Lately, it seems like everyone is talking about ‘30×30’. The US president, Joe Biden, recently committed the country to protecting 30% of its lands and waters by 2030. At the next meeting of the Convention on Biological Diversity, world leaders are widely expected to embrace a global 30×30 target for conservation. These moves are in line with a larger community of scientists who have been calling for 30% of the earth’s lands and waters to be protected by 2030, and 50% by 2050, in order to mitigate the worst effects of climate change.

At first glance, 30×30 seems like a winning proposition. Protected areas, such as national parks and nature reserves, currently hold about 12% of global land-carbon stocks (at present, about 15% of global land area and 7% of global marine area is protected). Protected areas act as refuges for biodiversity, protecting many of the planet’s most endangered species. Conserved lands also provide a number of other important socioecological benefits, from flood mitigation to heat reduction to cultural meaning.

What the millions of annual visitors to protected areas may not realize, however, is that conservation has come at a cost. Conserved lands are often presented as untouched wildernesses – places unsullied by human occupation and influence. In almost every case, this is a profound mischaracterization. Most of the places we now call national parks, game reserves, and national monuments were once occupied and managed by humans (sometimes until very recently). As historian Mark Spence put it over two decades ago, an untouched wilderness needed to be created before it could be protected. That is, millions of people have been dispossessed in the name of conservation. 30×30 threatens to dispossess many more.

Conservation via dispossession – the eviction of human inhabitants in order to create a protected area – was first documented in the Caribbean under British imperialism but was perfected by settler colonists in the United States. All of the protected lands in the US are stolen lands. The conservationist project took off in the US after the Civil War, offering a point of pride and connection to an otherwise divided nation. America’s famed national parks, such as the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, and Yosemite, were created through the eviction of Indigenous inhabitants. The establishment of national parks in the US was often contemporaneous with the enclosure of Indigenous peoples onto reservations. Dispossession is not limited to the 19th and 20th centuries. Indigenous communities are still working to restore their access to, and authority over, the US’s protected lands.

The model of conservation via dispossession was exported from the US around the world and remains in practice today. Most of those who have been evicted in the name of conservation are Indigenous. It is no wonder, then, that Indigenous advocacy groups, such as Survival International, oppose the global plan for 30×30. Doubling the extent of global protected areas threatens to displace many more communities. The prospect of widespread displacement for conservation is not only a humanitarian outrage, but also an ecological affront.

Many of the communities that are displaced by protected areas have lived sustainably on the land for generations. About half of the land chosen for conservation is managed by Indigenous peoples; in the Americas, that figure is as high as 80%. Conservationists typically seek to protect lands that maintain a high degree of biodiversity, sequester carbon, and/or support unique ecosystems. The fact that conservationists choose Indigenous peoples’ lands for protection evidences the high conservation value and good condition of Indigenous-managed lands (in addition to a racist political-economic order that makes Indigenous lands ‘available’). Globally, the UN recognizes that Indigenous peoples protect 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. Scientists have shown that Indigenous management provides the same level of ecosystem support and protection as any imposed protected area. Conservation via dispossession removes the very people who take care of our most important ecosystems.

Eviction has been shown to lead to a cascade of deleterious environmental impacts. In 1882, California state commissioner M.C. Briggs observed that the lack of traditional Indigenous fire management in the Yosemite Valley following the eviction of the Ahwahneechee had led to an influx of new young tree growth. Briggs remarked, “While the Indians held possession, the annual fires kept the whole floor of the valley free from underbrush, leaving only the majestic oaks and pines to adorn the most beautiful of parks. In this one respect, protection has worked destruction.” What Briggs observed was far from an isolated phenomenon. Although conserved lands are depicted as empty and pristine, they are in fact intensively managed landscapes. Accordingly, the loss of human managers with generations-long relationships to the land is all but guaranteed to change the ecosystem.

Furthermore, displacement tends to force communities into the lowest rungs of the market economy, where there are significant incentives for poor, landless people to deforest, poach, and otherwise depredate the environment. Eviction disrupts established relationships between communities and the land, including systems to regulate harvesting, sometimes leading to anti-environmental outcomes.

More troublingly, conservation may facilitate elite access to resources. Historically, conservation was used as a tool to enhance elite wealth by securing reliable access to natural resources, such as timber, and creating new leisure and tourism ventures. Today, elites continue to profit from eco-tourism, bioprospecting, trophy hunting, and outright resource extraction within the boundaries of protected areas.

We cannot rely on conservation to lead us into an environmentally or socially just future. Instead, we must consider how else to protect all life on earth. Indigenous communities already have the solutions to our most urgent socioecological crises.

Globally, about 370 million people identify as Indigenous. Indigenous peoples are not a monolith and it is neither possible nor desirable to make sweeping generalizations about so many diverse cultures. Yet, what binds Indigenous peoples together, according to Indigenous scholars Taiaiake Alfred and Jeff Corntassel, is “the struggle to survive as distinct peoples on foundations constituted in their unique heritages, attachments to their homelands, and natural ways of life… as well as the fact that their existence is in large part lived as determined acts of survival against colonizing states’ efforts to eradicate them culturally, politically and physically”. There is also ample evidence to support the ecological importance of Indigenous ways of life, as stated earlier.

Indigenous peoples are not inherently connected to the land; racist stereotypes like the ‘noble savage’ and the ‘ecological Indian’ obscure the sophisticated socioecological and political-economic systems that contribute to Indigenous stewardship. Indigenous movements for decolonization and resurgent Indigenous governance seek to restore Indigenous socioecological relations over all colonized lands.

On Turtle Island, otherwise known as North America, Indigenous women, trans, queer, and Two-Spirit folks are at the forefront of decolonization movements. The settler-colonial projects in the US and Canada exposed the environment and Indigenous womxn to unique forms of violence. In many communities, the imposition of capitalist heteropatriarchy denied Indigenous womxn and queer folks their traditional positions of authority and disrupted gendered relations to the land. The ongoing erasure of Indigenous land and life can be seen most clearly at extractive sites, such as Line 3 and Standing Rock, where violence against the land feeds violence against Indigenous womxn. Most recently, Line 3 pipeline workers were implicated in a sex trafficking ring that targeted Native women.

Indigenous calls for land and water back in the US and Canada are neither abstract nor metaphorical; they are material and urgent. The Red Nation, an Indigenous resistance organization based on Turtle Island, maintains that: “The stakes are clear: it’s decolonization or extinction.”

The Red Nation’s call to action is hardly an isolated one; it reflects the philosophy of Indigenous movements throughout Turtle Island. These recognize that the survival of humans and our more-than-human relatives depends on a shift to a dramatically different mode of socioecological organization.

Importantly, decolonization is about more than just the return of stolen lands and waters (though this is a crucial aspect). The return of stolen lands must be accompanied by shifts in our systems of production and reproduction, including the abolition of capitalism, patriarchy, neocolonialism, Western notions of development, and other forms of social domination. Some Indigenous feminists use the term ‘rematriation’, which is a “call for moral and political commitment by Indigenous leadership and others to restructure Indigenous governance structures in a way that reinstates the centrality of women”.

Over the past year, I have been privileged to meet some of the Indigenous people leading resistance movements in the south-western US. Their struggles against fracking, uranium mining, nuclear waste storage, and copper mining, to give just a few examples, highlight the inseparability of Indigenous emancipation and environmental protection. They are not just resisting a single extractive project, but rather fighting for an entirely different future. Their work shows that the land will not be free until Indigenous peoples are free, and Indigenous peoples will not be free until the land is free.

Conservation is incapable of delivering long-term environmental protection because it leaves in place the systemic drivers of environmental degradation: capitalism, (neo)colonialism, patriarchy, Western notions of development, and social domination. Evicting nature’s caretakers in the name of conservation will increase human suffering and decrease environmental protection. To ensure a healthy, just future for all life on earth, we must embrace decolonization as our guiding environmental policy.

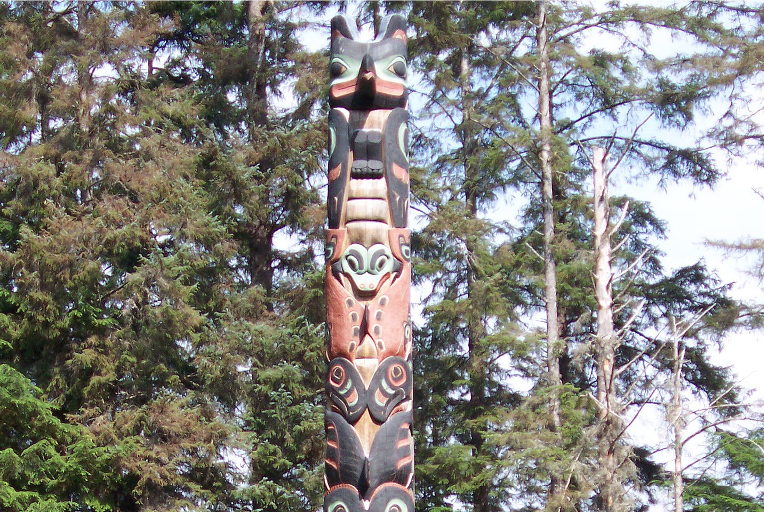

Teaser photo credit: By The original uploader was Lordkinbote at English Wikipedia. – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by SchuminWeb using CommonsHelper., CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17056802