I’m thrilled in this episode to share the first part of a two-part interview in which David Holmgren shares his journey with permaculture design process over the decades.

Scroll down to access the full transcript of this conversation, with huge thanks to David for sharing the historical photographs which really bring the story to life.

Note that in collaboration with David I had also previously created a downloadable PDF showing the timeline of David’s design process journey that might provide a helpful supporting reference.

Finally, be sure to check out the brand new Reading Landscape with David Holmgren documentary project website which is so closely related to this episode.

The Full Interview Transcript (Edited for flow and readability)

Dan Palmer (DP):Welcome to the next episode of the Making Permaculture Stronger podcast. I’m super excited today. I’ve travelled about half an hour up the road and I’m sitting at a permaculture demonstration property and home called Melliodora. Sitting next to me is David Holmgren.

David Holmgren (DH): Good to welcome you here.

DP: I’m very excited to be here with this microphone between us and to have this opportunity to have you share the story of your journey with permaculture design process over the decades.

David and Dan co-teaching in 2018

DH: Yeah, and that’s something we’ve worked on together in courses: our personal journeys with that. Certainly through those courses, working together has elicited and uncovered different aspects of me understanding my own journey.

Childhood

DH: Thinking about design process through the lens of childhood experiences, I was always a constructor/builder, making cubbies, constructing things and yet never had any family role models for that. My father wasn’t particularly practical with tools, and yet I was always in whatever workshop there was in our suburban home as a young child. So making things, imagining things which don’t exist, and then bringing them to life was definitely part of my childhood experience.

I don’t know, particularly, why in my last years of high school I had some vague notion that I might enrol in West Australian University in architecture. But I left to travel around Australia instead because I was hitchhiking mad in 1973. And in that process, I came across a lot of different ideas to do with the counter culture and alternative ways of living.

Studying Environmental Design in Tasmania

Most significantly, I came across a course in Tasmania in Hobart called Environmental Design and I met some of the enrolled students. I’d realised by that stage that I was not cut out to do any sort of conventional university course. I was too radical and free in my thinking and wasn’t wanting to be constrained within any discipline or accounting for things through exam processes.

DP: What age were you?

DH: I was 18 at that time, and this course in Environmental Design really attracted me. Undergraduate students, who were doing the generalist degree in environmental design, were sometimes working on projects with postgraduate students who were specialising in architecture, landscape architecture or urban planning at the post graduate level.

Mt Nelson campus where Environmental Design School was part of the Tas College of Advanced Education 1970-80

There was no fixed curriculum. There was no fixed timetable. Half the staff budget was for visiting lecturers and outside professionals. There was a self assessment process at the end of each semester, which then led to a major study at the end of the three year generalist degree. There was the same self assessment process for the postgraduate level. So you got up to the finishing line, and then had to show your results, and that was to a panel that included outside professionals that you had a say in choosing.

DP: Suitably radical.

DH: I believe it was the most radical experiment in tertiary education in Australia’s history. Set up by visionary Hobart architect, Barry McNeil, who saw that there was no point teaching design professionals a specific set of skills, because the world was changing so fast that by the time they came to practice, those skills could be irrelevant and that you had to teach them more how to problem solve, how to think, and that they would find and develop the skills that were relevant that way.

So that’s what led me back to Tasmania the following year to enrol in Environmental Design. As part of that first year, I explored a lot of different subjects. I was actually doing the backyard self sufficiency thing in a rented house and was documenting the organic gardens, the compost making, baking bread at home, all of that self reliance (that I would call retrosuburbia now) in a rented house was actually part of my study project.

The book that came out 44 years after David’s early experiments in suburban self-reliance

I was also involved in projects with postgraduate Planning students, working with urban conservation activist groups, trying to stop high rise development in the historic Battery Point precinct. Setting up a shop front information for the community to explain planning law and plot ratios of how big you can build a building for how much open space and all of those sorts of things.

So I ranged across quite a diverse interest area, and I met a lot of people that came to environmental design, if you like, as refugees from all the design courses around Australia. So it gathered all the radicals at a time when most people went to university in the state where they lived. Whereas more than half of the students in Environmental Design were from outside of Tasmania. And of course, the whole interest in ecology was a huge focus and the crossover between ecology and design.

