The survival of life on earth depends on México’s dark fossil sunlight never seeing the light of day.

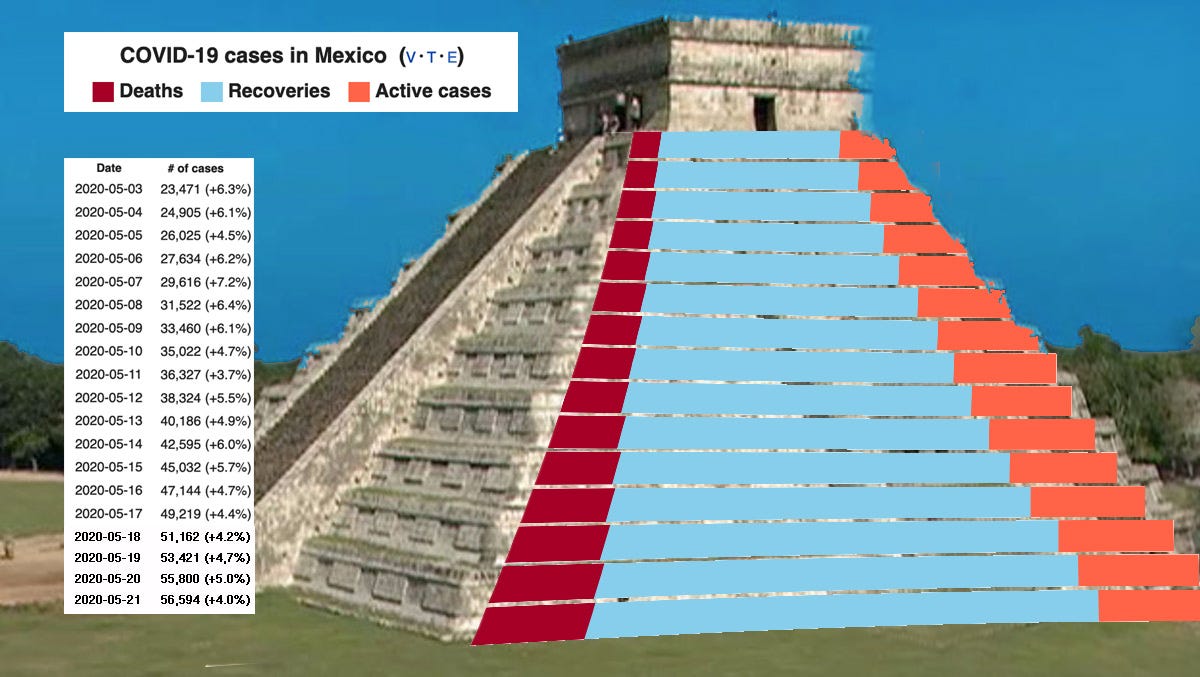

The 40 crematoria in México City are working night shifts but can’t keep up with the flow of Covid bodies arriving from hospitals, nursing homes, prisons, and retirement enclaves. Television footage shows the deliveries of bodies going non-stop as the country’s death toll continues to climb. The actual mortality rate could be five times higher than official figures suggest.

“The ovens never stop burning,” said a Sky News report, as the footage showed thick black smoke billowing from “where they are cremating bodies on an industrial scale.”

In the rural Mexican south, where I’ve quarantined myself these past nine weeks, the spread of Covid is distinctly slower. The indigenous communities here in the Yucatán are different than you’ll find in other places. The first spoken language in most homes is a modern extension of the local vernacular used pre-Conquest with roots in Nabʼee Mayaʼ Tzij (“the old Maya Language”) extending back some 5000 years.

Here the names of the towns are written in mayab tʼàan. “Mayan” is the native tongue of the majority of México’s 6 million indigenous speakers, compared, by way of reference, to 170,000 native Navajo and 30,000 native Sioux speakers. Of course, “Mayan” is not homogenous like Welsh in Wales or Maori in Aotearoa. Guatemala formally recognizes 21 Mayan languages by name and Mexico recognizes eight more just here in the Yucatán. While most Mayan dialects are robust, of the 287 individual languages once present in México, four are already extinct, 87 are in trouble and some 60 are recently departed or dying.

