I try not to get dragged into local British politics here: there’s no point in dwelling on private grief. But sometimes local British politics throws up moments that resonate more widely.

We had one of those moments in the recent set of three Parliamentary by-elections held on the same day. In our first past the post system, the Conservative government lost two of the seats on swings against the government of twenty per cent plus. Against expectations, it held one seat, Uxbridge, on the edge of London, where the swing against the government was only around seven per cent.

The reason for this exception was quickly identified as being the Mayor of London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) policy, about to be extended to the outer London boroughs, including Uxbridge. The ULEZ policy basically charges people who have high-polluting vehicles for driving their cars inside the ULEZ zone. The Conservative candidate had run what amounted to a single-issue campaign against ULEZ.

Air pollution

London, generally, has high levels of air pollution compared to other European cities. The Mayor, Sadiq Khan, has made addressing this one of his flagship policies. And introducing the ULEZ was a requirement imposed on Transport for London as part of a government funding agreement, although not necessarily as far as the outer London boroughs.

One of the consequences of this by-election result, therefore, was speculation that the Conservative government might run against climate change measures in the next British next general election (which will probably happen in 2024) and some back-tracking noise by the Labour opposition on climate policies. I’ll come back to this lower down, because it raises some wider issues.

Car use

But the issue also reveals something of how transport plays out at the political level. Because: policies that restrict car use are almost always progressive. They reduce the external costs of widespread car use, whose benefits tend to go to the more affluent and whose costs tend to go to the less affluent.

But also: such policies are also a lightning rod for a certain type of politics on which it is easy to mobilise particular groups of voters. (We’ve seen something similar with Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, despite the evidence on traffic displacement and on air pollution.)

On Twitter, Luke Tryl drew on social research to underline that this is because those groups of voters—and others—link the car with “driving and freedom”:

I’ve been struck by how often when asked about driving, people in focus groups will use the word “freedom” to describe what they most like about it – the ability to go where they want and when they want and not be reliant on anyone else. The offer of better public transport doesn’t appeal against this frame, because that makes you dependent on others and the whims of services timetables/available routes, you’re not free to go as you choose.

‘Freedom’ and ‘self-reliance’

This is particularly true of particular groups of voters, especially those who emphasise “self-reliance’, which Tryl’s organisation, Our Commons Ground, found to be over-represented in the Uxbridge electorate.

It’s possible to go way wider than this, of course. The car—as an artefact—is the basis of twentieth century consumer capitalism, at both an emotional and practical level, and it has been embedded in our societies through vast public expenditure on infrastructure. At an emotional level, it atomises society.

As well as notions of “freedom” and “self-reliance”, it also amplifies notions of individuality at the expense of shared public good. The economics of car ownership also matter: it is an expensive item that tends to lock people into long-term credit agreements. (Ivan Illich used to include the time spent working to pay for the car in his calculation of their overall average speed.)

Dealing with climate change will take state intervention, and so you can see how right-wing parties might think that playing the “freedom” card could be a good move, putting the ethical and practical issues about climate change impacts to one side here for the moment.

Culture wars

In The Conversation, Ed Atkins suggested that we are already here:

My research shows net-zero policies are the next target of right-wing populism and culture wars in the UK. Narratives are emerging that tie complaints about climate policies being undemocratic or expensive to issues of Brexit, energy security and a “green elite”.

Again on Twitter, the political commentator Ian Dunt noted —in his typically ‘robust’ language — the way in which climate change policies were being rolled into “culture war” politics by right wing parties internationally. As he says, the specifics of the Uxbridge by-election result will have no bearing on the general election. (There are also specific reasons for this particular by-election result in terms of timing: policies that restrict car use tend to be at their most unpopular just before they are implemented, as was the case in Uxbridge.) The issue is wider:

However, in the long term, it’s very disturbing. It demonstrates the kind of opposition which can be rallied to environmental policies and how easily the Conservatives could be seduced into leading it. We’ve seen this in Europe. The gilet jaunes movement was a response to cutting speed limits and raised fuel taxes in France. There was outrage in the Netherlands over reduced speed limits to comply with emissions targets.

Right-wing populists

In different parts of Europe, right wing populists have tried to make something of this anger. Dunt mentions the Dutch Party for Freedom, the Sweden Democrats, and Alternative for Germany. So it’s easy to imagine the British Conservatives, currently a hard right party in a terrible electoral position, following suit:

The Tories will be desperate after the next election. It’s very easy to imagine them being seduced into becoming cheerleaders for those angry about climate change policies.

And desperate even before the next election. And what’s this? As I googled ‘low traffic neighbourhoods’ on Sunday morning to check the sources of the research about it, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is all over the ‘news’ feed:

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has ordered a review of low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs), saying that he is on the side of drivers.

Political strategy

Reading a bit more about this ‘review’ of ‘anti-motorist policies’, it is classic performative politics, which probably underlines the culture wars point. To prevent councils from imposing 20mph speed limits would require new primary legislation which the government hasn’t got time to draft or get passed. The Department for Transport doesn’t even have a definition of what is, or isn’t, an LTN.

But it wasn’t a one off. There clearly is a political strategy here. Sunak followed up, the very next day, by approving 100 new oil and gas drilling licences, throwing in a trip to north-east Scotland to make a speech about it. The Financial Times noticed that, more quietly, the government had reduced the carbon price in Britain compared to the EU and the US.