DP: That was a theme of the graduate school?

DH: Well, it was something that was identified as a huge area of interest of so many students. And at that time, so much so that they felt they needed to have an ecologist, actually on the staff, because most of the staff were designers (landscape architects, architects, engineers and planners). As an undergraduate student I was on the selection panel for the person who ended up becoming my supervisor in the course. So it was a context where I came across a lot of radical ideas in design.

But I still felt quite the outsider. I can remember a particular seminar that was about the design of the Australian backyard. People within the department were basically decrying how terrible backyards and front gardens were designed and how pathetic and hopeless it was people doing it themselves.

I can remember being really outraged and getting up and on my soapbox and saying, look, this is one of the last things that Australians still do for themselves – they design and create their own gardens and backyard spaces.

Hardly any of them build their houses anymore. Are we a radical design school, intending to extend design literacy and design capability as a universal literacy, or are we about commandeering and colonising another space? Taking something else off people and professionalising it.

So I have a strong memory of that, being part of my early thinking about design, that design was sort of a literacy that should be universal.

David more recently speaking to the reality and potential of the great Australian Backyard

DP: It’s exciting for me to hear permaculture bells going off, because there’s already that pre existing overlap between ecology and design. Then when you bring the flavour of being in control of your own design processes and designing your own spaces, you were well on that trajectory already.

It doesn’t sound like it was that kind of school where they said “here’s the design process you’re going to use the rest of your careers.” Were you getting a feel for a kind of approach to design or process at that stage or was it still quite open?

DH: Yeah, it was very free and open, and I suppose within the design professions, environmental design was either regarded as the best course in Australia because it involved outside professionals. You had to do the postgraduate degree part time and have a job in the field before joining the professional association. So there was a huge amount of practical reality that was encouraging to design professionals. Other design professionals regarded it as the worst course in Australia because people weren’t required to actually sit at a drawing board or learn any particular thing, classic principles of architectural design, or anything.

I remember being aware of quite a strong interest in Ian McHarg’s ideas. There were also others that involved designing in perhaps a different way, like George McRobie, colleague of EF Schumacher, famous for of course, writing the book Small is Beautiful, which was published just a year before I started Environmental Design.

George was there for six months teaching the whole intermediate technology notion of designing an appropriate technology suitable to scale especially for developing countries rather than just imposing large scale systems that were inappropriate to context. So there was certainly different design contexts and also design processes, but certainly there was no clear didactic direction. The whole thing was a chaotic exploration.

DP: You said you were documenting what you were doing in the rental with the compost making and everything. Were you also paying attention at that stage to the process side of things?

DH: Not so much, I think I was to some extent quite outcome oriented. But yeah, definitely grappling with that process of how you record and evolve ideas on paper, rather than just literally starting something with your hands, which is how a lot of people do things in the most rudimentary design process. So, definitely that thinking through and documenting ideas and then implementing those, but I suppose with limited awareness of the process.

It was in that first year that my interest really gravitated around food production and more broadly, agriculture, as humanity’s prime way for providing for its needs. And looking at that crossover between, if you like, landscape architecture primarily as a profession, and ecology, and how that applied to agriculture. I could see the overlap between two but not between the three.

I saw overlap between ecology and agriculture in agro-ecology ideas and organics. Although organic farming began in the 1930s, it was really incorporating early ecological ideas in its reaction against industrial farming. So I could see crossover of any two of them. But I couldn’t see anywhere where all three were brought together.

So agro-ecology, for example, didn’t seem to have much of a design focus. Certainly not a physical landscape layout, how the things relate in space. It was mostly concerned with agronomy, husbandry, those processes.

There was some crossover between landscape architecture and agriculture but really as cosmetic design overlay in some particular affluent parts. Or the conservation of agriculture in a larger sense, like McCarg’s work to protect agricultural land from inappropriate development and prevent conflicts of different types of land use; the whole zoning idea. But that was treating agriculture as a system with some sort of planning design overlay but design was not actually involved in the essence of agriculture itself.

DP: And the overlap between design or landscape architecture and ecology?

DH: Yeah, well, for example, one of my teachers in the course who I had a strong connection with was Phil Simons. She was one of the first landscape architects in Australia to use, in quite a few of her designs, local indigenous species. So we had debates and discussions about native versus exotic in those years. She was one of the pioneers of that sort of thinking; how can landscape designer create spaces that can support the diversity of nature and especially indigenous species.