This part of the world was slow to give up its old ways. Climate change and capital accumulation by hierarchies augured cyclical collapse, centennially or millennially. Mass migrations from failed cities to the rural countryside — retreating to the sustainability of small plot agroforestry and integrated animal husbandry — was a viable strategy that repeatedly preserved both culture and language. The Classic Era came and went but Maya population did not decline, it concentrated, then dispersed, then concentrated again. As my lifelong friend, Brother Martin, pointed out in a recent comment to one of my posts:

Sunflowers and salamanders do not practice “capitalism.” They practice “capital accumulation,” the amassing of energy and resources in order for growth and renewal to take place. What those of us who decry “capitalism” are against is not “capital accumulation,” but, to paraphrase Prof. Richard Wolff, a societal organizing principle that gives priority to the protection of money and property, and to the humans who claim ownership of large quantities of money and property.

In the case of the Maya city-state empires, what was fragile — both socially and ecologically — were concentrations of wealth and power in the hands of a select few, who inevitably mismanaged both. Abuses can still happen at a decentralized scale but consequences are more limited and the feedback more immediate. Decentralized systems tend to be anti-fragile. We are seeing that now with the impact of Covid on cities and in the ecological rejuvenation of remote natural areas.

Mexico’s current doubling rate is two weeks

Maybe periodic subjugation and collapse predisposed the Mexican character towards a rebel pride. The street I live on is named for the shipwrecked Spaniard, Gonzalo Guerrero. According to fellow shipwrecked sailor, Gerónimo de Aguilar, Guerrero “went native,” married native women, wore traditional native apparel, and taught effective military defense tactics against the Spanish. Maya resistance, in small bands, selected dense forests and impassible swampland to lay in ambush for the invaders and then fade away before they took casualties. It was a tactic that later worked well for Geronimo and Cochise. The Spanish brought armored Andalusian warhorses, Toledo broadswords, halberds, crossbows, matchlocks and light artillery. Maya warriors fought with flint-tipped spears, bows and arrows, and stones, and wore padded cotton armor, but their guerrilla tactics succeeded and their losses were few, until epidemics of European plagues cut their ranks and reduced them to poverty. The last independent and unconquered native bastion, at Nojpetén, surrendered to the Spanish in 1697.

By the early 19th century the Spanish Empire had turned the peninsula into large maize and cattle plantations and exporting sawmills, with luxurious haciendas tended by mestizo slaves. If you look at the printed currency or the names of streets today, they tell a different story. One name and image frequently seen is that of Benito Juarez, the first mestizo president and a populist reformer. France invaded México in 1861 on a pretext of collecting defaulted loans from Juarez’s government but really had been put up to it by Mexican right-wing interests seeking to restore Spanish-style monarchy. They set Maximilian I on the Mexican throne.

The United States, engaged in its own civil war at that time (1861–65), did not attempt to counter the French, as the Monroe Doctrine would demand. Cinco de Mayo (May 5) celebrates the day México kicked France’s ass. That was lucky for Lincoln, because France had planned from its base in México to enter the American Civil War in support of the Confederacy and the plantation system. That plan was put awry by the Mexicans.

A Restored Republic (1867–76) brought Benito Juárez back as president. Then his successor was overthrown by a military coup that lasted until 1910 when Porfirio Díaz’s clearly fraudulent reelection touched off the Mexican Revolution. The war killed a tenth of the nation’s population (much as Covid may) and drove many Mexicans across the border into the United States. It also launched the t-shirt careers of Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa.

Cinco de Mayo was lucky for Lincoln, because France had planned to enter the American Civil War on the side of the Confederacy.

