To borrow Hemingway’s famous phrase, political and economic crises happen gradually, then suddenly. And when they do happen suddenly, there are lots of immediate reasons why. The current economic and political crisis in the UK is largely self-inflicted, which raises the question of ‘why?’, but can also be thought of as representing the endgame of a long political wave.

No, you can’t know when the actual moment will be. But over a long period of time, the options keep narrowing until there are no good choices left, at least for the party and politicians that have benefited from that wave. Every political party hits a zugzwang moment.

Forty year cycles

I think it was the politics academic David Runciman who observed that if you looked back over a century of British politics, you could see cycles that ran from economic crisis to economic crisis every forty years or so, with a political settlement coming around a decade later. I can’t find the source for that, though.

This is a heuristic, not a law, and the timings are approximate. But, indicatively, the long depression of the late 19th century ran to 1896 (with Baring’s Bank bailed out in 1890); the 1929 crash led to the depression of the 1930s; the oil crisis happened in 1973-74; and, then of course, there was the 2008 crash.

The political effects of these: the ‘Liberal landslide’ of 1906, the Labour win in 1945 (complicated by the experience of war), Thatcher’s win in 1979 and subsequent victories in 1983 and 1987. And the 2008 crisis is still playing out in our politics today.

Systems patterns

It happens that you see this two-generation pattern in other bits of the literature. Strauss and Howe’s idea of the ‘Fourth Turning’ basically proposes a four-generation model from crisis to crisis. Their four generation pattern more or less goes ‘build’/‘enjoy’/‘exploit’/‘unravel’, although that’s not the language they use. It follows a classic long-run systems pattern, even if some of their post-hoc timings are spuriously exact.

All the same, the mechanism is visible. A crisis leads to a system reset, designed to solve the problems that caused the crisis. For a generation you get a reinforcing loop as the system benefits from this new set of ideas. But all systems decay over time, and a balancing loop kicks in as the problems caused by those new ideas come to the fore.

The advocates of the previous set of reforms retire or die off, and a set of ideas that had some coherence to them either become incoherent, or simply no longer fit the changing political and economic landscape. As David Muir noted, Thatcher said this explicitly of the Labour Party back then:

He added:

Now applies to the Conservative Party.

Conservative decline

So the current British political and economic crisis can be seen as the last twitch of Thatcherism, and by two of its last remaining zealots. I’ll be coming back to the-budget-that-wasn’t-a-budget later in this piece, but there’s another important element here. This is about the long-term decline and de-composition of the Conservative party.

I know this is a strong thing to say. We’re talking about a party that has a majority of 80 seats in the British House of Commons, and one of the givens of modern British politics is that you should never bet against the Conservative party. Over the last century it has been the most successful ruling party in Europe.

But it has been unravelling since the 1980s. In the 1950s, and the era of ‘One Nation’ Conservatism, the Conservative Party was also a social institution, with 2.5 million members across Britain. (In Barnet, in north London, which had 70,000 voters, there were 12,000 Conservative party members. By the 2000s, its membership was less than a tenth of this, and ageing fast. Social values had moved away from the party as well. Economics, which have punished the younger generation, means that the party’s vote is now heavily skewed towards the over-60s and the party’s policies have followed.

Triangulation

David Cameron’s attempted solution to this was to triangulate: a pretence at ‘one nation’ social values to voters (gay marriage and ‘hug a hoodie’), with the party funds coming from an increasingly narrow base within the finance sector, and the core vote shored up with a message that drifted between patriotism and racism.

The first part of that was sheered off by UKIP and the Brexit, while the finance base got narrower (Johnson’s “fuck business” moment in Brussels was emblematic) but Johnson propped it up for a moment with the idea of ‘levelling up’, which appealed to enough voters beyond the traditional Conservative base to win an election. If you’re interested in the political sociology of all of this, the most persistent analyst is the sociologist Phil Burton-Cartledge at his ‘All That Is Solid’ blog—for example in these 2018 pieces—and in his book on the post-war history of the Conservative Party.

