Democracy Rising is a series of blog posts on deliberative democracy: what it is, why it’s powerful, why the time is right for it, how it works, and how to get it going in your community. The series originates in the United States but will discuss principles and draw upon examples from around the world. Views and opinions expressed in each post are those of the individual contributor(s) only.

A common notion about the rise of civilization goes something like this: For many thousands of years, humans in a “state of nature” lived mainly in small, egalitarian hunting and gathering societies until, about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, they finally wised up, realized that endlessly wandering around looking for roots and berries was a miserable way to live, and decided instead to settle down, tame cattle and sheep, plant grain crops, and build cities. And then lived happily ever after—eventually with smart phones, take-out Thai, and Hulu—because of course living in cities was vastly better and everyone wanted to be there, where the action was. Inevitable, right?

One reason this story endures—and it began with Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the mid-eighteenth century—is that it implies that the kinds of social and political systems we live in now are the natural end point of thousands of years of cultural evolution, and that’s all there is to it. If small-scale, intimate, egalitarian groups—and their likewise small-scale and egalitarian governance systems–were once the norm, well, forget it—those days are gone forever. In the modern world we’re stuck with bigness and remoteness.

If that’s a dispiriting conclusion, take heart: More recent scholarship has revealed that this story is seriously misleading on several counts—and so are the conclusions that have been drawn from it.

For starters, there’s the myth that hunting and gathering was a horrible lifestyle. No doubt sometimes it was, but not so much as to justify the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes’s famous sweeping claim that early human life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Humans and our closest primate relatives are not solitary; on the contrary we are social creatures wired for small groups, and for most of our evolutionary history that’s how we lived. Also, prehistoric hunter-gatherers routinely reached old age, with as many as two-thirds surviving to their 60s or 70s (as with agricultural peoples, the biggest impediment to getting old is childhood: high infant mortality rates plagued all early peoples).[1]

As for “poor” and “nasty,” the available evidence suggests that hunting and gathering could be a pretty good way of making a living, especially compared with the drudgery of settled agriculture. As a hunter-gatherer you’re moving around from camp to camp, so the scenery changes and you’re not staring at the back end of an ox all day long. Every day is a little different. Even better, studies of past hunter-gatherers suggest that they often enjoyed a far more varied diet than their farming contemporaries, and thus better health and less chronic disease. Agriculture, after all, has been said to be a trap; as historian Ronald Wright puts it, “As we domesticated plants, the plants domesticated us. Without us, they die; without them, so do we.”[2]

Culturally, in many instances hunter-gatherers also enjoyed more leisure time, having to “work” only a few hours per day.[3] This allowed them to indulge in a generally relaxed way of life marked by socializing, conversation, music, and even high art, as revealed in the cave paintings at Chauvet and Lascaux in France, as well as many other remarkable works from paleolithic times.[4]

It’s possible, in fact, that it was the very success of hunting and gathering that led to its slow marginalization. By 10,000 years ago or so, human numbers had very gradually increased to the point that we had overspread the earth to all continents except Antarctica. Along the way, we did a lot of damage. When people arrived in North America sometime in the last 20,000 years, for instance, the continent teemed with large mammal species: several kinds of elephant, anteaters, plains camels, giant sloths, giant rodents, and others. Aggressive hunting by our ancestors, probably combined with a changing climate, drove two-thirds of those species to extinction. In Australia, Aboriginal humans probably accounted for the extinction of 86 percent of the large animals present on that continent 40,000 years ago.[5]

With human populations rising and spreading, and with the easy game increasingly hunted out and other resources overexploited, over thousands of years the pressure mounted for less extensive and more intensive ways of producing food. Ancient practices of following migratory animal herds evolved into pastoralism. The practice of revisiting places where certain useful plants grew naturally, in order to harvest them again and again, evolved into settled agriculture.