Following the revolution, the 1917 Constitution gave rights to labor unions and worker’s cooperatives, instituted land reform, breaking up many of the old hacienda relics, and began neoliberal economic policies. From 1929, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) controlled most national and state politics, and among other reforms, nationalized the railroads and oil industry in the 1930s. That brought about another popular name for places, “Lázaro Cárdenas.” General Cárdenas created the Partido de la Revolución Mexicana (PRM), giving representation to the poor, unionized workers, professionals, and the Mexican army. Cárdenas’ co-optation of the army was a deliberate move to prevent more coups d’état.

Early in his presidency, Cárdenas brought foreign oil companies into collective bargaining with the labor unions. When they hit an impasse, the government’s Council of Conciliation and Arbitration supported the workers. The companies refused to pay living wages so Cárdenas cancelled their concessions and the oil companies sued. The Supreme Court, relying on the 1917 Constitution, ruled for the workers and the government. Emboldened by this ruling, Cárdenas nationalized the assets of the oil companies and formed Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex). The foreign oil companies destroyed what drill rigs and refineries they could, took all their engineers with them, and left.

In 1938, the British severed diplomatic relations and launched an economic boycott of México. President Franklin Roosevelt was tempted to do the same, beginning with closing Texas refineries to Mexican crude and mustering troops along the border. In 1939 Cárdenas sent Roosevelt the first sample of Mexican-distilled petroleum. Needing Mexico and its oil for the war, Roosevelt relented and reopened trade.

Perhaps most significantly, Cárdenas began transforming his newfound oil wealth into programs of public works; building roads, rural clinics, and schools. Cárdenas died of cancer in 1970 at the age of 75. It was 5 years later that the shrimper, Rudecindo Cantarell, reported to Pemex that his net had gummed up with oil while fishing in the Gulf of Mexico. The fisherman had discovered an oilfield second only to Ghawar in Saudi Arabia in its vast reserves.

México used the oil wealth of the Cantarell field, and whatever it could borrow from international development banks, to create its massive tourist and manufacturing industries and begat the Mexican Miracle (although it is commonly said by Mexican construction workers, who are paid in cash, that money laundering for drug cartels played no small part).

Cancún was transformed from a beach at the edge of a jungle into a destination for hundreds of daily passenger jets dumping European kitesurfers and co-ed spring-breakers into its turquoise bay. Factories for automotive and machine parts and cheap furniture bloomed along the Rio Grande. México lifted itself from poverty.

All those tourist dollars changed something else, too. Once México was known as one of the most important food producing countries of the world. Today México imports all of the principal crops that its population eats: beans, corn, rice, wheat and vegetables. It has become a service and manufacturing economy, a.k.a. neoliberal export capitalism.

In modern México, the periodic famines that Rudecindo Cantarell and his parents knew and expected are hard to imagine today. Food is so cheap, plentiful, and subsidized that obesity is a greater concern. All of this might be well and good if it were sustainable, but México’s reliance on endless-growth economics now hinges upon an ancient storehouse of energy that was once the forests and shallow seas of Pangea before the Chicxalub meteor struck, and on the unique geological conditions that allowed that sunlight to be preserved until now.

The survival of life on earth depends on México’s dark fossil sunlight never seeing the light of day.

In 2004, Pemex was pleased to announce that its oil production would continue for many years to come. Pemex’s head of exploration and production, Luis Ramirez, was quoted in the daily newspaper El Universal as saying that Pemex had mapped seven new offshore blocks with large pools of oil and natural gas, more even than México’s proven plus probable reserves at that time.

“This will put us on a par with reserves levels of the big players like Iraq, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait or Iran,” Ramirez said. “What’s more, we would be in a position to reach production levels like those of Saudi Arabia, which produces 7.5 million barrels per day, or Russia, which produces 7.4 million.”

In grifting, this would be called the long con. There were no proven reserves of that scale, only some prospects for exploration. But Ramirez, the con artist, had baited the hook.

