The long wave theorist Peter Turchin has turned his attention to Brexit. So, although I had not planned to turn my attention to Brexit again for the time being, it’s probably worth noting what he has to say.

Turchin is best known for his ‘secular cycles‘ theory of long-run political change. By ‘long run’, we’re talking cycles of 100-300 years. He is an evolutionary biologist, and started by wondering if the same resource pressures that shaped species rise and decline generally might also apply to humans. His first approach to this, written with his colleague Sergey Nefedov, researched pre-industrial societies (pdf). When that seemed to work, he started to look at industrial societies as well.

The Turchin model

Before we get to Brexit, it is worth just referencing his model. I’ve written about this here before, so this is a quick refresh.

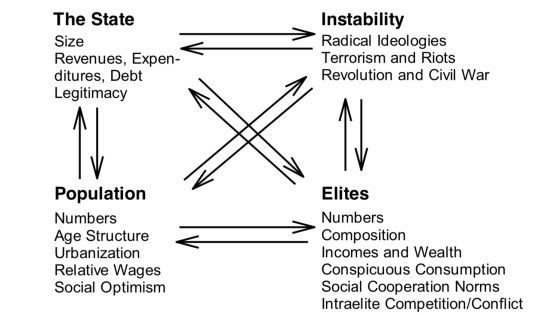

The approximate dynamics of the model are captured here, in a 2013 paper.

(Source: Turchin, ‘Modeling Social Pressures Toward Political Instability’, in Cliodynamics, 4(2))

When it is shown like this, it looks a bit like the universal answer to everything, but in Turchin’s defence, he and his researchers have modelled the relationships here to the point where they are quantifiable. Turchin explains it this way in the paper:

The theory represents complex human societies as systems with three main compartments (the general population, the elites, and the state) interacting with each other and with socio-political instability built in via a web of nonlinear feedbacks (Figure [above]). The focus on only these four structural components is not quite as oversimplified as it may appear, because each component has a number of attributes that change dynamically in response to changes in other structural- demographic variables.

If you want to know more, it’s worth spending time with the paper, which then uses the framework to model political instability in the United States, historically and in the present. But it’s worth noting that “relative wages”, under the ‘Population’ heading, tends to be an influential variable.

The over-supply of labour

When he points this framework at Brexit, it does produce some interesting analysis. The first is about the supply of labour compared to demand–i.e. the oversupply of labour.

(Source: Peter Turchin)

As with the United States, which has been a central focus of Turchin’s recent work,

“[t]he main causes were immigration, the entry of massive numbers of baby boomers and women into the labor force, [and] the export of jobs overseas.

This chart, though, is something of a proxy: it uses the unemployment rate as an indicator of under- or oversupply, and takes 4% unemployment as the threshold of this. Maybe this is good enough. The big dip in the couple of years before 1990 is the overheated economy that was the ‘Lawson boom’, which didn’t end well.

Union decline

There’s a related chart, which looks at the density of trade union membership over almost the same period. Correlation isn’t causation, etc, but we know from other work that effective trades unions are one of the best ways to maintain real wages. Union membership peaked just after the 1970s, the decade when the real share of wages in the UK economy was at its highest and inequality was at its lowest. After that, as a result of Thatcher’s policies, trades unions were subjected to sustained legal and political attack (up to and including violent attack by state agents).

Chart: UK trade union membership

(Source: Peter Turchin)

Relative wages

And just to finish off this, here’s the outcome of those two charts: the relative wage over the same 60-year period show a steady decline, by about one-third, from the mid 1970s onwards. Relative wage: “median (typical) wage divided by GDP per capita, which tells us what proportion of gains from economic growth goes to the workers.”

Chart: UK relative wages

(Source: Peter Turchin)

Turchin’s article also has a 180-year chart on changing social norms around all of this, based on voting share at general elections. There are problems with this perspective (the voter base changes over time, parties fracture and recombine) but the long-run point he’s trying to make is that we see a shift in social expectations in the 1910s and 1920s as the Labour party emerges, and then again in the 1970s and 1980s as Thatcherism rewrites the social contract. For my money, this misses an important historical point, in the mid 1940s, when the Labour post-war landslide creates the welfare state.