In many places, such as ancient Iraq and the U.S. Pacific Northwest, the confluence of several rich ecosystems made it possible for sizeable settled communities to continue practicing a hunting/gathering/foraging lifestyle. But in other locations settled agriculture offered a key advantage: it can produce more food, and thus support a larger population, from a smaller area of land. This didn’t happen overnight, or everywhere at the same time (and in some places it hasn’t happened at all; there are still roving pastoralists such as the Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania). As political theorist James C. Scott puts it, “[t]he shift from hunting and foraging to agriculture … was slow, halting, reversible, and sometimes incomplete.” Moreover, it “carried at least as many costs as benefits.”[6]

Among the clear costs in some cases was the rise of early states that took the form of core cities surrounded by cropland. Frequently those fields were worked by large groups of people—peasants, serfs, and/or slaves—who sat at the bottom of steep social hierarchies, often under compulsion and with little or no voice in their own governance. These pyramid-shaped societies, with masses of poor people supporting very small wealthy elites, gave rise to dictatorships, bureaucracies, ethnic cleansing and genocides, slavery, oppression of women, and other ills. All of these continue as features of modern societies as well, even nominally democratic ones. Inequality, for instance, remains rampant: In the United States in 2019, to take just one example, 88 percent of all stocks and mutual fund shares was owned by the richest 10 percent of the population. Counting all types of wealth, the richest tenth owned 70 percent.[7] Worldwide, according to the global investment bank and financial services company Credit Suisse, in mid-2019 the richest 10 percent owned 82 percent of all wealth. The top 1 percent owned 45 percent. The poorest half owned less than 1 percent.[8]

It’s crucial for an accurate grasp of our political options, however, to note that this emergence pattern was neither universal nor inevitable. Anthropologists David Graeber and David Wengrow, looking at the electrifying archaeological discoveries of the last thirty years, state categorically that “there is absolutely no evidence that top-down structures of rule are the necessary consequence of large-scale organization.”[9] They point to the ancient Mexican city of Tlaxcala as just one example: when conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived in the neighborhood in 1519, Tlaxcala was a republic governed by a council of up to 200 members drawn from both the nobility and the common people.

So, not a necessary consequence, perhaps. And as Scott points out, for a very long time states did not account for much of the total human population. They loom large in history because they basically invented history. Although systems of administrative control, like clay tokens to track resource distribution, were actually developed in small communities thousands of years before cities arose, city-states developed those into writing and then used it to glorify their rise and that of their ruling dynasties.

Nevertheless, after a slow and fitful start, states and their large, top-down governance structures have now been multiplying for several thousand years. They are ubiquitous in the modern world and more than half of us now live in cities. And in many ways it’s terrific—provided you can pick your parents and avoid being born into poverty and one of the many sprawling slums. In any case, given our numbers—now approaching 8 billion—going back to hunting and gathering on a mass scale would be impossible even if we wanted to.

But does that mean that we are stuck with our flawed top-down political systems too, that they are as inevitable as urban living seems? Urban systems have long been quite vulnerable to a variety of stresses, and remain so today.[10] Early states and even smaller settled communities were “exceptionally fragile epidemiologically, ecologically, and politically,” according to Scott. They often had to be held together by force of one kind or another, and routinely broke up into smaller units in response to political, social, climatic, and/or ecological stresses. Given the relatively greater wellbeing of people living in non-state societies, and the coercion required to keep large numbers of people plugging away at the production of grain crops year after year, it’s no surprise that states historically have had a tough time keeping up their populations. “Bondage,” Scott argues, “appears to have been a condition of the ancient state’s survival.”[11] (It still is, in many places, even nominally democratic ones. In Singapore, for instance, young men need official permission to go abroad and may even have to post bond of over $50,000 to ensure they return to complete their military service requirement.[12]) If Scott’s assessment of what’s known about early states is accurate, then smaller political and social units have at least as strong a claim to be humans’ “natural” state of governance as anything else.

Graeber and Wengrow make an even bolder argument. In their magisterial book The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity[13] (692 pages!), they lay out the case that 1) the conventional story we started this post with is indeed wildly misleading and 2) that human societies’ experimentation with social and political systems has generated a veritable “carnival parade of political forms” extending over thousands of years and of just about every conceivable size and configuration.[14] “Human beings,” they argue, “were self-consciously experimenting with different social possibilities” as far back as the Paleolithic period (which ended around 12,000 years ago).