The mark, México’s president, was drawn in on the promise of vast, easy wealth for his nation. As in all cons, the mark was hooked by his own greed. The grifter then asked for help to provide tangible proof that the wealth was there. Outside investment would be needed to drill exploration wells more than a mile deep in the Gulf. Just a few billion up front. But the good news? No money need come from México, the grifter said.

At a hushed-up retreat at an old hacienda in Yucatán, George W. Bush leaned on Felipe Calderón to go along.

Mexican Presidents Vincente Fox, Felipe Calderón, Enrique Peña Nieto, and Andres Manuel Lopez Obredor, despite committing to climate protection, all fell for the lure of easy money. They began auctioning off blocks of offshore leases for exploration by anyone with the technology and money required. AMLO, the son of a petroleum worker, opposed these sales as a betrayal of Cárdenas’ memory. He wanted more wells, climate be damned. He just didn’t want foreign companies to control them.

AMLO’s political party, MORENA, (Movimiento Regeneración Nacional), a Cardenist, Juarist revival, successfully blocked any move by his predecessors towards foreign investment in the National Assembly. As the giant Cantarell field went into steep production decline during the Peña-Nieto years, Pemex lacked the capital and expertise to explore for comparable replacements, oil revenues fell, and a financial crisis emerged. The Mexican government relied desperately on 61% of Pemex’s gross oil income to balance its spending and attract foreign investors for a multiplicity of large projects.

Its wells gone dry, by 2019, Pemex imported roughly 70% of its daily gasoline consumption, mostly from the US. In each of the last two quarters leading up to its Covid moment in January 2020, Pemex posted a net loss of more than 80 billion pesos ($4 billion dollars).

Industries may be shuttered but not all fracked gas can be stopped, and storage is full. So, it must be flared, erasing the climate benefit of the shutdown.

As long as oil prices were high and Mexico could still scrape enough off the bottom to keep exporting, the situation was manageable. A typical offshore project in the Gulf of Mexico has a breakeven production cost between $40 and $80 per barrel and, having crushed its labor unions, Pemex could, in the choicest spots, bring up oil for half that. But then came a cold, dark January. Brinkmanship between Saudi Arabia and Russia over OEC quotas killed not just the fracking and tar sands boom in the US and Canada, but a lot of oil-exporting countries’ entire economies. A negative oil price stranded crude on tankers and in tank farms everywhere and forced companies to massively flare unstoppable natural gas wells and shut down pipelines.

Last week Mexican crude went for $6.55 per barrel in international markets, according to Pemex. The company’s Moody’s and S&P ratings have been downgraded to junk status, below investment grade. Fortunately, Pemex undertook a complex hedging operation that allows it to keep selling some of its oil at its settled futures price, $49 a barrel — rather than $6.55. That’s bought AMLO a little more time, but apparently he doesn’t yet recognize he’s been conned. He is still throwing good money after bad.

AMLO has launched a Pemex rescue attempt. He’s poured tax revenues totaling 113 billion pesos ($5.1 billion dollars) into ramping up production at Pemex’s remaining oil fields. At the same time, he’s shut off 15% of his government’s income by eliminating taxes and tariffs on Pemex of 65 billion pesos ($3 billion) per year. Lastly, he’s prohibited renewable energy grid-ties, killing massive new projects for wind and solar around the country (a move that was later overturned in court).