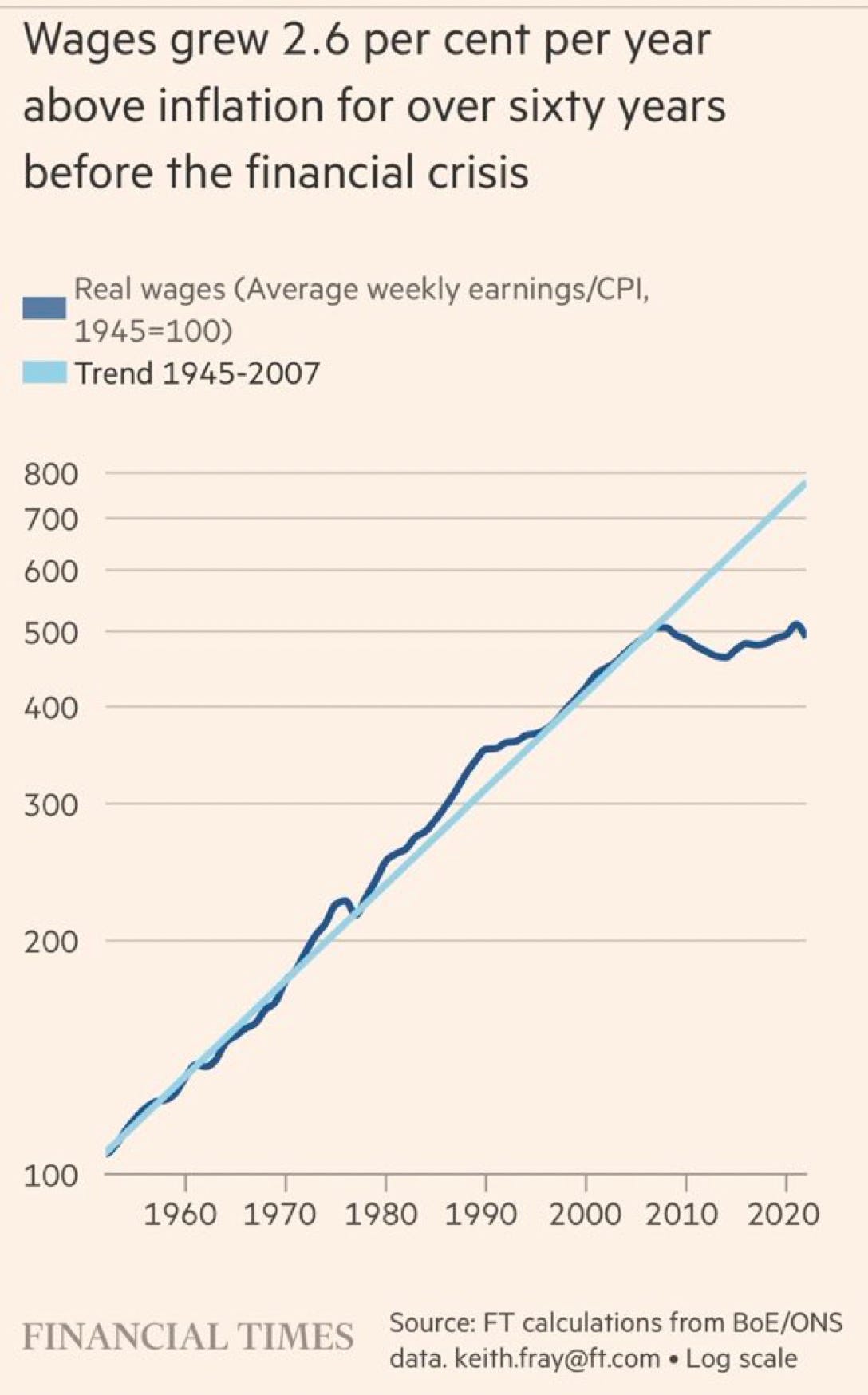

Levelling up was an interesting idea, or would have been had the Conservatives treated it as a strategy and not a slogan. At the least it could have been a programme that dealt with Britain’s real problem, which is captured sharply in a chart from the Financial Times a few weeks ago.

(Britain’s wage and productivity problem. Source: Financial Times)

Flat wage growth

The problem is this: wage growth, and associated productivity, in the UK have been flat since the financial crisis. The causes of this are either complicated, which is the version you get from economists, or they are post-crisis austerity, which killed off the initial post-crisis recovery, followed by Brexit, which had a calamitous effect first on business investment and then on trade.

These together have created the low wage, low investment economy that has characterised Britain recently, with a toxic combination of flat wages and low investment. Paul Mason explained how this worked in practice in a Guardian article a few years ago by using hand-washed car businesses as an example.

And one of the sharper observations on Twitter when inflation started picking up (you can never find a Tweet when you need one) was by James Meadway, who suggested that this low wage, low investment economy also needed low inflation and low interest rates to survive.

