Ed. note: Don Fitz (fitzdon@aol.com) is on the editorial board of Green Social Thought, where a version of this article was originally copublished with MR Online. His book, Cuban Health Care: The Ongoing Revolution, is forthcoming by Monthly Review Press in June, 2020.

Ed. note: Don Fitz (fitzdon@aol.com) is on the editorial board of Green Social Thought, where a version of this article was originally copublished with MR Online. His book, Cuban Health Care: The Ongoing Revolution, is forthcoming by Monthly Review Press in June, 2020.

The current COVID-19 pandemic challenges us to develop the ability to utilize vastly less resources while simultaneously being compassionate, and, above all, competent. By the beginning of this millennium Cuba had attained a lower level of infant mortality than the US and a longer life expectancy while spending five percent annually on health care compared to the US. But, could it actually respond better to the current health crisis?

Cuba’s preparation for COVID-19 began on January 1, 1959. On that day, over sixty years before the pandemic, Cuba laid the foundations for what would become the discovery of novel drugs, bringing patients to the island, and sending medical aid abroad.

For twenty years before the 1959 revolution, Cuban doctors were divided between those who saw medicine as a way to make money and those who grasped the necessity of bringing medical care to the country’s poor, rural, and black populations. An understanding of the failings of disconnected social systems led the revolutionary government to build hospitals and clinics in under-served parts of the island at the same time it began addressing crises of literacy, racism, poverty, and housing.

By 1964, Cuba began creating policlínicos integrales, which were recreated as policlínicos comunitarios in 1974 to better link communities and patients. By 1984, Cuba had introduced the first doctor-nurse teams who lived in the neighborhoods they served. This continuing redesign of Cuban primary and preventive health has lasted through today as a model.

It had an overarching concern with health care, even though it had never escaped from poverty. This resulted in Cuba’s eliminating polio in 1962, malaria in 1967, neonatal tetanus in 1972, diphtheria in 1979, congenital rubella syndrome in 1989, post-mumps meningitis in 1989, measles in 1993, rubella in 1995, and tuberculosis meningitis in 1997.

The Committees for Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) became a key part of mobilization for healthcare. Organized in 1960 to defend the country from a possible US invasion, the CDRs took on more community care tasks as foreign intervention seemed less likely. They became prepared to move the elderly, disabled, sick, and mentally ill to higher ground if a hurricane approached. They currently help in removal of mosquito breeding places during episodes of dengue fever, participate in health education programs, ensure distribution of children’s vaccination cards, and help train auxiliary staff in oral vaccination campaigns.

AIDS in a Time of Disaster

Two whammies pounded Cuba in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The first victim of AIDS died in 1986, and Cuba isolated soldiers returning from war in Angola who tested positive for HIV. A hate campaign against Cuba claimed that the quarantine reflected prejudice against homosexuals. But the facts showed that (1) soldiers returning from Africa were overwhelmingly heterosexual (as were most African AIDS victims), (2) Cuba had quarantined dengue patients with no outcry, and (3) the US itself had a history of quarantining patients with tuberculosis, polio, and even AIDS.

The second blow landed quickly. In December 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed, ending its $5 billion annual subsidy, disrupting international commerce, and sending the Cuban economy into a free fall that exacerbated AIDS problems. A perfect storm for AIDS infection appeared to be brewing. The HIV infection rate for the Caribbean region was second only to southern Africa. The embargo simultaneously reduced the availability of drugs (including those for HIV/AIDS), as it made existing pharmaceuticals outrageously expensive and disrupted the financial infrastructures used for drug purchases. If these were not enough, Cuba opened the floodgate of tourism to cope with lack of funds. As predicted, tourism brought an increase in prostitution. There was a definite possibility that the island would succumb to a massive epidemic that would rival the effects of measles and smallpox which had arrived with European invaders to the New World.

The government response was immediate and strong. It drastically reduced services in all areas except two which had been enshrined as human rights: education and health care. Its medical research institutes developed Cuba’s own diagnostic test by 1987. Testing for HIV/AIDS went into high gear, with completion of over 12 million tests by 1993. Since the population was about 10.5 million, that meant that persons at high risk were tested multiple times.