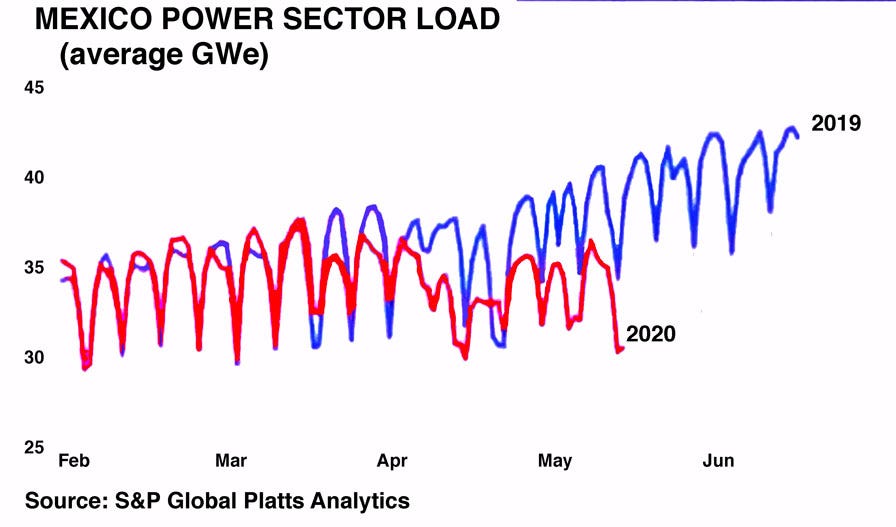

The son of the oil worker has long opposed renewables, claiming them intermittent and unreliable. México has a total installed capacity of 6.2 GWe of wind and 5.5 GWe of solar. The average electrical generating costs for México’s state-owned utility, CFE, are above $120/MWh for coal, diesel and fuel oil and below $20/MWh for grid-tied renewables.

Pemex typically gets a boost in revenues when it exports natural gas to meet the summer cooling demands of the US Southwest, reversing its trade deficit for gasoline and diesel imports and turning a nifty profit. One could call it ironic that the worse global warming gets, the more money México makes off its fracked gas sales, but ironic here is a euphemism for evil.

As June, 2020 approaches, Covid demand destruction is poised to wreck that pattern, but by how much is unknown. The weather will still be hot. Residences will still need to be cooled. The question is how much commercial space that Covid-assailed chain retailers like malls and hospitality providers will be willing to spend money on to keep cool.

