Into the light: on exiting not just the figurative but the literal cave…

The mental and physical benefits of spending leisure time outdoors are well documented but, writes Rupert Read, we need more of it during school and ‘work’ hours too.

“You ‘green types’ want us all to go back to living in caves…”

If I had a pound for every time I have heard this…well, let’s just say, I could afford a very big cave indeed.

Although, of course, as a ‘green type’ sitting inside our ‘caves’, as our homes seem to have become, is the last thing I actually want – especially during a pandemic when it was much safer to be outside, as government regulations reflected to some extent.

However, I believe we could have gone much further during the last couple of years and we would have benefited so much from doing so. By failing to get outdoors enough, we have allowed literally tens of thousands of people to unnecessarily die.

Take schools; lessons could have moved outdoors and in doing so they would’ve prevented so much of the infection that has let rip through our classrooms and gone on to affect many parents and grandparents very badly.

I can already hear some of you commenting that the British climate makes this, in effect, impossible. Well, reader, I can promise you that it does not. I co-taught classical philosophy outside, as part of my day job in the University of East Anglia, while virtually all my colleagues were lecturing online, 18 months ago.

Even during the winter, students wrapped up warm and we had one or two places where we could take shelter if we were affected by rain or indeed snow as on occasion we were.

When the weather was better, in the finest tradition of the ancients we sometimes engaged in peripatetic philosophy – in other words we walked around the beautiful and striking UEA campus and stopped periodically to engage in philosophical discussion.

That discussion was often enriched by the outdoor location we were in: I took examples from the natural and not so natural world around us to illustrate points that we were discussing.

My university was forward-sighted enough to create a couple of bespoke outdoor venues to be used as classrooms, basically giant open tents, but I was discouraged that they weren’t used by more of my colleagues.

Too many seemed happy to remain online, happy to stay in the cave. How disappointing, especially for philosophers.

Of course, probably a few of them had to remain online, either because they have dependents at home or perhaps are more vulnerable or live with someone more vulnerable and didn’t want to run the risk. But where were the great majority? Online by choice, or simply not perceiving the possibility of taking philosophy outdoors, as my colleague Catherine Rowett and I did.

There has been much talk of creating expensive ventilation systems but little action.

But why not take the most obvious action of all: get outside more, where it’s always ventilated?!

If Forest Schools can do it, and if I can do it, then nearly all of us / all of you can do it…

Downing Street, disgracefully, held parties out of doors during the worst periods of the pandemic, when such occasions were banned for mere ordinary mortals. They used the pitiful excuse that those parties were actually work. But here would have been a valid alternative: if they had actually decamped outside more for work, held real meetings (rather than booze-ups) outside where and when feasible, that would not only not have been a hypocritical disgrace: it would have exhibited leadership.

Imagine how it could’ve been if in universities, schools and other institutions and, indeed, where possible businesses around the country everything that conceivably could’ve been done out of doors was done out of doors.

We would’ve escaped many infections and deaths from the pandemic and we would’ve benefited, of course, in many other collateral ways: from getting more Vitamin D to encountering more nature, from exercising more to escaping the often cloying and overly dry atmospheres found inside too many of our buildings.

This begs the question why is it so hard for us to get outside of the cave? Let me give another anecdote from my academic life, which might help to explain why I think we get stuck inside.

Once upon a time many years ago I was in discussion with a number of UEA colleagues about the future of postgraduate teaching and supervision at our university.

Meanwhile, outside and plainly visible through the large windows in the room, we were in a tremendous thunderstorm, which brewed and then unleashed over the campus lightning strike rapidly followed lightning strike. I wanted us to stop and look (actually, what I really wanted was for us maybe even to go outside and fully experience it).

However, I was astonished to see that most of my colleagues didn’t seem to even notice the amazing show that nature was putting on, they just carried on with their academic discussion without batting an eye.

This, to me, was a clear example of the enormous disconnect that our civilisation has created between ourselves and the outside natural world.

If even thinking people – or perhaps especially thinking people – find it hard to take a moment to sit and stare, to wonder at the wonders of this world, then, frankly, what hope is there for our civilisation?

I am confident that this civilisation is coming to an end (This Civilisation is Finished by Rupert Read and Samuel Alexander). It will be replaced by a civilisation, in all likelihood, that is much better at grounding itself in the Earth and much more attuned to that natural world.

We need to make that civilisation succeed this one as quickly as possible and part of how we do that will be through re-accustoming ourselves to being outside more.

As I already hinted earlier, in doing this we will also revive a grand old tradition in philosophy. In the ancient world, it was normal for philosophy to take place outside and, indeed, many of Socrates’s most famous historical moments and dialogues occurred while walking or in the street or the agora. (Yes, again, I know that the climate in Greece is kinder to this than that in the UK; but they, of course, did not have such good access (as we do) to amazing technologies such as thick anoraks…)

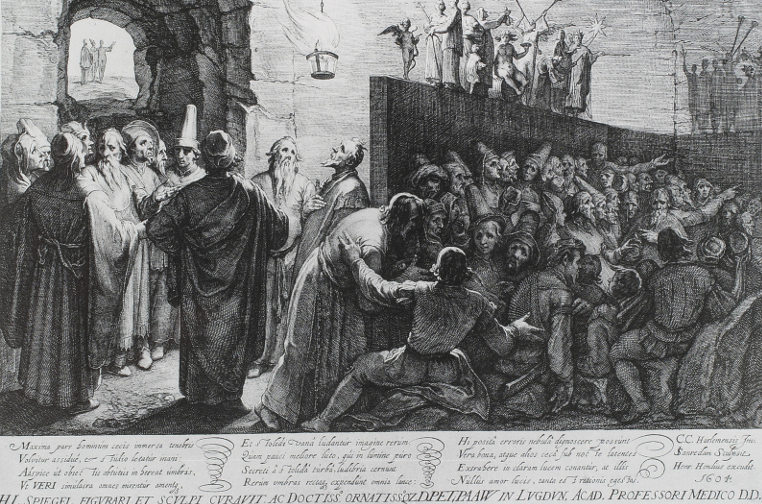

I don’t believe it is fanciful to think that there may be a connection – a connection with peripatetic and more generally OUTDOOR philosophy – with Plato‘s tremendous allegory of the Cave. He held that it was as if we are stuck inside a cave facing shadows on the wall, not realising that they are only shadows and not realising that we can turn up get up turn around and walk out into the light reader.

That is what I am recommending that you do and we do.

Let us literalise Plato’s founding philosophical allegory. Let us go into the light.

The coronavirus should serve as a wake up call, it should prompt us to move much more thoroughly out of our caves and into the great outside world, but that move is over-determined – we need it anyway for numerous reasons that I have gestured at in this little piece.

Our children’s children will live much more outside, much closer to the land. Many of them will almost certainly be much more involved in food production than most of us are today, but the sooner we start moving in that direction the less damaged our earth will be. The happier our own lives will be.

What’s not to like? It is what I call the ‘beautiful coincidence’: that the very things that we need to do in order to mitigate the climate crisis and stop destroying nature tend to be the very things that we need to do in order to actually make our lives better, healthier and happier.

It really is high time that we turn around — and exit the cave.

Teaser photo credit: Plato’s allegory of the cave by Jan Saenredam, according to Cornelis van Haarlem, 1604, Albertina, Vienna By Jan Saenredam – British Museum https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1852-1211-120, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4040982