No, life has not yet been found on Mars, but imagine waking up to that headline. How would you react? The headline’s font would be huge on print newspapers—maybe one word per page, occupying the first four pages. Some bold papers might even put one letter per page and go so far as to have blank pages for the spaces. The point is, it would be big news.

So I ask again, what would this stir for you?

For me, the swirl would be thick with competing thoughts and feelings, tripping over themselves to get out. First would be the raft of questions stemming from pure curiosity. Is it DNA-based? Is it a separate start, or do we share some ancient microbial ancestor—possibly shuttled from one body to the other following a meteoric impact? What lessons can we learn about how life forms? Can we get the discovered lifeforms to call us Mama or Dada? Will they make good pets?

One can imagine the discovery team, whether at NASA or elsewhere, ecstatic with joy. The entire exploration establishment around the planet would likely be giddy. SETI folks would probably be unable to chew for a while, wearing fixed grins.

I would share many of these same reactions, for the pure joy of discovery and the novel opportunity to re-examine what it means to be a part of life on Earth. But then it dawns on me just how devastating the news might actually be for the human race.

I’ll start with the simple and obvious statement that the universe does not appear to be abuzz with civilization. As far as we can tell, galaxies look all-natural (boring). No intergalactic Las Vegas pops up. Within our own galaxy, all the peering and snooping in the world has not shown one scrap of credible evidence for a technological civilization. I fully understand how hard the job is, and that not having found evidence yet is inconclusive on the matter. But let’s call it disappointing, and disconcerting. At least we can say that the galaxy is not teeming with technological life in a web of vibrant interstellar commerce, complete with jackass adolescents playing pranks on us primates.

In the context of the Drake Equation, which is essentially the product of many probabilities geared to estimate the number of civilizations we could expect to hear from, the empirical answer samples to zero. This forces calculated outcomes of the Drake equation to be small—not terribly far from zero.

As time goes on, we have systematically increased the values of many of the individual probability factors: we know that planetary formation is ubiquitous around other stars. We know that rocky planets are common. Many lie in the habitable zone where water can be in liquid form. Meanwhile, the probability of detecting alien life only improves with technology and search time. So while all these factors have increased, the Drake product remains empirically and stubbornly small, meaning that the other unknown factors are forced to diminish. The probability of life forming, the probability of technological development of a species, and the duration of technological civilizations are collectively squashed with each new advance on the other fronts.

Now we imagine the earth-shattering news that Mars has life. Suddenly, one of those factors gets an enormous boost. This is especially true if the new lifeform represents an independent spontaneous start, not seeded from Earth or Earth’s life seeded from that on Mars. Even if sharing ancestry, the idea that life can get around and survive in wildly different environments after a traverse of space surely pumps up the probability of life thriving elsewhere.

But Drake still rounds to zero, in practice. So what factor takes the counterbalancing hit?

The reason the news would ultimately depress the hell out of me is that it would seem to put the chances of human civilization surviving for many millennia radically smaller than it might have been before hearing the news. If life is so common that the very next planet has it also, then it’s presumably everywhere in the galaxy. A huge unknown would have been lifted, and the associated probability for life soars. The remaining pieces suggest that technological life is either rare, short-lived, or both.

It’s harder to believe that technological development would be rare, once life takes hold. Around stable stars in stable orbits, evolution will promote various advantages, intelligence being one of them. The spark of life on Earth is the head-scratcher for us, not the more obvious trajectory of intelligence—which can be seen in lines as diverse from ourselves as dolphins, ravens/parrots and octopuses.

That leaves me with the sinking sense that finding life on Mars would be a devastating blow to our chances for a long technological run.

I’m not saying it would be the last nail in the coffin—just that our prospects dim noticeably. So while others dance in the streets, and I myself eagerly await more understanding of the new life form, I’ll take it pretty hard, on the whole. Surrounded by celebration, I picture myself as a surly loner—best avoided and ignored—baffling the partiers by demanding to know “what are you grinning about?”

P.S. This was a bit of a detour to the main thread recently, evaluating the big-picture perspective of our long term prospects and evolutionary insights. It does tie in to a section of the new textbook on the Fermi Paradox. But in the next post, I will resume this existential exploration, asking the core question: to what end?

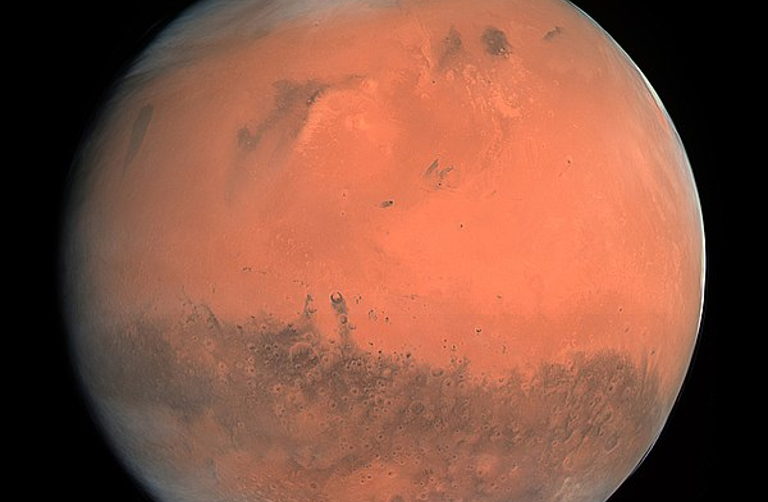

Teaser photo credit: ESA & MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/RSSD/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA