Contents

Introduction: the resurgence of New Green Deals.

Green Deals, Growth and Material Flows

Paying for a Green Deal: monetary flows.

Introduction: the resurgence of New Green Deals.

With increasing momentum, the idea of a New Green Deal (or Green New Deal) has entered the mainstream of progressive political debate. While a group of British economists and campaigners promoted the idea more than ten years ago2, it didn’t take off then. Now, however, the seriousness of, and public attention to, the climate emergency has helped to revive the idea: an ambitious transformative programme is needed to decarbonise the global economy, not least in the rich countries. Almost simultaneously, a similar set of policy proposals have emerged in several places, including in the USA, with the (New) Green New Deal3 proposed by leftists in the Democratic Party (the “Justice Democrats”4) and adopted by some of the prospective presidential candidates, in the UK, with the Labour Party’s Green Transformation paper5, in Spain, with the PSOE’s Transformación Ecológica6, and in the programme of Yannis Varoufakis’s pan-EU party DIEM 25. These all share the idea of investing in the rapid decarbonisation of the economy, creating “green jobs” in sectors such as renewable energy and housing retrofit, and offering a Just Transition for workers in those industrial sectors (predominantly fossil fuels) that will have to be closed down and replaced.

However, these policy frameworks all have shortcomings: none is, as yet, sufficiently detailed, each leaves significant gaps in the areas that have to be addressed, and all are promoted by parties that have yet to gain power or (in the Spanish case, with a challenging general election imminent) regain it. Rather than go into detail about the precise content of such programmes, I want to identify two areas of uncertainty that any Green Deal will have to address: controlling overall material flows and financing the transformation. Both these issues raise a key question, is a Keynesian model7 adequate to the challenge?

Green Deals, Growth and Material Flows

Proposals for Green Deals vary in how much they discuss the growth of the economy. The original UK proposal makes little mention of GDP growth except to criticise the concept, yet the following passage would seem to implicitly acknowledge that the investment in the clean economy, would, through the multiplier effect, cause an expansion of overall economic activity, alias GDP growth.

“This government intervention generates employment, income and saving, and associated tax revenues repay the exchequer. This is the multiplier process, attributed to Richard Kahn, Keynes’s closest follower.

Any public spending should be targeted so that domestic companies benefit, and then the wages generated create further spending on consumer goods and services. So combined heat-and-power initiatives generate income for construction and technological companies, and then workers’ salaries are spent on food, clothes, home entertainment, the theatre and so on, creating demand for those industries.”8

This is the crux of the problem: investing in, and expanding the clean, the good, sectors of the economy is a specific intervention but it has non-specific consequences, spilling over into the expansion of the dirty and the bad sectors.

It is interesting that the proposal for the Green New Deal tabled by Alexandria Ocasio-Córtez doesn’t once mention economic or GDP growth. However, not surprisingly, given its evocation of Roosevelt’s New Deal, the idea is there implicitly (see my emphasis in the following quotation).

“…a new national, social, industrial, and economic mobilization on a scale not seen since World War II and the New Deal era is a historic opportunity—

(1) to create millions of good, high-wage jobs in the United States;

(2) to provide unprecedented levels of prosperity and economic security for all people of the United States; and

(3) to counteract systemic injustices ……“It is the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal—

(A) to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions through a fair and just transition for all communities and workers;

(B) to create millions of good, high-wage jobs and ensure prosperity and economic security for all people of the United States…”

It also mentions that investments will “spur economic development” ……and calls for

“enacting and enforcing trade rules, procurement standards, and border adjustments with strong labor and environmental protections—

(i) to stop the transfer of jobs and pollution overseas; and

(ii) to grow domestic manufacturing in the United States…”9

Other advocates of the Green New Deal are more explicit in embracing continued GDP growth. In a 2018 article in New Left Review, Robert Pollin calls for Green Growth, that will both require and cause expansion of the economy, measured via GDP. His article is explicit in its critique of degrowth and the idea of constraining the scale of the economy10.