DP: Well, that’s great. I haven’t heard it quite that way before, it’s so clear. And you had yourself a very juicy question. Or a space of how would these things overlap that obviously influenced the course of the rest of your life.

Meeting Bill Mollison

Bill Mollison during a plant stock collecting trip around Tasmania in 1975.

Writes David,

“My close and intense working relationship with Bill during 1974-1976 brought together the ideas and the practice which we came to call permaculture”

DH: It was at that sort of pivotal time that I met Bill Mollison, and he didn’t strike me as a designer, and I don’t think I was looking for that.

I suppose I’d already come to a view that a lot of biological science was highly reductionist and, in fact, even within ecology, there was this tension between reductionist approaches, which would be regarded as mainstream approaches to science, and the more holistic.

So I was very much looking for that and then I met Bill Mollison through chance. He was at a seminar in Environmental Design. He wasn’t running it. He was just someone who made some comments that I thought were really interesting. I went to speak to him afterwards and realised oh, this person thinks ecologically. Holistically.

Note: see also this short article entitled A Chance Meeting

Through chance he invited me to come to his place and I was looking for somewhere to live and I was also a bit disabled because I had a broken collarbone as a result of motorbike accident. So I suppose it was also him taking in a homeless waif.

We began a discussion about what I might focus on in second year of Environmental Design. At the time, he was a lecturer in the psychology faculty, a senior tutor actually. The connection with design was really not through him at all. Particularly, as I worked with him, I didn’t see him primarily as a designer. He was an amazing polymath, a genius, and primarily an ecological thinker.

DP: And was he lecturing in psychology at the same school?

DH: No, at the older tertiary institution, the University of Tasmania. I was at the new College of Advanced Education, as it was then called where the Environmental Design School was.

DP: And you were saying you had this hankering for a more holistic approach to ecology and he was an example of that. So were you learning a lot from him early on, soaking that up?

DH: Enormously. Our relationship was very much student and mentor.

Co-originating the Permaculture Concept

First page of part 5 of the articles by David and Bill published in the Tasmanian Organic Gardener and Farmer in 1976, two years prior to publication of Permaculture One

DH: The seed of the permaculture idea came in a discussion towards the end of ’74 in Bill asking me, knowing how free Environmental Design was, “so what are you going to work on next year? What are you going to look at?” I said, “you know that I’m interested in this crossover between these three things that don’t seem to cross over at all.”

DH: When I put that to Mollison, that’s what I want to work on, of course, he always had a million ideas and he said, “Okay, well how about this for an idea. If in most places on the planet, nature creates some sort of forest as an optimal ecosystem response to climate and geology and landscape to optimise production and diversity from a sort of an ecological point of view, why does agriculture, if not look like a forest literally, function like a forest? For example why is it not dominated by perennial plants? Why is it dominated by annual plants?”

I said, ‘That is perfect, it’s a design question, but it’s fundamentally looking at the design that nature creates, and why don’t we appear to be using that in our prime activity on the planet, agriculture by which we feed ourselves.’

I regard that discussion as the seed of the permaculture concept.

So I started sort of working on the permaculture ideas, when I started the next year in ’75. And it basically consumed all my time, full time. The staff were concerned that I wasn’t doing anything else. But I was free to do that. Mollison and I were developing a permaculture garden at his property on the fringes of Hobart, two and a quarter acre semi rural property about the same size as this place Melliodora.

It had forest on it, and he had owned it for some time and he’d defended it and saved it from the great ’67 bushfires not many years before I was there. There were neighbours and other people in that area who were developing self reliance as part of what we were on about at that time.

A lot of the interest initially was around what you would call economic botany, the exploration of useful plants, the components from which we might, build a permaculture system. Obviously perennial plants and especially trees. So there were a lot of elements that weren’t primarily design process in that.

Even though I was a bit separated from and critical of a lot of what I saw in the design professions and even in environmental design, and I was off on this other tack, with Mollison as my mentor who I did not see really as a designer, so I see the design side of permaculture, in a way came more through me, through the lineage of environmental design and the radical ideas of design that were part of that school.

