FROM NUTRITIONISM TO CITY- AND PEOPLE-CENTERED FOOD POLICY

This is the first year that North America’s leading watchdog group on nutrition, Center for Science in the Public Interest, is not helmed by Michael Jacobson.

Jacobson has been a thorn in the side of the junkfood industry since 1971. Indeed, he coined such everyday terms as junk food, heart attack on a plate, and liquid sugar (soda pop). The food industry gave him worse than it got, and cast Jacobson as Nanny-in-chief, the Grinch who threatened to take the fun out of eating.

Now Jacobson has retired. The occasion prompted lavish praise from leading publications. (See here and here, for example).

Jacobson will be remembered for his hard-hitting campaigns against high-fat, high-salt and high-sugar foods.

Jacobson also deserves respect for his three game-changing contributions to our understanding of food. Each contribution deserves to become every bit as much a part of our everyday language as “junk food” and “heart attack on a plate.”

These contributions remain as controversial as when Jacobson put the words right in his organization’s name.

THREE GAME-CHANGING IDEAS

The first pivotal idea is that science should intentionally serve the public interest — not corporate interests, or government interests, or the institutional interests of Big Science.

The second pivotal idea is that food is fundamentally a public interest issue.

Most people automatically see topics such as education, public safety, housing, energy, transportation and the environment as issues of the national and public interest.

That used to be equally automatic with food, for both governments and individuals. Until the mid-1950s, when the term “agribusiness” was coined. Since then food has been first and foremost about the food industry and consumer choice — not public well-being or a citizen choice.

Understanding food as a public interest issue, Jacobson logically fought for the same tools as citizens have in their relations with any agency of a public good.

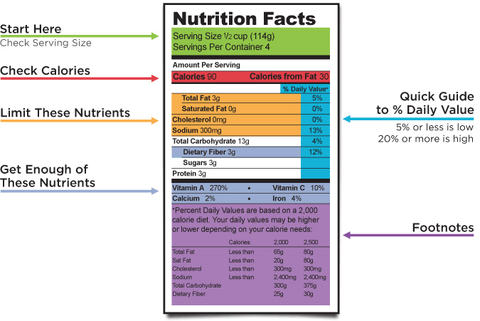

The third pivotal idea is that citizens and consumers have a right to basic information about the food they eat.

A committed factivist, Jacobson fought for the public’s right to know — specifically to know what ingredients were in the food that people put into their bodies. That information enables responsible decisions as to personal and society-wide health and well-being.

Jacobson and his supporters won many campaigns for fuller information. But their public interest claim has yet to be understood.

PARTIAL DISCLOSURE

Many people, and almost all food businesses, believe there’s no real need for full disclosure of information unless the product is under suspicion. We didn’t get calories on labels until obesity became a dead-serious problem. We still don’t have full (tobacco labels are an example of what it means to have full information and warnings) information and warnings on critical products such as alcohol and sugar. Nor is there labeling to let veggies and fruit tell their stories of pesticides and labor exploitation, let alone specific nutrients.

Because food is not seen as a public interest issue, the industry’s and government’s default position is that full knowledge is not a public right — until it’s established that the information is needed to solve a life-threatening problem, such as obesity or drinking when pregnant. Additives are innocent until proven guilty. As a result, every advance in public information has been hard-fought.

Jacobson put the issue front and center in his organizational title — the public interest

Jacobson fought the good fight on all three of these pivotal food issues.

Nevertheless, his retirement marks the end of an era in public interest food policy.

Jacobson’s understanding of food was set in terms of the assumptions now referred to as “nutritionism.” This ideology about food developed during World War 11, when the nutrition of soldiers and civilians was deemed essential to the strength, endurance and stamina needed to fight a war.

As neatly summarized in Wikipedia, the term nutritionism was coined by scholar Gyorgy Scrinis and later popularized by journalist Michael Pollan, who denounced it in his best-selling manifesto on food.

