Discussions of the threat to liberal democracy have neglected perhaps the most surprising source that is one of the major arcs of history of the last three decades: globalization. It promised the promotion of liberal democracy encapsulated in neoliberal economics whose components include free movement of capital and finance, free trade, free movement of people, and the free transfer of ideas through social media. While globalization has achieved many of these four freedoms, it has also fostered its precise opposite: a borderless world that has stripped the principal source of political democracy – the nation state — of much of its political and economic legitimacy for the liberal democracy that created globalization. Governments became weakened by the very fraying of its borders wrought by a globalization they promoted.

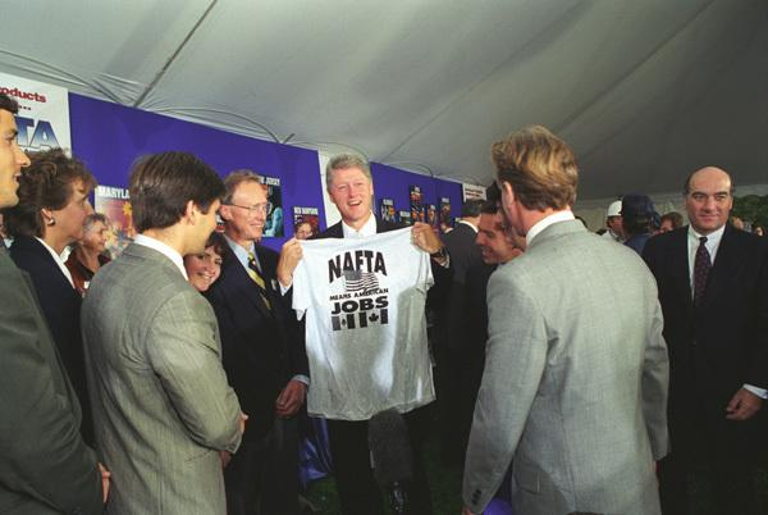

President William J. Clinton participating in a NAFTA products event on the South Lawn of the White House. President Clinton holds up a t-shirt that says “NAFTA Means American Jobs.” / Photo credit The U.S. National Archives/Barbara Kinney/Public domain

President William J. Clinton participating in a NAFTA products event on the South Lawn of the White House. President Clinton holds up a t-shirt that says “NAFTA Means American Jobs.” / Photo credit The U.S. National Archives/Barbara Kinney/Public domain

Many citizens lost protection from the juggernaut of globalization whose project fostered the denuding of political constraints on its borderless operations. They became the constituency for an authoritarian challenge to globalization and the political parties that had created it. Historical determinism was globalization’s persuading premise along with a technological transformation that reinforced the idea that globalization was inevitable, inexorable, and not regulatable. It had its public intellectual promoters both on the political right and center-left. TINA – there is no alternative to this historical and technological imperative, they proclaimed. The Spirit of Davos’s annual recitation of these talking points reinforced the consensus that became ideological certainty. Its few challengers were quickly dismissed as Luddite outliers who did not understand the wonders of globalization.

In 1986 I wrote in my book, The Money Mandarins, about the incipient rise of tribalism as a response to the incubation, at that time, of globalization. “Loss of national control shows up in a re-emergence of political and economic nationalism as compensation for the decline in the government’s legitimate responsibility in economic affairs,” I wrote. The British political economist, John Weeks, has analyzed the perils of a neoliberal, de-regulated globalization which he labels, “decommissioning democracy,” with the inherent threat from the rise of authoritarianism. All this is at odds with Milton Friedman’s most publicly influential book, that he titled Capitalism and Freedom, in order to show the connection between these two grand ideas that extended Friedrich von Hayek’s analysis in The Road to Serfdom.

Where and how did the claims of expanded “freedoms” from globalization go wrong? At its core globalization is at tension with national political democracies almost by definition. If globalization’s beauty is its ability to transcend national boundaries, doesn’t it also supersede democratic political systems within nations that were established to represent its voting citizens? Citizenship and the right to vote is crucial to understanding this. There is no such thing as a global citizen with any legal standing, notwithstanding its frequently proclaimed existence by utopian promotors of the global system. Citizenship is only granted by nations with reciprocal rights and responsibilities between a citizen and the granting authority: government.

We have always had an international economy – trade in products and services, movement of people, international companies. For many analysts and popular renditions, these metrics are the essence of globalization, except on steroids. Globalization’s political-economic reach is different, however. A principal difference, which I wrote about in 1986, is “private commercial and banking interests [operating] supranationally beyond the public policy and regulatory reach of national governments.” These operators then leverage their power to influence policy changes within nation states to enable their global project to move forward. Their “industrial policy” aims to produce products and offer services in low-labor-cost countries with minimal regulatory structures – whether for the environment, worker protections, or any other. The well-known consequences are shuttered factories, towns vacant of jobs and sprit, and an affected populace ripe for mobilization against these global elites and their political enablers.

