I keep writing prefatory posts before wading into the content from Parts III and IV of my book A Small Farm Future in this blog cycle, for which apologies. I promise this will be the last before I get down to business, although I do believe a little business is transacted below. Anyway, this means I’m going to hold off further discussion of Max Ajl’s important book left over from my last post for the time being.

In this post I want to talk about another writer, and relate his work to the question of a small farm future. The man in question is Marshall Sahlins, among the most distinguished of anthropologists from the latter part of the 20th century, who I only recently realized had died earlier this year.

There’s a small personal backstory to this. Many years ago, Sahlins offered me the opportunity to do a doctorate with him at the University of Chicago. A callow undergraduate, I was almost quaking as I entered his office during my visit to that august institution, like a member of some low-ranking lineage making offerings at the holy shrine of a fearsome ancestor. I guess David Graeber would have been among my cohort had I gone there, just a few years ahead of me, though of course I had no idea at the time who he was. But something about Chicago’s serried streets, the palpable misery of the graduate students and the tribal warfare within the anthropology department put me off. Or maybe it was more my own imposter syndrome at the thought of dwelling among such gods. In any case, Sahlins kindly wrote to me after I’d spurned his offer, wishing me “good luck and good anthropology”.

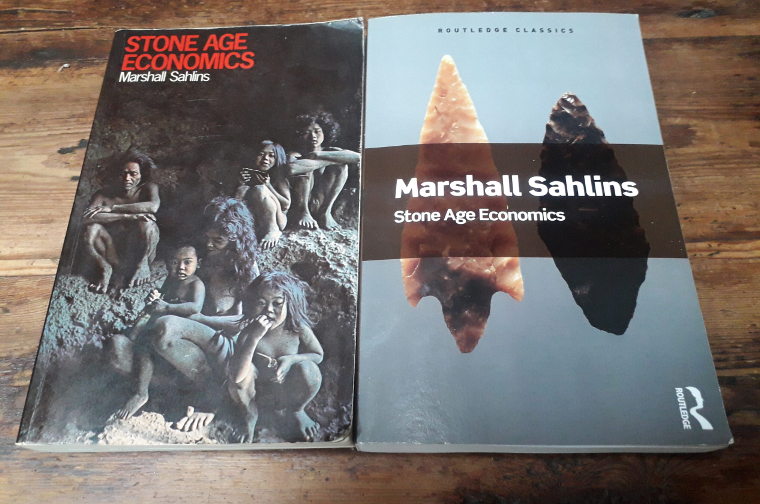

Well, I feel I’ve had a lot of good luck in my life so far. As to the anthropology, I want to mention Sahlins’s classic book Stone Age Economics, first published in 1972. This has been a touchstone work for me, and every few years I’ve re-read most of it. I went back to it again some weeks ago, but too many pages in my old copy were falling out, and the rest were so laden with penciled annotations from years of reading and re-reading that there was no space to scribe my latest thoughts. So I bought a new copy. The 2017 Routledge edition comes with an introduction from David Graeber, and a cover photo of two elegant stone-age blades – a marked contrast to the original edition’s picture of a dusty and sombre-looking group from the dubiously provenanced Tasaday people, squatting rather miserably in a cave.

Symbolically, the photos represent changing views of ‘primitive’, ‘indigenous’ or foraging peoples that this very book played no small part in effecting. By far the most famous essay in its pages – one of the best-known of all anthropology essays outside the discipline itself – is the first one, ‘The Original Affluent Society’, in which Sahlins goes to some lengths to show that far from living lives of endless misery and toil, as modernist ideologies often proclaim, foraging societies were lightly encumbered with labour compared to large-scale agricultural societies, with plenty of time for leisure and good living.

This argument is such a commonplace today that inevitably the pendulum has started to swing the other way, and various critiques of Sahlins’s thesis have appeared. Whatever. For me, the next three essays in the book, two concerning what Sahlins calls the ‘domestic mode of production’ and then his spellbinding essay on ‘The Spirit of the Gift’, are much the most important ones in the collection. I’ll talk about the gift essay in another post. Here I’ll restrict myself to some remarks about his two essays on the domestic mode of production.

