It often feels as if the world is falling apart. In the past few years, we have faced a global pandemic, record high global temperatures, serious threats to democracy, and the rise of frightening technology — including social media and artificial intelligence. It is not surprising that people are burned out from existential panic.

The general malaise about these and other serious challenges is beautifully captured by several memes. Our favorite is the little dog in a hat saying “it’s fine” as the house burns down around him. If anything, we have developed a finely-tuned gallows humor about the state of the world.

But is this a useful stance to take in the face of these threats? Should we be yelling that the sky is falling at every chance? Or might that paralyze us into inaction, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy?

If we are all doomed, maybe it doesn’t matter if I skip my vaccination, buy a Hummer, and lie on my couch on election day. I’ll just post catastrophic memes for clicks on social media as the world burns around me. At least I’ll get a few dopamine hits before it’s all gone.

In fact, this is pretty much what we found in a massive new study that we published in Science Advances this month! To help figure out the precise impact of climate doomerism and compare it with alternative messages, we recently completed one of the largest experiments ever conducted on climate change behavior.

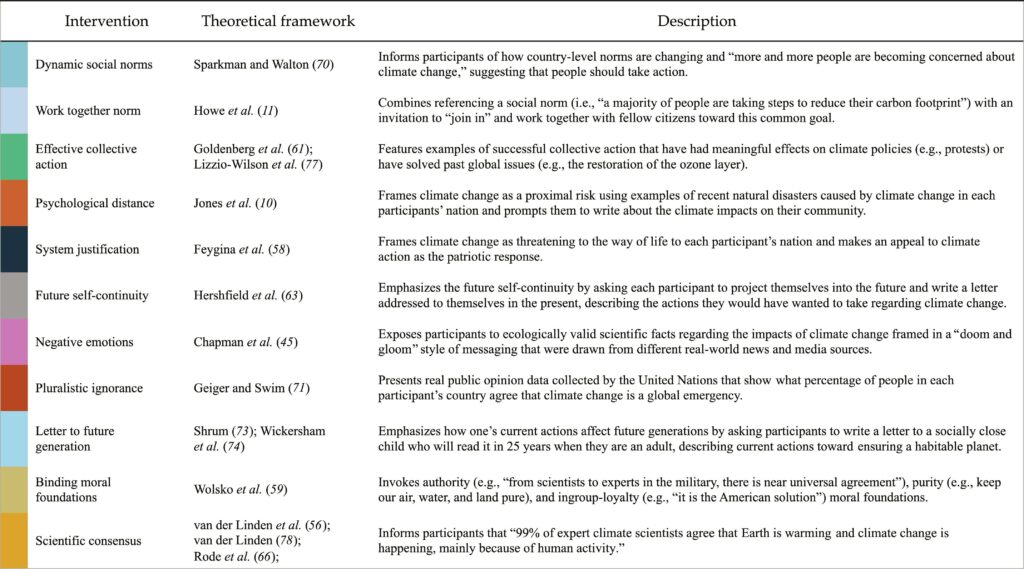

Together with an international team of 255 other behavioral scientists and climate change experts (led by Madalina Vlasceanu & Kim Doell), we tested the effects of the 11 common messages meant to boost climate change beliefs, policy support, and concrete action. These messages were selected by a team of experts, and we consulted with the scientists who had originally created and tested each message to ensure we got it right (you can see a summary of each intervention below).

The messages/interventions ranged from emphasizing scientific consensus (e.g., noting that “99 percent of expert climate scientists” agree on the climate change facts), or the widespread concern of others (e.g., a majority of people in each nation is concerned), to emphasizing the consequences for one’s region (e.g., increased frequency and severity of wildfires and floods) or the effects of climate change on future generations (e.g., asking participants to imagine writing a letter about their actions regarding climate change that would be read by people decades from now).

Click graphic for larger view.

Imagine how you would feel if you read this message (from the negative emotions intervention), which involved exposure to scientific claims about the impacts of climate change in a doom and gloom messaging style typically used by climate communicators to induce negative emotions:

“Climate change is happening much more quickly and will have a much greater impact than climate scientists previously thought, according to the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2022). If your anxiety about climate change is dominated by fears of starving polar bears, glaciers melting, and sea levels rising, you are barely scratching the surface of what terrors are possible, even within the lifetime of a young adult today. And yet the swelling seas—and the cities they will drown—have so dominated the picture of climate change/global warming that they have blinded us to other threats, many much closer at hand and much more catastrophic…”

Does this inspire you to take action or leave you feeling overwhelmed?

We compared this doom and gloom message to the other climate change messages on a highly diverse sample of over 59,440 participants. Since climate change is a truly global issue, we translated and tested these messages in 63 different countries. This allowed us to see which messages worked best around the globe—as well as within specific countries and cultures.