DP: Wow, so 1974 was a hell of a year!

DH: Yeah. Two years after the Club of Rome Limits to Growth report, one year after the first oil crisis that precipitated the Western world into the first economic recession since WWII.

Of course, 1972 was also the election of the Whitlam government in Australia after 23 years of conservative government, and a whole huge cultural explosion of different ideas and different possibilities, which led to the great constitutional crisis of 1975. And it was the end of the long running war in Vietnam and eventually with the American defeat in Vietnam although Australia pulled our troops out in ’72.

So there was a huge social, economic and political turmoil at that time and an openness, certainly in academia, to new radical ideas. Environmental design as that radical school ran from 1970 to 1980. And then it was basically emasculated, turned back into a conventional design course and moved from its Hobart base to Launceston. So it’s very emblematic of the ’70s.

DP: You got your timing right!

DH: Yeah, the timing for permaculture, generally the huge interest in ecology and related ideas in science. For example, the embodied energy concept; How we use energy as a measure of human systems. In 1979 I went to the ANSAS conference in Hobart and there were five papers on net energy analysis of agricultural systems. Move forward a decade, there would have been none of that.

So there was a huge interest in all sorts of things that included design process. I mean, just as an example of that first year I was there, during that project I worked on with the Battery Point urban conservation. There was another project, working as consultants to the State Department of Planning as to how to do, for the first time, a strategic plan for Hobart with community consultation. Because up to that point, planning had just been engineers and staff, deciding where I imagine freeways are going to be built in new urban expansion and whatever. So those ideas of people being involved in design process in things that affect them at that social level was, of course, part of that period.

DP: Would you say that period, or that pivotal conversation about what you’re going to do with your project the next year was a kind of a moment? And did that culminate with Permaculture One?

DH: Well, I think in a lot of ways for me that did culminate in the publication of Permaculture One in 1978. And the huge interest that there was at the time. For Mollison, that was a stepping stone to moving out of the university, giving up his tenured position, and going to spruik permaculture to the world. Not just through the counter culture and the first areas of interest but more broadly and with huge popularisation. Whereas I felt at that time, not quite a fraud, but I didn’t have the broad base of experience that Mollison had in some areas and also being a generation older than me apart from anything else.

So my interest was in building my practical skills. In ’76, I completed the Environmental Design degree and I didn’t go back to do the postgraduate degree because I was actually at that stage, so sick of or beyond wanting to think about things academically and I wanted to do things with my hands.

David Holmgren at backyard greenhouse project at Arthur St Hobart 1979

Initially, a lot of that was already happening as gardening, forestry, ecological hunting, but also I had a big role in building and I built a big timber barn on a property that Mollison and I and others had bought to develop as a permaculture place.

I worked as an offsider with a friend of mine who was a builder my own age who ran his own building business. We were doing quite complex building projects and learning by doing.

I didn’t like the idea of design, in whatever field, disconnected from the practice of, implementation. That separation wasn’t really viable, and that is apart from it’s class implications that there’s the designers and plodders who implemented. I didn’t respect any of that sort of idea.

I was much more interested in doing stuff and building a skill base. But in that process, I suppose beginning about ’76, I was starting to build a skill base for advising other people. I had a self directed apprenticeship really, working on other people’s projects, some paid, some voluntary, doing the odd design consultancy.

David in Jacky’s Marsh 1978. Photo by Bruce Hedge

David making pressed mudbricks Tas Down To Earth Festival 1978 Press photo

That led to my mother in her middle age, out of the blue, buying a 180 acre rural bush property on the far south coast of New South Wales. And I thought, “I need to go and help her get set up and build a proper passive solar house and get gravity feed water supply systems and appropriate fencing so she can have gardens and be fire safe and implement all those ideas.”

Meeting Haikai Tane

DH: I’d been working at that stage continuously from when I left Environmental Design and graduated at the end of ’76 to ’79. In those three years, I’d worked in lots of different ways. But I’d also discovered my second mentor in New Zealand, Haikai Tane, who in a way I regard as my second mentor in permaculture.

I met Haikai at the Down to Earth festival organised by ex Deputy Prime Minister Jim Cairns, as part of the countercultural movement in Australia, the Down to Earth movement. I’d been there at that festival where there was this huge interest in permaculture. I hadn’t seen Bill for quite a while and we ran up a workshop under a big shady tree with about 150 people.

