G transmission towers popping up everywhere

- Why Was There No Debate Over the Pandemic? Share your personal experience on the public enquiry

- The Mental Health Crisis? The health costs of mask wearing and lockdowns on society

- Why are our freedoms and rights being curtailed? (The) Government bills affecting our freedom

- (What if) excess deaths are not related to covid?

15-minute city

This list isn’t complete. Low Traffic Neighbourhoods aren’t on it, nor is the 15-minute city, which is a recent addition to this ‘Against everything’ agenda. This is the idea that the resources that a citizen needs in the city should be available to them within 15 minutes—promoted most notably by the left-wing mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo. This was brought up recently in the House of Commons by a right-wing Conservative MP, which attracted the interest of Jon Elledge in The New Statesman:

Nick Fletcher MP demanded a “debate on the international socialist concept of so-called 15-minute cities and 20-minute neighbourhoods”. “Ultra-low emissions zones in their present form do untold economic damage to any city,” Fletcher continued. “The second step after these zones will take away personal freedoms as well… That cannot be right.”

Since my personal view is that the car and the vast infrastructures that it conjured up is the emotional and economic engine—literally and metaphorically—that sits right at the beating heart of modern industrial capitalism, I’m not well placed to engage with this.

Disengagement

But I think we must engage with this list, since it conveys some deep sense of disengagement, and it is—according to Tom Steward—one that resonated with passers-by and taxi-drivers.

I think there are several things going on here, all at once.

The first is that while this list is a complete ragbag, some of these things are true, and broadly speaking, unjust. The wealthy did get wealthier during the pandemic. Our (in Britain) rights and freedoms are being curtailed by government legislation. Ordinary people are paying for the cost of living crisis. The World Economic Forum is a hegemonic project with a grandiloquent title that seeks to align the interests of different elements of the global elite, finance and politicians included.

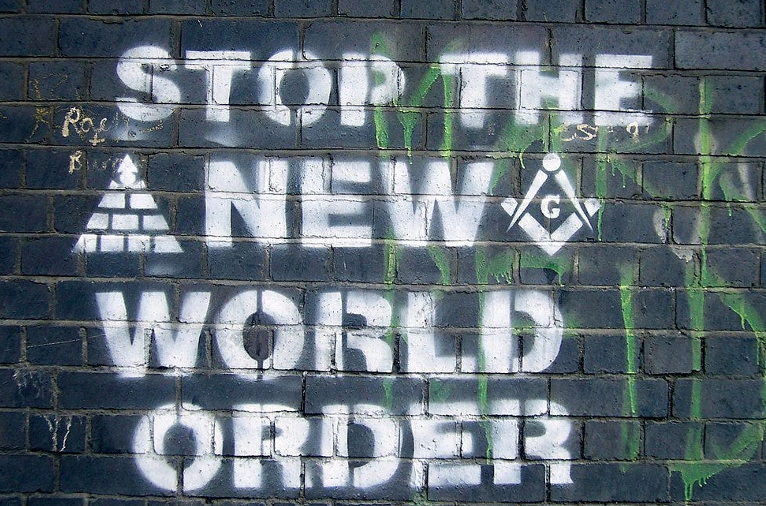

New World Order

The easy way to describe all of this is as a conspiracy theory, and it’s possible to trace the worldview here back to the idea of the ‘New World Order’, sadly not the fine record by Curtis Mayfield but a theory that

a shadowy elite force is trying to implement a totalitarian world government. Proponents of the ‘New World Order’ conspiracy believe a cabal of powerful elite figures wielding great political and economic power is conspiring to implement a totalitarian one-world government.

I went back to an episode of the BBC’s Thinking Allowed that I’d listened to during the pandemic which explored conspiracy theories. It spoke to Hugo Leal, of Cambridge University’s CRASSH programme, who was part of the team that worked on the ‘Conspiracy and Democracy’ programme between 2013 and 2018.

He offered a four part characterisation of conspiracy theories. First, that they are about secrecy, or at least facts which are not publicly acknowledged. Second, they are about power and the powerful. Third, they are about a form of self-interest in which the power promote certain things for their own benefit. And fourth, the “theories” represent quasi-religious beliefs in that they can’t be proved wrong.

(Photo of grafitti by Christian Cable, via Wikipedia. CC BY 2.0)

Globalisation

Historically, the ‘New World Order’ theory tended to bounce around within the American libertarian right, and Christian fundamentalist sects. But in the 1990s or thereabouts it broke out. The high profile fundamentalist preacher Pat Robertson wrote a book with that title, and George Bush used the phrase—he intended something slightly different by it, I think. There’s a longer cultural history here, but suddenly it was all over the place.

But the thing is: the politics of globalisation has a lot of the characteristics that Leal mentions. There’s whole rafts of private or little reported agreements between corporations and governments—for example, Energy Charter Treaties. Power floated away from democratic places and into elites, helped by flows of wealth. Elites clearly promoted things for their own benefit (hard to draw another conclusion from the second Iraq War, for example, or even the way that quantitative easing worked in practice). So it may be that although this populist agitation has the air of a conspiracy theory, it may be rooted in a real experience of the world.

I think there are two aspects here.

Structural violence

First: I wrote a piece here a couple of years ago trying to understand anti-vaxxers, and reviewed some of the available literature. The money quote in this piece, from The Lancet, was about the idea of ‘social solidarity’: that you need to provide some of this if you then want to people to believe you when you ask them to join in with it:

The widespread impacts of the pandemic have illuminated the structural violence embedded in society. Now these communities are being asked to trust the same structures that have contributed to their experiences of discrimination, abuse, trauma, and marginalisation in order to access vaccines and to benefit the wider population.

I think that KTNs and the ‘15 minute city’ are about forms of social solidarity—inclusive, better for health and social outcomes, etc—but if you haven’t experienced this, then you are going to reach for a different explanation.

The second is drawn from my current reading of Dougald Hine’s book At Work in the Ruins. The book is about the gap that is left by the end of modernity. Hine—who is, for clarity, no conspiracy theorist—writes about the difference between knowledge and knowing.

Knowing

One of the problems with privileging science—for all the values that scientists have and the value that science brings—is that it is about knowledge and not knowing. As things start to degrade around us (climate, economies, health, and so on) we try to get to understandings of why this is. He wrestles with different critiques of approaches to the pandemic, and quotes James Bridle’s book The New Dark Age:

Conspiracy theories often function as ‘a kind of folk knowing: an unconscious augury of the conditions, produced by those with a deep, even hidden, awareness of current conditions and no way to articulate them in scientifically acceptable terms’ (p.92).

Hine worries that science isn’t able to carry the weight of knowing of a subject such as the climate change, or of the pandemic. He’s fortunate, in that he commands a high degree of social capital. I wonder if the protestors in Oxford are also trying to fill the gap between knowledge and knowing, but with an experience of the social and economic world that has conditioned them, perhaps rightly, to be suspicious.

—-

This article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.