Listen to anyone committed to addressing climate change today and what you’ll hear is talk of “carbon markets” and “green capitalism”. According to this thinking, the climate problem can be solved primarily by nudging public and private investment towards climate friendly technologies. Climate change in other words, stems from market imperfections that can be solved through reengineered investment structures. No disruption to the fundamentals of our economic models is necessary; no sacrifices required. The orthodoxy of neoliberalism remains secure if only mildly altered.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote of the hazards of doing things on the cheap, of trying to get something for nothing. While he wrote theologically, his concept of “cheap grace”, the act of seeking salvation without contrition, forgiveness without repentance, is instructive to this attempt to solve a complex problem through easy means.

In the Bonhoeffer vernacular, today’s obsession with green markets amounts to Cheap Climate Grace, seeking climate salvation, without questioning our socio-economic behavior, or committing to structural change, i.e., “costly grace”. We can happily have our infinitely growing cake and eat it too; only now it’ll be greener. What is so tragic about this eco-market gospel is that it not only completely misses the point, but that it peddles a failed remedy for a misdiagnosed problem in the process. Years of failed experimentation with carbon pricing have stemmed neither the overall growth of greenhouse gas emissions nor the eco-marketers’ enthusiasm for its presumed utility. Cheap Climate Grace fails to understand that climate change, economic inequality, and social injustice all stem from an economic system exclusively focused on wealth accumulation while using the planet as its dumpster. Worse, Cheap Climate Grace signifies collective moral corruption in its superficial attempt to address a grave wrong while maintaining the status quo of the system and lifestyles that gave rise to that wrong.

Cheap Climate Grace results from misinterpreting the climate change challenge. From the time climate change emerged on the political scene, we’ve pursued alternating definitions in our response to it. We initially – and to a degree still – defined it as an environmental problem. With little to show for those efforts, we turned climate into an economic problem which could be fixed through market reforms, profitably ushering in a cornucopia of climate mitigation technological fixes ranging from solar panels and wind turbines to heat pumps and EVs, while leaving the fundamentals of the economic system intact. Climate salvation on the cheap.

Eco-marketers, using such sanctifying terms as “sustainable growth” and “green finance”, maintain that the fault lies not in capitalism and its drive for infinite, ecologically rapacious and socially unjust growth, but in poorly designed markets. Tweak the markets and magically, consumption, like profits, can continue to grow unabated. They insist this economic model, premised on ceaseless consumption, once updated, can reduce greenhouse gas emissions while accelerating economic growth. But no amount of financial alchemy can resolve that contradiction.

Market fixation and its ideological sister, technological fetishism, are distractions at best and delusional forays at worst, forsaking transformational imagination for ideological inertia. They repeat our penchant for seeking the easy way out – the cheap way out – of our problems. They reveal a bias for the conventional and a fierce reluctance to disrupt either individual or institutional habits.

We prefer defining climate change as an economic problem because by doing so we avoid asking anything from ourselves or one another. Market solutions and technological fixes don’t ask for introspection, let alone repentance. Better to reform our markets than ourselves. But illusory fixes won’t get us out of this mess. Climate change requires something akin to Schumpeter’s “gales of creative destruction” of our entire political economy. Simply swapping out brown electrons for green electrons may give us a cleaner energy economy, it is doubtful it will give us a more equitable and just society, just new wine in old wineskins.

Climate change is a clarion call for a reevaluation of who we are. It is an invitation to reassess our relationships to one another, to our community, and to our environment. It’s an opportunity to revisit our political and economic assumptions and to design a new system that is more just and equitable. Substituting tired economic mentalities for essential existential questions is literally killing us. The climate change question is far too big to be answered with the smallness of market manipulations. We may not know what a new system looks like, but we will never know if we cling to yesterday’s thinking, pushing misdirected and failed remedies, cloaked in language intended to assuage the ecologically concerned.

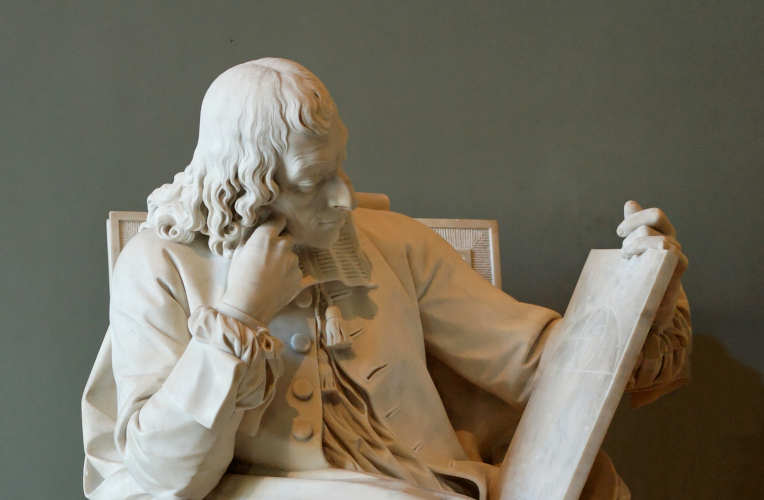

Pascal famously said that the “sole source of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to sit alone in a room.” It’s time to grab some solitude, think fresh thoughts and rekindle forgotten dreams. We’ve tried tackling climate change through models that prop up the economically and morally crippled structures of the past, let’s try an approach that looks to the future with courage, vision, and imagination. For unlike Bonhoeffer’s God who does in fact offer grace freely, the climate god does not, and thus in our eagerness to seek cheap rather than costly climate grace, we may very well end up receiving no grace at all.