As I (re-)read these essays recently, I was shocked to notice how unconsciously indebted I was to them for some of my arguments in A Small Farm Future. Strange, considering how often I’d read them. Perhaps they’d become so familiar I’d unthinkingly adopted them as my own. Ironically, it seems that the ‘good anthropology’ Sahlins wished for me all those years ago may have manifested largely in me reinscribing for contemporary political purposes some of his own insights about societies supposedly left behind by modernity. I only hope my act of ancestor worship has some modern efficacy.

And so: the domestic mode of production. ‘Mode of production’ is a concept especially associated with Marxist thought, and in his foreword David Graeber says that these essays were “the closest Sahlins ever came to an experiment with Marxist models” (p.xiv). In truth, he didn’t come that close. Which suits me fine – as I see it, Marx is another ancestor who deserve some honour, but no cultish devotion. And on that point, just to say that the only person who responded to my question last time as to whether I should engage with Alex Heffron’s and Kai Heron’s highly charged Marxist attack on my book was one K. Heron, who, to paraphrase, thought not. Yet some of their points in that review are a useful foil to arguments I wish to make, so I will refer to them in passing nonetheless in this and future posts.

Sahlins’s argument about the domestic mode of production is that in so-called ‘primitive’ societies there is a deep structural orientation to production for the needs of the household, which is usually a small unit of closely related kin. Neither ‘the economy’ nor ‘work’ are alienated from the daily practice of household members: the ‘economic’ is a “modality of the intimate” and the disposition and allocation of labour are “in the main domestic decisions…taken primarily with a view toward domestic contentment” (p.69). The household is oriented to meeting its own socially defined needs. There is no inherent tendency to the amplification of production or the accumulation of wealth. It’s precisely these features of household production, together with the immediate feedback the household gets about the ecological consequences of its self-provisioning, that to my mind make it a plausible vehicle for renewable future societies.

I discuss this idea at various points in my book, including on page 267 where I frame it within a populist imaginary of “the ideal citizen…[spending] a good part of their day striving for flourishing and livelihood. The next day, they do the same again, probably in the same way. There’s no higher political purpose”.

Heffron and Heron singled out this passage for some scorn, albeit by hedging it with all sorts of accusations of patriarchy, monotony, debt and market dependence which are not intrinsic to it. But I will take my stand on it. Better a domestic mode of production than Stakhanovite self-exploitation, statist expropriation or implausible, future-obsessed utopias of collective overcoming.

Nevertheless, Sahlins himself speaks rather dimly of this domestic mode – its orientation to mere self-satiation threatening dangerous undershoot, its orientation to itself threatening dangerous social conflict. He makes the point that while households in the domestic mode of production do cooperate with each other, this does not “institute a sui generis production structure with its own finality, different from and greater than the livelihood of the several domestic groups” (p.70) – a point I will return to when I come to discuss commons. For him, in order for the domestic mode of production to become a plausibly functional society, some such ‘greater than’ production structure is needed, and in his view it’s often provided in ‘primitive’ societies by hierarchical kinship structures such as chiefdoms that ramify beyond the individual household and coax additional productivity from them. But chiefdoms are not kingdoms. They have not “broken structurally with the people at large” (p.133). Chiefs remain kinsfolk and are structurally limited by that fact, such that chieftaincies are inherently unstable and prone to crumbling back into their constituent household elements.

In this view, then, chiefdoms don’t arise as it were ‘naturally’ when household production achieves a surplus. They’re inherent to the domestic mode, oriented to creating a surplus out of household production, and represent a tension or a contradiction within the domestic mode of production. Perhaps this is the ‘Marxist’ element to Sahlins’s analysis, since the idea of contradictions powering society is a leitmotif of Marxist analysis. Yet whereas in Marxism the resolution of contradictions drives a society progressively ‘forward’ in history towards improved forms and ultimately to a perfected communism, in Sahlins’s domestic mode of production the contradictions remain static and inherent, a flaw in the jewel of progressive society or, in Sahlins’s words, “a threshold which…was the boundary of primitive society itself” (p.133).

Sahlins did more than most during his career to break down the evolutionary sequence seemingly hard-wired into modernist thought of a historical trajectory from ‘primitive’ society (the very word redolent of an outmoded evolutionism) to ‘feudal’ society and thence to capitalism and (in Marxist thought) ultimately communism. Here, however, I think he somewhat succumbs to it.

I have to assume that Heffron and Heron are still labouring with this discredited evolutionism when they characterize my arguments as ‘feudal’ advocacy for parasitic landlordism, since they cast around for evidence of it in my writing, fail to find any, and then simply assert it on the basis of a meagre harvest from my words. Indeed, the popular notion that any localized, small farm society must somehow be redolent of a bygone ‘feudalism’ remains strong. Yet what generates feudalism is not farming scale or style, nor even economic relations of landlord and tenant (which I strongly oppose throughout A Small Farm Future), but political relations. In future posts I’ll be looking at this politics and explaining why a small farm future might well be neither capitalist, communist, feudal nor necessarily ‘primitive’. There can be other ways of households generating surpluses.

Despite the dubious evolutionary element to his argument, Sahlins himself partially breaks with it throughout Stone Age Economics (and much more so in later writings), as for example when he likens certain kinds of peasant economy to the domestic mode of production of ‘primitive’ economies: “a fragmented peasant economy may more clearly than any primitive community present on the empirical level certain profound tendencies of the DMP…” (p.80)

This argument was strongly influenced by Alexander Chayanov’s populist economic analyses of pre-communist Russian peasantries that had only recently been translated into English at the time of Stone Age Economics. Chayanov, I’ll note in passing, was murdered by Russia’s communist regime in 1937 for thinking wrong thoughts about the peasantry. Luckily, such a fate has not yet befallen me in speaking up for the potentialities of semi-autonomous household production, but Chayanov’s killing is a salutary reminder that the stakes in these discussions can be high. Only a few decades after his death, Russia’s communist regime collapsed, creating a power vacuum filled by a mafia capitalism that many ordinary Russians survived precisely by turning to Chayanovian household production of use values. There are wider lessons here, I think, about how the domestic mode of production might intercede within a ravaged state apparatus in societies of the future.

In Stone Age Economics Sahlins explicitly excluded from his purview this world of modern centralized states supposedly standing on the other side of his threshold of ‘primitive’ societies. Later on, in an essay co-authored with David Graeber, he recanted this stark distinction:

In retrospect, we may well discover that “the state” that consumed so much of our attention never existed at all, or was, at best, a fortuitous confluence of elements of entirely heterogeneous origins (sovereignty, administration, a competitive political field, etc.) that came together in certain times and places, but that, nowadays, are very much in the process of once again drifting apart

DAVID GRAEBER AND MARSHALL SAHLINS. 2017. ON KINGS. HAU BOOKS. P.22

I agree with this diagnosis. I argue in A Small Farm Future that many of the elements of ‘the state’ that have typified the modern world are, for various reasons, in the process of disintegrating, and for many of us or for our descendants the outcome is likely to be a relatively autonomous world of local household production akin to Sahlins’s domestic mode – which, at its best, may not be such a bad outcome.

