Voters are angry. Not just with politics overall, or even parties they would never vote for, but increasingly with anyone who supports the parties and positions that they oppose. Working out the ingredients of this cocktail of anger is fast becoming the holy grail of political mixology. Not just what’s making so many voters in some countries so viscerally upset with their fellow citizens across the political divide – ‘affectively polarised’, to use the jargon – but why it happens more in some countries than others.

Many explanations of affective polarisation have one thing in common – the digitalisation of everything. There are two broad storylines here.

One is about social media: the ways that Twitter, Facebook and the rest reward negative emotional displays, supposedly creating ‘echo chambers’ and ‘filter bubbles’ where those negative emotions about groups with different politics can be reinforced.

The other storyline has to do with economics – more specifically, the labour market.

The economic argument is that digitalisation is increasing economic inequality, in large part by driving what’s called labour market polarisation. This is when job creation happens mostly at the high and low ends of the salary and status scale, hollowing out the sacred middle. Workers who might have been in the middle of the scale find themselves pushed into lower-paying and supposedly lower-status jobs. There, they have to compete with a large pool of workers that often includes recent immigrants.

We are not making a comment about the skills of many low-paid professions here: suffice to say that care work, for example, takes an enormous amount of physical, cognitive and emotional skill.

Technological change is one of the things that drives labour market polarisation, as more and more of the routine cognitive tasks that make up many middle-income roles are either automated or outsourced to cheaper foreign labour markets.

This can lead to stagnant wages and more precarious working conditions. Many lower-paying jobs are also more likely to involve being directly managed by algorithms rather than a human boss – again, the influence of technological change.

With declining real wages, often precarious contracts, and stressful working conditions, parties that use communication tactics or promote policies that prompt strong negative emotional responses are more likely to attract voters then their more temperate rivals. If party representatives and sympathetic media outlets are calling political opponents ‘traitors’ or ‘insurrectionists’, voters are more likely to have a strong or even violent negative emotional response towards them.

This shift often is paired with the creation of a sense of societal schism between an elite who have been the winners in the digitalisation of society and the ‘losers’ who have been forgotten. This is a skill in which Italy’s new populist prime minister, for example, excels.

This type of explanation for angry voters is often deployed on both sides of the Atlantic, viewing the 6 January 2021 Capitol ‘insurrection’ as the culmination of a political polarisation process driven by a rabid media culture, out-of-control social media algorithms that reward extreme emotional responses and a political culture that looks increasingly divergent between metropolitan voters in urban economic hubs and everyone else – bringing together the two digitalisation storylines we mentioned above.

The picture in Europe is decidedly different from the one in the US. Some countries show levels of affective polarisation that equal or even surpass the US, while others remain more tolerant when it comes to relations between citizens with starkly opposing political views.

The reasons for this variation across European countries are still unknown. We think that the answer might lie in taking a deeper look at the history of labour market transformation, de-industrialisation, globalisation and eventually digitalisation.

Until the early 1990s elections in nearly all European countries could be predicted relatively easily, as voters hardly switched among parties, let alone ideological blocs. They tended to vote on the basis of their social and economic class.

For a host of economic and social reasons closely linked to de-industrialisation, this started changing as far back as the 1970s. This is a story of deep social identity transformation, in which citizens increasingly failed to identify consistently with parties.

They now do not divide themselves across traditional groups – socialists, Catholics, liberals, and so on – any more, but rather as unique individuals.

As a result of this gradual transformation, political parties associated with these traditional social identities had difficulty capturing the broad political consent they once enjoyed. By the 1990s this electoral transformation was complete. Unable to count on an ideologically stable electorate, parties started to campaign differently, focusing more on single, current issues.

De-industrialisation, globalisation and digitalisation have further contributed to this dynamic, not least by decreasing the stable political influence of unions. In other words, this is the longer back-story to the two storylines about affective polarisation and digitalisation that we sketched above.