I met Haikai after that workshop and we wandered around this thousand acre grazing property (near Bredbo on the Monaro) exploring things and he made a comment about something that Mollison had said that just made me sit up. He said, “Mollison mentioned that this degraded grazing land needed gorse spread over it,” (which is of coarse a noxious weed), to improve the land damaged by all the sheep overgrazing. Typically confrontational comment, yeah. And Haikai said, “I’m not sure that I agree with Mollison about gorse.” And I thought “this is going to be a conventional argument about invasive exotic species.” He said, “I think Briar Rose is a more appropriate species for this.” Which is of course, another spiny noxious weed. And I thought, who is this guy? What does he know?

Reading Landscape with the Land Systems Approach

DH: We spent a whole lot of time looking around that landscape and Haikai’s knowledge in reading the landscape just fascinated me and we spent days together. He invited me back to New Zealand to help set up permaculture in New Zealand, the Permaculture Association of New Zealand.

note: learn more about David’s approach to reading landscape here

He was already a member of the Farm Forestry Association of New Zealand, the Soil Association (the national organic organisation) and the Tree Crops Association. He was actually trained in Law, Planning and Geography, had studied at ANU and knew the Monero country very well, had worked in British Columbia, but had really adopted New Zealand as not just home but spiritual home almost. Then taken a name which was Japanese and Maori, but he was originally Australian. Again, much older than me, but not as many years difference as with Mollison.

Haikai Tane, Waitaki Basin South Island N.Z. 1984 Writes David: “I took this picture during my second visit to the N.Z. high country. This barren”naturally treeless ” area has a semi arid climate with very cold winters, but the growth of suitable species of trees on the fresh glacial soils is nothing short of spectacular as illustrated by the 15 year old plantings in the valley. Haikai and his love of the NZ high country was very influential on the development of my ideas.”

In working with Haikai in New Zealand in 1979, and then again in 1984, he taught me a lot about the Land Systems approach to understanding land. He’d actually done the Land Systems study of that high dry cold grazing country of the South Island for the New Zealand government Lands Department.

Mapping all of the land in a way that integrates the geology, the topography, the climate, and what he called the biophysical resources of soils, plants and animals that express those underlying energetic and geologic forces. And that was the basis of what we would call sustainable land use. You had to have everything mapped on to those patterns, both at a large scale, but also down at a fine scale.

DP: I know you learned a lot of holistic ecology with Mollison and I know you moved around the country a lot. So what was the difference in reading landscape? Was it kind of like going deeper or was it in different direction?

DH: Look, I was already in that process of reading landscape in the early research for permaculture. Because I would go and visit old forest arboreta and abandoned gardens, places where people have done stuff, and then nature had sort of taken over. I found those much more interesting from a permaculture point of view, to give instruction of the intersection between humans doing stuff and nature doing stuff; than going to some pristine wilderness. So I was already developing those skills and a lot of that was about ID, what is this tree? where is it growing? Why is it there? Those sorts of things.

Hot-off-the-reel teaser for the www.ReadingLandscape.org project

So when I met Haikai, his mastery of all that, and especially a deeper understanding of soil, not in the sense of the agronomist’s focus on the condition of the A1 horizon, the topsoil, but understanding the regolith, that deep structure underneath that often determines the moisture availability and possibilities of deep nutrient mining, and different geological strata that would produce quite different ecosystems, and had quite different potential to be developed and quite different vulnerabilities to land degradation processes.

DP: Is that an actual word, regolith?

DH: Yeah, that’s describing the material underneath from which soils emerge whether that’s the bedrock or deep deposits of alluvial material. And in New Zealand, the newness of the country compared with Australia made all of those reading landscape skills, so much sharper, so much easier to see. Whereas in Australia a lot of the processes are so subtle, so ancient, it’s harder to see them.

