Geopolitical risk took center stage last week when Russia announced it would annex the Ukrainian territory it has seized—after holding “referendums,” of course, in those areas. Any attack on what would now become Russian territory would be met by all means necessary including nuclear weapons. Presaging this development, I wrote the following in a piece from March entitled, “World War III is here, but it’s not what we expected”:

[I]f Russia ultimately feels backed into a corner, the Russian leadership may see no alternative but to draw its main competitors into a wider war with the hope of instilling enough fear of a nuclear confrontation that both sides relent and a political settlement and security guarantees follow that include an agreement to end all economic warfare.

It is in just such circumstances that both sides may miscalculate or may misconstrue the words of the other and choose to escalate the conflict in a way that will make prophets out of all the screenwriters and novelists who depicted World War III as the end of civilization.

It seems “such circumstances” have arrived and both sides are choosing escalation. I am not predicting “the end of civilization.” But I’m more worried than I was a week ago.

Meanwhile, the world economy appeared to be slowing as central banks increased interest rates to rein in inflation. Such rate hikes have little hope of solving logistical bottlenecks or outright shortages of key food, energy and mineral commodities. But the hikes do risk setting off an uncontrolled wave of derivatives-related chaos and deleveraging across the highly indebted world economy.

First, let’s deal with Russia-Ukraine conflict.

I expect Ukraine to test this nuclear threat with the help of NATO armaments and supplies. While the Russian military had hoped for a quick defeat of Ukrainian forces followed by a peace agreement on terms favorable to Russia, Russia is now locked in to what appears to be a long war of attrition.

Battles of attrition usually are won by those who can absorb the most losses without collapsing. Ukraine’s economy has been shattered. So, why wouldn’t the Russians win such a war? The answer, of course, lies in the fact that Ukraine is not alone. It is receiving military assistance from a number of countries, several with economies larger than Russia’s including the United States, Germany, United Kingdom, France, and Canada. Australia, which has an economy not much smaller than Russia’s, has also provided military aid to Ukraine.

Since these countries have all committed to help Ukraine repel Russian forces and regain Ukrainian territory, it’s hard to see how Russia could withstand a years-long effort by these countries to keep Ukraine competitive on the battlefield—despite Europe’s loss of cheap energy supplies from Russia. Russia’s economy is smaller than Italy’s. While its military is certainly formidable and armed with modern weapons, it’s hard to see how the Russian economy could outproduce the combined supporters of Ukraine when it comes to military materiel.

So, it seems inevitable that at some point in the future, Ukraine will regain some of the lost territory which Russia will shortly annex. And, Russia has told us that that outcome will be considered an attack on its homeland and be met with all force necessary including nuclear force.

Not surprisingly, Ukraine and its friends in NATO do not want to give in to nuclear blackmail. That would be a green light for any country with nuclear weapons to seize territory and secure its gains by threatening nuclear retaliation against anyone who dares to try to take the territory back.

So, it seems at some point Russian nuclear threats will be tested. If the Russians lose any territory they have occupied in Ukraine, especially if they seem to be losing it permanently, will they fight back with nuclear weapons? If so, will NATO forces supply nuclear weapons, perhaps short-range ones, to retaliate? Or would NATO actually step in itself? Would Russia decide to respond with a nuclear strike on, say, a town in Poland?

Perhaps the Russians are bluffing. If someone tells me he or she is not bluffing—as did President Vladimir Putin in his statement announcing the nuclear threat—I’m inclined to believe that that person is, in fact, bluffing.

But we will not know for sure until the right conditions prevail and the Russian military is forced to demonstrate that either Putin was serious or that he was, in fact, bluffing.

All of this is taking place against a backdrop of slowing economic activity due in part to logistical snarls caused by the pandemic and now by economic sanctions against Russia. High energy prices worldwide and sheer lack of energy in Europe are also threatening economic growth.

Amid these problems the world’s central banks are raising interests rates to rein in inflation. Shortages of key food, energy and mineral commodities are the main causes of inflation and can’t really be addressed by interest rates.

Central banks around the globe continue to signal their resolve to beat inflation by raising interests rates even higher. High interest rates, of course, tend to dampen economic activity by making the cost of borrowing more expensive.

The problem as I and many others see it is that these banks will keep raising rates until something in the fragile, overleveraged world financial system breaks—and possibly creates a chain reaction of defaults and financial failures that cannot be halted until a huge amount of damage has been done. Much of this fragility is arising in Europe as more and more businesses are brought to the brink by wildly escalating energy prices.

The combination of emerging geopolitical instability and financial fragility provide the makings for an exciting and distressing autumn.

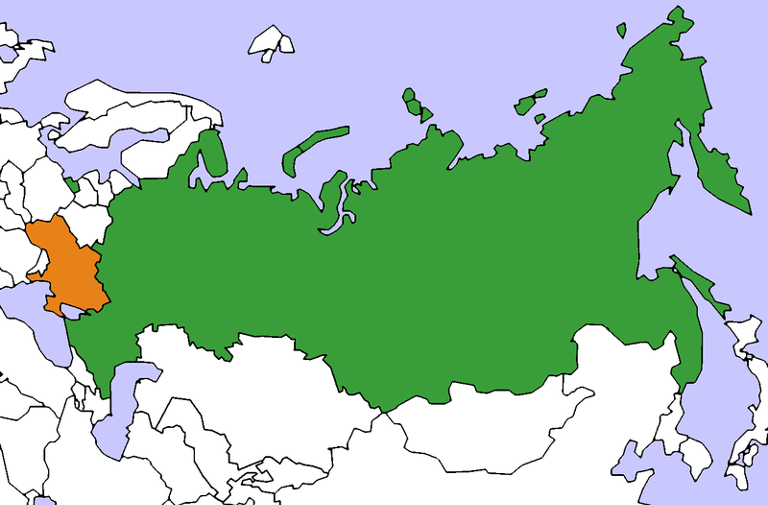

Graphic: Russia Ukraine Locator (2006). Probable creator Aris Katsaris. Via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Russia_Ukraine_Locator.png