Money is the drug that sustains our delusions, covers our denial and, unless checked, foretells our demise. The ecological anxiety at the heart of that denial is like a phantom limb, a nagging pain continuously reminding us that the loss is ongoing and that the blessings of our natural wealth are disappearing. Money drives it all. Wealth is deferred grief.—-Martin Prechtel

The most common relationship between money and grief is well-known. Within a family system, the loss of financial stability and the challenges of unwinding financial relationships coming in the wake of a death are inescapable. There is also a documented relationship between the loss of a loved one and excessive spending that becomes a form of self-care. There is a world of coping mechanisms to find our way through the crushing experience that comes with such losses.

There is another form of grief which is getting increasing attention, and which has become a recognized psychological health issue for society at large and especially among indigenous groups, displaced and marginalized communities, younger generations and especially among those directly impacted by climate change: ecological grief, or what is also called solastalgia. The collective experience of this form of grief may not be universal, but as the direct effects of climate disruption become more intense, more widespread, and more frequent, human distress syndromes are increasing as well. It’s a response to the loss of biodiversity, species extinction, global pollution, and the general erosion of planetary life support systems as well as to the more direct impacts that come from local change. We see the future eroding before our eyes. It’s as visceral a feeling as any other, even deeper, existential. It’s a nagging anxiety, a feeling of helplessness and a sense that something beyond our commonplace comprehension is so very wrong, that we are losing something which can never be replaced.

The sources of that feeling are many. It could be withering crops, declining fish supplies, the local transformation of weather and water cycles, a flood or unprecedented heat. More generally, we can point to deforestation: 10,000 acres per day in the Amazon including in Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, Venezuela and Brazil. Other major areas of deforestation include the Mekong basin, Indonesia, Borneo and New Guinea, Central & Sub-Saharan Africa. We can also point to a lengthening list of major cities rapidly sinking due to subsidence and anthropogenic climate change: Bangkok, Dhaka, Amsterdam, Ho Chi Minh City, Houston, Miami, New Orleans, and Venice, to name a few, together totaling fifty million people.

Since we’re at it, let’s not forget Jakarta, another eleven million. The Indonesian government plans to re-locate the capital of Indonesia, one of the most congested, polluted and earthquake-prone cities in the world, eight hundred miles away to Borneo, where rainforest will be leveled, hundreds of species will be destroyed, and an entire planned city will be erected. Our guts tell us this is wrong, to compound the damage already visited upon Jakarta by destroying more rainforest, further diminishing biodiversity, and displacing indigenous populations.

We can point to rising temperatures causing accelerated melting of the glacial coverage throughout the Hindu-Kush Himalaya, which exacerbates a positive feedback loop.

Approximately 2 billion people rely on the rivers that flow from these mountain ranges. As well as providing a water supply for humans, livestock and wildlife in the region, freshwater originating in the cryosphere is essential for agriculture, hydropower, inland navigation, spiritual and cultural uses.—-Martin Prechtel

China is building coal-fired power plants to replace the huge losses of hydropower due to inadequate supply in the Yellow and Yangtse River basins (fed by Himalayan runoff). We can point to groundwater levels dropping everywhere, or deepening drought across the 25% of humanity occupying South and Central Asia, Southeast Asia as well as central and northern China.

Martin Prechtel, in his book, The Smell of Rain on Dust, writes about money and grief in a startling and clarifying way. For him, money is the measure of our collective grief for the losses it represents. Money is loss, not gain. Money is also the measure of our dissociation from those losses. Its appeal may be universal, yet it doesn’t remove the feeling of loss that quietly takes up more and more space in our consciousness, to which we respond like a textbook version of addiction: more. Money is the drug that sustains our delusions, covers our denial and, unless checked, foretells our demise. The ecological anxiety at the heart of that denial is like a phantom limb, a nagging pain continuously reminding us that the loss is ongoing and that the blessings of our natural wealth are disappearing. Money drives it all.

It may seem an extreme or even absolutist view to say this story of rising and spreading grief must be told, that we must awaken from the ‘numbing trance of having channeled our ungrieved sorrows’ into ever more destructive choreographies of torturing the Mother (and ourselves). Since the second Industrial Revolution, what we are witnessing is the way money saves us from having to metabolize that grief while causing untold damage for profit—and then doubling down on immeasurable future damage for the sake of even greater profit.

Business is using the weight of the wreckage of the past, of unmetabolized sorrow as an exchange for goods and services in the present, and investment for gain to escape the debts of the past in the present and to blast into the future. —-Martin Prechtel

Looking at money this way, we can quantify and even visualize our grief for a world that is disappearing.

A direct relationship between the parts per million of carbon dioxide and the plutocratic pronouncements about how we humans are going to change our profligate ways is clear. At the same time, we avoid even the suggestion that the growth of money and debt driving that measurement might in any way be disguising the reality of our losses. To fully experience that ocean of grief would require the termination of the operating principle of growth: debt.

