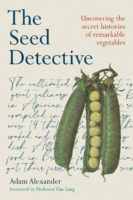

The following excerpt is from Adam Alexander’s book The Seed Detective (Chelsea Green Publishing, Sept 2022) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

The following excerpt is from Adam Alexander’s book The Seed Detective (Chelsea Green Publishing, Sept 2022) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

It’s All About the Colour

We have the Arabs to thank for introducing today’s carrot to Western Europe. There are two distinct sub-species that led to the domesticated carrot. The sub-species sativus, native to Turkey, was grown by the Arabs and much enjoyed by their invading armies, both animal and human. Over a thousand years ago, at the end of the tenth century, carrots are mentioned in a cookery book complied by Ibn Sayyār al-Warrā, an author from Baghdad. Called Kitab al-T. abīh ̆ (Book of Dishes), I imagine the book being added to the libraries of Europe’s Moorish invaders who had started their own vegetable gardens in the Iberian Peninsula early in the eighth century. The first historical record of carrots as a crop in Spain and southern Europe, however, is found in the work of the great Arab agriculturalist Ibn al-‘Awwām, towards the end of the twelfth century. It seems that by this time there were a number of different but unnamed varieties of carrot being grown.

Carrots came into cultivation in northern Europe some 200 years later and it would appear that they were valued for their high sugar content – recipes of the time have them being turned into jams, sweet condiments and puddings. Although they came in a variety of colours and shades – red, white and yellow – it was the yellow ones that became the most favoured in Europe because they were sweeter and didn’t turn a muddy brown when cooked. Carrot colour has been the subject of much scholarly discourse over the years and, whether the orange carrot existed before the attentions of Dutch breeders is explored later, so I use the word ‘yellow’ with some literary licence.

While Moorish invaders were introducing southern Europe to the western sub-species, sativus, its relative atrorubens spread further east from Iran and the Hindu Kush along the Silk Road. Modern genetic sequencing points to the fact that Chinese carrots, which come in red, white, purple and orange, are all derived from atrorubens. Similarly, deep red descendants of this branch of the family remain firmly part of the food culture of Rajasthan, a state in northeast India that was once controlled by the Moguls. The homeland of these Muslim descendants of Genghis Khan was in the heartland of the carrot’s birthplace. Coloured varieties are now becoming trendy in Western food culture, having been a staple in the East for centuries.

On a seed-hunting trip to India in 2019 I was able to enjoy freshly harvested carrots in the same way as if I had been back home in my own garden. The location was a small village, Jaisinghpura, half an hour’s drive southwest of the city of Jaipur in central Rajasthan on the eastern edge of the mighty Thar Desert. I had been hanging out with a bunch of farmers, all making a living from the land growing several desi (local) varieties of vegetables. One of them was Ramgilal. With his toddler son in his arms, he proudly gave me a guided tour of the 30-acre (12-hectare) farm he shares with his two brothers. We were in his carrot patch, and he pulled a long, large, deep red specimen from the sandy soil. I wiped it on the seat of my trousers and bit into the sweet, crunchy flesh. This is a carrot I had seen being sold in markets everywhere on my travels through the state. It’s the one everyone eats, a mainstay of Rajasthan’s indigenous food culture. It looks spectacular, a beacon on any market stall, and eaten freshly pulled, it was something divine.

The Colour Orange

Columbus’s arrival in the Caribbean in 1492 sparked a transfer of native vegetables in both directions across the Atlantic. Carrots could be stored for long voyages and were planted by the colonisers who followed him. However, it was not until the beginning of the seventeenth century that the carrot was to undergo a dramatic change of fortune, in more ways than one. As the sixteenth century drew to a close, Flemish growers started to work on improving the colour, yield and appearance of the carrot as well as its eating quality. Yellow, western varieties, being biennial, were not only less likely to bolt than their eastern cousins, but also genetically predisposed to grow a single bulbous root, full of sugars and flavours. The darker the yellow, the more breeders liked them.*

The word ‘orange’ is relatively new to the English language and first appeared in a reference to clothing belonging to the Scottish Queen, Margaret Tudor, in 1502.1 The orange, which is native to China, arrived in Europe with the Arabs at the beginning of the eighth century and was called the sinaasappel (Chinese apple) in Dutch. The Spanish took the Persian word for the fruit, narang, referring to the bitterness of its skin, and called it naranja, which in Old French translated as ‘orange’. The 2011 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary describes the colour orange used in Old English as g.eolurēad (yellow-red). This name for the fruit was probably adopted into Middle English at the same time as the orange first appeared in Britain after the Norman Conquest in 1066, but it was not used to describe the colour of a carrot until much later. So, it is not surprising that descriptions of carrots of all shades of yellow and red didn’t describe them as ‘orange’ until the word became a common adjective in sixteenth-century English. Because of this, earlier descriptions fail to help the researcher achieve clarity as to a variety’s true colour.