As Robinson Meyer notes in an article in Atlantic magazine11, a prominent influencer for Green Deal thinking has been Mariana Mazzucato. Mazzucato’s almost single emphasis has been on the historical role of State investments in facilitating industrial and technological innovation. Her unit at University College London has produced a briefing paper on the New Green Deal and again adjectival GDP growth (green growth, inclusive growth) is a central assumption12. Mazzucato is one of a number of broadly post-Keynesian economists who have been influential, formally or informally on the UK Labour party’s economic policy. While Britain’s Green Transformation hardly mentions economic growth, the term crops up like a mantra in other Labour policy statements13.

The evidence is clear enough on “Green Growth”. Increases in the scale of the economy are associated with increases in the throughput of energy and materials. Green growth would require the decoupling of growth in the size of the economy (conventionally GDP but effectively the sum of exchange value) from the increase in material flows. In the case of carbon emissions, there is limited evidence that for some OECD economies this has been achieved for some years, but there are uncertainties in the data and its interpretation14, and when international shipping and aviation plus embodied carbon in imports is taken into account, the evidence of any decrease in emissions is slim15, so the decoupling has been only relative (increased efficiency not keeping pace with increased flows), or at best, barely absolute: insufficient to deliver the enormous cuts required, some 15% p.a. for a conurbation such as Greater Manchester. For other material flows, the evidence is that there is no decoupling16. Consider what this means: for each increment in the scale of the economy, there is an increment in the extraction of minerals, the number of mines, the extent of cultivated land, the extraction of water, the number of ships, lorries and planes carrying goods and people, and in the amount of waste that has to be disposed of, whether by recycling or dumping in the earth’s land, sea and air, its ecological sinks. As George Monbiot recently put it,

“What we see is not the economy. What we see is the tiny fragment of economic life we are supposed to see: the products and services we buy. The rest – the mines, plantations, factories and dumps required to deliver and remove them – are kept as far from our minds as possible. Given the scale of global extraction and waste disposal, it is a remarkable feat of perception management.”17

When that reality is continually expanded, then we have precisely the problem that the Green New Deal, and Green Growth is supposed to solve. Now it will be argued that things will be different from now on: the New Green Deal is precisely the unprecedented transformation that will ramp up the decarbonisation of the economy. It is indeed true that a major transformation is required, on the kind of scale of the Marshall Plan reconstruction of war devastated Europe or of China’s conversion into a manufacturing power-house. Clearly, there is a need for huge investment in transformation, for example in the decarbonisation of the power grid, the conversion of transport, heating and manufacture to electric power, and massive increases in energy efficiency. But four problems have to be addressed, as part and parcel of any realistic New Deal.

1) The inherent constraints of renewable energy. So far, increases in renewable energy deployment have not led to a reduction in fossil fuel usage globally. Overall their deployment has been essentially to add to the global energy mix rather than replacing fossil fuels. Moreover, it is doubtful whether renewables can provide the scale of concentrated energy used by the current global economy: the constraints are less in the power that could theoretically be generated from natural flows than in the minerals needed to deploy them: minerals used in generators and motors, in batteries and in electronics, as well as copper for transmission of power18. These are finite and with limited substitutability. The revolution will be low powered, so the Green Deal has to factor in a plan for energy descent.

2) Control of the non-specific growth of the economy. As noted above, the multiplier creates a problem, in that the desired growth of the economy also calls forth undesirable growth. That is unless the expansion of commodities is controlled. It means a series of measures to constrain the manufacture of false desires through the marketing and sales operation of modern capitalism. More than this, it means imposing caps on resource and energy use. There are several proposals for how to do this, from what is essentially a consumption tax based on financial transactions, suggested by Richard Murphy19, one of the authors of the 2008 British New Green Deal, to the kind of Cap and Share scheme promoted by the Irish NGO FEASTA20. An ecologically feasible Green Deal would involve resource and energy caps, at source, effectively the equitable rationing of commodities (goods and services). Doing this would also incentivise the transition to less ecologically and resource intense offerings across the market, so long as emitting activities are not thereby driven underground.

3) Dealing with the non-energy constraints on growth. The non-energy constraints on renewables deployment have already been mentioned. Similar considerations apply to the economy in general. This is the finding of the Limits to Growth study which indicated that as resources become scarcer, their cost increases, undermining the stability of the production system21. Any expanding economic system has to grapple with this, even if it successfully exploits essentially free natural energy flows: you can’t create minerals from sunlight. These economic consequences of the increasing scarcity and inaccessibility of most minerals and metals need to be addressed in any credible Green Deal, yet there is almost no discussion of this crucial reality in any of the proposals, nor of the ‘hidden’ resource intensive activities of new technology.

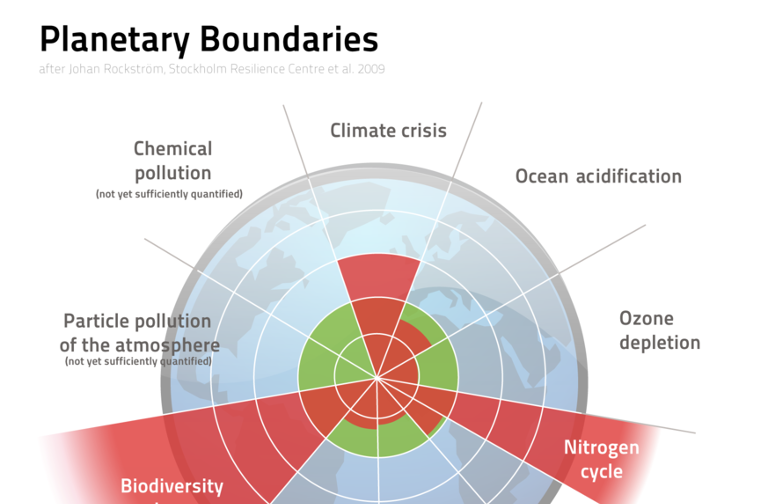

4) Dealing with the non-climate consequences of economic expansion. Even if it were possible to mitigate the climate crisis through the kind of transformation proposed in the various Green Deals, there are other ecological crises to contend with. These can be understood in terms of the Planetary Boundaries framework proposed by Johan Rockstrröm and colleagues22. One of the boundaries is climate change, but this is just one. The others are, Ocean acidification, Stratospheric ozone depletion, Atmospheric aerosol loading, Biogeo-chemical flows (interference with Phosphorous and Nitrogen cycles, Global freshwater use, Land system change, Biodiversity loss, and Chemical pollution. As of 2015, the evidence available to the Planetary Boundaries investigators indicated that

“Four of nine planetary boundaries have now been crossed as a result of human activity:… climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, land-system change, altered biogeochemical cycles (phosphorus and nitrogen).

Two of these, climate change and biosphere integrity, are what the scientists call ‘core boundaries’. Significantly altering either of these “core boundaries” would “drive the Earth System into a new state”

Transgressing a boundary increases the risk that human activities could inadvertently drive the Earth System into a much less hospitable state, damaging efforts to reduce poverty and leading to a deterioration of human wellbeing in many parts of the world, including wealthy countries…”

It is unclear whether and how the various Green Deals propose to address these additional threats, especially if they rely on the notion of green growth.

Paying for a Green Deal: monetary flows.

Assuming, as I do, that some kind of a Green Deal is desirable (provided that it can address the material flow issues reviewed in the previous section), then how is it to be paid for?

The 2008 UK New Green Deal proposal was explicit about this. Its great strength was the integration of climate change, peak oil and the financial crash. It changed my thinking. To paraphrase Kant, it woke me from my siloed slumbers, indicating the need to connect spheres that I had hitherto regarded separately. It suggested a combination of measures:

1) Government funding: “in part from the increase in the Treasury’s coffers from rapidly rising carbon taxes and carbon trading” and “a windfall tax on oil and gas companies”.

