This is the third in a series (ed.note, previous posts here and here) addressing the global energy transition imperative as an accelerating threat to human rights and as an opportunity to interrupt continuing injustices, to examine and revise a global ethic of development in favor of human and earth-centric values.

Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is a provision of the United Nations Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) intended to support substantive deliberations between States, companies, and indigenous tribes. It calls for consultation with tribes in consideration of their autonomous economic, social, and cultural development. Three of the largest per capita emitting nations (Australia, Canada and the USA), with considerable mining reserves lying on First People’s land, voted against ceding consent to them for future mining operations. In fact, most nations, while supporting the measure, do not in practice, by any measure, accord veto power to tribal communities regarding the disposition of natural resources on their territories. An important legal catch in many cases is whether lands are acknowledged by governments to be indigenous homelands at all or whether they were even colonized. If not, for what reason would a government have an obligation to provide free and informed prior consent?

A few relevant articles of the UNDRIP include:

- Article 11: Indigenous peoples have the right to practice and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present, and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, and technologies.

- Article 26: Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories, and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired.

- Article 32: Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources.

- States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water, or other resources.

The principle of FPIC in the UNDRIP does not determine whose interests shall be paramount in any dispute or contractual negotiations over indigenous land or resources. Few nations have formally adopted the measure. In practice, the references to consultation and consent are sufficiently muddied for states to exercise sovereignty (or eminent domain) over indigenous land while providing just enough leeway for indigenous groups to assert their right to vigorously oppose a proposal. Hence, disputes are decided in court.

The skeptics of FPIC often point to the UN Declaration as being a “soft law” document, meaning that it is aspirational but not legally binding. “…at the end of the day, companies get their licenses from the states, and then are empowered by the state to either ignore Indigenous people or engage with them. Source

The consequence of the lack of clarity of the FPIC is that when it comes to potential development projects, companies and states may point fingers at each other as the culprits. But the ultimate power to declare eminent domain is deliberately affirmed. Each situation is resolved according to whatever opposition has been mustered and whatever degree of engagement the state chooses as well as the anticipated value of the proposed project. Thus, in concept and practice, the original votes in the UN for FPIC were toothless. It is not a guaranteed shield against erosion of the indigenous economic base, destruction of their socio-political institutions and desecration of their spiritual bond with the land. In fact, in the Philippines and elsewhere, FPIC has been used as a bludgeon to coerce tribal compliance with the designs of the State.

The principle of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) enshrined in the [Filipino] Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) provides a shield against the oppression of indigenous peoples. However, in myriad cases, this protection is theoretical as these peoples’ consent has been misrepresented, extracted through deceit or machinations by a government in collusion with business, or obtained under an ambiance of trepidation including human rights violations. Source

Following this brief review of how the Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is interpreted by nations, companies and finance institutions, a look at two nations (the Philippines and Ecuador), will illustrate the practical effects of these interpretations. In the Philippines, the Regalian Doctrine, a version of the Doctrine of Discovery (1493) justifying the domination and oppression of indigenous populations, was a declaration by colonial Spain that all lands belonged to the King. Even though the Philippines achieved independence from Spain in 1898 and from the United States in 1946, the Regalian Doctrine, or what could also rightly be called Manifest Destiny, retains legal standing in territorial disputes between indigenous minorities and the State. In this case, the King has long been replaced by the State.

In the century following independence from Spain, vast tracts of indigenous territories were appropriated by the State. The Philippines became a glaring example of land expropriation, marginalizing indigenous peoples, turning them into squatters on their own ancestral lands, denying them any influence on the allocation of mining, logging and hydropower contracts, and impoverishing them in the process. Indigenous peoples received no compensation and were often forcibly removed from homelands. The presidency of Ferdinand Marcos (1965-1986) was particularly damaging to indigenous peoples. Even though the nation passed its own version of a declaration of indigenous rights (IPRA in 1997), it left intact all prior concessions, sales and land grabs. Land disputes continue to weigh against minority rights in the courts which ultimately reject every possible rationale for codifying authentic indigenous sovereignty.

Even after persistent international focus and the passage of the UN Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP 2007), the Philippines has managed to manipulate land disputes in favor of the state by casting indigenous leaders as terrorists, fomenting internal divisions within tribes, military occupation of indigenous lands, restriction of movement, interruptions of tribal commerce, and creating sham deliberative bodies to influence negotiations with the State. Indigenous efforts to oppose further appropriation of lands for private purposes without compensation are also stymied by a completely captured bureaucracy and compromised courts.

Ecuador is another revealing example of how the influence of foreign mining interests can be a socially and politically divisive force. Having attempted to reduce dependency on oil and gas extraction, Ecuador was forced to face the unfortunate dilemma of replacing the revenue of those operations. Amid the complexities of sustaining social programs and finding a pathway to a new energy economy, the government was compelled to turn to mining and hydropower. Ecuador has a rich belt of copper reserves which up until 2009 had been mined by Canadian companies until their assets were purchased by a Chinese conglomerate in 2010. Ecuador also has gold, silver, zinc, uranium, lead, and sulfur.

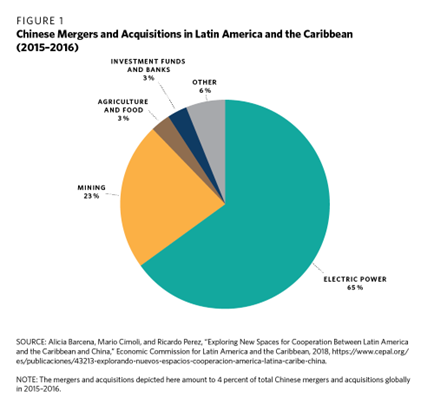

The Chinese interest in the Ecuadoran mining sector was intended to interrupt the combined monopoly power of BHP, Rio Tinto, Vale, and other mining conglomerates, and to secure the supply for growing Chinese domestic industries while also elevating Chinese influence in the global market. Mission accomplished! As depicted above, Chinese financing throughout Latin America includes $137B in loans since 2005 and has greatly enhanced their financial power in other economic sectors.