Popular Net Zero

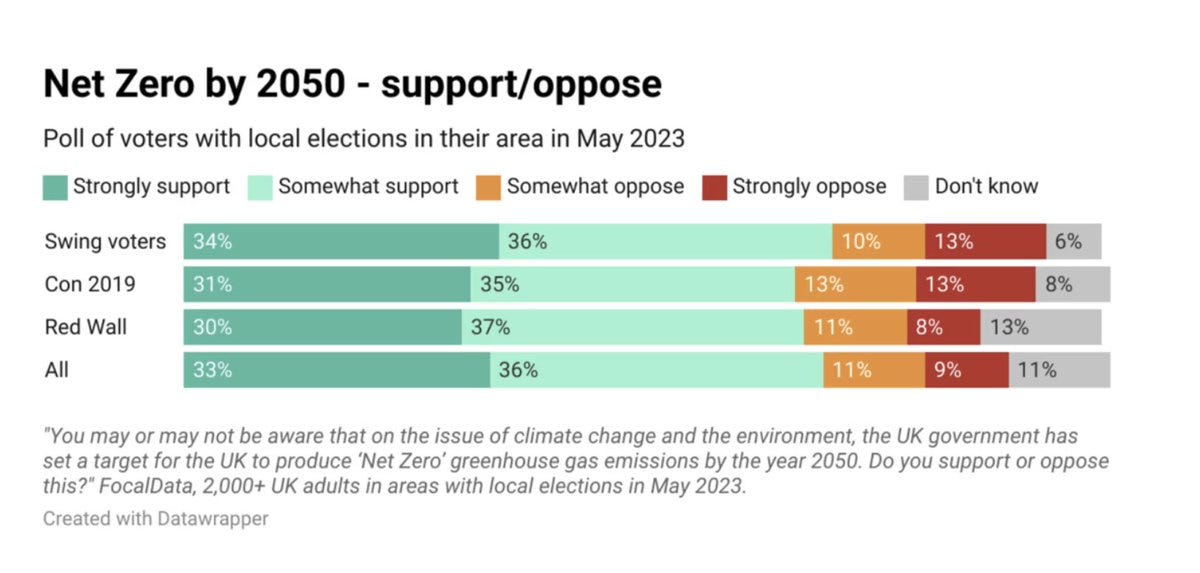

Of course, it may not be great politics to do all or any of this. Polling shows that people like LTNs. In the UK, climate change typically comes out as a top three or top four issue of concern when you poll voters. As Robert Colville of the small-c conservative Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) pointed out, policies to get to Net Zero are uniformly popular across the electorate:

(Note for non-British readers: the so-called ‘red wall’ in this refers to former Labour-held seats in pro-Brexit areas in the north of England that voted in Conservative MPs in the 2019 election. These voters are generally believed to be more conservative on social issues.)

…and popular policies

When asked about specific policies, most ‘net zero’ policies mostly have support on a scale that runs from solid to overwhelming:

ULEZ is in negative territory here, along with the British government’s plan to issue new oil and gas drilling licences in the North Sea, although ULEZ polls much better in London than it does nationally. One of the ways this gets framed is that “measures to deal with climate change are popular until you ask people to pay for it.” But as Steve Akehurst points out, the same is true of measures to address crime as well.

While I am doing charts, it is also worth noticing that on climate change measures the British electorate is more progressive than those in France, Germany, or the US. (This chart is by John Burn-Murdoch, the FT’s excellent data journalist.) Progressive opinion is more to the right hand side of each of these lines. Britain is the red line.

Climate action

In the Guardian, Phineas Harper, of the charity Open City, quoted the urbanist George Kafka on why conservative politicians might be so keen to discredit local measures to reduce traffic and related air and noise pollution:

Kafka speculates that the real reason Conservatives may be keen to ignite a car-centred culture war is because the benefits of reduced traffic could boost public support for ambitious green policies elsewhere. “I have a van and I love driving,” Kafka explains, “but low-traffic neighbourhoods prove that life can actually get better with climate action – which is politically dangerous for anyone with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.”

Several of the commentators whose threads I have quoted from above say that progressives need to have a better story about all of this—and in particular need to find ways to reframe the idea of the car as being about ‘freedom’. Robert Colville suggested that eco-change needs to be about “innovation and incentives”, but the CPS would choose to put it into an economic frame.

My world, the world

So let me help here. When I worked for The Henley Centre, two decades ago, our social research publication, ‘Planning for Consumer Change’, had a model that we found helped to encourage progressive change.

(Source: The Henley Centre, ‘Planning for Consumer Change’)

Successful stories about progressive change have to work at all three levels. So, for example, traffic calming measures reduce air and noise pollution, and encourage people to walk or cycle, which are benefits for their physical and mental health. (My world). The local area is nicer to use, so people are more likely to bump into neighbours; crime rates are also likely to fall. (Our world). And at the same time, traffic reduction reduces carbon emissions, which is good for climate change. (My world).

You can tell the same sort of stories about food and other critical social issues. These are not hard stories to tell. And people even like them, because they are about positive change.

—

A version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter (https://justtwothings.substack.com).