Doing something

But for a moment, let’s take the so-called ‘mini-Budget’ at face value. If the rise in inflation and interest rates has wrecked the UK’s low-wage, low-interest rate economy, then the government had to do something.

So, if you want to be generous to the budget-that-wasn’t-a-budget, you can say that it was, as claimed, an attempt to do something about productivity. I’ll pretend for a moment that Truss and Kwarteng were being honest when they said it was a ‘budget’ about growth.

But even this hits an immediate problem. In the 1980s, the idea of trickle-down economics and the Laffer Curve was contested, to say the least, but hadn’t been disproved. Similarly, ‘freeports’ and all of the other mechanisms of supply side economics had not yet been discredited. They represented then part of a suite of theories about how to solve the problems of the previous economic model. But everyone knows that’s no longer true. 40 years on, these are burnt out ideas that don’t work in the way their advocates thought they would.

I have a joke about trickle down economics.

99% of you won’t ever get it.

— David Lammy (@DavidLammy) September 23, 2022

Eric Beinhocker and Nick Hanauer spelt out some of the issues in an article in The Guardian:

As Truss put it last week: “Lower taxes lead to economic growth, there is no doubt in my mind about that.” There may be no doubt in the prime minister’s mind, but there’s a lot of doubt in the data. The US has had four decades experimenting with this kind of economics, and the evidence is clear: not only does it not work but it does enormous damage to the economy and society.

Understanding the government

So what’s going on with our new administration? I think there are four alternatives.

1. They are zealots who don’t realise that the ideas they have believed in for decades are no longer fit for purpose.

2. Or they are working a clever plan to create a crisis to force further cuts in the size of the state and of public spending.

3. Or they realise that they are only going to get one shot at this, and they have decided to help their friends and political supporters cash in before the house comes crashing down around their ears. (Corruption, in other words).