2) Private sector funds: “Public funding could be augmented by encouraging the use of private savings from individuals, pension funds, banks and other savings vehicles”.

3) Private investment in government bonds: “… citizens and institutional investors can provide funding for the Green New Deal include investment in ‘green gilts’ (government bonds), guaranteed not just in terms of an interest rate, but also in terms of their use to reduce carbon.”

4) Redirection of current savings and investments: “There is a wall of money in pensions and other savings, plus a recognised need by the Government for people to save much more. Guaranteed investments via a Green New Deal programme will help provide the upfront funding needed for the low-carbon future.

“Local authority bonds could be the major vehicle for the funds raised for this programme. … this source of funding, and local democracy, could be promoted relatively easily if the returns on the money saved from the low-carbon investments, minus their cost, were used to repay such bonds. …. Local authority bonds could be an investment route for pension funds and even individual savings to help fund such a crash programme. …… it seems a reasonable supposition that for the private sector, clean technology is going to be a relative safe haven.”

And these investments will realise their return from net savings from the transition: “It is the cost savings from moving out of intensive fossil fuel use, minus the cost of implementing energy-saving and clean-energy infrastructure, which will fund the repayment of loans made under the Green New Deal.”

This seems a reasonable set of proposals, at least within the terms of the capitalist system. Government and private sector will raise credit from other sectors of the economy, including individual and corporate investors, including public and private sector pension funds. These investors and savers will realise a return via dividends and interest, funded by the net saving from the energy transition23 (assuming of course that there will be a net saving, and this is not a foregone conclusion). Since private venture capital tends to seek relatively short term returns, the State-brokered forms of “patient capital” are likely to be more important24. Essentially this relies on the value generated from harnessing free flows of natural energy (renewables) in substitution for the value generated from monopolised stock energy (i.e. fossil fuels reserves). The nature of this “value” will be returned to.

However, other commentators have suggested alternative funding sources, typically drawing on another variant of post-Keynesian thinking, Modern Monetary Theory. Ocasio Córtez released a FAQ25 with the legislative proposal. The original version included links to two articles, that set out the MMT thinking. The most significant of these was by leading MMT academic Stephanie Kelton and colleagues26. It explained that governments never have to raise money before spending. Instead they spend, thereby creating money, and that money is re-couped from the economy later, as taxes, essentially a portion of the economic growth so generated. Interestingly, Ocasio Córtez’s team withdrew the original version of the FAQ, replacing it with a version that left out these MMT links27. There were political reasons for this that need not concern us here. What is interesting is the question as to whether MMT, or crudely, the government printing money, is necessary.

The question of how Green Deals (and indeed other policy alternatives that end austerity) should be funded has also been debated in Britain too. Richard Murphy, another of the 2008 Green Deal’s authors has proposed People’s Quantitative Easing28, an idea in that Jeremy Corbyn initially endorsed in his first leadership election. It is not unlike the concept of Green Quantitative Easing proposed by Green Party economists Victor Anderson and Molly Scot-Cato29. The chartalist NGO, Positive Money, are keen on this family of ideas and have produced a helpful comparative guide to them30. However, Murphy himself has also stated that MMT is not necessary for the New Green Deal31. Ann Pettifor has argued against these approaches in her book, the Production of Money32, arguing like Wren Lewis, and it seems also McDonnell now, for more conventional government borrowing.

The Marxist economist blogger Michael Roberts has, in a series of three pieces, dissected MMT33. He points to the similarities between MMT and Marx’s understanding of money creation in the capitalist economy, but highlights the essential difference: exchange value is created in the labour process (by the exploitation of labour, the taking of surplus value by the capitalist) and not by the creation of money. Bankers, capitalists and governments can create money, as credit, and do so but if that money is to have exchange value, it has to be underpinned (sooner or later) by value creation in the labour process34. Credit is no more than a promissory note for expected surplus value. Paul Mason explains the problem like this:

For many people on the radical left, MMT has become a new panacea – a get-out-of-jail free card for Keynesian economics in a world of highly indebted and stagnant capitalism. Unfortunately, it is not.