Along the way corporate and financial tax collections became eroded by the ability of global enterprises to use a device called, transfer pricing, by which costs are manipulated to show low profits in high tax countries and higher profits in low taxed countries. A 2016 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that between 2006 and 2012, what they label “large” corporations, paid an average effective corporate profit tax rate of 14% when the statutory rate was 35%. General Electric, whose CEO Jeffrey R. Immelt chaired President Obama’s business council on job creation, paid an average of 5.2% on total profits of $114 billion over the 15-year period from 2001 to 2015, based on their annual reports. To add further insult to the public treasury, the company received credit offsets against future taxes of $5 billion. With reduced revenue, governments have less for the public good. People are left to pay a larger share for government. They are easy prey for complaints about high taxes, poor services, and unresponsive bureaucracies – persistent positions of the political right.

What emerges is a race to the bottom as wealthier countries with more robust democratic institutions are reduced to the common denominator of less-democratic countries. Not only is there offshoring of production and service-provision. There is also trade in public policies. The U.S. exports neoliberalism and imports reduced regulatory structures and weaker tax collections in order to compete in this borderless universe. What travels on the backs of quantitative increases in trade, investments, and global finance is the import and export of ideology, lower wages, and regulatory weakness.

The public atrophies, governments are weakened and discredited, and those left out of and behind in this global system become ignored or neglected. Hillary Clinton’s “deplorables” was an unfortunate, but all too candid, description of those ignored constituencies. This is a perfect recipe for a right-wing populist response to globalization’s unintended consequences.

Globalization’s champions and public designers arose from the moderate liberal left – Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, enhanced by Barak Obama – not from the center right that was happy to go along with something they could not have realized themselves. Coming from the moderate left it was made possible and palatable.

Why would someone with President Bill Clinton’s political leanings become the steward for a globalization whose consequences appear antithetical to his moderate progressive and southern populist instincts? Without his telling of the story one can only speculate. There probably is no one meeting or set of decisions that morphed into a coherent set of transforming structures. Things just don’t usually happen that way in public policy. It is more like specific steps that end up finding some later coherence to make a story out of them. It started with his dogmatic acceptance of a very specific and peculiar version of “free trade” that defined him as a “New Democrat,” separating himself from New Deal Democrats.

Clinton saw an opportunity early in his years in office to take on trade issues that had floundered during George H. W. Bush’s presidency to the point they had been abandoned. He knew he would have overwhelming Republican support so he could see victory to offset his health care legislative problems. NAFTA – the North American Free Trade Agreement (1994) — became the initial thrust and, once that overcame enough traditional Democratic progressive opposition to pass it, he proceeded to the revolutionizing concept of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO’s (1995) mandate authorized it to rule juridically against policies inside nation states that interfered with their mission to promote this peculiar and ahistorical version of “free trade.” They were given significant enforcement powers. It truly is the first global governance agreement with powers to override national law and penalize governments that violate WTO rules.

Because of its market size, the U.S. became a principal target for cases brought against it in the WTO. In its first 20 years, from 1995—2015, the WTO appointed “judges” ruled on 529 disputes of which 129 (one-quarter) were brought against the U.S. that lost in 90% of these cases. The United States became the universal bazaar. This was accompanied by China’s admission to the WTO in 2001, following Clinton’s reversal of its previous trade status with the U.S., with special exemptions from some WTO rules as a “developing country” – a status it continues to hold.

With these twin victories in the space of 12 months, perhaps Clinton began to see a story about himself and his presidency that went like this. My task is to take a progressive tradition rooted in the New Deal and bring it forward into the new world of globalization. A set of grand ideas are needed to shepherd this and make the fruits of global prosperity available to everyone not only in the United States but in the world. With free trade globally there is a chance to bring the world’s poor into a new era of prosperity. At home prosperity will be widely distributed without having to rely on old fashioned government transfers – “welfare.” We are closing the gap between systems set up for a world a half century or more past and the new global imperatives: promoting liberal democracy, free markets and free trade, while transporting and transforming institutions into a global era that is historically and technologically determined.

No doubt he had many discussions with his compatriot, Prime Minister Tony Blair of Great Britain, who had a similar story to tell about his concept of New Labor that sought to bring his party’s ideas into a new global order that transcended that bordered island’s policy institutions established after World War II. With the legitimating wind at his back of the European Union’s comparable supranational authority, Blair would find much in common with Clinton’s use of globalization to justify policy initiatives that erased what they saw as outmoded structures from another historical era. The two leaders launched a project called the “Third Way” with conferences, policy papers, and media commissions to promote the promise of globalization.