A 2008 Ecuadoran General Mining Regulation excluded the FPIC provision, meaning that mining interests were not compelled to follow internationally accepted regulations regarding consultation with or consent from indigenous interests. This provision, plus Ecuador’s Public and State Security Law (2009) “gave the country’s armed forces a mandate to protect the facilities and infrastructure of public and private companies from the fallout of opposition to their commercial activities” along with a “general softening of social and environmental safeguards” by the national government. Chinese entry into the market was smoothed.

Gold mining is a high-value crop. The indigenous response to copper mining is quite different. Whereas the government takes a relaxed posture toward multinationals undertaking huge metals projects, failing to enforce regulatory frameworks, it has taken a more aggressive posture toward illegal gold mining. Popular opposition to Chinese gold mining has also had some success. But economic imperatives in indigenous territories have also spurred small-scale illegal mining, heavily polluting waterways and impacting biodiversity due to widespread toxic release of mercury.

The influence of the government, financial elites, and large landowners in facilitating the entry of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises (and others) cannot be overstated. In more remote territories with an absence of government oversight, multinational miners have taken advantage of local populations by co-opting local leaders, pitting indigenous communities against imported landed interests, acquiring land by questionable means, manufacturing consent, threatening eviction, and ignoring government regulations.

Although the government has at times positioned itself as an advocate of indigenous claims and rights, the need for foreign investment has largely trumped such efforts, resulting in bending to the will of foreign commercial miners. Chinese companies have since taken advantage of these conditions by negotiating directly with political elites in Quito, largely ignoring local community interests entirely.

Working through two subsidiaries, the Chinese mining consortium has responded to localized criticism with a blend of tactics that includes co-opting select local figures, colluding with national officials to sidestep environmental and socio-cultural safeguards, and coercing inhabitants into relocating under the threat of force. By turning Ecuadorian national elites against locals and using divide-and-conquer tactics among Indigenous communities, the Chinese-led mining projects have entrenched existing political cleavages, undermined community cohesion, and ultimately harmed Ecuador’s democratic fabric.

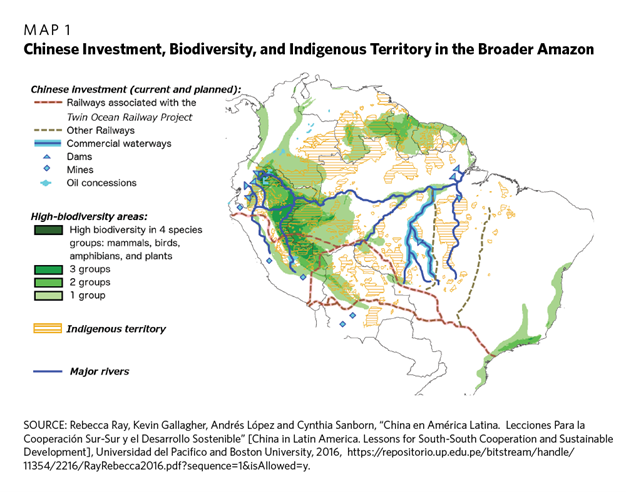

The figure below illustrates the nature of Chinese investments, their overlap with indigenous territories and their impact on biodiversity.

Operating in what has become a culture of virtual impunity, the collusion between Chinese companies, Ecuadoran security forces and government officials has become increasingly violent, even earning a rebuke from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Ecuador. There has been some recent pushback by Ecuadoran courts on the principle of FPIC. But the influence of Chinese companies has fragmented Ecuadoran unity, pitting the government against tribal communities, threatening their livelihoods and ancestral homes, all of which replicate the tactics used within China to enforce domestic compliance with government policy. We can assume these State-Owned Enterprises are operating with the explicit approval of the Chinese Communist Party.

For the government, the allure of alleviating the ballooning sovereign debt (which has risen from $16B in 2012 to $66B in 2022) is too great. Though it defaulted on some of its sovereign bonds in 2022, Ecuador has managed to become one of the more attractive investments in the world. Mining must have something to do with that. This entire scenario has been driven by domestic elites willing to bear any cost to follow the neoliberal agenda.

There is now a rising international push to force companies to acknowledge human rights and indigenous rights even if nations do not. Companies cannot hide behind soft laws or muddied ethical standards like the UNDRIP or FPIC. But make no mistake, Ecuador has fully joined the mineral extraction economy. Although resistance to large-scale mining has not been entirely futile, the contradictions between pronouncements and practice could not be more obvious. It’s almost as though they learned from the Philippines. What Quito may have overlooked is the likelihood that increasingly coercive tactics have a way of galvanizing resistance not only among indigenous communities but also among the general population. This is the stuff that flirts with armed rebellion.

Citations:

FPIC: A Shield or Threat to Indigenous Peoples’ Rights?

Indigenous Peoples Rights Act

Gold rush in Ecuador’s Amazon region threatens 1,500 communities

Ecuador deploys soldiers against illegal mines in Amazonian areas

Ecuador mining industry to grow eightfold by 2021 — report

Chinese Mining and Indigenous Resistance in Ecuador

Regulation to the Mining Law in Ecuador

The Law on Police Use of Force

INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS* CASE OF FLOR FREIRE V. ECUADOR JUDGMENT OF AUGUST 31, 2016

The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Chinese investment in Latin America plagues people and nature: Report

How Locals Halted a Chinese-Owned Gold Mine in Ecuador

The oil trap – Ecuador’s quest to clean up its energy mix