I wouldn’t normally be straining myself to get a post out on New Year’s Day, but (checks archive) blow me if today isn’t the tenth anniversary of this blog’s inception. Three hundred and fifty blog posts. Ten thousand comments. It’s quite some wordage. Has it all been worth it? I couldn’t possibly say, but I hope the landmark is enough for me to be forgiven the self-indulgence of a short trip down memory lane.

When I started the blog I was four years into my tenure as the main grower for Vallis Veg, the small local veg box scheme that I’d started with my wife (along with two other people working on the retail side). And I was four years past the last rites on my academic career. In the early years of the box scheme we sent out a printed newsletter to our customers with the boxes every week in which I sublimated my writing aspirations with reflections on the state of the world from my vantage point behind the wheel hoe. When we switched our website over to WordPress and my friend Steve suggested I might write a blog instead of a printed newsletter, smallfarmfuture.org.uk (or, at least, its forerunner) was born.

At the outset, I’d intended the blog essentially to be a replacement for my customer newsletters, but it quickly took on the form of a wider attempt to consider the ecology and the politics of a contemporary human culture and agriculture that, as I saw it, had gone seriously awry. In those early years, I was interested in debating different agricultural systems – especially now that I was working on them in real life rather than absorbing the secondhand wisdom of various alternative agriculture gurus. I also wanted to better understand why it was so difficult to make small businesses geared around renewable local agriculture work. At the same time, and relatedly, we were locked in a battle with our local council to be able to live on the land we farmed. Quite a lot hung on the outcome, in terms of whether my decision to quit a steady, well-paid job would turn out to have been a stroke of insane genius, or merely insane.

Around that time, I read Stewart Brand’s book Whole Earth Discipline and picked up the vibe of other renegades like Mark Lynas and Mike Shellenberger as they recanted a broadly left-wing, anti-capitalist environmentalism in favour of the kind of ‘green growth’ mainstream sustainability narrative that’s now common coin (at least Brand and Lynas only trumpeted their conversions once – Shellenberger does it with monotonous regularity, though I’m not sure he was ever really in the left-green camp he now repudiates). I found this ‘eco-modernist’ position, as it’s now rather problematically called, unconvincing and superficial, so I started engaging with it on my blog.

These early emphases have now faded somewhat. I’m still interested in farming methods, but I’ve come to the view that the main problem is not how people farm but how people organize themselves economically and politically, and if we get these latter right then the former will pretty much sort itself out in the long term. I’ve also become less interested in commercial agriculture and more interested in non-commercial horticulture, smallholding or homesteading, where online resources are already legion. Plus I’ve found that practical discussions seem too often to degenerate into the “you don’t want to do it like that” space, typically without the discussant troubling themselves enough to find out exactly how and why you are doing ‘it’ like ‘that’. So practical homesteading matters are likely to remain at most an occasional sub-theme here.

As to eco-modernism, my critique of The Eco-Modernist Manifesto co-authored by Brand, Lynas, Shellenberger and others considerably increased my readership, but my interest in engaging with it and indeed in engaging with most of the shouty, finger-pointy argumentation that passes for public intellectual debate these days around eco-modernism and much else besides has considerably decreased. I don’t think it gets us closer to solving contemporary problems, so I’ve tried as best I can (without complete success) to take my writing in different directions. Happily, enough people have found it illuminating for it to seem worth persevering with.

Talking of solving problems, one issue of concern to me on this blog has been our over-easy recourse to solutionist thinking in modern society. This applies of course to mainstream technocratic solutionism of the kind that considers our energy problems soluble via nuclear power, or our food system problems soluble via GM crops or industrially manufactured eco-gloop or whatever. But it also applies in the alternative farming or economics worlds. One part of this blog has involved articulating a scepticism towards off-the-peg ‘alternative’ solutions, whether technological or social. Although I might now frame it a bit differently, I was pleased on this front to get my critical review of perennial grain cropping into a peer-reviewed scholarly journal, somewhat prompted by an unpleasant exchange with an especially combative permaculturist. This was one of three peer-reviewed articles on farming and environmental issues I’ve published since quitting academia for the independent scholar’s garret. I doubt there will be any more.

Then came 2016, the year of the Trump and Brexit votes, widely heralded in certain over-excitable circles as much needed body blows to the complacent liberal capitalist global order. I didn’t think they were. Or, if they were, they weren’t very good ones. Perhaps I spent too much time on the blog dwelling on the politics around this, in particular on how fascist it was. To which the answer has turned out to be certainly a bit. It’s easy to dismiss such events as just the surface fizz of media politics, irrelevant to the deeper beats of nature, climate and energy that are the real drivers of contemporary human affairs and that are more deserving of attention. But as those beats get more disturbed, so does the politics – and ultimately it’ll probably be the politics, that is to say our organizational responses to biophysical crises, more than the crises themselves that will do for many of us.