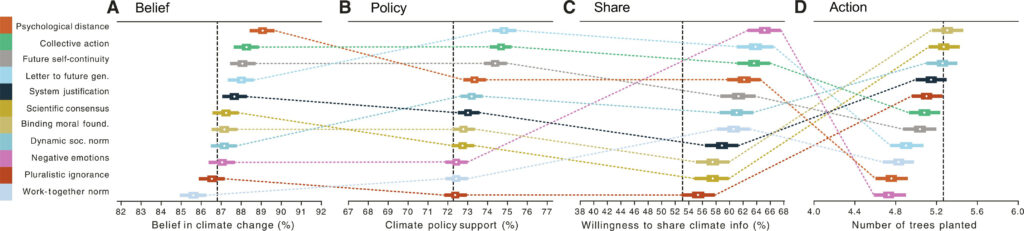

Our findings revealed that doom and gloom messaging was highly effective for stimulating climate change information sharing, like posting on the internet or social media, where negativity reigns. As you can see in our figure below, doomerism (ie negative emotions) was the single most effective strategy for increasing social media sharing.

However, doom and gloom messaging was the absolute worst for motivating action and among the worst for changing climate change beliefs or support for climate change policies. In fact, negative emotions backfired on effortful behavior—making people significantly less likely to take action for the environment compared to a neutral control condition (shown as the dotted line on the figure below).

Click graphic for a larger view.

It turns out that critics are right to worry that doom and gloom can demoralize the public into inaction. We found that this strategy had no effect on policy support or climate beliefs. For these outcomes, writing a letter to future generations explaining one’s climate actions today or thinking about the consequences of climate change in one’s region were the most effective interventions.

And doom and gloom even backfired when it came to more effortful behavior. When faced with the enormous stakes of the climate crisis, personal actions—and perhaps even policy change—can seem futile. People withdraw or disengage. As Madalina and Jay recently concluded in an article for Scientific American:

“Doom and gloom messaging can do both things: induce helplessness, discourage individual-level action; but also motivate people to spread the word.”

Many other messages also failed or even backfired, underscoring how difficult it is to actually mobilize real, effortful action on climate change. This is why far more research is needed on the topic and why we all need to embrace greater intellectual humility around this issue.

It’s common to see certain messages—and messaging strategies—go viral on social media. But that doesn’t mean they will work in the real world. In fact, they might even backfire. The norms and incentive structures of social media are very different from the real world. The messages that work online may be completely counterproductive offline. We need to keep this in mind when mobilizing real action.

We also found that different people responded differently to the various climate messages and that this varies across countries. To design the most effective messages, scientists and policy makers will need to tailor them to the right audience.

To see the effects of our interventions along dimensions such as country of residence, income level, age, ideological leaning, socioeconomic status, gender and also type of climate action targeted, visit our open-access user-friendly web app. Feel free to play around and find out what worked best (or worst) in your home country.

Sadly, we did not find a silver bullet for spurring climate action. But our research found several messages that moved the needle on climate change beliefs and actions. We suspect that similar lessons apply to other issues, from strengthening democracy to public health. In fact, we were recently part of a similar project designed to reduce affective polarization and found that several messages either didn’t work or backfired (thankfully, the optimistic message we created—based on The Power of Us—was the 3rd most effective, from over 252 submissions).

It also suggests that there are very serious downsides to doomerism. It might be fun to get engagement on social media, but the reward system there does not apply very well to the things that drive real policy change or behavior. We should be very wary about leaning on doomerism when the same set of facts can be conveyed in a more powerful message.

This has been well known for some time in the persuasion literature. Messages that appeal to our fears (known as fear appeals) are only really effective when they increase a sense of efficacy and focus on one-time behaviors. Alas, the doom and gloom messages on climate change often undercut a sense of efficacy and require repeated, long term habit change.

Does this mean we should avoid sharing the scientific facts about climate change? No, not at all. In fact, the message about scientific consensus was more effective than negative emotions on every single measure in our study—except sharing on social media. In short, people are highly responsive to scientific messages when they are framed in the right way.

We asked Jamie Hyneman, one of the most prominent science communicators in the media and former co-host of MythBusters for his thoughts on effective climate change messaging. He suggested messaging that provides 1) clarity of action and 2) appeals to morality and ethics.

“Looking at the ethics might be the way to go, more specifically, what is the right or wrong thing to do and what does that look like? The morality aspect of climate change is one thing that stands on its own and transcends identities – like whether you’re conservative or liberal.”

His intuitions were on point: our study confirmed that messages with moral foundations yielded the most motivation for positive climate action. And we have found that framing messages through a moral or ethical lens can make people feel more strongly about almost any action—from riding a bike to studying for a test. This might be a lesson that people should take to heart.