In their food lab, the twins offer us a tomato macron that is made of tomato seed oil, a sauce from green tomatoes pulp and dehydrated ripe tomato as bottom and top. It is a delicious and innovative tribute to tomatoes, quite representative of the interesting mix of the genuine and simple paired with the sophisticated and elaborated that is their signature.

| The tomato macron of Twins Garden |

Ivan and Sergey Berezutskiy are twins and chefs, who have worked in some of the world’s finest kitchens. In 2014 they opened Twins Garden in Moscow, where they reinterpreted Russian cuisine with modern techniques. The have a keen interest in the ingredients, their origin and their cultivation. Every year they make several trips to different Russian region to discover the most interesting local products. Given the size of Russia, to say that they buy ”local” is not very accurate. As a matter of fact they source a lot of crab from Kamchatka and the distance from Moscow to Kamchatka is the same as the distance from Stockholm to Addis Ababa or from New York to Mexico city and back again!

Recently they took another step by acquiring a 50 hectare farm in the Kaluga district where they have Numibian goats and Jersey cows for milk and cheese, cultivate five kinds of fish and grow a lot of vegetables.

“We follow organic principles on the farm but we are not certified,” says Ivan …. or perhaps it is Sergey? They are identical twins. They try to help us by being dressed in different colors, Sergey in white and Ivan in black, but it still hard to remember.

Another dish we eat is four versions of potato, so simple and yet so tasty! They are not vegan or vegetarian chefs, but they certainly have something to teach most vegan chefs. The Twins Garden ranked #72 in the world according toWorld’s 50 best restaurants.

We (Ann-Helen who is a journalist and my spouse, and I) also visit a number of farms, shops and restaurants and we meet representatives of big corporations, the organic association, the federal vice minister of agriculture and several regional leaders. Before continuing my travel report, just a short recap about the collapse.

When the Soviet Union collapsed 1991, the food and agriculture system also collapsed to a very large extent. Food was heavily subsidized, especially meat and milk and the subsidies took one fifth of the government budget. Food subsidies disappeared and food got a lot more expensive while a large share of the population became poorer. Demand plummeted. The collective farms and stat farms were privatized through slow processes. The distribution system of the Soviet Union and the regional specialization that had been developed also collapsed which meant that farmers suddenly should learn how to sell, food industries should learn how to both buy and sell and shops learn how to ensure a good supply of products. To add harm to injury, Russia also opened up its markets for imports which flooded the market. This was a real shock therapy, it virtually killed people and the farm and food sector. Enormous man-made capital was wasted. Milk production in Russia went from more than 45 million tons per year to 30 million tons per year and cultivated land dropped 35 million hectares from 115 million hectares to 80 million hectares. That gives you an idea of the scale of the collapse.

After various crises and problems the government belatedly realized that the situation was untenable and in 2010 it established targets for self sufficiency, in the range of 85% to 95% for important food stuffs. In the agriculture development program for 2013-2020 substantial resources were allocated to agriculture. When the EU and the US imposed sanctions against Russia because of the annexation of Crimea, Russia responded with an embargo against many food products. This left shelves empty for a while. It also pressed the government to do more and gave agriculture producers a new energy.

In December 2015, Vladimir Putin said that the country should become a leader in organic food, in 2016 Russia banned the breeding and cultivation of GMOs and in a speech in January 2018, Prime Minister Dimitri Medvedev said that Russia would capture 10 to 25 percent of the global market for organic foods.

“One tenth of the 30-40 million hectares that are currently not used could be converted to organic production,” said Ivan Lebedev, Deputy Minister of Agriculture of the Russian Federation, in a panel debate (where I also participated) the 10th October at the fair Golden Autumn.

I am not sure of how sincere the government’s interest is in organic, though. It is clearly in the interest of the government to promote the Russian, the genuine, the organic as part of Russian cultural revival and patriotism, which in turn is part of the political strategy of President Putin. Be that as it may, the government will now provide the organic sector with both hard and soft support.

The organic sector in Russia has been very slow to develop. For decades there were mostly the odd project; somebody with 10 000 hectares of land cultivated wheat, buckwheat or sunflower, for exports for some years and then they disappeared. The domestic market developed slowly and was almost uniquely supplied by imported productz, primarily from Europe.

| The price of organic food is often double, accoording to Tatiana Lebedeva, from the organic portal look.bio. |

However, something has happened. The sector has a unifying organization in the National Organic Union and there are some stable and substantial companies organizing production, trade and retail.

“There is some 300 000 hectares of organic farm land, not even 0,3 % of the agriculture land, and a lot of it is for exports,” says Oleg Mironenko, head of the national organic union and adds that the main organic products on the domestic market are dairy products and meat.

The sale of organic is not (yet) regulated in Russia and many producers claim to be organic, even if they are not.

“Ninety percent of the products sold as organic are not organic,” says Ilya Kaletkin from Arivera that produces, exports and imports organic product and has the organic retail chain Biostoria.

This is understandably frustrating for serious actors, but it is also an indicator of that there is a latent demand.

“When we had our first milk, we were so delighted,” says Edvard Pochivalin of Ekoferma Djersi (Jersey).