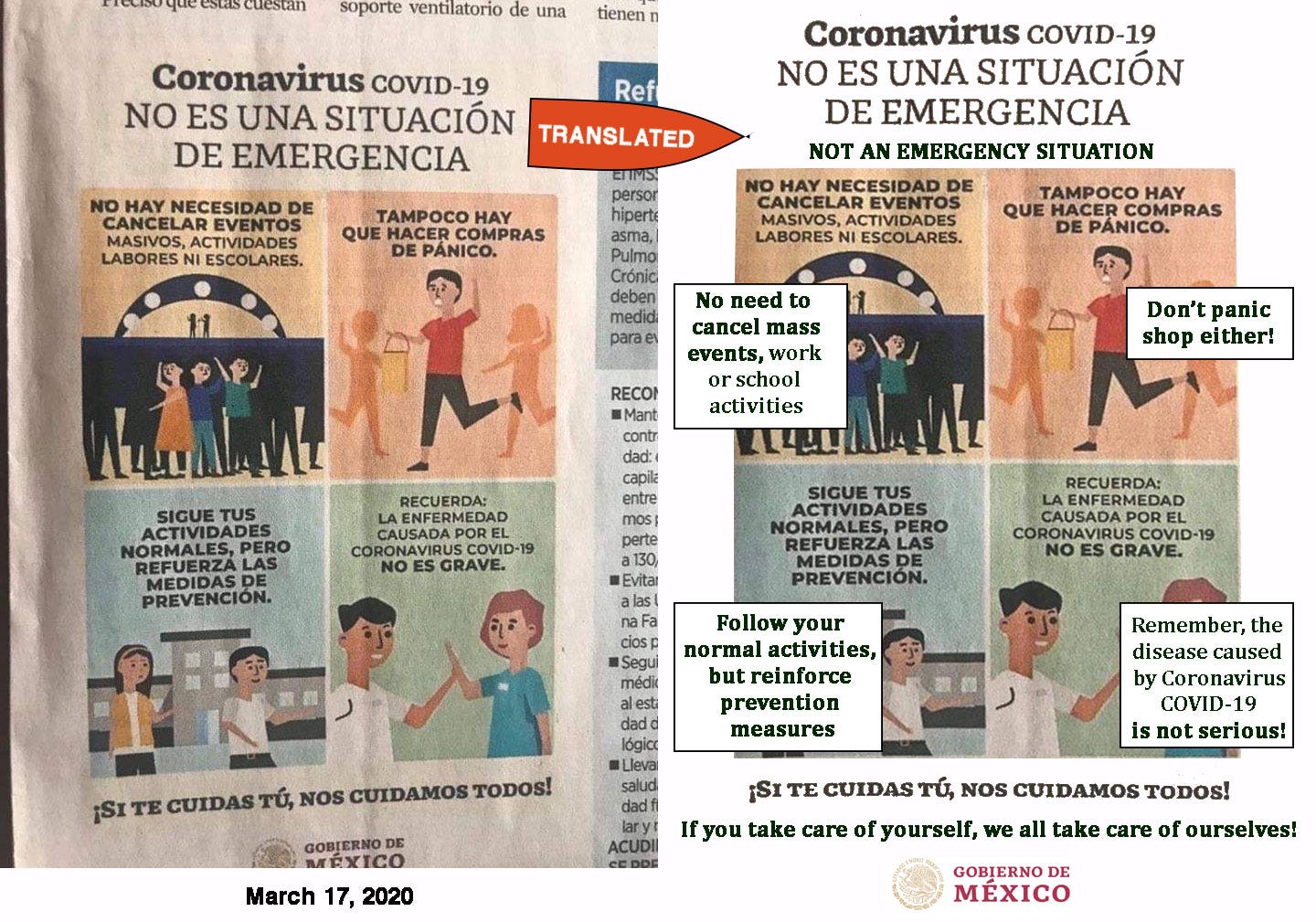

When Covid first arrived in México in January, AMLO compared it to the seasonal flu and said that with luck and a faith in God his country would weather the impact. He abjured social distancing, quarantines and other mitigation measures and directed his agency heads to do the same. Casualties were downplayed, and then hidden. Testing and contact-tracing were virtually non-existent.

Like many other governments, México seemed to rely on the myth of herd immunity, which doesn’t work for coronaviruses because of the mutation rate — RNA transcriptions don’t get the molecular fact-checking that DNA viruses do. Relying on herd immunity is a prescription for infections in the billions and deaths in the hundreds of millions.

Ignoring the unique lethality of Covid comes at a cost, as the United States has been learning, although that news has yet to reach regions that are only barely afflicted yet and prematurely reopening. S&P Global Ratings forecast México’s GDP to have the largest contraction of all Latin America’s major economies. I’m willing to bet Brazil will give them a run for their money.

Will tourists be returning to México? Not any time soon, at least not in large numbers. Will manufacturing resume along the Rio Grande? Again, not very quickly, and then only anemically at first. México is going to have to face some difficult choices soon. It needs to go back to being a food-producing country. It needs to restore its lost natural resources and protect what remains. It needs to remember what its indigenous ancestors did when the climate changed, civil collapse came, or invasion threatened. They dispersed and downsized. They developed appropriate strategies and tactics. They went back to tree crops, chickens and pigs. They self-isolated. And because of that, they are still here today.

The Mayan traditional milpa rotation system, by converting annual photosynthetic slash to biochar fertility, drew carbon from the atmosphere and locked it safely away for millennia, cooling the climate.

If México actually took that path— to, for instance, abandon its sinking, stinking, blighted District Federal and let the great Lake Texcoco refill its original mountain basin, recover the chinampas of Zumpango, Xolchimilco and Chalco, and reforest the volcanic highlands — it would accomplish more than merely to avert the political collapse its present trajectory augurs. It would set an example for its neighbors and the rest of the world for how to get out of this century alive.