Education about AIDS was massive for sick and healthy, for children as well as adults. By 1990, when homosexuals had become the island’s primary HIV victims, anti-gay prejudice was officially challenged as schools taught that homosexuality was a fact of life. Condoms were provided free at doctor’s offices. I witnessed the survival of the education program during a 2009 trip to Cuba; the first poster I saw on the wall when entering a doctor’s office had two men with the message to use condoms.

Despite high costs, Cuba provided antiretroviral (ART) drugs free to patients. One of the great ironies of the period was that those who screeched most noisily about Cuba’s “anti-homosexual” quarantines remained silent as the Torricelli Bill of 1992 and the Helms-Burton Act of 1996, designed to “wreak havoc” on the island, seriously hindered the government’s efforts to bring ART drugs to HIV victims.

Cuba’s united and well-planned effort to cope with HIV/AIDS paid off. At the same time Cuba had 200 AIDS, cases New York City (with about the same population) had 43,000 cases. NYC residents were far less likely to have recently visited sub-Saharan Africa, where a third of a million Cubans had just returned from fighting in the Angolan war. When the HIV infection rate in Cuba was 0.5 percent, it was 2.3 percent in the Caribbean region and 9.0 percent in southern Africa. During the period 1991–2006, Cuba had a total of 1,300 AIDS-related deaths. By contrast, the less populous Dominican Republic had 6,000 to 7,000 deaths annually. In 1997, Chandler Burr wrote in The Lancet that Cuba had “the most successful national AIDS programme in the world.” Despite having only a small fraction of wealth and resources of the United States, Cuba had implemented a superior AIDS program.

Dengue and Interferon Alpha 2B

The mosquito-borne dengue fever hits Cuba every few years. Its doctors and medical students check for fever, joint pain, muscle pain, abdominal pain, headache behind the eye sockets, purple splotches, and bleeding gums. What is unique about Cuba is that its medical students leave school and go door-to-door making home evaluations.

Students from ELAM (Spanish acronym for the Latin American School of Medicine) come from over 100 countries and speak with a huge number of accents. They have no trouble walking through homes, looking for mosquito-attracting plants, and peering onto roofs to see if there is standing water.

During a 1981 outbreak of dengue, expanded surveillance techniques included inspections, vector control education, spraying, and “mobile field hospitals during the crisis with a liberal policy of admissions.” Cuba also increased testing for potential cases during a 1997 dengue outbreak. Increased testing of hospital patients was combined with surveillance data to produce predictions concerning secondary infections related to death rates. These campaigns, which combined citizen involvement with health care professionals and researchers, have resulted in reduced incidence of dengue and decreased mortality.

In 1981, Cuba’s research institutes created Interferon Alpha 2B to successfully treat dengue. The same drug became vitally important decades later as a potential cure for COVID-19. According to Helen Yaffe, “Interferons are ‘signaling’ proteins produced and released by cells in response to infections that alert nearby cells to heighten their anti-viral defenses.” Cuban biotech specialist Dr. Luis Herrera Martinez adds that, “its use prevents aggravation and complications in patients, reaching that stage that ultimately can result in death.”

Since 2003, Interferon Alpha 2B has been produced in China by the enterprise ChangHeber, a Cuban-Chinese joint venture. “Cuba’s interferon has shown its efficacy and safety in the therapy of viral diseases including Hepatitis B and C, shingles, HIV-AIDS, and dengue.” Cuba has researched multiple drugs, “despite the U.S. blockade obstructing access to technologies, equipment, materials, finance, and even knowledge exchange.”

Ebola and International Aid

AIDS and dengue were problems that affected the Cuban population; but Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) was quite different. Viruses that cause EVD are mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa, an area that Cubans had not frequented for several decades.

When the Ebola virus increased dramatically in fall 2014, much of the world panicked. Soon, over 20,000 people were infected, more than 8,000 had died, and worries mounted that the death toll could reach into hundreds of thousands. The United States provided military support; other countries promised money.

Cuba was the first nation to respond with what was most needed: it sent 103 nurse and 62 doctor volunteers to Sierra Leone. With 4,000 medical staff (including 2,400 doctors) already in Africa, Cuba was prepared for the crisis before it began.