NUTRITIONISM

My own contribution to that discussion is laid out in my book, The No Nonsense Guide to World Food. That’s where I position nutritionism as a pillar of post-war Modernist ideology — the same ideology that brought us apartment towers, super-highways, plastic, chemical pesticides, and other commonplaces of industrialized and instrumentalized relations to life and living.

As a window on food, nutritionism presented food almost exclusively in terms of its nutrients or lack thereof. Jacobson rarely wandered far from nutritional preoccupations. The Center’s magazine, Nutrition Action, barely touched such topics as social determinants of health, food security, the farm crisis, animal welfare, genetic engineering, pesticides, food waste, urban agriculture, the social or cultural sides of food, the placeness, identity and spirituality of food relationships, the local or food sovereignty angles on food, the health or environmental impacts of pesticides, jobs in the food sector, or sustainability challenges raised by food. The one non-nutrition issue the magazine incorporated was exercize, an issue which it covered very well.

A tight focus on nutrition regulation led to a factivist style of politics. Jacobson’s work relied heavily on expert testimony presented to government authorities in national capitols such as Washington and Ottawa. It did not lead to movement building or to action at the local level.

Moreover, Jacobson’s Center stayed tethered to a confining understanding of food knowledge. Jacobson trained as a science professional, and earned a PhD in microbiology. The information sources and authorities he relied on were mostly limited to conventional science. There was little openness to other forms of knowing (Indigenous peoples’ knowledge, for example), and little engagement of experts without pedigrees linked to nutrition science.

SHIFT TO THE CITY

Starting in the late 1990s, Time started to pass nutritionism by. The modern food movement crystallized around 2007, when the Oxford dictionary declared “locavore” word of the year. After that, “healthfood nut” and “gourmet” were no longer the only words used to describe people who took food seriously. The very issues that didn’t square with nutritionism became the stuff of the New Food Equation (to use the phrase of Kevin Morgan and his colleagues at Cardiff University in Wales) which millennials embraced after the earth-shaking price hikes and food insecurity rebellions of 2008.

City food advocates and champions of local food policy councils took it upon themselves to break free from the ideology of nutritionism.

People who live in cities have city food needs, over and above their need for nutrition. Those city needs are is not based on the fact that people in cities need to eat to survive. Just as all individuals need food to survive and thrive with physical and mental health, cities need food to survive and thrive as vibrant physical, social, economic and cultural places. Nutritionism actually held cities back from recognizing their specific and essential civic interest in food.

All these added food dimensions highlight the public policy relevance of food. Food is not only a personal determinant of health. It deserves to be ranked as a social determinant of health — an idea that has not yet been accepted, in large part because of the hold nutritionism maintains in public health circles.

By the same token, all these added food dimensions earn food the stature to be classified among priority city issues. Realization of food as a city issue depends on realizing food as a public policy project, and on realizing that food is quintessential to city functioning.

In my own view, the self-conscious project of city food policy might be dated to the Food and Hunger Action Committee (FAHAC), set up by the newly-amalgamated metropolis of Toronto around the turn of the century. FAHAC (which I was staff co-lead for) presented three reports and a food charter to Toronto City Council during 2000 and 2001.

Shortly after the FAHAC reports and Food Charter were unanimously adopted by City Council, I wrote a critique of a draft of the city’s proposed Official Plan, which all but ignored food issues. My critique, called The Way to a City’s Heart is Through its Stomach, was stridently polemical, I’m embarrassed to say, and threw down the gauntlet on city planners as a group.

Fortunately for me and my development as a policy advocate, the critique was promoted by seminal food planning thinker Jerry Kaufman. This led to a dialogue with such Kaufman students as Martin Bailkey, Kami Pothukuchi and Samina Raja. That collaboration also included planner and urban agriculture specialist, Joe Nasr. With Kaufman’s help, we were able to spread our wings and spread our thoughts to a new generation of food and city enthusiasts. (For an academic review of this evolution, see Alison Blay Palmer, another leader of this transformation in food thinking.)

Food activism also veered toward “actionism,” not lobbying. Food groups are more likely to be found in community gardens or school meals or at farmers markets than in legislative hallways. Such actionism expresses an enthusiasm to be and to create the change you want to see, a hallmark of post-nutritionist food thinking.