Although principally red carrots were being cultivated across Europe from the eleventh century, it was thanks primarily to highly selective breeding by the Dutch that 500 years later the orange carrot we recognise today became ubiquitous. As a kid I was told that the orange carrot was a symbol of the Dutch Royal House of Orange. It was used as a propaganda tool when William and Mary took over the British throne after a bloodless coup in 1688 known as the Glorious Revolution. William inherited the title of sovereign Prince of Orange after a feudal principality, complete with orange groves, in Provence, southern France. Sadly, the story that breeders created an orange carrot to honour the Dutch royal family is pure myth, but since when has fact been allowed to interfere with political propaganda? The reality is that the Dutch were growing orange carrots long before William inherited his title and moved to England. But the orange carrot is the national vegetable of the Netherlands and many of its people still cling to the idea that its colour was created as a tribute to the House of Orange. As a marketing strategy and way to raise ‘brand awareness’, it was brilliant, and I think it would be churlish to disabuse them of their belief. Also, now that the genome of the carrot has been unravelled, we know that orange carrots are the direct descendants of yellow varieties and are testament indeed to the genius of Dutch breeders.

A Long-Lasting Heritage

Carrots had become part of a subsistence diet throughout Europe and the Americas by the seventeenth century, but different varieties were yet to be given names. A seed seller from London, William Lucas, lists red, orange and yellow carrots in his catalogue of 1677 and, although Dutch breeders had named varieties, these were not shared with consumers for another hundred years. At the end of the eighteenth century, English merchants at last listed a few named varieties. The Curtis seed catalogue of 1774 includes three: Early Horn, Short Orange and Long Orange. In 1780, J. Gordon of Fenchurch Street lists just two carrots: Early Horn and the Orange or Sandwich carrot (Sandwich refers to where they were grown). Carrots like to grow in a light soil, and Sandwich in Kent fitted the bill perfectly. Flemish immigrants escaping Catholic persecution in the latter half of the sixteenth century had settled there and grew them, including for their new Protestant queen, Elizabeth I. We also know that Early Horn is one of the oldest named varieties and is related to many of those we enjoy today.

Not only do we have to thank Dutch breeders for the ubiquity of the orange carrot, but it is also to a Dutchman, O. Banga, writing in the early 1960s, that we should give thanks for a considerable body of work on the history of carrot cultivation and breeding.2 He identified two Dutch varieties, Scarlet Horn and Long Orange, as being the progenitors of pretty much all of today’s orange carrots.

Through genetic analysis we now know those purple carrots that originated in Afghanistan mutated into yellow ones. Also, we need to remember that descriptions of carrots as being red actually describes those coloured purple – think of red cabbage and red beetroot. Colour changes of the earliest cultivated carrots happened through accidental mutation, rather than hybridisation. The Western Europeans’ preference for the yellow over the purple carrot was encouragement enough for those eighteenth-century Dutch breeders to work on ever-deeper yellows until they got a sweet and tasty orange the consumer would buy. By the middle of the eighteenth century, we had new varieties: Early Half Long Horn, Late Half Long Horn, Early Short Horn and Round Yellow; the last two being the parents of nineteenth-century classics, Paris Market and one of my favourites, Amsterdam Forcing. It is testament indeed to the quality and skills of breeders that these two early varieties continue to be hugely popular after over 250 years in cultivation. Other carrots such as Nantes types – those with cylindrical roots – were the result of a century of breeding from the now extinct cultivars Late Half Long Horn and Early Half Long Horn. The name suggests the French had a hand in developing this type. Early twentieth-century breeders, according to Banga, gave us Imperator – a long, tapering type, which is a cross between the Nantes and Chantenay, a red-cored variety (delicious by the way) that had been bred from another eighteenth-century variety called Oxheart. Imperator types are the basis for most modern cultivars developed for today’s supermarket trade.

One variety that I grow every year is Autumn King, an open-pollinated stalwart that has been around for a century or more and, thanks to climate change, one that can sit happily in the soil through the winter to be harvested as and when required. The days of clamping – storing carrots in mounds of sand – are well and truly over, for me at least. The prettily named Flakkee, a very good overwintering storage variety, has claims to Italian heritage. It is synonymous with Autumn King, which begs the question: do we have here another example of breeders renaming varieties to suit their own markets and cultural sensibilities? Fortunately, many of these very earliest breeds of carrot are still with us and, regardless of what they are called, they are a culinary delight.

* The red carrots, which are descended from the Eastern parent I enjoyed in Rajasthan, are annuals. A few prime specimens are left to go to seed after the crop is harvested. Western carrots are biennial, the result of domestic selection, which allowed farmers to lift and store them through the winter. Selected roots would then be re-planted in the spring to be allowed to go to seed. Carrots are not the only biennial grown by gardeners. Many other root crops like beetroot and parsnip are also biennial, as are onions and some brassicas.

References:

- Kassia St Clair, The Secret Lives of Colour (London: John Murray, 2016): 88.

- Banga, ‘Origin and Distribution’: 357–70.