As a result, parties feel a need to increasingly push emotional buttons to attract voters and voters feel increasingly removed from traditional identity bases. A sort of vicious circle is created.

This story about the transformation of politics with the processes of de-industrialiation, globalisation and digitalisation often focuses on the so-called economic losers of the digital race: those who feel they have become poorer, have less security and recognition, and are increasingly pessimistic about the future. But the ‘winners’ in the digital economy are also driving polarisation.

Research suggests that those who have gained economically from technological change tend to support the political status quo even as it fails to seriously address social and economic inequality, exacerbating the dynamics that we think are a cause of so much negative emotion in politics.

What’s wrong with an argument?

But what’s so bad about affective polarisation anyway? A bit of spirited disagreement can be conducive to problem-solving and increase political interest and participation. ‘Issue polarisation’ – taking increasingly divergent positions on political issues – is generally understood to be important in democratic decision-making since it allows clear lines to be drawn on political questions.

High levels of affective polarisation do the opposite, however. Having strong negative emotions about fellow citizens who think differently about politics discourages compromise, encourages escalation of conflict and threatens harm to the basic principles of democratic processes. It also tears at the broader social fabric, affecting our friendships, and romantic and family relationships. Living in such close proximity to enemies of the people can be quite stressful.

Scholars are still unable to explain why in Europe some countries are more polarised than others, and this puzzle won’t have simple answers. Whatever they are, understanding how economic changes driven by digitalisation (and its partner, globalisation) affect political behaviour is becoming increasingly important as some policy-makers look to turn back the tide of negative emotions in politics, while others try to open the dam.

Here is where the details of labour market shifts come back in. Some European labour markets have polarised, others have not. If affective polarisation is partially caused by rising economic and social inequality, one would expect that labour market polarisation, which is a driver of economic inequality, would increase it. To test this idea we would need data about how individuals experience both affective and labour market polarisation. We don’t have that data, however. Knowing that labour polarisation is happening does not tell us the most important things we need to understand: the psychological effects of feeling underpaid, undervalued and overqualified, and how this feeds into political emotions.

It’s looking increasingly like a vicious circle is being created between political parties that benefit from affective polarisation and a sclerotic mainstream political status quo at national and European levels that is exacerbating political polarisation by not seriously addressing questions of labour market polarisation, inequality and social degradation.

This circle is driven in part by labour market shifts that are in turn mediated by cultural and other socio-economic factors. More research is needed, combining empirical study with social and political analysis, to understand how these phenomena are linked and how they can be addressed.

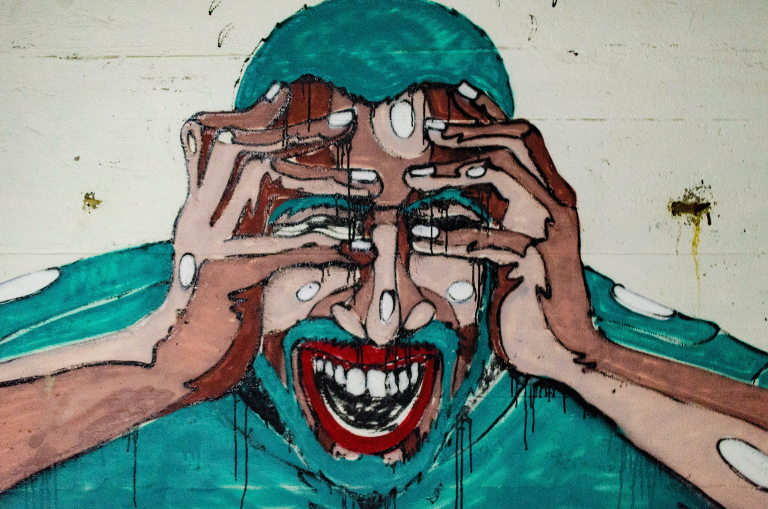

Photo by Aarón Blanco Tejedor on Unsplash