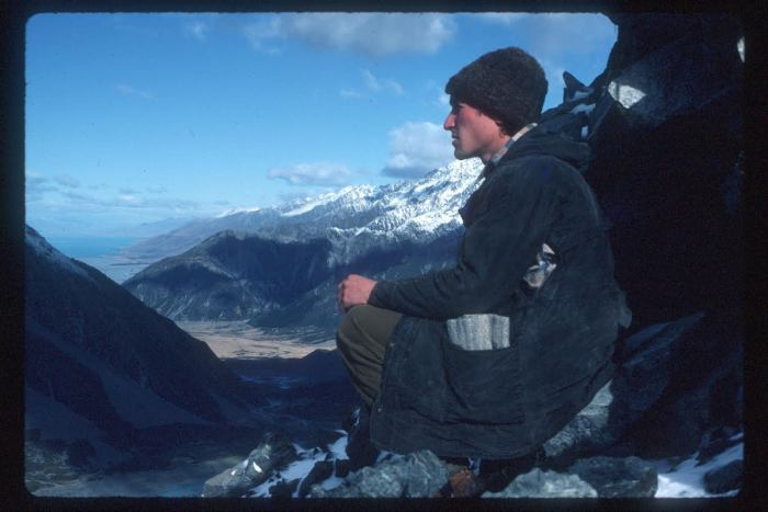

Self portrait Mt Cook NZ 1984

The constraints of freehold land tenure for permaculture

DH: Haikai also convinced me that the permaculture vision of broad acre integrated land uses of agriculture, horticulture, aquaculture, beekeeping, forestry, all of these things being integrated, couldn’t come about under our freehold land tenure system.

So that understanding, from land law and from history of our ancestors before modern land title and the enclosures of the commons and all of those issues I learnt that the way we own and control land is actually a huge factor in how it could be designed. So, it was drawing me into understanding those sort of cultural institutional forces that shape design.

Strategic Planning

DH: I suppose the most important learning with Haikai was moving away from the master plan idea; design it on paper and then implement it. Which is always a bit problematic when that methodology was taken from designing the built environment and trying to master plan a garden or landscape, because you’re dealing with biological entities that change and complexities of soil you don’t fully understand. In urban planning where cities are so big and complex master plans are similarly problematic. You could say, of course, that Christopher Alexander was very strongly critiquing master planning within architecture too, that it doesn’t really work. I was sort of vaguely aware of that critique, because Alexander was one of the thinkers influencing people in Environmental Design. But because my focus was more biological, I didn’t pick up so much on his work.

Haikai really introduced the framework of strategic planning, which had become a tool used by urban planners, but it came out of the military, as he explained it. Military planners had to act with limited knowledge and where they didn’t control all the factors and that idea of having frameworks of action, but you don’t really know how that is going to express itself in final design form. We started applying strategic design process to what we call tree crop agriculture; how do you not just have grazing animals around a landscape or annual crops, but these permanent, long lived structures of tree crop. Like me Haikai was a tree crop nut; he was obsessed with trees. So the application of that sort of design process was very much part of learning from working with him.

DP: This is really fascinating and you were saying earlier even before Haikai, you had a sense it wasn’t viable to have a separation between in some cases, white collar design and blue collar implementation. That was already an irk.

DH: Very early on.

DP: So that was already there and Haikai really helped you go deeper into this?

More recent photo of Haikai

DH: Yeah, because he was very practical, hands on, as well as working in high level consultancy, to Government and business. He had a consultancy job working for the state government of New South Wales to review the Sydney basin regional plan, the whole of the Sydney metropolitan area. It had become a political hot potato internally, and they decided, unusually in those years, to get an outside consultant, and he somehow got the job. But in the process, he went and lived in five different locations around Sydney, always traveled with taxi drivers and explored the multiple cities and spaces that Sydney really was, rather than the myopic view, as he said, of the planners sitting in the tower overlooking Hyde Park. They had a view of the city and the suburbs, whereas he said Parramatta was already the the largest retailing centre in Australia. He identified as 21 centres in Sydney that had city level function. So he was an iconoclast in many different ways within the planning profession, but he was also a beekeeper and a totally hands on person. You know, so, that practical doing, as well as design and thinking.

Yeah, so he was a big influence on my whole design process. In 1979 he encouraged me to get a camera and record what I see in the landscape. So he really put me on that lifelong journey of reading landscape. And that certainly also began how I applied that in my consultancy work. And then, in trying to design in ways that is sensitive to, not just the form of the land, but the actual different types of land – recognising that first. So using that Land Systems approach, which had mainly been used at a macro scale, bringing it down to a much smaller scale of permaculture sites to decide where are the changes in land and understanding those first and mapping those before you start carving up the land into its uses or allocating it to different things.