Mostly, we are captured, mesmerized by the convenience of money, the ubiquity of it, perhaps never quite connecting its presence as a substitute for a visceral sense of absence, the disappearance of the true wealth it represents. ‘Wealth is grief deferred.’ (Prechtel) Instead of realizing what we are losing by the ongoing game of debt-driven non-renewable resource extraction, the seductions of money blind us to the advancing environmental losses as well as to other ways money substitutes for interpersonal relationships, community and belonging.

The measure of that grief is depicted as the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which today, as I write, is 423 ppm. It’s quite an appropriate measure as carbon dioxide emissions record our lack of restraint as we burn the future right here in the present. The crisis is a consequence of our combined dependence on non-renewable energy sources with the accumulation of massive global debt to fuel economic growth, continuing in the absence of a coordinated global response to mitigate the consequences already upon us.

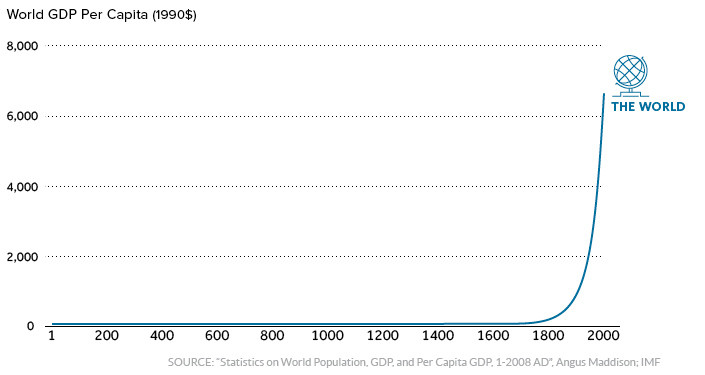

There is no argument that the discovery and deployment of fossil fuels has generated a more dramatic change in GDP and economic benefit per capita since the beginning of the common era than at any other time in human history. The correlation between energy consumption and the growth of GDP (Global Demolition Potential?) is clear and compelling. We also sense, without even looking at the data, that the extractive economic system, of which climate change is only one manifestation, is heading toward its apotheosis.

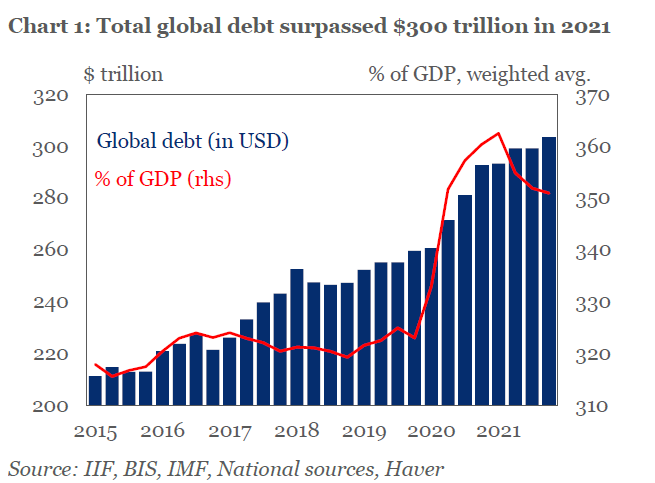

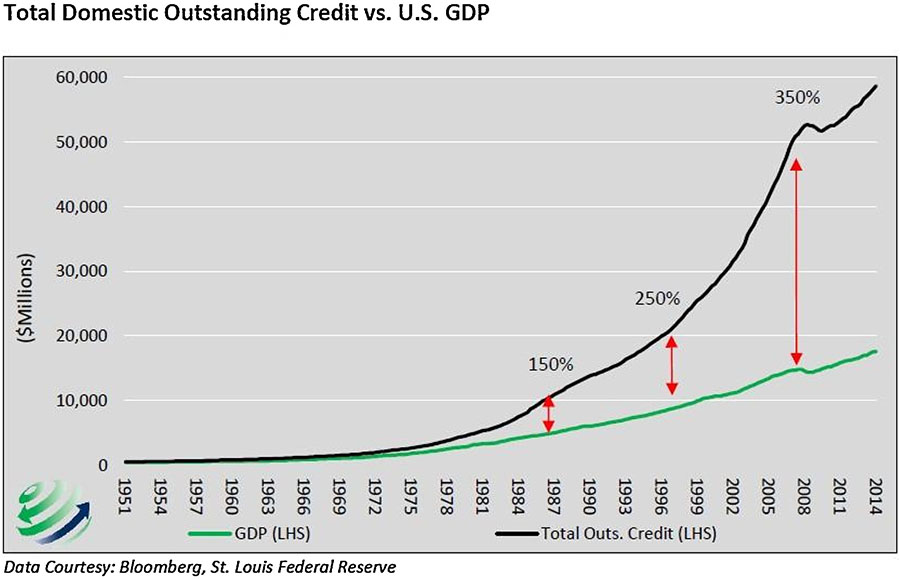

The imperative of the current economic model is growth, fueled by the creation of money that did not previously exist. Every issuance of debt is a promise to the future that the wealth already strip-mined, the progressive amputation of limbs from the global body turned into money, will continue. And yet the global debt-to-growth ratio has been degrading for some time. More and more debt does not produce the growth it once did. Since 1980, the gap between debt and growth has grown, now reaching a ratio of global debt ($303 trillion) to GDP of 350%.

