There’s one other theme from the Introduction to my book that I want to raise in this cycle of posts before moving on to Part I.

But first, maybe it’s relevant to my theme to take a quick look at wider news. I heard they had an election over in the USA, but it seems all isn’t yet settled and there are competing narratives about the result and its implications. Was the Democratic victory fraudulent or bona fide? (Clue: the latter). Did the left of the Democratic party nearly lose the election for it, or help push it over the line? Was the Trump presidency a strange anomaly or a harbinger of future political turbulence? Is the onus on ‘liberals’ to understand why so many people voted for Trump, or on ‘conservatives’ to understand why so many more didn’t? Is Trumpism destined to live on in the hearts and guns of the now semi-mythical ‘white working class’ – or is it actually a project of the white middle class, or some other group? And, if implemented, will Biden’s climate policies be able to change the game, or will they meet an impossible trade-off between fossil-fuelled capitalism and climate-induced degrowth?

Closer to home here in the UK, a Biden presidency may spell the end of the no deal Brexit brigade’s ascendancy. Expect a last minute trade deal on disadvantageous terms with the EU trumpeted as a great victory, through which the remaining vital organs of British capitalism will be carved up between larger global players – perhaps with the UK itself as a political entity the ultimate casualty. Meanwhile, with the Northern Independence Party forming and opposition growing within the Labour Party against its lurch to authoritarian centrism, the supersedure state of which I speak in Part IV of my book may be upon us sooner than I thought.

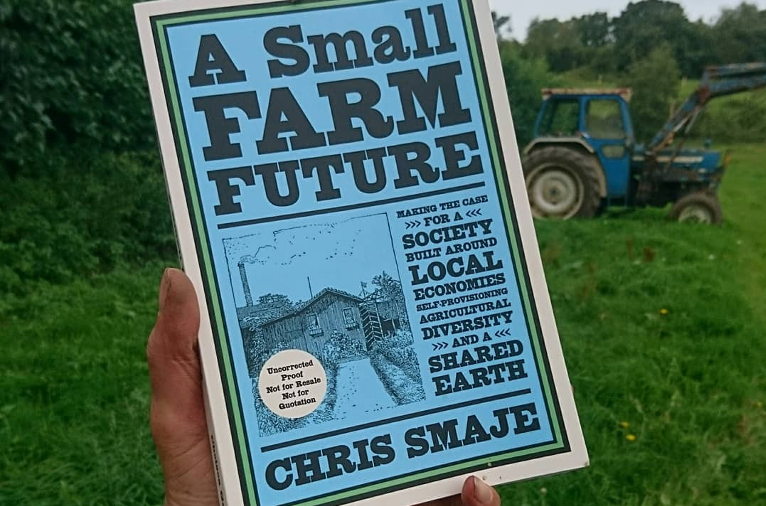

Ah yes, so finally on the news front … my book. It was briefly riding as high as about #7,000 on the Amazon bestseller list, which I’m told isn’t bad going at all. See the My book page for some online resources (including how not to buy it from Amazon), recent reviews and other exciting news about said tome. And do please consider writing an online review, especially if it’s positive.

So … I’ll be watching with interest to see how the various narratives described above unfold, while hoping that the US (and the UK) will emerge from their present imbroglios without irreparable damage. But now I want to turn to another case of divergent narratives that I broach in the Introduction to my book.

On page 7 I write “Throughout the world, there are long and complex histories by which people have been both yoked unwillingly to the land and divested unwillingly from it”. These histories fuel many different and often competing stories about land, food and belonging, but also a kind of modern historical forgetfulness about the complexity of human relationships with land (and water) through time.

I argue throughout the book that it’s necessary to overcome this forgetfulness, and recover the stories of land and loss that lie behind it in all their complexity and dissonance. Without this, I doubt we’ll be able to make wise decisions that will really work locally about the many pressing issues we face today. We’d probably resort instead to superficial morality tales that have long outlived their usefulness drawn from an (also superficial) grasp of history. And such tales are legion. Here in England, they include the notion that enclosure spelled the end of peasant agriculture, that industrialization ultimately liberated people from poverty, and that this industrialization was some endogenous process of modernization and development that had nothing to do with England’s colonial exactions elsewhere in the world.

I’d hope people reading my book would come away from it with a sense that such stories are oversimplifications that no longer serve us. But the book makes limited headway in telling better historical tales, largely because I only had so many pages to play with and the world is a large and complex place. But those deeper tales do need to be told. Carwyn Graves’s interesting review of my book from a Welsh perspective is a good example of how one might begin that telling.

In the meantime, I’d suggest – to paraphrase a recent British prime minister – that “no history is better than bad history”. In other words, given the unique set of problems people presently face, it’s as well to try to be as open-minded as possible about how to solve them rather than drawing on bad historical analogizing to close off particular approaches. Here are some common examples of the kind of bad analogizing I have in mind:

- This country/region won’t be able to feed itself in the future, because it never did in the past

- A small farm future would be unpleasant because the small farm past was

- There have been people in the past who were happy to quit peasant farming, so nobody will be happy to take it up in the future

- Nobody will renounce mass consumer society for a small farm future of simple living in the future, because in the past people opted for the former over the latter

- Technology will solve people’s present problems because it solved people’s past ones

- Any future attempt to create local agrarian autonomy will be crushed by centralized states, as in the past

- Positive change will be led by the downtrodden, because past experience shows they’re the ones who truly appreciate how the present system works

I’m not saying that such statements will inevitably turn out to be wrong. I’m just saying that they might turn out to be wrong, and a superficial analysis of past analogues to our contemporary questions is a poor guide to how they will, in fact, turn out.

One of the defects of the historical analogizing I’m criticizing is that it’s ill attuned to dissonance, contradiction and competing narratives. So while, for example, it’s true that Britain has long been a net importer of food, throughout this time there have been people arguing that it can and should largely feed itself. They weren’t necessarily wrong, they just lost the political argument. Maybe their successors will be luckier. Perhaps there are implacable forces in history, but I suspect not as many as at first it seems when so many people jump on the bandwagon of the ‘had to happen’ on the flimsy evidence of the ‘did happen’. The past could have led to a different present. The present may lead to a future beyond our current imaginings.

So let your history run deep, and your horizons scan wide. Next up: Part I.

Ed.note: The previous use of an image of a six-horse team mowing hay in Pennsylvania was not suggested by the author and is not germane to any of the arguments in this post about a small farm future, or what that future might look like. The author is not stating that that future will only include horse power on farms, although that might be an option in certain instances. The image was chosen by the editor, who takes responsibility for it. Since the image could lead to the misunderstanding mentioned above, it has been removed.