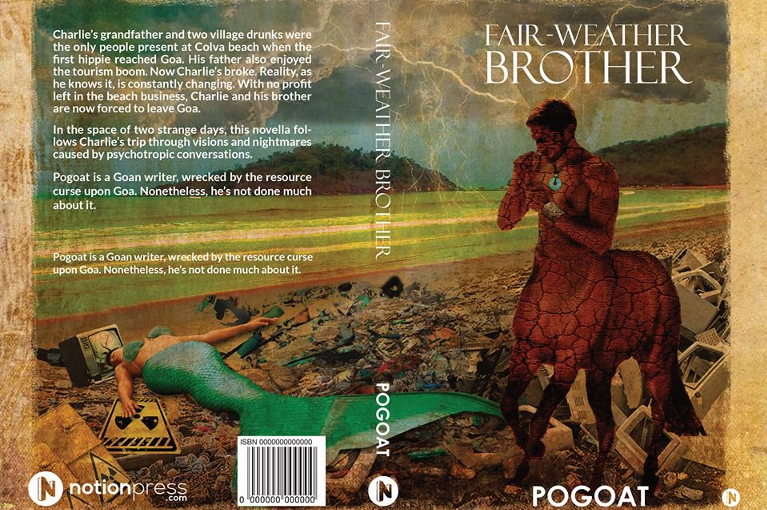

Fair-Weather Brother

By Pogoat

208 pp. Notion Press, Inc. – May 2018. $14.00.

Fair-Weather Brother is a portrait of the many environmental, economic and social challenges plaguing India today. The novella’s author, who goes by the pseudonym Pogoat, lives in India and thus knows of these issues firsthand. His book is about two financially strapped brothers who venture beyond their secluded beach hometown in search of opportunity elsewhere. Over a two-day period, they travel across a large swath of the country, taking us, in the process, through a montage of modern India’s ills.

The brothers, 30-year-old twins Charlie and James, operate a beach shack in the village of Colvá. The shack provides lodging to tourists visiting the white sand beaches of South Goa. The business has been in the family for three generations, and until recently has been quite lucrative. Now, however, business has slowed to a trickle. “People just don’t have money like they used to,” laments Charlie, our first-person narrator. The reason for his and James’ trip out of town is an interview that James has lined up in Bombay for a job as a cruise ship photographer, followed by a caretaking gig for both of them at a luxury campsite in the Himalayas. They plan to make this trip of more than 1,500 miles entirely by train.

The person alluded to in the book’s title is yet another brother named Inas. Charlie and James don’t much care for Inas, and they’re only reluctantly meeting up with him in Bombay because he is family and they happen to be passing through for James’ interview. Inas is known for being a hedonist, slacker, pathological liar and vicious betrayer with sociopathic tendencies. (This latter trait makes him perfectly suited to his job as a debt collector.) Now Inas is trying to persuade Charlie and James to lease their land to a casino company, against their grandfather’s wish that they never sell out to anyone.

But first he has a more immediate proposition for them. It happens to be a Friday, and, consummate partier that he is, Inas can’t resist going to a rave. Charlie and James both loath the thought of going anywhere with Inas, and they have an easy out. They need to get back on their train to continue on their northward journey. But Inas says he has more than enough air miles to fly the lot of them to Delhi, the train’s next stop. They’ll leave as soon as James gets out of his interview and then, once in Delhi, find a local rave to attend. Since the train doesn’t depart Delhi until 11 the next morning, they’ll have plenty of time to hop back aboard. Much to his own dismay, Charlie finds himself being manipulated into accepting this offer while James is away at his interview.

Charlie isn’t a city person, and so the whole time that he and James are being shown around Delhi by Inas and some of Inas’ friends, all he wants is to be back on his way to the mountains. By this point in the trip, he’s grown weary of the sight of rivers turned into sewage canals, smog so thick it looks like rain, plastic rubbish washed ashore from the ocean and mounds of putrid landfill trash. He feels deeply for the beggar children he sees working the streets. When he tries to make conversation about these issues, it mostly falls on deaf ears.

The travelers have trouble making the final leg of their trip—from Delhi to Nubra Valley—due to a sudden oil shortage that cripples transportation throughout the country. It all starts with a slew of terrorist attacks on oil rigs in the Middle East. Soon there are widespread power shortages and transportation systems grind to a halt. The Indian president comes on the radio to reassure the public and announce the implementation of an emergency protocol that will include strict fuel rationing. One can find plenty of echoes here of the real-life oil shocks of the 1970s.

Each of the settings depicted in this novella has its own set of dilemmas. The beach communities of South Goa face not only the decline of their tourist economy, but also the specter of radioactive contamination from a nearby nuclear power plant. Bombay and Delhi struggle with sprawl, congestion, sanitation, pollution and homelessness. And in the hilly countryside outside Delhi, many farmers are making the disastrous decision to grow jatropha—a poisonous shrub whose seeds are valuable as a motor fuel feedstock—at the expense of food crops.

The economic sea change that has occurred across much of the industrial world in recent decades is an especially poignant theme of this book. Charlie recounts how the same beach shack that he and James are struggling to keep afloat was an effortless bonanza for their grandfather, who came of age during a time of ever-increasing prosperity. When their grandfather was in his youth, hordes of people from all over the world could afford to vacation at Goan beaches every year—and to spend extravagantly while there. Their grandfather realized how lucky he was to have lived when he did. He would often tell his grandsons that they would never “enjoy an easy life” like he had. The family business, in his words, “just happened” without him having to do anything.

Perhaps the most intriguing twist to this story is that its weightiest themes are debated by people under the influence of psychotropic substances. As Charlie begins talking philosophy with the few people he meets who are of like mind with him, they do so while smoking joints and partaking of other drugs. In an especially pointed moment, one of Charlie’s new acquaintances points out how absurd it is that people like them are looked down upon as drug addicts by society at large, when those in the uppermost social strata have an addiction with vastly more detrimental consequences. These elites, says Charlie’s companion, are “burning up the planet and overdosing on profit!”

Our main characters speak in a distinctive-sounding dialect that is intended, according to Pogoat, to reflect how English is spoken between Indians within India. Though I can’t claim any firsthand knowledge of Indian speech, the dialogue certainly seems to me to have a ring of authenticity. The characters often address one another by monikers like “baba” and “machaa.” They add discourse markers like “re” and “da” to the ends of words and in between words. Sometimes they talk in Hindi, India’s other official language. (At such points, the narrator does non-Hindi-speaking readers a favor by translating into English.) There are also a few Portuguese words scattered about, in keeping with Goa’s many Portuguese influences.

Pogoat says this book is intended to be the first part in a trilogy. I’m captivated by its vivid depiction of India in this age of ecological limits, and I certainly plan to give any future installments a read.