That experimentation confounds simplistic notions about the evolution of our political arrangements. The presumed arc of development—from egalitarian bands to tribes, chiefdoms, and finally states with large cities supported by agriculture, the latter three all run by powerful elites—is so riddled with exceptions as to be incoherent. For example:

- The Egypt of the Pharaohs, the empire of the Han in China, and other large ancient states definitely depended on farming, especially of cereal grains. But farming began at least 6,000 years before those states arose, and in many places continued for millennia without such states emerging.[15] Maybe agriculture isn’t a trap after all.

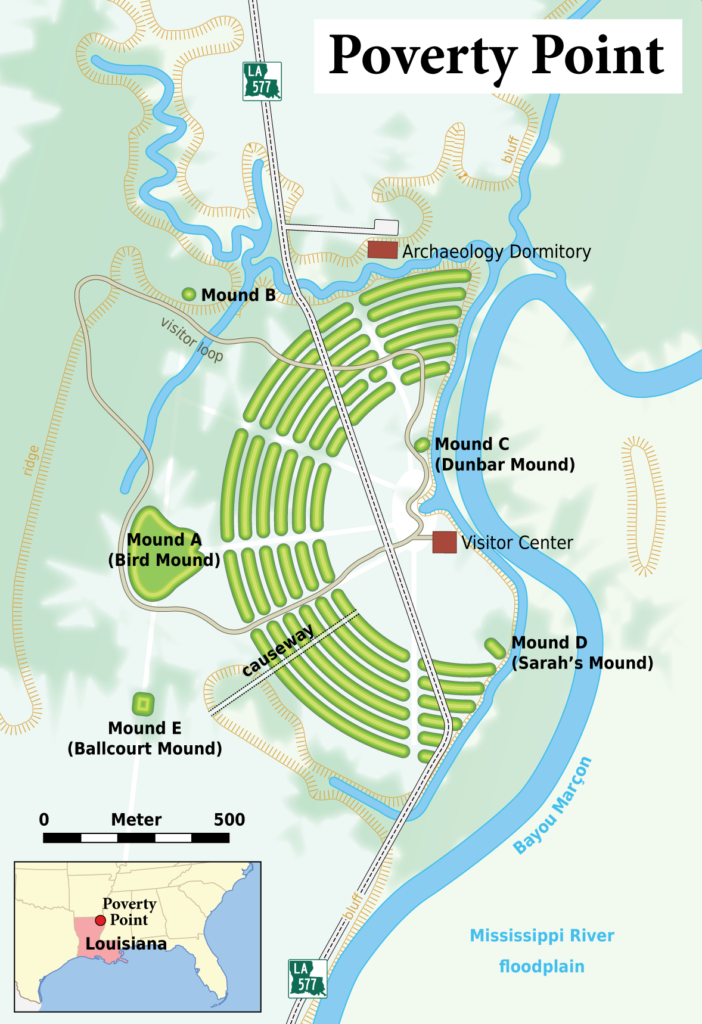

- Poverty Point in Louisiana and Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey are examples of mammoth structures built by hunting/gathering peoples who neither farmed nor kept written records. Poverty Point is over 200 hectares in extent—bigger than the fabled Middle Eastern city of Uruk—and dates to 1600 BCE. Göbekli Tepe, while not as large, dates to 9000 BCE. Neither seems to have housed many, if any, permanent residents, yet these enormous monuments, and others scattered across Europe, imply “strictly coordinated activity on a really large scale.”[16] Very large groups of people appear to have gathered periodically to perform huge collective labors and ceremonies and were likely directed by central authorities at those times—but the evidence is that the authority was temporary, even seasonal. The small bands congregating to make up large labor forces probably had few or no formal governance structures.

Poverty Point: Monumental achievement, no bureaucracy. Map of the Poverty Point archaeological site, Maximilian Dörrbecker (Chumwa) via Wikipedia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Louisiana_-_Poverty_Point_-_Karte_(English_version).png

- Cities, when they did arise, often “governed themselves for centuries without any sign of the temples and palaces that would only emerge later” (or never at all). “In many early cities there is simply no evidence of either a class of administrators or any other sort of ruling stratum.”[17]

- All over ancient Mesopotamia, popular assemblies were commonplace. “[I]t is almost impossible to find a city anywhere in the ancient Near East that did not have some equivalent to a popular assembly—or often several assemblies….”[18]

Instructive anecdotes can be found in the Americas too, like the Tlaxcalan republic mentioned earlier. Farther north, a thousand years ago the city of Cahokia (near East St. Louis) housed perhaps 15,000 people in a small kingdom marked by the kind of arrogant cruelties—mass killings for company in the afterlife—that kings seem prone to. But then rather suddenly Cahokia, and later other kingdoms in the area, just disappeared. The region was simply deserted by its inhabitants. Their descendants “reorganized themselves into into polis-sized tribal republics, in careful ecological balance with their natural environment.”[19]

Talk about experimentation! In walking away from monarchy, the ex-Cahokians set the standard for what Americans and Europeans are so proud of doing several hundred years later.