Permaculture in the Bush

DP: So you’re well on truly into the domain of design process here, where a key part of it has to be deeply immersing in what’s already there, what’s happening, what are the land units.

DH: The first really big project in applying that was my mother’s property on the south coast of New South Wales. Because it was 180 acres of forest. There were 12 different eucalyptus species, three gullies, a boundary to a permanent creek, and two different geologies. As I analysed it, in a case study booklet that we produced on it called Permaculture In The Bush, it had three different Land Systems.

Permaculture in the Bush – Wyndham Far South Coast NSW, 1984

I used that macro, stand back, look at the big patterns first, before going down into the details. Looking across the landscape and saying, okay, where are potential house sites identifying five of those and and then checking them against different criteria. So I started using ways of scoring things to come to a complex decision making way, rather than getting locked into single factor design which saw a lot of those sort of processes.

It was also interesting as a design process for me, because I had the contour maps, and I had photographs my mother had taken, and I had her to interrogate, but I actually didn’t get to the property for six months into the project. I was in Tasmania and then we were back in Western Australia, selling the family home.

When we finally arrived at the land and drove down this bush track, I already knew what was around the corner from just going over contour maps, and trying to get another bit of information. It was squeezing more information out of it. So it was a very weird sort of experience, but a very useful one in terms of design process to explore something that closely through indirect means and then set up camp.

That very process of thinking ‘No, don’t make any assumptions. You’ve got a whole lot of stuff in your head. None of it means anything at the moment.’ The primary process of setting up a basic camp. And the first lesson about, ‘don’t set it up on the best spot! Because that could be where you’re actually going to develop.’

David free hand chainsaw ripping blackwood for door and window sills Wyndham 1979

There was also a huge number of practical learnings there in directing earthworks and timber milling, directing other people’s work in building a passive solar house. I had worked a lot in that side and I was actually really passionate about passive solar design. So ironically, that project was also quite a consolidation for me, in practitioner terms, as an ecological builder, more than an ecological farmer. It took me many years to sit and look back and say, ‘Well, actually, I’ve been more of a builder and more of my design work has involved a lot of the nonliving elements, the infrastructure, the earthworks and water supply systems and fencing and all that infrastructure as well as with building. And that knowledge base from the practical arts of woodworking and the processing of timber from tree to saw milling, drying, processing using timber was a greater development of skill in that area than I did with horticulture, let alone animal husbandry.

Erecting posts at Venie’s Wyndham 1979

DP: That’s fascinating. You were already very hands on with building and stuff. But to then be working with contractors as well which is another step and working indirectly through them and collaborating.

DH: Well, it was mostly friends working at mates rates, jack of all trades. So it was the beginning of that sort of, artisanal building process and definitely doing a lot of thinking things through and planning on paper, and then being prepared to change the design.

Of course, when you are actually doing something yourself that you have gone to huge efforts to put on paper, but you see yourself as a learner, and you are at the receiving end, it’s very clear that you will change the design. Whereas when it is separated, and there is someone invested with the authority of being the designer, and this person, the builder or someone further down the chain is experiencing the disconnect between the design and reality, there’s a power relationship, a whole lot of investment that it’s hard to bring that through unless of course those designers very deliberately working in that way.

DP: Yeah, it’s almost always like in that model, when there’s a clash between reality and design, the native inclination is to try and make design win. Which of course, it ultimately cannot do.

From Permaculture in the Bush, Wyndham, late eighties

Setting up Holmgren Design Services (HDS)

DP: I’d be really keen to hear about your transition into professional design consultancy. Is that an appropriate thing to tell us about next?

DH: Yeah, because, that project on the south coast in New South Wales was really the final or most important project that really led to me setting up Holmgren Design Services as a registered business in 1983. It was just a couple of years after completing the initial phase of development of the property with my mother. Also the documentation that I took to the first permaculture convergence in 1984, of a case study of that property.

I presented two papers at the convergence. One was on reading landscape, to the young permaculture movement where there had already been four years of people having done a permaculture design course, rushing out enthusiastically trying to design the world, and not necessarily making a very good job of that.