Since many governments did not know how to respond to Ebola, Cuba trained volunteers from other nations at Havana’s Pedro Kourí Institute of Tropical Medicine. In total, Cuba taught 13,000 Africans, 66,000 thousand Latin Americans, and 620 Caribbeans how to treat Ebola without themselves becoming infected.

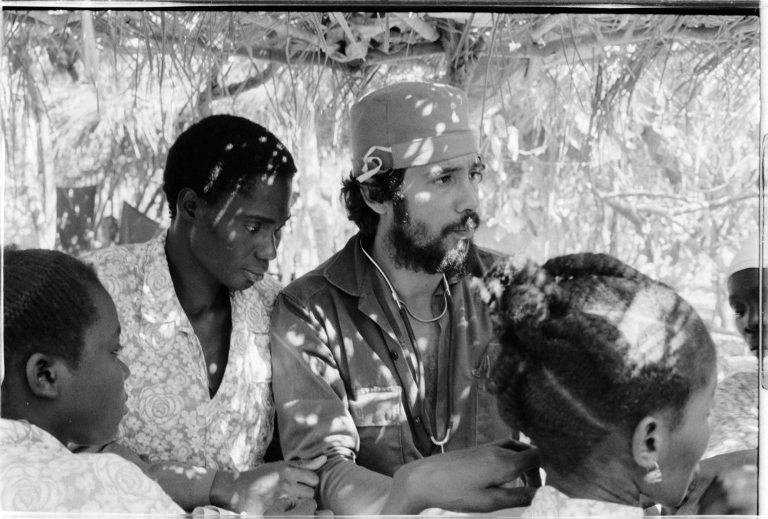

This was hardly the first time that Cuba had responded to medical crises in poor countries. Only fifteen months after the revolution, in March 1960, Cuba sent doctors to Chile after an earthquake. Much better known is Cuba’s 1963 medical brigade to Algeria, which was fighting for independence from France.

In the very first days of the revolution, there were insufficient medical staff and facilities in rural parts of Cuba that were predominantly black. It was perfectly natural for those who learned of lack of treatment and disasters that plagued other parts of the world to go abroad to assist those in need.

Revolutionary solidarity was often a collective family choice. Dr. Sara Perelló had just graduated from medical school when her mother heard Fidel say that Algerians were even worse off than Cubans and called on doctors to join a brigade to assist them. Dr. Perelló wanted to volunteer but was worried that her elderly mother suffered from Parkinson’s disease. Her mother responded that Sara’s sister and husband would help her as would the government: “Now the thing to do is go forward and don’t worry about your mother, who will be well taken care of.”

Cuban solidarity missions show a genuine concern that often seems to be lacking in health care providers from other countries. Medical associations in Venezeula and Brazil could not find enough of their own doctors to go to dangerous communities or travel to rural areas by donkey or canoe as Cuba doctors do. When Cuban doctors went to Bolivia, they visited 101 communities that were so remote that they did not appear on a map.

A devastating earthquake hit Haiti in 2010. Cuba sent medical staff who lived among Haitians and stayed months or years after the earthquake was out of the news. US doctors did not sleep where Haitian victims huddled, returned to luxury hotels at night, and departed after a few weeks. The term “disaster tourism” describes the way that many rich countries respond to medical crises in poor countries.

The commitment that Cuban medical staff show internationally is a continuation of the effort that the country’s health care system made in spending three decades to find the best way to strengthen bonds between care-giving professionals and those they serve. Kirk and Erisman provide statistics demonstrating the breadth that Cuba’s international medical work had reached by 2008: it had sent over 120,000 health care professionals to 154 countries; Cuban doctors had cared for over 70 million people in the world; and, almost 2 million people owed their lives to Cuban medical services in their country.

There is a noteworthy disaster when a country refused an offer of Cuban aid. After the 2005 Katrina Hurricane, 1,586 Cuban health care professionals were prepared to go to New Orleans. President George W. Bush rejected the offer, acting as if it would be better for American citizens to die than to admit the quality of Cuban aid. This decision foreshadowed the 2020 behavior of Donald Trump, who searched for a treatment for COVID-19 while pretending that Interferon Alpha 2B does not exist.

