Ed.note: You can find Part 1 of this interview on Resilience.org here.

How do we develop vibrant local economies that are good not for the shareholders of a corporation headquartered in some distant state, but for the people who actually live in the neighborhood?

This is a crucial question for advocates building stronger, more resilient towns and cities. To help answer it, I recently interviewed Dave Kresta, an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Portland State University, where he teaches courses in the school of urban studies and planning.

With a background in computer engineering as well as an MBA, Kresta worked for years in the tech industry. As his job drew him more into business and strategy development, he began looking at deeper social issues, including poverty, gentrification, and the lack of affordable housing. “These are complex problems,” he said, “and from an intellectual perspective I was intrigued.”

Yet his interest was more than just academic. “I grew up with a strong faith as part of my upbringing,” he told me. “For the first part of my life, faith was more of a private thing, separate from what’s going on in the world around us.” But that was changing. Kresta felt called to help other people of faith understand the complex problems he was exploring, and then figure out how they can contribute to solving them. He returned to Portland State, earning a PhD in urban studies in 2019. His dissertation was on the impact of churches on neighborhood change, especially their economic impact.

In addition to teaching, Kresta is a Fellow at the Ormond Center at Duke Divinity School. As a consultant, he helps faith-based organizations partner with neighbors to build more vibrant, just, and equitable local economies. Last year, he released his first book, Jesus on Main Street: Good News through Community Economic Development.

In Part 1 of this interview, I talked to Kresta about the important differences between traditional economic development and Community Economic Development. We also touched on the role faith communities play in the local economic ecosystem.

Here in Part 2, Kresta and I talk about the practical ways faith communities can help build local economies, about gentrification, and about how (and why) to build bridges between faith communities and economic development leaders.

PATTISON

I want to talk about (your concept of the) economic ecosystem next. You write that a healthy Community Economic Development ecosystem involves many different sectors. And the book includes a powerful toolkit that lays out, I think, 10 different aspects of that ecosystem as well as the role faith communities can play in them. If it’s okay with you, I’d like to explore a few of those in detail, while encouraging people to check out the book. Not only can they go deeper on these few, they can go broader on the ones we can’t get to: makerspaces, local cooperatives, workforce development, and much more.

Let’s start with microbusinesses. These are businesses that have revenue of $100,000 or less, and five or fewer employees. These are small businesses and yet, as you talk about in the book, they play an outsized role in the economy. Why can a microbusiness strategy be so powerful? And then, what’s the potential role of churches there?

KRESTA

Microbusinesses are powerful and a great place to start because there’s already probably quite a few of them in and around your neighborhood. You just might not see them. The barriers to entry are fairly low, so you don’t need to come up with a lot of capital or get an MBA. And you can tap into—and this is particularly important, as in immigrant communities—an entrepreneurial spirit that’s embedded in a lot of people already.

One of the biggest benefits as an economic development strategy is that microbusinesses bolster the local ownership of assets. So, it not only provides goods and services to a community, but those goods and services that are purchased, they stick around. That money, that capital, stays in the community. That’s why it’s so important to have local ownership be a critical part of a Community Economic Development strategy. My book mentions a few other larger types of local ownership, including larger businesses and worker cooperatives, but microbusinesses are a great first stop.

There is a wide range of ways faith communities can get involved. Many churches have plenty of people with experience in a variety of types of businesses. So there’s a role for coaching and mentoring, even just with the mechanics or the logistics of launching a business.

Churches can provide connections and networking opportunities. Being aware that this microbusiness is providing such-and-such service or good. And maybe connecting them with a larger business in need of what they provide. Creating supply chain or value chain connections.

Churches can provide space, too. That can often be an issue when starting a business: Where do I have my office? Where do I keep my goods, warehousing? Faith communities may be able to help.

PATTISON

There’s another one, and I think many of our readers will be interested in this: commercial district revitalization. By commercial district, you’re not referring just to a walkable, downtown area. You’re talking potentially about strip malls, empty spaces that used to hold big box stores. You’re talking about commercial districts very broadly. What are some things that faith communities can do here?

KRESTA

First off, it’s drawing attention to potentially forgotten places. We would all love to have a walkable, historic commercial district with a gazebo and a fountain. The reality is, with our suburban sprawl, we’re stuck with a lot ugly commercial areas in various stages of vacancy or abandonment. If you’re a religious congregation in the neighborhood, and you love that neighborhood, and you drive by a corner, and it’s empty or the parking lot is a haven for criminal activity—your immediate thought needs to go to, “What does it mean for that place to be healed?”

I think churches can start that thought process practically. I gave examples in the book of churches who raised capital and donations and got loans, and either purchased or leased buildings that had been abandoned. They renovated them and are opening them up for local businesses to move into. Faith communities can be a kind of “first mover,” the pebble to get things moving again. A space like that may not be financially viable for a developer when they compare it to their other opportunities. But if you, as a church or a faith-based community, are committed to that specific place, then it makes more sense. It’s more of a triple bottom line approach as opposed to just looking at the financial.

PATTISON

Dave Kresta’s book, Jesus on Main Street. (Source: Amazon.)

In Jesus on Main Street, as well as in your dissertation, you write about the factors contributing to gentrification. What are some things we need to keep in mind so that we’re building an economy that benefits the people who live there rather than displaces them?

KRESTA

Many of the same principles that apply to Community Economic Development as a whole should be part of an anti-displacement, anti-gentrification strategy. Equipping people with local ownership of their own businesses will go a long way for those business owners and keeping that money local. Wealth building activities are critical. How you help people start their own microbusinesses or larger businesses is a critical factor.