So where does all this leave us?

You could see it as a muddle—but only if you’re desperate to find a straight and rising political line from the ancient past to the modern world. Obviously there isn’t one. The record shows that humans have tried nearly every conceivable governance arrangement at one time or another, most of them repeatedly. We haven’t defaulted to a particular system—to the contrary, we are “projects of collective self-creation.”[20]

If no particular system of governance is inevitable, what looks like a muddle is actually a rich suite of options. The problem remains the same as ever: “The ultimate question of human history … is … our equal capacity to contribute to decisions about how to live together.” We are free to adopt the form of governance that works for the time and place we live in and gets us closer to where we want to be. This has happened countless times in human history, when people have seized the possibility, as David Graeber puts it, of “a conscious rejection of certain forms of overarching political power which also causes people to rethink and reorganize the way they deal with one another on an everyday basis.”[21]

We believe that a deep form of democracy based on citizen deliberation is the best form of governance for human beings and that this is a good time to start building it, regardless of what the future brings. How to do that, and how to scale deliberation so it can be effective in large as well as small polities, will be explored in upcoming posts.

Endnotes:

[1] Jason Godesky, “Hunter-gatherers enjoy long, healthy lives,” Rewild.com, http://www.rewild.com/in-depth/longevity.html, May 2, 2016.

[2] Ronald Wright, A Short History of Progress (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2005), p. 47.

[3] See John Gowdy, ed., Limited Wants, Unlimited Means: A Reader on Hunter-Gatherer Economics and the Environment (Washington, DC: Island Press, 1998).

[4] For a vividly imagined and plausible portrait of paleolithic life, see Shaman, by Kim Stanley Robinson (New York: Orbit, 2013).

[5] See Clive Ponting, A Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations (New York: Penguin Books, 1991). Combined effects of hunting and climate change in Tatiana Schlossberg, “12,000 Years Ago, Humans and Climate Change Made a Deadly Team, New York Times, June 17, 2016, retrieved March 15, 2020 at https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/18/science/patagonia-extinctions-global-warming.html.

[6] James C. Scott, Against the Grain (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017), p. 10.

[7] U.S. Federal Reserve, “Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989, https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/dataviz/dfa/distribute/chart/#quarter:121;series:Net%20worth;demographic:networth;population:1,3,5,7;units:shares, viewed June 10, 2020.

[8] Credit Suisse, Global Weath Report 2019, p. 2.

[9] David Graeber and David Wengrow, “How to change the course of human history (at least, the part that’s already happened)”, Eurozine, March 2, 2018; https://www.eurozine.com/change-course-human-history/.

[10] To keep New York fed, for instance, requires more than 13,000 truckloads of food delivered and processed every day; see A Stronger, More Resilient New York, published by the City of New York in June 2013: https://toolkit.climate.gov/reports/stronger-more-resilient-new-york.

[11] Scott, op. cit., pp. 27 and 30.

[12] Austin Ramzy, “Singapore Says ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ Author Skipped Military Service,” New York Times, August 22, 2018; https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/22/world/asia/kevin-kwan-crazy-rich-asians-singapore-military.html?rref=collection%2Fsectioncollection%2Fbooks&action=click&contentCollection=books®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=sectionfront.

[13] David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).

[14] Ibid., p. 4.

[15] Ibid., pp. 127-8.

[16] Ibid., p. 89.

[17] Ibid., p. 277.

[18] Ibid., p. 301.

[19] Ibid., p. 452.

[20] Ibid., p. 9.

[21] David Graeber, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2004), p. 56.

Teaser photo credit: Göbekli Tepe, Şanlıurfa, Author Teomancimi, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:G%C3%B6bekli_Tepe,_Urfa.jpg