Renewables may now represent the great majority of new energy sources, which might seem like the way to balance accounts with grief, but fossil fuels overall will continue to be the predominant source for many years to come. A belief that renewables are now replacing fossil fuel use on anything even remotely close to a 1:1 basis is a myth not only because demand for legacy energy continues to grow, but renewables must also account for their own emissions in the manufacturing process. Even though the growth of renewable energy sources is impressive, it is not now on a path to overtake our reliance upon non-renewable sources by 2050. The mitigation of our existential grief is not happening fast enough to make a difference any time soon.

The current per-capita debt of the Unites States alone is now almost $120,000. In the era of Modern Monetary Theory, in which money is created out of thin air, this figure may have little meaning. The global debt to GDP ratio (depicted above) may rise to 400% or even 500%. But it cannot rise to 600% or 700% without radical readjustment because the cost-benefit of that debt will continue to fall due to the complexities and limitations of the resource base. More money cannot create more resources, whether it’s fossil fuels or copper, lithium, or even concrete.

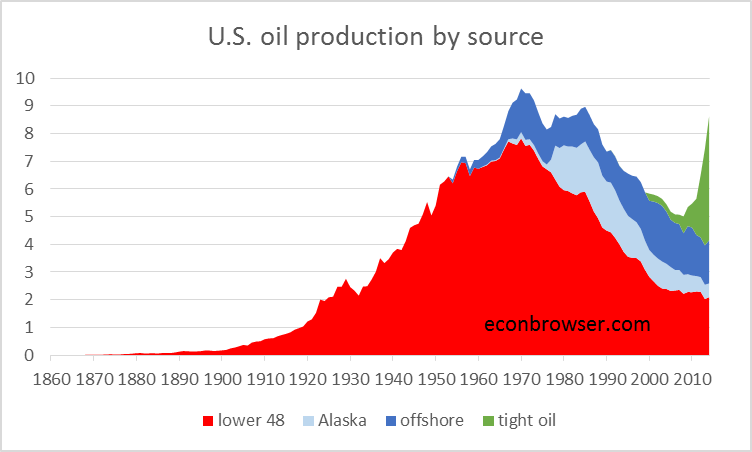

The United States reached peak oil production in 1970, validating Hubbert’s 1956 prediction. Despite being the world’s largest producer now, the US has never recovered its capacity since that year. As the figure above indicates, nearly 90% of all the increased production in the US since 2005 has been from fracking and is the only reason total US production approaches the 1970 peak. Of the eight main fracking fields, seven will likely peak by 2025. Beyond that point, the US capacity to respond to any other interruptions of supply (geopolitics) using domestic production will become increasingly difficult. Considering normal increases in domestic, not to mention global demand, and in the absence of new supply coming online in the near term, prices for gasoline and all other petroleum products will march upwards—at least until renewables, not anytime soon, do catch up and replace oil on closer to a 1:1 basis.

Using debt to compensate for the increased cost of extracting non-renewables is an avoidance tactic. It pulls consumption forward, creating an illusion of abundance to the average consumer and to the average elected official. More of the resource is consumed more rapidly than if financing was reduced (or became impossible). Policy follows that illusion by facilitating more extraction, which generates the ever-increasing gap between debt and production, depleting the resource supply more rapidly and driving the desire for even more debt to further pull consumption forward and sustain the illusion of cheap energy and/or abundant mineral resources. This is how our grief gets kicked down the road.

Economies will only grow if they can borrow money. But we’ve been consuming beyond our means for more than 50 years. The cost of energy (and the cost of financing) is rising because the energy derived from production compared to the cost of production (the energy return on investment, EROI) is on a long and slow descent into single digits. Demand continues to push discovery and drilling enough to increase pricing while EROI continues to trend downward. As the costs of exploration rise while EROI falls, rising risk will raise the cost of money. In a sense, measures to hide our grief from ourselves will become ever more extreme.

As the mad rush to renewables continues, especially in Europe, China, Canada, Japan, North Africa, and the Middle East, sinking more capital into conventional oil, oil sands and tight oil development may extend global supply on a teetering plateau for a few more years, maybe even all the way to 2040. However, Dellonoy et al (2021), modeled an all-oil peak in the next 5-10 years. The most significant finding was that by 2050, half of all gross energy production will be ‘engulfed’ by the costs of production. That is an EROI of 1! When it takes one barrel of oil to produce a new barrel of oil, it’s game over. That will be the moment when growth, debt and grief will achieve singularity. That will be the moment when the value of money will erode, and we will face an imperative to finally metabolize the grief that was so long stored in that value.

The [earth], in hopes of being heard, tries to adjust her temperature and temperament to help fill all the holes, wounds and insults to her over-generous self, rents and tears caused by a non-praising mentality of some desperate humans who keep opting for more power and the increased temporary cleverness of technology, to escape nature’s inevitable confrontation. A confrontation made necessary by our uncaring-earth-ravaging actions, thoughts and pared-down language of people who will not even kneel in front of what gives them life.—-Martin Prechtel

©Gary Horvitz, 2024.