I was introducing the idea that skill in reading landscape is one of the core skills for a permaculture design. As a consultant having to come onto a site where people don’t necessarily have a deep multi-generational historic connection with the land, where there’s not necessarily good mapping of soils or even topography, even decent contour maps and having to advise on key design decisions and needing to be able to read a lot of things very quickly in the landscape.

So there was that and there was the case study because I saw that the ‘talk to do ratio’ in the permaculture movement, felt to me quite high.

DP: The talk to do ratio?

DH: Yeah, that’s what Haikai called it. He talked about how the ‘talk to do ratio’ was higher in Australia than New Zealand. Much higher in America.

DH: So the case study documentation of places that had been permaculture designed, and then implemented, rather than just places where people were saying, “oh, here is something that illustrates permaculture ideas. Great. That’s really good.” But was permaculture thinking actually influencing how that came about? Because that’s that next test of the concept, can people use these ideas to actually end up creating more appropriate systems that reflect permaculture ethics and design principles?

So then to document that design process and how that was implemented. I saw it as important on an ethical level, of being guinea pigs, of trying out your ideas yourself. And so that was all happening around that same time. And in ’84, I also went back to New Zealand and worked with Haikai again, and through the New Zealand Tree Crops Association working on how did these ideas apply to actually implementing the transformation of pastoral landscapes into multi purpose tree crop dominated landscapes?

LSD, Intuition, and “A Case for the Coin”

DP: You’ve talked to me in the past about how you grew up in a very free thinking, rational, intellectual household and you’ve told me a few stories over the years about how during your time with Haikai where he’d give you spontaneous lectures about Lao Tzu and bring a sort of Eastern mysticism flavour. Did that have any impact or bearing on or relevance to design process?

DH: Yeah, well, actually, that reminds me of a story. I suppose I’d see myself growing up as a super rationalist. Even as a child, I would wake up and not remember any of my dreams, probably because the dream world was, like just too inconsistent with reality. There were a few things that broke down that process. The primary one was the experience of LSD made it clear to me there were more things in the human mind that could possibly be comprehended through simple sort of reductionist methods.

Another marker in that was certainly working with Haikai, setting up the site for these workshops over Easter in 1979, on a high country grazing property. We were designing the site “where are people going to park?” “where was the camp kitchen going to be?” “where was the sauna by the stream?”; just designing a small festival space.

Both of us as designers were running through all the factors, circulation here or what if its wet weather, etcetera. Anyway, we got to a bit of a stumbling point where there was one option over here and another there. We’d run through a few of the factors and Haikai said, “This is a case for the coin,” and pulls out a coin and he flips it. I was flabbergasted at this idea that you could actually make a decision, a design decision, based on the flip of a coin.

And then he gave me this lecture on the I Ching and a whole lot of ideas in Eastern mysticism about firstly connecting to a deeper level of your feelings about what is the right thing to do and part of it is your own reaction to this chance decision. But also that you uncover a different way of accessing part of your understanding. So that was one of the stepping stones in that breakdown of that super rationalist control.

Another one was when I was working with my mother, on developing the property, the early stages of the design, and we were refining where the house site was going to be on this 180 acres and looking at gravity feed, water supply, dam site options, all sorts of different factors. The chosen site was fairly thick regrowth logged over bush site. So it involved clearing quite a lot of trees and a lot of thick regrowth.

I’ve been working through with my inclinometer looking at tree heights and because you’re talking about forest trees that were 35 meters tall, and how are we going to make the clearing, minimising impact with retention of trees that we wanted to keep and get full sun access into the passive solar building, and full winter sun access to gardens.

I was trying to do that through thick young regrowth and big emergent trees. I was using the inclinometer measuring sun angles across tree canopies, working backwards and forwards over a period of more than a week. In the meantime, my mother had wandered in and found an old box that had been left with some rubbish and she stood it up, saying, “I reckon the house should be about here.” And as I worked around, I ended up coming back to where the box was. Now it may have been completely dumb luck, but it was interesting that rational evidence based process somehow connecting with something that came completely intuitively.

Stay tuned for Part Two and meantime please a) visit the Reading Landscape with David Holmgren documentary project and b) consider becoming a patron of Making Permaculture Stronger to support the creation of more episodes and articles like this.