The idea of globalization allowed Clinton to shape a world of public policy that closed the gap between inherited New Deal policies based on national borders and the new realities of an interdependent and open border world. He could even justify further deregulation based on the idea that global markets render our bordered regulations archaic, ineffective, and counter-productive. This became a way to sell deregulation without relying on that moldy conservative argument about government intrusion. He could, in fact, even justify repeal of that last bastion of New Deal financial regulation – Glass Steagall – based on the argument that global markets have rendered it obsolete. He did not have to rely on Republican anti-regulation ideology but justified it to himself and a new constituency of elite opinion leaders, who crossed political labels, by linking it to globalization’s allure. In this he had supportive powerful financial forces behind him with Wall Street’s newly established alliance with the “new” Democrats. As an unintended consequence, Clinton and the Democrats stumbled onto a political coalition to replace the New Deal’s: Wall Street, Silicon Valley, global corporations, celebrities, and highly educated professionals.

Toward the end of his eight years in office, President Clinton responded to the critics of his legacy with a formulation he used in his 1999 State of the Union address and repeated frequently: “When you come right down to it,” he said, “now that the world economy is becoming more and more integrated, we have to do in the world what we spent the better part of this century doing here at home. We have got to put a human face on the global economy.” So, the two bold conceptions are merged: the New Deal and globalization. However, his formulation is curious in that the New Deal was comprehensive it its programs for the middle class, regulatory protections, and investments in the nation. It was more than just a “human face” that implies some public image, messaging, or branding make-over rather than concrete proposals to ensure globalization’s fruits are not unequally allocated.

Nevertheless, President Clinton had found the story of his administration in one phrase: “Building a Bridge to the Future.” He also found a highly lucrative mission in his post-presidency.

The baton was passed to Barak Obama and his ill-fated Trans-Pacific Partnership that became a flashpoint – along with NAFTA and the WTO – for attack from both the left (Sanders) and the right (Trump) in 2016. I am sure neither Blair nor Clinton envisioned either Brexit (and Boris Johnson) or Trump as outcomes of their globalization project.

The opposing language to globalization, neoliberalism, came to refer to the ascendance of the free market over social democracy in Europe and liberal democracy in the United States. “Neoliberal re-regulation is not the negation of restrictions on capital,” argued John Weeks in his 2018 David Gordon Memorial Lecture. “Rather, it is the implementation of active policies to limit the scope for governments to act and intervene in economic, social, and political spheres.” (I would add this exception: when capital becomes distressed it appeals to government for bail outs of considerable size and scope, with no quid-pro-quos, as it temporarily abandons its anti- nation state posture). Summing up nicely, Weeks notes that “during the New Deal and social democracy in Europe governments regulated capital. In the neoliberal era capital regulates government.”

That democracy is stressed needs no elaboration. But the stress imposed on economic democracy by globalization does since its diminution affects political democracy. The bordered nation state was no match for the borderless global system even if it wanted to challenge it. And it did not. Rather it became an enabler, cheerleader, devotee of the very instrument that denuded its authority to protect its citizens from threats to the public and social order. Inequality’s worsening, – partly a consequence of globalization – fairness and equity in economic outcomes, though nominally acknowledged by politicians, feed the bleak economic realities of those left off the high-speed globalization train. Those left off know it all too well. For elites to dismiss them as simply “rural,” ignorant, unwashed, racist is a mistake that will continue to have consequences for liberal political democracy.

From the vantage point of the 2016 and 2020 U.S. elections, Bill Clinton’s bridge to the future via globalization appears to need repair at best or may become too hazardous to cross at all. The Brexit vote in the United Kingdom was the canary in the mine. The shakiness of Europe’s version of globalization in the form of the European Union, and the attendant rise of nationalist political forces on the European continent, are challenging the EU project at its foundation. And then there is the United States. There are significant fault lines in the previous decades’ consensus. Are we witnessing a worldwide historical arc of transformation?

Whether the resolution of this shift in political culture finds its footing in a progressive democratic form or in a nativist conservative one is unknown but is critical to the world’s future. Only a progressive politics – that restores government and the nation to its rightful place by constructing an envelope around globalization’s excesses – has a chance of holding off an authoritarian challenge from the right that can lead to a decommissioning of democracy. Defeating Trump is the first step; but then the task of taking on the globalizing elites becomes the real test for the future of liberal democracy.

Decades in the making, globalization’s dismantling will require an equivalent decades-long, sustained project of reversing neoliberal political and ideological dominance. Is there such a prospect? One is incubating but is challenged by a moth-balled governing cadre poised to “restore American leadership” in the world. Is this coding for a renewed and deeper globalization?