My previous post about farmers’ protest in Europe crticised free trade in food. Some people argue that this trade is needed to supply poor people in poor countries with food. “Food security rests on trade” by Angel Gurría, Secretary-General of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and José Graziano da Silva, Director-General of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is just but one example of this.

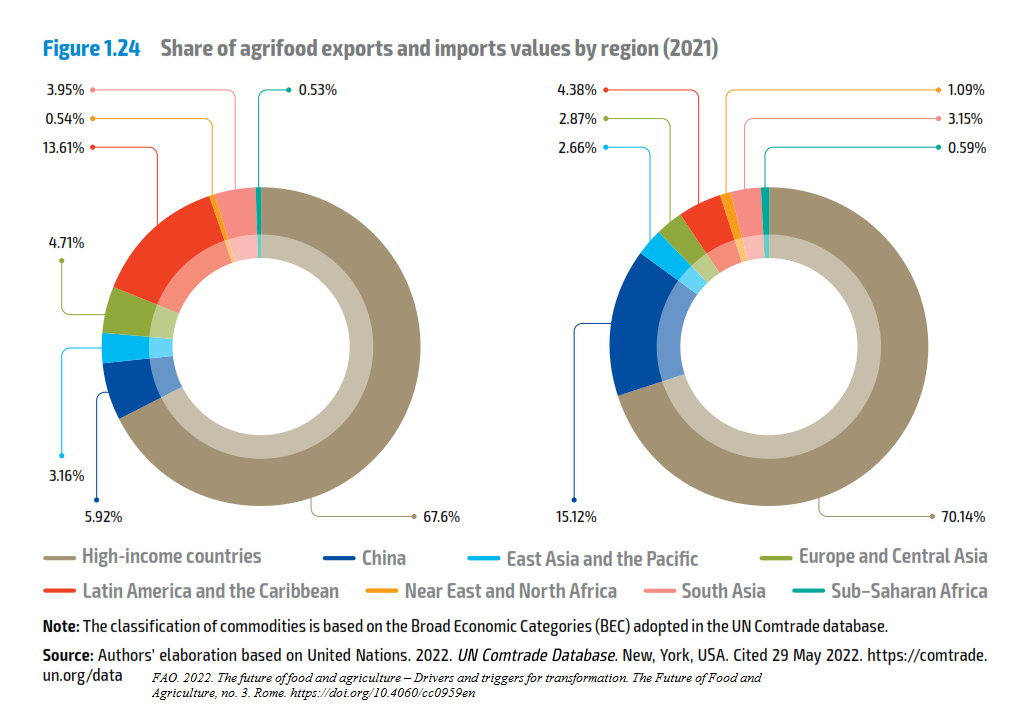

Clearly, there are situation when trade can alleviate short term food shortages caused by natural disasters, war or failed crops. But very little of the trade in food products is like that. Instead the overwhelming trade in food is between rich countries; more than 2/3 of the food imports and exports are to and from high-income countries. Sub-saharan Africa’s share of global food imports is less than 1 percent.

Even when we look at the rather small quantities that are imported to Africa the share of staple foods, i.e. food that would alleviate hunger, is rather low, instead most of the food is processed foods.

The basic argument in favor of “free trade” is that some countries or companies are better in producing some stuff than others and those that are best, i.e. most competitive, should produce it (there is a more delicate difference between having absolute or comparative advantage, but that doesn’t really change anything in this context).

It is quite clear that small-holder farmers in poor countries can’t produce staple foods like corn, rice or wheat to world market prices which are determined by the production costs of a limited number of exporters. If you want to understand why I compare the production of corn by Rob Stewart in USA with Susan Mkandawire in Zambia in this article.

Agriculture commodities markets are mostly also oversupplied, which means that prices are very low.

This leads to poor countries and poor farmers buying basic food commodities. The farmers either quit or have to re-orient themselves to higher value, labor intensive, export crops, such as cocoa, coffee, flowers, pineapples or avocadoes. This can be clearly visible in most developing countries. While this might be an economically reasonable “solution” in good conditions it is a risky situation when the terms of trade changes or when there are global disruptions in trade. This was apparent under the covid-19 pandemic. It is certainly not a resilient situation and it is in particular most risky for the poor. Rich people never starve…

Europe has let almost 100 million hectares of farm land revert to forest or lying idle, while European farmers buy soy from South America and European food industries buy palm oil from Malaysia and Indonesia. Europe could produce those, or equivalent crops, within its own territory, but it is simply cheaper to import it. Thus, trade has diminished the European production and created a trade dependency.

The higher proportion of food that is globally traded, the bigger dependencies will be created, when regions that could produce their own food cease to do that. More and more people will be structurally dependent on global trade; trade becomes its own justification.