Anyway, I guess the result of 2016 was to redouble my efforts to find an ‘alternative’ alternative politics and economics to both mainstream orthodoxies and the sham insurgencies of that year. This has been the main focus of the blog since then. It’s not a case of finding the right political economy, cueing the drumroll and then summoning it to save a grateful world. No doubt there will be more Trumps, Farages and Putins, and more neo-Bolshevik aspirants to the crown of world government burnished by the technocratic left. But there may be opportunities for deeper and more plausible forms of grassroots renewal on small farms and in small towns around the margins of this ossified megalo-politics, and my hope is that this blog has contributed in however small a way to clarifying those opportunities.

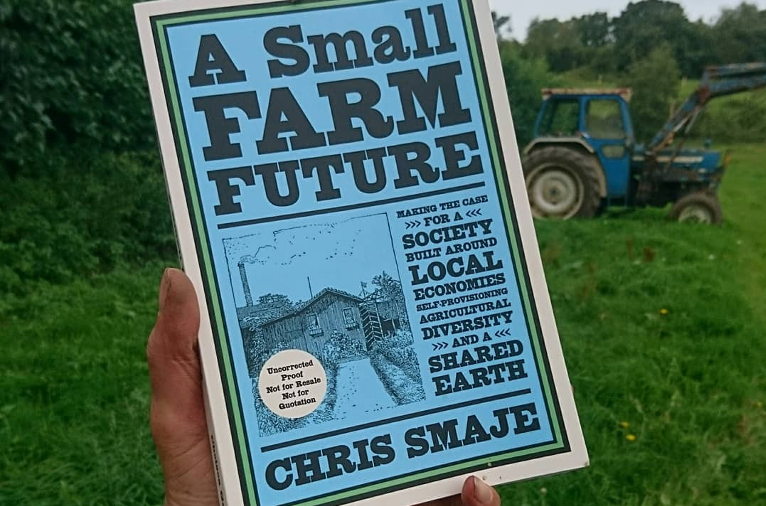

I wrote a couple of blog cycles in relation to that project. One on the Peasants’ Republic of Wessex where I looked at possibilities for local production of food and fibre in my region, and another on the History of the World in 10½ blog posts where I tried to put the politics into a larger context. Both of these, and many other strands from this blog, fed into my book, A Small Farm Future, published by Chelsea Green in 2020, which has been one tangible product of the blog that’s now out there making its way in the world.

I like to think that acquiring a smattering of scientific and political knowledge from an orthodox mainstream education has protected me from certain excesses typical of the dissenting autodidactic blogger, though perhaps hasn’t immunised me completely. In particular, a background in traditional left-wing and Marxist analysis has helped shape my worldview in ways that I still consider positive, but I find much of the analyses emerging from those traditions today too stuck in the ossified megalo-politics I mentioned to address current issues convincingly.

To my mind, this megalo-politics, and the orthodox educational canon associated with it, hasn’t kept its eye on the ball in relation to the politics appropriate to the current moment, and has badly erred by marginalizing, silencing and ridiculing other traditions and ideas more grounded in immediate material livelihood, the local and the sensory – such ideas and movements, for example, as agrarian populism, Romanticism and distributism. I’ve found myself sort of inventing an alternative political economy for myself along these lines, only to find that I was tapping into rich traditions of thought paralleling my own that previously I’d only dimly been aware of, or didn’t take seriously enough, because orthodox political thought didn’t take them seriously enough.

I’d long sought escape from Marxism and traditional leftism without quite finding a home elsewhere. Looking back on it, I think my book and this blog signal that uncertainty. But I’m now clearer about how to ground an alternative political economy and I hope I can develop that in the future. The stinker of a review my book got from a couple of Marxist bros stung me at the time, not least in its rank unfairness, but now seems almost like a necessary rite of passage into a less totalizing and more engaged worldview. Part of that involves an increasing interest not so much in arguing what the right politics are, but in how to deal with arguing over what the right politics are.

A few years back I wrote a sardonic post about how neither of my career choices – farmer and writer – were wise picks for turning coin, and I light-heartedly added a Donate button to the website to underline the point. It came as a pleasant surprise a couple of months later when somebody actually dug into their pocket and contributed. Since then there’s been a small trickle of donations to the site for which I am most grateful.

I get plenty of requests to place pre-written content for money or to monetize the site through advertising, which so far I’ve resisted (to be fair, most of them are probably just spam). Since I published my book, the contributions have dwindled. So I thought I might just mention that the book hasn’t exactly made me rich. In fact, one of the few jobs I’ve done that’s paid a worse hourly rate than writing this blog is writing my book. The truth is, I’m a very lucky human being and I don’t – at the moment anyway – need people’s cash to keep the wolf from the door. Undoubtedly there are people much more needful of your money than me. But if you’ve found any of my writing over the last ten years helpful or informative in any way, maybe you’ll consider a small donation so that I can at least scrape together a few coins and buy a bottle of something bubbly to celebrate ten years of smallfarmfuture.org.uk.

As to the future, who knows? I have a blog cycle about my book to finish, various other themes to share and a farm and burgeoning farm community to contribute to. Plus a growing anxiety about where humanity is headed. But definitely some good memories from a decade of engaging with other humans on this blog. Many thanks for the comments and debates here, from which I’ve learned a great deal.