Not such a bad outcome, but not in any sense a perfect one. While I think Sahlins somewhat over-eggs the difficulties and contradictions of the domestic mode of production, I believe he does it advisedly to point to the inherent tensions and difficulties that human societies of all kinds experience in constituting themselves, and his analysis therefore works as a counterweight to airily romanticized progressive ideologies such as the ‘collective class struggle’ that Heffron and Heron invoke as, dare one say it, a deus ex machina for overcoming structural difficulties. And Sahlins does it with a gruff admiration for the practical workarounds that people involved in household production worldwide have found historically to these intrinsic difficulties. Whereas the earlier Marx – and Heffron and Heron after him – scorned the political potential of household or peasant societies for their inability to come together collectively, employing the famous metaphor of potatoes in a sack, I offer A Small Farm Future at several levels as an argument that champions those potatoes, botanically and metaphorically, each and every one of them a marvellous but ultimately flawed attempt to solve certain intractable questions of how to exist as one part of something bigger.

Sahlins’s writing wasn’t especially easy for those not steeped in social science, but it had a kind of muscular workaday honesty, sprinkled with wry humour, which always returned to the practicalities of how people in actual historical societies have gone about their business, rather than involving itself in theoretical speculations or projections of idealized futures. A wise course. But, as I argue in A Small Farm Future, the burden of present generations is now to project new futures urgently in the face of the unravelling of the present mode of production, however difficult the task.

In doing so, I see myself as working within the traditions of left-wing (but not Marxist) politics. I don’t particularly want to be a renegade, although I’m less closed-minded than I once was to the possibility that other political traditions might have something of value to say. Indeed, these days I find much leftist writing, including that of a certain review of my book, to be so self-satisfied with its unexamined prejudices – positive and negative – around such things as collective class struggle, the forms of property, the nature of hierarchy or the forms of kinship, that a bit of reneging seems necessary. I don’t suppose my efforts will bear much fruit, but so be it. It’s a long-haul thing.

Talking of long hauls, with hindsight perhaps I didn’t specify clearly enough in A Small Farm Future the different time registers involved in thinking about post-capitalist ecological futures. Joe Clarkson said recently on this site that he was more interested in immediate issues of social transformation because, longer-term, people will figure out their small farm futures somehow – the challenge is the path from now to there. It’s a strong point, and in my book I do make some attempt to address it (more on that in future posts), but in truth I think the immediate transformation is going to involve a thousand kinds of craziness that can’t easily be predicted or allayed, so my focus in the book was to characterize in outline some of the main issues that emerging small farm societies in the interstices of this craziness would have to wrestle with – without attempting any kind of complete blueprint for how they should or would organize themselves. Inevitably, one has to make assumptions about the kind of future world and the kind of future societies one is projecting, and this is always open to challenge. I could probably have signposted this a little better in the book. But overall I stand by that project.

For their part, Heffron and Heron wrote “As Marxists we believe that we must look for the contours of an eco-communist future in struggles against the capitalist present.” So the difference with my project is clear. As me, I’m not especially interested in looking for the contours of an eco-communist future. There are a few aspects of ‘eco-communism’ I might endorse, but I’m doubtful many current struggles against the capitalist present – and certainly few that are framed through Marxist optics – will be especially generative of post-capitalist ecological societies long-term.

Heron is scornful of ‘disaster’ politics and its presentiments of sudden transformative shocks to present social systems. This seems a necessary stance for him to take, because struggles against the capitalist present can only build a worthy long-term politics within capitalism’s own persisting ambit – and this, I think, constitutes a ‘threshold’ of capitalist ideology that Marxism itself cannot cross. This was a theme in Culture and Practical Reason (1976), Sahlins’s next big book after Stone Age Economics, where he provided a sustained anthropological critique of what he saw as the limited bourgeois economism of Marxism (Baudrillard’s The Mirror of Production did something similar around the same time). I think this bourgeois economism is apparent in Heffron and Heron’s scorn for peasantries, kin structuring, household production and household use values, and their enthusiasm for ill-defined large-scale collectivisms and state formations.

From Sahlins, I’ll take my stand on the possible, but by no means paradisiacal, domestic mode of production of the future, and on the unlikelihood of generating long-term culture out of short-term conflicts of material interest. I’ll try to fill out the implications of this in future posts, where I hope I can better ground the rather abstract arguments I’ve made here.