In fact, one of the interesting features of these long run landscapes is that there are financial crises approximately every 40 years, and political crises following them along at a distance of about a decade.

But, but, but.

Although Turchin’s piece is full of comparisons between the UK and the US, which he sees as fellow travellers, certainly when compared to France, there are significant differences between Trumpism and Brexit. Of course there are similarities: as British leaders go, Johnson is at least as far to the right of previous Prime Ministers as Trump is when compared to previous Presidents. The willingness of these politicians to bend themselves to help Putin’s geopolitical ambitions is striking. Bannon and Farage slither between the two countries, washed along on dark money, whispering snakes in shady grass.

But there is also a very important difference between the politics of the two countries, which is not explained by real wages.

Politics of interests

For all of the excesses of Trumpism, it remains a politics of interests. It identifies a base of political supporters and finds ways to reward them, through policies which benefit them directly or offer them a sense of worth. Yes, it is refracted through the gridlocked American political system, which allows the rewarding of interests to extend to changing the rules of the system (e.g. through gerrymandering or voter suppression). But, at heart, it is still a political process that a political scientist would recognise.

This is simply not true of the politics of Brexit.

The significant aspect of Brexit is the detachment between political rhetoric, political means and ends, and political purpose. During the referendum campaign, there was some relationship between the narrative that was constructed and the interests of a group of voters. The sunlit uplands of leaving the EU (“the money’s coming home to save the NHS”, and so on) may have been mendacious, but it appealed to voters who had been systematically squeezed, at a personal level and at a community level, by austerity.

Indeed, one of the depressing things about a recent report in The i talking to Leavers in Skegness was the clear and present sense that the morale of the community had been so brutally worked over by our political class that anything–anything–would be better.

Delusions

I’m not going to spend time on the delusions about a no-deal Brexit on 31st October that seem to be shared by the right-wing cabal intent on pushing it through.

OK, then, briefly: A ‘no deal’ exit is not the end of the Brexit negotiations, but the beginning; Britain will take a bigger hit that the EU, not the other way around; there’s a reason why countries trade on the best possible terms with their geographical neighbours; negotiating trade deals outside of larger trading blocs is harder, not easier; the currency markets will be unforgiving; the cost of food will go up. There will also be weird, unanticipated glitches, which will end up on the news bulletins, because the UK and EU exist in a complex relationship of regulation, markets, and supply chains.

Not that any of this matters in the politics of Brexit. The Conservative party has become a party of English nationalists, with a pungent stripe of hedge fund disaster capitalism running all the way through. The Union can go hang, and business? Well, f*ck business. This is not the politics of interests, as it is normally understood. And there’s no easy way to explain this if you use the Turchin model to look at the politics of Brexit. All it tells us about are the pre-conditions.

Betting the house

So what other explanations might offer themselves?

The first is a political one: that if your party is in long-run decline, with a shrinking and ageing base holding onto declining values, you might as well bet the house on one last spin of the wheel. But in practice most parties in this position don’t do this: they work out a strategy that can re-compose their base, rather than doubling down on them.

The second is a moral one: that 30 years of runaway financial markets have detached the elite from the social norms and values of the mainstream, and that the elite find that aligning themselves personally and politically with the interests of hedge funds is vastly rewarding. As Wolfgang Streeck observed, corruption is one of the signs of the end of capitalism.

The third is psychological: that the end of Empire has finally caught up with people who grew up in the shadow of Churchill. This is the politics of people who, as the Irish writer Fintan O’Toole has argued, have constructed an imaginary oppression, in which the masters of Empire and victors in two World Wars are now, somehow, the colonial subjects of the EU. This now fuels their political imaginary, and, indeed, a whole set of imaginary politics. They are the Don Quixotes of 21st century politics.

In fact, all three of these explanations have truth in them, and as they play out each reinforces the others ever more stridently. But they also suggest that we are in a political moment that is fragile and temporary, and one that needs to spin ever faster to sustain its delusions. Each of these three, on its own, could be the clue to how this fantastickal politics will self-destruct. It is a moment of political theatre that will unravel when something, or someone, breaks the fourth wall. The spell can be broken.

Thanks to Ian Christie for alerting me to Turchin’s Brexit article. The image at the top of the post is by Our Future Our Choice.