Affordable housing is another thing. I have a whole chapter on this. If housing prices skyrocket, that’s just going to displace people, which obviously goes against the principles of Community Economic Development. So another strategy is preserving affordable housing and encouraging the building of more affordable housing. Some churches are actually getting involved in repurposing their buildings or their space to build affordable housing as well.

PATTISON

Chris Smith, my Slow Church co-author, wrote an article for Strong Towns a couple weeks ago about the community development corporation his church started. He talked about how they turned an old school property across from their church into 32 units of affordable housing

KRESTA

One other thing I’ll mention about gentrification. When people hear gentrification, they think of the residential part of it. But there’s also commercial gentrification: How can we serve local people with local businesses?

PATTISON

Something we talk about a lot at Strong Towns is the importance of humbly observing where real people are struggling in real places and in real time. Then you draw from what you have and build on that to address those struggles. One of my favorite case studies from your book is the Church of the Messiah in East Detroit. I believe the pastor’s name is Barry Randolph, right? Talk about holistic—the breadth of what they’re doing is pretty amazing.

KRESTA

I’ve collaborated with him. And I met him the first time when we did a CCDA workshop in Kansas City in November. He is just an amazing guy. But it’s an amazing community as well. I encourage you to reach out to him or I can connect you; he’d be a great person to interview. He takes the ideas that people have in the community and equips them and makes things happen.

One thing I was just totally blown away with is their fearless approach, not feeling bound to what a church can get involved in. So they do internet service provision, for example, because that’s a real need in the community and it impacts people’s ability to thrive. They’ve helped a number of people launch businesses, providing them space. They do workforce development. I included Church of the Messiah as my capstone case study because they view it as a holistic approach as well.

I try to make this point in my book: You can’t just look at this as, “Hey, we’re going to do one program and we’re going to solve the economic challenges of our neighborhood.” You may have to focus on only one program, and that’s fine, but you’re darn well going to have to connect with other people doing other types of programs. So if you’re doing a microbusiness program, you may want to connect with someone doing a business incubator, for when those microbusinesses are ready to grow. If you’re doing workforce development, you better connect with the employers in the neighborhood and connect to other people doing programs. Remember, it takes a whole ecosystem approach.

My takeaway from the Church of the Messiah is that they built this ecosystem from the ground up because there was nothing around them.

PATTISON

I listened to an interview you and Barry gave and he talked about how when someone signs up for internet, it’s somebody from Church of the Messiah who comes out and installs it. That’s such a great image.

KRESTA

Yeah.

PATTISON

Last couple questions, moving into the very practical. First, what are some practical next steps you would give to a church, synagogue, mosque, or another community of worship, to begin exploring Community Economic Development?

KRESTA

You need to find a group of people that share this burden for economic justice, for healing in your community. That could be people within your church or faith community as well as people outside of it. So, I’d say that’s the first step: finding people that share this desire and this vision for economic thriving for all.

Then start educating yourself. Research the different aspects of Community Economic Development. Listen. Take an inventory. I provide a number of worksheets in the book, adapting asset-based community development specifically to Community Economic Development. Ask, who’s doing what in the community and who’s falling through the cracks? Who’s not being served by the existing programs?

If you follow those steps, find a group of people, start dreaming together, start educating yourselves, start listening and identifying gaps in the community and assets in the community, then I think you’re at that point where you can actually start thinking seriously about, “Okay, which of these Community Economic Development toolkit strategies do we want to take on first?”

PATTISON

Your book is very practical. It’s packed full not only of information and case studies, but also assessments and worksheets. My own first step recommendation is for people to get the book. There’s so much in there. My final question is whether you have any tips for people who are already engaged in Community Economic Development. Specifically, what advice would you give them to reach out to local religious groups to explore collaborating?

KRESTA

Just recognize there are churches who are interested in this. I won’t say all churches but a growing number. I guess it’s a matter of reaching out and finding those churches who are. Sadly, they’re also going to run into churches that are too busy, can’t do it, or aren’t interested. Look for those churches that are hosting a faith and finance class or a workforce development class. That’ll give you an idea of who is at least interested in this more holistic discussion.

It’s not very efficient for a local economic development leader to have to call all these churches to find out who wants to work with them. Hopefully they are the ones who start getting contacted by churches. This is part of my goal, part of my dream.

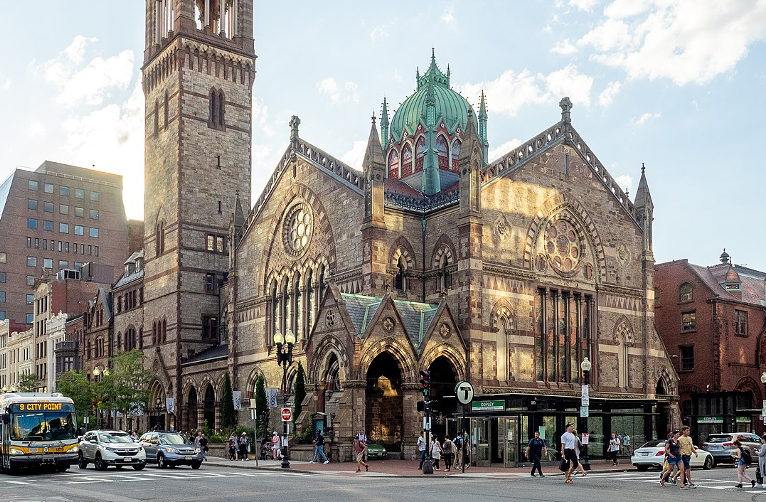

Teaser photo credit: By Ajay Suresh from New York, NY, USA – Boston – Arlington Street Church, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82156221