That was in May 2017. Since then they have managed to develop the production of a dozen of good hard cheeses of Italian and Dutch style, cottage cheese, butter, ghee and that special sour cream, Smetana. When they bought the derelict and abandoned former kolkhoz in 2016, the buildings were in ruins and trees were growing on most of fields of the 1 300 hectares farm. Together with the siblings Anton Gudov and Elvira Gudova, Edvard and 30 employees are building up a center for organic farming, education and development in the Tula region. Currently there are 60 Jersey cows on the farm but the plan is that there will be 5 stables with 200 cows each in organic production. Among the other plans is a combined orphanage and elderly care center.

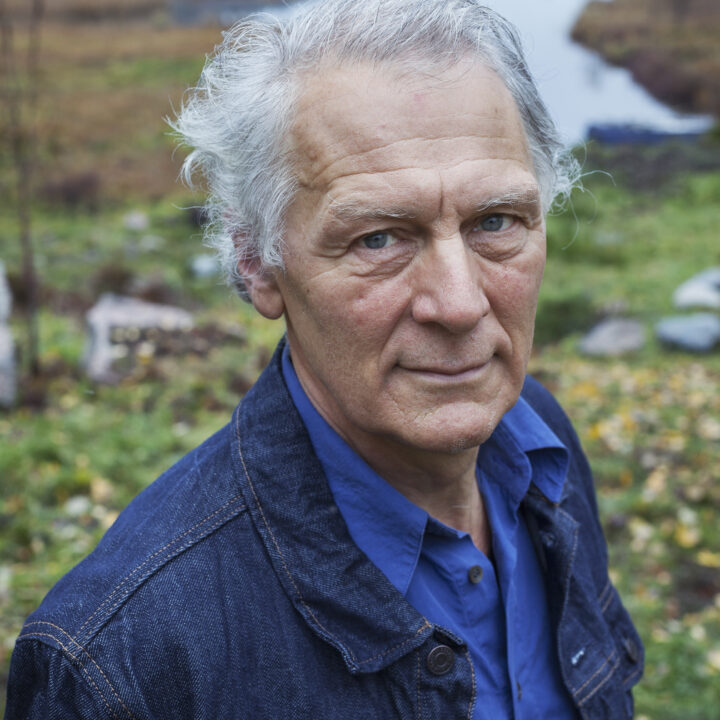

| A worker at Ekoferma Djersi |

Anton, Edvard and Elvira were in business (international law, finance and construction) before taking up farming. To compensate for their lack of knowledge they visited some hundred organic farms and dairies in Europe before starting and they have used consultants from Denmark and the Netherlands in the establishment of the dairy production.

Many other emerging farmers we meet have similar city backgrounds and little experience of farming, and even less of organic farming.

Anatoly Nakaryakov, however, has more than three decades of organic experience, in Germany and Russia. He now heads the Savinskaya Niva organic farm with 5 800 hectares arable land and suckler cow production. The meat is sold to a baby food company as well as to outlets in Moscow. Almost half of it is sold on the conventional market however, a signal that marketing is still a challenge. They have exported some grain but Anatoly sees better use of the grain.

“I think of getting two thousand layer hens. There are no organic eggs in the Russian market.”

The farm is owned by Ekoniva, an agro-business corporation. Today, Savinskaya Niva in Kaluga is the only of Ekoniva’s operations which is organic; the other 355,000 hectares and +100,000 cattle are not organic.

Russian farms can, roughly, be divided into three categories

- Most of the land and about half of the value of production is in big agriculture enterprises. They are direct successors of the former collective and state farms. Some of these are owned by big agriculture holding companies such as Ekoniva. 150 such companies control 16 million hectares of land.

- Around 200,000 family farms or “peasants” have some 15 percent of the land and produce almost the same proportion of the output.

- Finally, more than 17 million households have small subsidiary plots for subsistence production and some sales (they are sometimes referred to as backyard farms). Despite that they cultivate only 4-5 percent of the land they are supposedly producing 35 percent of the agriculture output. This category of subsistence farmers were also common during Soviet times.

The government has promoted the establishment of the middle category of family farms (most of the government’s support goes to the large farms, however), and they are also able to benefit from the interest in local and organic, at least if they are located near a major city.

We eat another good meal at the restaurant Mark&Lev, located in the Tula region, 120 km from Moscow. It uses only locally sourced produce from small and mid-sized farms within a 150 km range. It is located in an area with many dachas, vacation homes.

“All those people bought their food in Moscow before coming here. It is a stupid idea to bring food to the countryside, food that no-one knows how it is produced and from where it comes. Meanwhile the farmers here could not reach the consumers so my idea was to connect them,” Alexander Goncharov, the owner of Mark&Lev and a former real estate developer, explains.

Lydia Vladimirovna Layutova in the village Peredavik, explains why she and her husband are cutting back on farming:

“We were real farmers earlier, but things were better then. It is more difficult with all the new rules introduced by the WTO membership, she says. Earlier there was a local slaughterhouse to which they could walk their cows, but this is long gone.”

| Lydia Vladimirovna Layutova in Peredavik |

I am not surprised that the government neglects these subsistence farmers, their contribution to the GDP and to the grand plans of the President is small. I am surprised, however, that they seem to be neglected also by the organic association. It seems to me to be a key group for the development of local, resilient and small scale organic farming.

Of course, I am not able to fully understand the situation of the subsistence farmers in Russia, and to what extent they do what they do as an active choice of lifestyle or because they have to (a distinction which may not be so clear as many people seem to believe). I also can’t judge how sustainable their production methods are (the pigs in the stable of Lydia Vladimirovna Layutova had no happy life). Nevertheless, I am intrigued by the opportunities that are found in such a self-sufficient local economy.