Contrasts: Cuba and the United States

These bits of history are background for contrasts between Cuba and the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those of us old enough to remember that in the 1960s, we could still have a relationship with a doctor without an insurance company interceding can appreciate that social bonds between physicians and patients were eroding in the United States at the same time they were being strengthened in Cuba.

Testing. Since Cuba brought both AIDS and dengue under control with massive increases and modifications of testing, it was well prepared to develop a national testing program for COVID-19. Similarly, China was able to quickly halt the epidemic, not simply from lockdowns, but also because it quickly tested suspected victims, took necessary steps for isolation and treatment of those found to be positive, and tested case contacts who were asymptomatic.

It is no accident that the United States is a global leader in neoliberal efforts to reduce or privatize public services, proved incapable of mounting an effective testing campaign, and, by the end of March 2020 was on the way to leading the world in COVID-19 cases. In mid-March, the United States had been able to test 5 per million people, though South Korea had tested more than 3,500 per million.

Symptomatic of governmental incompetence in the United States was Trump’s putting vice-president Pence in charge of COVID-19 control. It was Pence, who as Indiana governor, had drastically cut funds for HIV testing, thereby contributing to an increase in infections.

Costs of care and medication. Medical care in Cuba is a human right with no costs for treatment and only very small charges for prescriptions. Pharmaceutical companies were some of the first industries nationalized after the revolution. US policies routinely hand over billions of tax dollars to Big Pharma, which routinely gets away with gouging citizens mercilessly.

There are no insurance companies in Cuba to add to medical expenses and dictate patient care decisions to doctors. Even if testing becomes free in the United States, people must still decide if they can afford treatment for COVID-19. Those who think that their insurance will cover their COVID-19 bills, “may receive a large out-of-network bill if the ER has been outsourced to a physician staffing firm that is not covered by the insurance.”

Protecting workers. When natural disasters halt work, Cuban workers receive their entire salaries for one month and 60 percent of salaries after that. Cuban citizens receive food allotments and education at no cost, and utilities are extremely low. Cuba was able to shift production in nationalized factories so quickly and was able to churn out so much personal protective equipment (PPE) that it could send it to accompany the medical staff going to Italy when it was the pandemic’s center.

In the United States, there were nearly 10 million unemployment compensation claims by the end of the first week in April, and the country is not well-known for helping the unemployed by increasing taxes on the rich or reducing the military budget. There could be over 56 million “informal workers” in the United States who are not entitled to unemployment benefits. Forcing many US citizens to go to work because they cannot afford to go without basic necessities threatens the entire population with further spread of the pandemic. US health care workers have been short of PPE, including masks, gowns, gloves and test kits. Yet, President Trump is allowed to hold ventilators as “rewards” for states whose governors write that they appreciate him.

Comprehensiveness of health care. The Cuban revolution immediately reorganized the country’s disconnected health services and today has an integrated system beginning with neighborhood doctor-nurse offices tied into community clinics linked to area hospitals, all of which are supported by research institutes. The health system is connected to citizens’ organizations that have decades of experience protecting the country. This “inter-sectoral cooperation” is a keystone of health care. In Cuba, it would be inconceivable to have fifty different state policies that may or may not be consistent with national policies and may allow counties and cities within them to have their own procedures.

Instead of integrating plans for an effective approach to combating disease, the United States dismantles and/or privatizes whenever it can. Trump disbanded the pandemic response team, tries to underfund the pandemic prevention work of the World Health Organization, and sought to weaken nursing home regulations, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health.

Lest anyone think that this is peculiar to Republicans, please remember that Democrats have long been in the forefront of neoliberalism and utilization of the “shock doctrine” approach that Naomi Klein described. Both parties have contributed to dismantling environmental rules so desperately needed.

Rebecca Beitsch reported on March 26 that “The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a sweeping suspension of its enforcement of environmental laws, telling companies they would not need to meet environmental standards during the coronavirus outbreak.” Not wanting to be left out, “the oil and gas industry began asking the federal government to loosen enforcement of federal regulations on public lands in response to the coronavirus pandemic.” They sought an extension of two-year permits and the ability to hold onto unused leases. If pandemics such as COVID-19 recur in the future, will added pollution and climate-related diseases weaken human immune systems, making them more vulnerable to infections?

