I spoke last week at an event on the future of the aviation industry in the wake of the pandemic. My short talk was on how aviation would get by in a carbon constrained world—and the answer is: not well. The event was organised by Manchester Metropolitan University and the University of East Lancashire.

Aviation’s core problem is not the 2.5% (or more of carbon emissions it contributes worldwide, although it’s striking that the industry always seems to treat this figure as trivial. Its problem is that carbon emissions are baked into its business model. The activist artist Sterling Crispin calculates that aviation’s emissions per dollar of revenue are up there with the beef industry, widely acknowledged as one of the global warning bad guys.

‘Net’ zero

And even when it is putting its best face on it, the industry acknowledges that there’s a lot of ‘net’ involved in getting to ‘net zero’ by 2050. The UK Sustainable Aviation Group, which represents all its major aviation players, has more than a quarter of its 2050 zero emissions coming from offsets. (It doesn’t call them this…) Given the speed at which offsetting is being critiqued as an ineffective solution, I’d say that is a significant problem.

The reason for this is that aviation needs dense energy, especially for long haul, both for reasons of thrust and for reasons of weight. (This, again, is the industry’s own view).

There are some gains to be had from improved aircraft design, and some from redesigning flight paths, especially for takeoff, but these both take time. The replacement cycle for new planes is 15 years, and many fly for 25 years. Realigning flight path is the stuff of international negotiation.

New fuels

The other bets the industry is making is on biofuel and synthetic fuel. To read some reports, the industry just needs to mop up almost all of the clean biofuels available worldwide and its problems are over. But that’s not going to happen. There’s competition for biofuels and there are other industries where the emissions reduction effect is greater. The UK Committee on Climate Change reckons that about 10% of biofuels ought to end up in the aviation sector.

Synthetic fuels basically convert energy into liquid fuel—energy into energy, in other words—by sucking carbon out of the air. Aviation bosses are on the record as saying that this is essential to the future of long-haul flight. It might work. Chris Goodall, the respected environmental commentator, reckons the technologies are proven and we just need to scale it. But right now we’re still at the trial stage, and it’s not clear how much (clean) energy you need to put in to get liquid fuel out, or what the eventual price point is likely to be.

Then there are the alternative power solutions—battery and hydrogen, as in other mobility sectors. These are currently at the demonstrator stage. The current industry view (for example from Airbus) is that hydrogen is likely to scale better than battery. We might be 20 years away from flying 100 people a 1,000 kilometres in a hydrogen powered plane. But the first generation of hydrogen planes is unlikely to come into mainstream service until the 2050s (two replacement cycles away), and the current view is that this won’t work for long-haul. The most effective hydrogen planes probably need a significant redesign to accommodate enough fuel, but the more radical the design, the longer the testing and approval process.

All of these things were known before the pandemic.

Business aviation decline

There’s another issue that was visible before the pandemic and has been accelerated by it. This is the proportion of business passengers in the passenger mix. In the UK this has been in steady decline for 20 years. This is likely connected to changing attitudes to work and to family among businesspeople. But now, as investors put pressure on businesses to reduce emissions, business travel is in their targets, as Michael Skapinker observed in the FT (link to ungated version):

Companies are not only re-emphasising their environmental goals post-Covid: they are linking them to their travel policies. Nestlé last month said that its “net zero” goal required not just changes in the way its agricultural suppliers operated but also a reduction in business travel… Many business travellers learnt during lockdown that much of the flying they did before was not necessary anyway, and they will now concentrate on trips that matter.

The airlines reckon that they can repurpose their business class seats for ‘luxury travel’ (well, maybe), but there’s a bigger problem here. Once the business market goes, the economic argument for aviation—always the first response of the industry to criticism—also goes, and with it the political cover for expanding aviation. As it was, the economic models used to justify Heathrow’s Third Airport by the Davies Commission were hanging on the thinnest of assumptions. Other privileges, like the industry’s zero-tax regime on fuel, also start to look questionable.

Carbon prices

And I haven’t even mentioned the carbon price yet, but the projected climb to circa $100 a tonne by 2030 will also hurt. All of these issues suggest increasing costs and serious business model challenges. The industry talks about getting back to its projected numbers by 2024 or 2025. I’m more sceptical about this.

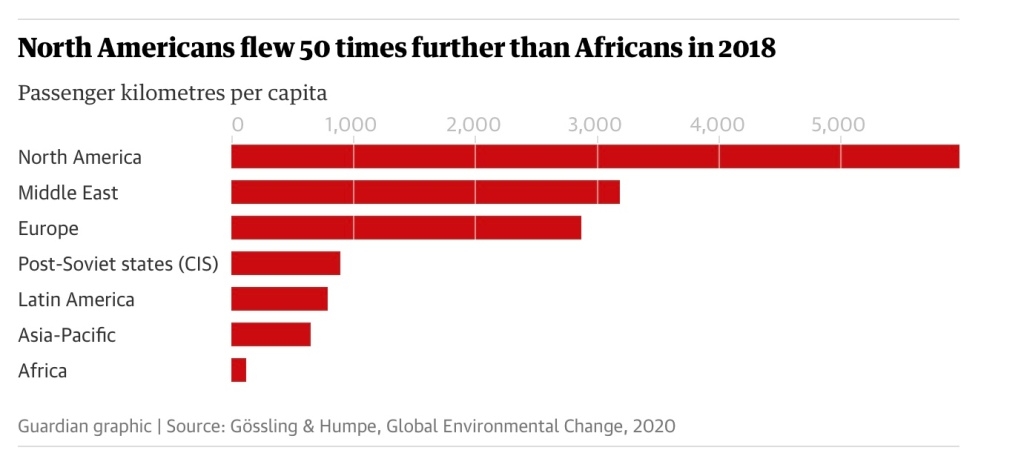

But: I do want people to have the opportunity to travel, in ways that are environmentally, culturally, and socially respectful. All the same, it’s alway worth noting that flying correlates strongly with income, nationally and globally. In the UK, 15% of people account for 70% of all flights; globally less than 20% of the world’s population have taken a flight.

When I was researching some of this, I realised that the aviation system is designed the way it is because air travel is an exact contemporary of the oil industry, and because early airship materials technologies weren’t good enough.

Zero emissions airships

But I have seen a design for 21st century zero-emissions airships that can carry substantial loads, or passenger numbers, powered by solar and storage. They fly lower and slower than planes, but they have other advantages, beyond the environmental gains. They are all-but-silent, and they take off vertically, like a helicopter, from a space the size of a football field. There’s more to be said here and I’ll come back to some of the substance in another post.

The use of airships would require a change in business models and in our expectations of travel. The version I saw, in 2010, had reached proof of concept stage. I went back recently to Bill Dunster of Zedfactory, who had designed it, and asked how the project had progressed. It had got no further, he said: he couldn’t find an investor willing to put up the money to get to demonstration stage. But if we’re really serious about a zero-emissions aviation sector by 2050, this ought to be what our innovators are working on.

A shorter version of this post also appeared on my Just Two Things newsletter.

Teaser photo credit: By Quintin Soloviev – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71173464