4. Or they aren’t very good at politics.

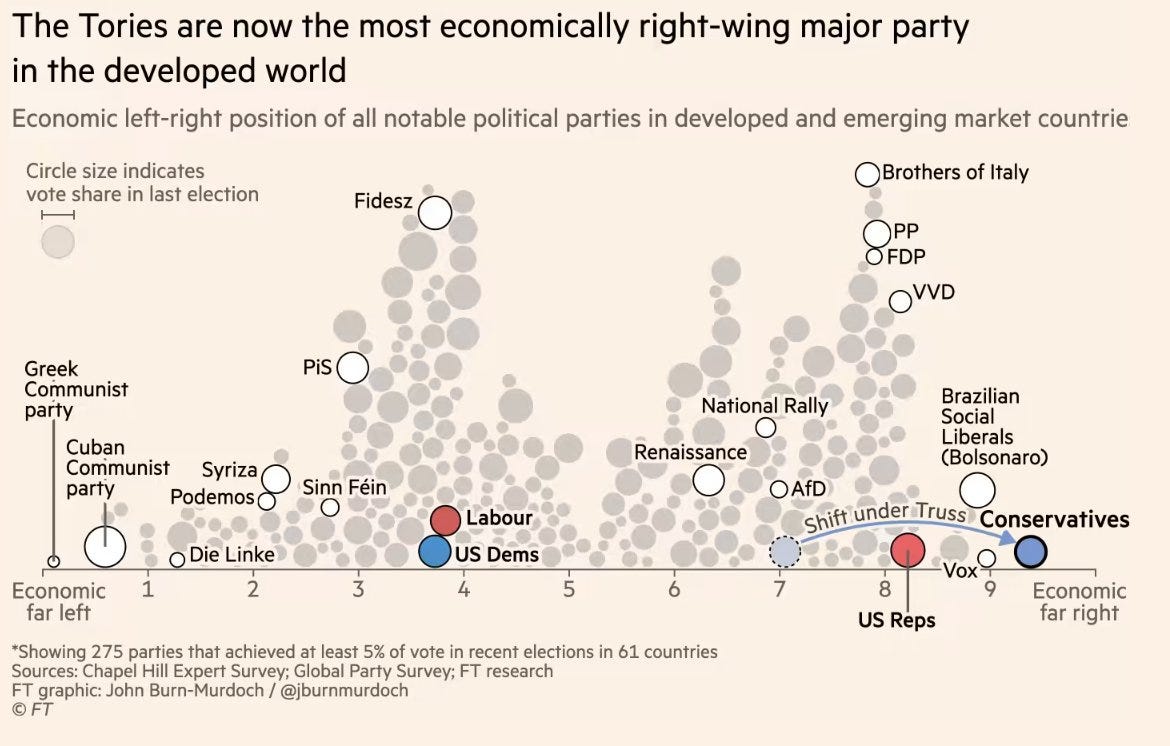

Measuring ‘zealotry’ is hard, even though you know it when you see it, and usually people just point to the libertarian economic manifesto, Britannia Unchained, that Truss, Kwarteng and others co-authored a decade ago. But while I was writing this piece, the Financial Times’ data journalist John Burn-Murdoch published a handy chart mapping economic policies by political party across a number of countries.1 The policies of the current Conservative administration are now right at the edge of the scale, having shifted from the centre-right mainstream to the right under Truss (‘jumped’ or ‘lurched are more accurate descriptions).

(Source: Financial Times)

Heady cocktail

Of course, some of the evidence fits several of these interpretations. Firing the head of the British Treasury department and then declaring that your Budget is a ‘mini-budget’, to avoid scrutiny, could be zealotry, or it could be cashing in, or it could be incompetence.

It’s probably doesn’t go with the ‘clever plan’ version, though, since the Treasury went along with years of Osborne’s austerity without kicking up a fuss despite the economic damage it was causing. (There are other views on the ‘clever plan’.)

My own view, briefly, is that it’s a heady cocktail of zealotry, corruption, and incompetence—that all three have interacted with each other to create the current crisis. You could even say that the current crisis is over-determined, because any two of these would have been enough.

Corruption

It is impossible to avoid the smell coming from the British government at the moment: the Chief of Staff who is of interest to the FBI, the Conservative billionaire hedge fund owner and Conservative donor Crispin Odey who used to employ the Chancellor who has made millions shorting the pound as a result of its collapse following the budget—with just a sniff of private information beforehand. Odey seems to have salvaged the fortunes of his hedge fund by doing this. Not to mention the Cabinet Minister and former (briefly) Chancellor of the Exchequer whose possible tax avoidance scheme continues to raise questions.

This list could go on, but it’s been a theme of the 2019 ‘Brexit’ government. The same corruption was seen throughout the pandemic procurement scandals.

As for competence, one of the signs of decline of a party is a shrinking pool of talent. The political talent pool has been shrunk more generally by the professionalisation of politics, but the Conservatives have accelerated this through expelling some MPs and by pushing through its pursuit of their ideological version of Brexit.

Running the country

In The Critic, Mike Jones brought these two ideas together when he noted a few months ago the shallowness of much of the Conservative leadership campaign:

For (leadership candidate Kemi) Badenoch, modern-day Conservatism is pretty much hollowed out, at least in terms of policy…“What’s missing”, she wrote, “is an intellectual grasp of what is required to run the country.” While Labour is cementing its image as the party of productivity and investment, the Tories, though unintentionally, spend much of its efforts in making the party as unattractive as possible.

But the deeper problem is that the party’s underlying ideas—legacies of that 40-year wave I discussed on Saturday—are about a smaller state with less public capacity. Hence Jacob Rees-Mogg’s persistent desire to shrink the civil service. A decade of austerity has stretched the capability of the state, of public services, and of local authorities to close to collapse.

State capacity

And one of the things we have learned, from the pandemic, from the climate crisis, and from the energy crisis, is that states need capacity if they are going to offer any kind of security to their citizens. Markets alone can not deliver this, even if they are well regulated. And they can no longer deliver growth either: we know, from the work of Mariana Mazzucato and others, that this requires all kinds of investment in public capacity.

Beinhocker and Hanauer described this as “middling out” economics, and it requires public investment:

a robust economy of thriving middle-income families is not a consequence of economic growth, it is its cause. So the policy priority is then to invest in the broad population of working people: education, healthcare, childcare, elderly care, worker training, affordable housing and good public infrastructure, from transport to broadband. It is also critical to support people with a living minimum wage and enough economic security that they aren’t economically trapped and can take risks, from starting a new business, to taking time out to reskill.

Johnson’s maverick style allowed him to nod in the direction of all of this, at least rhetorically, even if he had little intention of doing it. The political effect of Kwasi Kwarteng’s budget for the rich, along with Truss’ belated conversion to energy support, and the rolling crises that followed it, was to make voters realise viscerally—almost in a single day—how much they need the state to be on their side, to look after their security, in the 2020s.

A version of this article was published in two parts on my Just Two Things Newsletter.

Teaser photo credit: By Policy Exchange – Flickr: Kwasi Kwarteng, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30226087