While it’s true there is a lot more tax and spend capacity in a modern economy than the free-marketeers admit, it is not infinite. Nor is it possible to infinitely expand the money supply without collapsing the value of money towards zero. MMT gives no account of where economic growth or profit comes from other than within the monetary system itself. Unlike Marxists, who believe value is created in the production process, the MMT crowd believe it can be created by the interplay of fiscal and monetary policy.35

But luckily, Green Deals do not require this kind of large-scale creation of money by governments. Roberts puts it like this36:

“Actually, it is not necessary to adopt MMT to deliver the GND programme. There are many ways to meet the bill. First, there is the redistribution of existing federal and state spending in the US. Military and defense spending in the US is nearly $700bn a year, or around 3.5% of current US GDP. If this was diverted into civil investment projects for climate change and the environment, and those working in the armaments sector used their skills for such projects, then it would go a long way to meeting GND aspirations. Of course, such a switch would incur the wrath of the military, financial and industrial complex and could not be implemented without curbing their political power.

“Then there is the redistribution of income and wealth through progressive taxation to raise revenues for extra public spending on the needs of the many.

“… it will be an illusion to think the GND can be implemented, even in just economic terms, simply by following MMT and printing the dollars required. Yes, the state can print as much as it wants, but the value of each dollar in delivering productive assets is not in the control of the state where the capitalist mode of production dominates. What happens when profits drop and a capitalist sector investment slump ensues? Growth and inflation still depends on the decisions of capital, not the state. If the former don’t invest (and they will require that it be profitable), then state spending will be insufficient.”

But Roberts then goes on to argue that, under capitalism, only increased economic growth can finance the Green Deal, i.e. pay back the investment made. This is close to the position of the Green Growth advocates. This seems a reasonable position, within the parameters of capitalist growth economics. But is an alternative possible?

This is something that ecological economists need to focus on. There are some indications that,

-

The creation of credit can fund necessary investments without creating an imperative for economic growth.37

-

The redirection and re-prioritisation of undesirable economic activity could fund the necessary investments.38

But as we have seen, there are dangers in a Green Deal that does not deal with the material flows that are destroying the earth’s biophysical systems on which life depends. It will be necessary to design a green deal that

a) constrains material flows of the economy as a whole. This will prevent the necessary investments from creating unwanted multiplier damage, but it will constrain the economic growth (i.e. profits, based on expropriation of surplus value) that will recharge the public and private investments that have been made.

b) directs expenditure to the needed areas, without relying on unconstrained material growth of the economy to back it.

It is perhaps hard to see that happening within a capitalist system which, by definition is one founded on the self-expansion of capital, invisibly resting on labour exploitation39. As Lange concluded in his examination of the parameters of a successful economy without growth,

“Many of these policies stand in conflict with the interests of strong social groups. In particular, they contrast [with] the interests of the capitalist class …. or the oligarchy. These groups40 would lose major parts of economic wealth and income and the ability to accumulate capital.”41

It seems that once New Green Deals are seriously considered, in terms of material and monetary flows, then both degrowth and socialism of some sort42 come onto the agenda too. Both imply fundamental changes in culture, values, expectations and in our relationships with the wider globe, both its peoples and its natural systems.

___________________________________________________________

Notes.

1 Thanks to Peter Somerville, Carolyn Kagan and James Vandeventer for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

2 https://web.archive.org/web/20081223042632/http://www.neweconomics.org/gen/uploads/2ajogu45c1id4w55tofmpy5520072008172656.pdf

3 https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/109/text

4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Justice_Democrats

5 https://www.labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/The-Green-Transformation-.pdf

6 http://www.transicionecologica.es/index.php/category/documentos/documentos-capte/

7 That is, one based on government-led investment to stimulate demand in the economy.

8 https://web.archive.org/web/20081223042632/http://www.neweconomics.org/gen/uploads/2ajogu45c1id4w55tofmpy5520072008172656.pdfp. 27

9 https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/109/text My emphasis.