If so, universal medical coverage would be essential to protection for tens of millions of Americans. A recipient of huge donations from medical and pharmaceutical companies, Joe Biden has supported efforts to undermine social security and “suggested he would veto any Medicare for All bill that the House of Representatives passed.”

The Reality of Preparing to Deal with Medical Crises. Pascual Serrano noted that Cuba had already instituted the Novel Coronavirus Plan for Prevention and Control by March 2, 2020. Four days later it updated the Plan by adding “epidemiological observation,” which included specific measures like temperature taking and potential isolation, to infected incoming travelers. These occurred before Cuba’s first confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis on March 11. By March 12, after three Italian tourists were identified as having symptoms, the government announced that 3,100 beds at military hospitals would be available. Vulnerable groups such as seniors receive special attention. Cuba put a cohesive plan into motion that provides citizens with straightforward information, mobilizes workers to protect themselves and the country, and shifts production to necessary supplies.

At the same time, Donald Trump precautioned Americans to be wary of “fake news” about the virus. Then he said, “It will go away.” On February 26, he falsely said the number of U.S. COVID-19 cases “within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero.” He claimed, “It’s going to disappear thanks to what I did…” Then he told everyone they should go to church on Easter Sunday and that Americans should go to work even if they had the virus. Unquestionably, Trump’s behavior contributed to the spreading of the disease. His statements were consistent with the desires of industry to resume business as usual.

While the United States produces a surplus of unnecessary junk, Cuba produces a surplus of health care professionals. Consequently, Cuba has 8.2 doctors per 1,000 people while the United States has 2.6 doctors per 1,000. While I was on a 2019 trip there, a recently graduated Cuban doctor told me that he only works about 20-25 hours per week. But during medical disasters, it could easily be 80-100 hours per week.

Education. Cuba has used mass education to effectively change behavior during epidemics. In 2003, Dr. Byron Barksdale pointed out how Cuba’s six-week program for AIDS patients was “certainly a longer time than is given to people in the United States who receive such a diagnosis. They may get about five minutes of education.” During dengue outbreaks, medical professionals who go to homes explain in detail why water must be drained or covered and what plants augment mosquito breeding.

The United States confronts health crises with “campaigns” that are grossly inadequate. TV ads run for a few weeks or months, and physicians may receive brochures to give to patients. There is nothing even approaching visits to every home to inspect how families can be contributing to their own illness and how to adopt behaviors to counter the disease.

Donald Trump’s inconsistent rantings about COVID-19 are the epitome of miseducation campaigns. Climate denial has served as a dress rehearsal for COVID-19 denial. The Trump reign has been a practice session in stupefying millions into believing anything a Great Leader says no matter how ridiculous it is. His tweets have a pathological similarity to the intensely anti-intellectual perspective that is dismissive of education, philosophy, art, and literature and insists that scientific investigation should never be trusted.

The day before yesterday, they insisted that the world was flat. Yesterday, they believed that evolution was a theory from Satan. This morning, they insisted that heating of the globe is a fantasy designed to choke corporate expansion. How close must it get to midnight before those drunk with Trump’s Kool-Aid are willing to see the facts of COVID-19 growth unfolding before their eyes?

International Solidarity. Cuba made international headlines the third week in March 2020 when it allowed the British cruise ship MS Braemar to dock with COVID-19 patients aboard. It had been turned away by several other Caribbean countries, including Barbados and the Bahamas, which are both part of the British Commonwealth. There were over 1,000 passengers on board, mainly British, who had been stranded for over a week. Braemar crew members displayed a banner reading “I love you Cuba!” Undoubtedly, Cuban officials felt okay letting the ship dock because its doctors had gained so much experience being exposed to deadly viruses like Ebola while knowing how to protect themselves.

The same week in March, a medical brigade of 53 Cubans left to Lombardy, one of the worst hit areas of Italy, the European country most affected by COVID-19. Soon they were joined by 300 Chinese doctors. A smaller and poorer Caribbean nation was one of the few aiding a major European power. Cuba had also sent medical staff to Venezuela, Nicaragua, Suriname, Grenada, and Jamaica.