I think the deep background reason for this difference is that followers of nutritionism ascribe sole health-creating power to the nutrients in the food, and therefore feel entitled to use social engineering techniques (taxes on “bad” foods, and so on) to drive people to make good food choices. By comparison, people-centered food policy links healthfulnness of food to the nutrients in the food, the conditions in which it was grown, the post-harvest handling methods and distance it traveled and the sociability and support of the dinner table. All such factors require more than a tax on bad foods. They require a food culture that, among other things, empowers and nurtures people.

I took a crack at writing about food as an empowering city and actionist issue in an e-book called Food for City Building, published by Hypenotic in 2014.

My thinking has continued to shift, partly in co-evolution with Barry Martin, creative director with Hypenotic, a Toronto-based communications firm. Our mantra became “We must ask what cities can do for food, but also, what food can do for cities.”

I now refer to the thinking that flows from putting food and cities together in that way as “people-centered food policy.” (Some of my writing about this is here and here.)

There has to be some division of government powers with regard to food. The old Catholic social doctrine of subsidiarity, now widely accepted within the European Union, offers us some guidelines on where cities and other local governments fit on a to-do and must-do list.

SUBSIDIARITY

Power should be “as low as possible and as high as necessary,” the subsidiarity guideline holds. That guideline suggests that “senior” levels of government have the resources, capabilities and needs to deal with Big Ticket items such as agriculture, fisheries, nutrition, and the like.

Local authorities, by contrast, are seen as having the resources, capabilities and needs to develop policies that come from the line of vision of everyday people issues.

Food fits that bill perfectly. Food can’t help but have an impact on such people issues as jobs and living wages, neighborhood cohesion, neighborhood rejuvenation, public safety, mental health, conviviality, the need for popular hangouts and “third places,” immigrant welcoming, multiculturalism and interculturalism, priority food neighborhoods (formerly called food deserts), community gardens, pedestrian and friendly main streets, farmers markets, school gardens. And those are all issues that cities have to deal with. The dovetailing of people issues and local governments couldn’t be better.

But just as cities and their residents started becoming more aware of the stuff of a city food agenda, they also became aware of how few national and international issues were being taken up by senior levels of government — the level of government that enjoys most and easiest access to taxes and other revenues.

The already-lengthy list of local and city to-do’s has been under pressure to expand because of an ideological force that began exerting itself later in Jacobson’s career — once the taboos of neo-liberalism took hold among national governments.

CITIES STEP UP TO THE PLATE

There’s a point when child neglect becomes child abuse, and a point where government neglect amounts to government abuse. The list of neglected food issues indicates that senior governments have crossed the line.

The list of questions senior governments leave unanswered is daunting. Who will protect antibiotics from dilution and overuse on factory barns? Who will protect the climate from global warming emissions arising out of long-distance food supply chains and factory-farmed meat? Who will protect local food supplies from emergencies when trade deals sanction corporate out-sourcing of food production and processing? Who will protect children from chronic diseases linked to degraded food ingredients? Who will protect people on low income and seniors from food insecurity?

In the absence of action from the governments furthest from them, citizens are looking to the governments closest to them. That’s why issues such as city taxation of soda pop have come to the fore. No other level of government will take on the junkfood industry.

The clearest expression of this transformation in jurisdictional thinking about cities and food is the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, adopted in 2015, and already signed onto by 161 cities around the world.

The two distinct impulses — the people-centered list of civic food needs, as well as the neglected issues city governments feel called on to do their part — mean that cities will increasingly be where the food action of the future takes place.

Jacobson’s key issue — the need for science-based nutrition policy in the public interest — will find its place alongside the people-centered food issues brought to the fore in the wide world of cities.

And we will long have Michael Jacobson to thank for his pioneering work in establishing food as a priority of public policy.

(If you like this post, please give me a clap, follow my blog (top, right), and check out my newsletter on food and cities at http://bit.ly/OpportunCity)