10 Pollin, R. (2018). De-Growth vs a Green New Deal. New Left Review, (112), 5–25. https://newleftreview.org/II/112/robert-pollin-de-growth-vs-a-green-new-deal#_ednref24

My own response to Pollin, with Peter Somerville, is in press in New Left review at the time of writing.

11 https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/02/green-new-deal-economic-principles/582943/

12 https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/sites/public-purpose/files/iipp-pb-04-the-green-new-deal-17-12-2018_0.pdf

13 See my blog pieces on Labour and the question of degrowth, indexed at https://uncommontater.net/2017/12/19/degrowth-divestment-politics/ and also my article, ‘Degrowth: the realistic alternative for Labour’, to appear later in 2019 in Renewal.

14 https://steadystatemanchester.net/2016/04/15/new-evidence-on-decoupling-carbon-emissions-from-gdp-growth-what-does-it-mean/

15 https://kevinanderson.info/blog/category/quick-comment/

16 Wiedmann, T. O., Schandl, H., Lenzen, M., Moran, D., Suh, S., West, J., & Kanemoto, K. (2015). The material footprint of nations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(20), 6271–6276. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1220362110

17 https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/30/worse-than-plastic-burning-tyres-india-george-monbiot See also Brand, U., & Wissen, M. (2018). The limits to capitalist nature: theorizing and overcoming the imperial mode of living. London ; New York: Rowman & Littlefield International.

18 García-Olivares, A. (2015) ‘Substitution of electricity and renewable materials for fossil fuels in a post-carbon economy’, Energies 8: 13308-13343. http://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/8/12/12371

19 Murphy, R. (2015). The joy of tax: how a fair tax system can create a better society. Bantam Press.

20 Davey, B. (Ed.). (2012). Sharing for Survival. Dublin: FEASTA.

Also see http://www.capandshare.org/features.html

21 Jackson, T., & Webster, R. (2016). LIMITS REVISITED A review of the limits to growth debate(p. 24). London: ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUP ON LIMITS TO GROWTH. Retrieved from http://limits2growth.org.uk/revisited

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens, W. W. (1974). The Limits to growth : a report for the Club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. London: Pan Books. Retrieved from http://www.donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Limits-to-Growth-digital-scan-version.pdf

Meadows, D. H., Randers, J., & Meadows, D. L. (2005). Limits to Growth : the 30-Year Update. London: Earthscan.

Turner, G. (2008). A comparison of The Limits to Growth with 30 years of reality. Global Environmental Change, 18(3), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.05.001

Turner, Graham. (2014). Is global collapse imminent? Melbourne: University of Melbourne. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267751719_Is_Global_Collapse_Imminent_An_Updated_Comparison_of_The_Limits_to_Growth_with_Historical_Data

Homer-Dixon, T., Walker, B., Biggs, R., Crépin, A.-S., Folke, C., Lambin, E. F., … Troell, M. (2015). Synchronous failure: the emerging causal architecture of global crisis. Ecology and Society, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07681-200306

22 Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F. S. I., Lambin, E., … Foley, J. (2009a). Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecology and Society, 14(2), no page number: digital journal. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03180-140232

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E. F., … Foley, J. A. (2009b). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461(7263), 472–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockstrom, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., … Sorlin, S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347(6223), 1259855–1259855. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855

23 This approach is reiterated by both Ann Pettifor, one of the authors of the 2008 Green Deal and by the Keynesian economist, Simon Wren Lewis

Pettifor, A. (2018, September 21). To Secure a Future, Britain Needs a Green New Deal. Retrieved 22 September 2018, from https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4045-to-secure-a-future-britain-needs-a-green-new-deal

Wren Lewis, S (2019). How to pay for the Green New Deal https://mainlymacro.blogspot.com/2019/02/how-to-pay-for-green-new-deal.html

24 Mazzucato, M., & McPherson, M. (2018, December). The Green New Deal: A bold mission-oriented approach. University College London. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/sites/public-purpose/files/iipp-pb-04-the-green-new-deal-17-12-2018_0.pdf