Meanwhile, the US administration was refusing to lift sanctions on Venezuela and Iran, sanctions that interfered with these countries receiving PPE, medical equipment, and drugs. Yet, it continued sending thousands of personnel to Europe for military maneuvers. It manufactured a smear campaign against President Maduro of Venezuela, portraying him as a drug trafficker. Trump disgraced America by pandering to his most racist supporters by referring to COVID-19 as the “China virus.”

As Cuba shared anti-virus technologies with other countries, reports surfaced that the Trump administration offered the German company CureVac $1 billion if it could find a remedy for COVID-19 and hand over exclusive rights “only for the USA.” This meant endangering the lives of Americans in two ways. By trying to monopolize a drug that had not yet been developed, Trump was trying to distract attention from the existing Interferon Alpha 2B which China was already including among thirty treatment drugs for the disease. By continuing the sixty-year-old blockade, Trump hampered Cuba from receiving supplies for the development of new anti-COVID-19 medications.

What Do Researchers Look For? When Cuban labs created Interferon Alpha 2B to treat dengue, it was just one of many drugs researched to investigate treatments, especially those that would help people in poor countries. Its use of Heberprot B to treat diabetes has reduced amputations by 80 percent.

Cuba is the only country to create an effective vaccine against type-B bacterial meningitis. It developed the first synthetic vaccine for Haemophilus influenza type B (Hib), as well as the vaccine Racotumomab against advanced lung cancer. Cuba’s second focus has been to manufacture drugs cheaply enough for poor counties to be able to afford them. Third, Cuba has sought to work cooperatively, with countries such as China, Venezuela, and Brazil, in drug development. Collaboration with Brazil resulted in meningitis vaccines at a cost of 95¢ rather than $15 to $20 per dose. Finally, Cuba teaches other countries to produce medications themselves, so they do not have to rely on purchasing them from rich countries.

In virtually every way, corporate research has been the opposite of that in Cuba. Big Pharma spends millions investigating male pattern baldness, restless legs, and erectile dysfunction because these could reap billions in profits. The COVID-19 pandemic promises to bring in super-profits, and governments are acting to make sure that happens. At the same time Trump was making promises to the German CureVac company, his administration was looking into giving exclusive status to Gilead Sciences for developing its drug remdesivir as a potential treatment for COVID-19. US taxpayers would dole out millions to create a medication that could be too expensive for them to buy.

Though Donald Trump is the nadir of national chauvinism countering global cooperation, it is important to remember that it is the market system that pushes research into investigations that yield the greatest profit instead of where it will do the most good.

Future pandemics. Cuba’s dengue epidemic in early 2012 seemed odd because outbreaks usually happen in the fall and are over by December. It is rare for them to last into January and February. Climate change is making local conditions more suitable for the mosquitoes that are vectors for dengue. During the last half-century, Cuban health officials have calculated a thirty-fold increase of the Aedes aegypti mosquito, the main vector.

Corporate media regularly tells us that COVID-19 is “unprecedented,” as if nothing like it will happen when it subsides because, after all, nothing like it has happened before. Not really. Claiming that COVID-19 is the “worst pandemic” to ever hit this continent is either saying that smallpox had no effect on Native Americans or that Native American deaths are irrelevant to medical history.

Years ago, when I first began investigating the need for degrowth, it seemed to me that health care could be the only area of the economy where some growth might be necessary to produce better lives, especially for poor people throughout the world. Though many comparisons show that European medical systems could cut costs by 30 to 40 percent in the US, Cuba demonstrates that resources usage could be reduced by as much as 95 percent while expanding aid to poor countries.

Part of this could be accomplished by reducing military used by rich countries to bully others into extracting raw materials for destructive growth. My book, Cuban Health Care: The Ongoing Revolution, details how decades of medical reorganization has allowed that country to accomplish so much by focusing on personal relationships as the foundation of good medicine.

Though creating tests, treatments, and vaccines are essential parts of fighting disease, they will not be sufficient in a society suffering from a pandemic of profit-gouging. The restructuring of society is critical not only to unleash the creative power to invent new things such as necessary medicines, but also to ensure those things benefit all who need them.

Teaser photo credit: By Roel Coutinho – Roel Coutinho Guinea-Bissau and Senegal Photographs (1973 – 1974), CC BY-SA 4.0