25 https://web.archive.org/web/20190207191119/https:/ocasio-cortez.house.gov/media/blog-posts/green-new-deal-faq

26 https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/opinion-green-new-deal-cost_us_5c0042b2e4b027f1097bda5b

27 https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/5729035/Green-New-Deal-FAQ.pdf

28 Initially proposed with Colin Hines, another 2008 Green Deal author, as Green Infrastructure QE: Murphy, R. (2015). ‘How Green Infrastructure Quantitative Easing Would Work’. Tax Research UK. Available at: http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2015/03/12/how-green-infrastructure-quantitative-easing-would-work/#sthash.wZqcTosl.dpuf

29 Anderson, V. (2015). ‘Green Money: Reclaiming Quantitative Easing’. The Green EFA group for European Parliament. Available at: http://mollymep.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Green-Money_ReclaimingQE_V.Anderson_June-2015.pdf

30 https://positivemoney.org/2016/04/our-new-guide-to-public-money-creation/

31 https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2019/02/18/does-the-green-new-deal-need-modern-monetary-theory/

32 Pettifor, A. (2017). The production of money: how to break the power of bankers. London: Verso.

33 https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2019/01/28/modern-monetary-theory-part-1-chartalism-and-marx/

34 S Mavroudeas and D Papadatos (2018). Is the financialization hypothesis a theoretical blind alley? World Review of Political Economy 9, (4).

35 https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/economy/2019/02/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-s-green-new-deal-radical-it-needs-be-credible-too

See also D Henwood, Modern Monetary Theory Isn’t fHelping, Jacobin. https://jacobinmag.com/2019/02/modern-monetary-theory-isnt-helping

36 https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2019/02/08/the-green-new-deal-and-changing-america/

37 Berg, M., Hartley, B., & Richters, O. (2015). A stock-flow consistent input–output model with applications to energy price shocks, interest rates, and heat emissions. New Journal of Physics, 17(1), 015011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/17/1/015011

Jackson, T., & Victor, P. A. (2015). Does credit create a ‘growth imperative’? A quasi-stationary economy with interest-bearing debt. Ecological Economics, 120, 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.09.009

Lee, K.-S., & Werner, R. A. (2018). Reconsidering Monetary Policy: An Empirical Examination of the Relationship Between Interest Rates and Nominal GDP Growth in the U.S., U.K., Germany and Japan. Ecological Economics, 146, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.08.013

This is a topic discussed in my critique of Positive Money’s proposals for “sovereign money” as a way of stemming the growth imperative. https://steadystatemanchester.net/2018/02/23/we-need-to-end-growth-dependency-but-how/

38 See the quotations above from the 2008 Green New Deal and from Roberts.

39 Not just accumulation of surplus value from waged workers but also on “primitive accumulation” from unpaid labour in the home, the pillaging of natural assets and commons, worldwide. See for example Moore, J. W. (2015). Capitalism in the web of life: ecology and the accumulation of capital (1st Edition). New York: Verso.; Moore, J. W. (n.d.). World accumulation & Planetary life, or, why capitalism will not survive until the ‘last tree is cut’. Retrieved 18 January 2018, from http://www.perc.org.uk/project_posts/world-accumulation-planetary-life-capitalism-will-not-survive-last-tree-cut/

40 Which also include institutional, collective investors, such as pension funds: in a green, equitable economy, there would have to be a different model of pensions from that based on stock market returns.

41 Lange, S. (2018). Macroeconomics without growth: sustainable economies in neoclassical, Keynesian and Marxian theories. Marburg: Metropolis-Verlag.

42 For me that is a socialism of the alternative, anti-productivist, tradition, seeking a fundamental escape from commodification of nature and labour, rather than a Statist way of running that process more benignly and effectively. See Burton, M. ‘Degrowth: the realistic alternative for Labour’, to appear later in 2019 in Renewal, or https://steadystatemanchester.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/labour-and-degrowth-text.pdf.