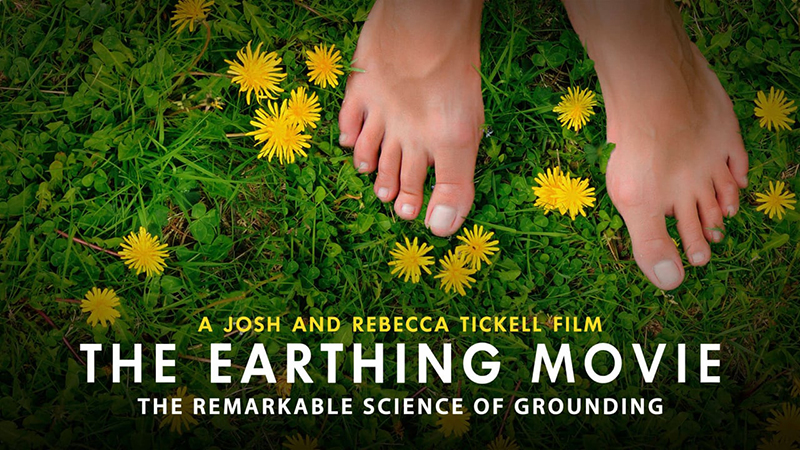

The Earthing Movie: The Remarkable Science of Grounding

Directed by Josh Tickell and Rebecca Tickell

Written by Josh Tickell

Narrated by Rebecca Tickell

Cinematographed by Simon Balderas and Jose Babcock

Edited by Ryan A. Nichols

Produced by Josh Tickell and Rebecca Tickell

Co-produced by Alexa Coughlin

Composed by Ryan Demaree

A Big Picture Ranch Production in Association with the Chopra Center, the Earthing Institute and HeartMD Institute

Release Date: Mar. 2019

Running time: 75 minutes

During the spring of 2010, while investigating the ecological and human health impacts of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill for their documentary The Bix Fix, filmmakers Josh and Rebecca Tickell were poisoned. For many miles around the spill site, the air was laden with a toxic mist made up of oil particles and the dispersant being sprayed on the oil to break it down. The Tickells interviewed Gulf Coast-area residents who had suffered respiratory illnesses, skin ulcers and other awful maladies due to the corrosive effects of the dispersant Corexit (a chemical banned in the United Kingdom but not in America). Josh came away with his health intact, but his wife wasn’t so lucky: Rebecca developed breathing problems, and the skin on her chest became so photosensitive she was told that from then on she’d have to keep it covered whenever she went outside. There was also a chance she might never bear children.

In the Tickells’ latest film, The Earthing Movie, Rebecca elatedly informs us that her health has returned and that she and Josh now have a healthy and happy young daughter named Athena. Every bit as jubilant as Fix was angry and bleak, Earthing tells the Tickells’ version of how Rebecca recovered her health—and how their daughter was cured of the torment that characterized her early life. They say these feats were accomplished through a form of nature therapy called earthing, also known as grounding. Earthing is founded on the premise that humans require direct skin contact with the surface of the Earth to maintain our bodies’ natural electrical state. Proponents of earthing claim that walking barefoot on grass, soil or any other natural surface for just 10 to 15 minutes a day can bring significant health benefits, including better sleep, reduced inflammation and improved heart rate. However, their evidence for these claims is unfortunately either anecdotal or based on flawed research.

Earthing begins with a montage and monologue in which Rebecca recounts how she and Josh first learned of the practice. They had decided, despite doctors’ warnings, to try having children. Their initial efforts were met with tragedy: a miscarriage followed by a baby girl with serious chronic health problems. Over the next two years, the Tickells found themselves in and out of hospitals as they desperately searched for a cure for Athena’s ailments. They had tried just about everything when a friend gave them a copy of the book Earthing: The Most Important Health Discovery Ever! It was written by former cable TV salesman Clinton Ober, cardiologist Stephen Sinatra and health writer Martin Zucker—with a foreword by James Oschman, an expert in electromedicine. Rebecca and Josh were skeptical at first but tried it anyway, whereupon Athena’s health underwent a miraculous reversal, as did Rebecca’s. Regardless of what caused their health to turn around, you have to be happy for them.

Ober is credited with the discovery of earthing. As he describes the series of experiences that he says first alerted him to the phenomenon, we get our first taste of this film’s decidedly anecdotal flavor. Ober grew up immersed in Native American culture, and one day the sister of a friend of his contracted scarlet fever. When conventional medicine had failed her, one of the elders placed her into a straw-lined pit, built a fire next to the pit and sat with her for days. She fully recovered. Another epiphany came when, as an adult, Ober spotted a crowd of people with a conspicuous, shared affinity for white Nikes disembarking from a tour bus. It suddenly occurred to him to wonder whether the advent of synthetic-soled shoes had caused people to lose their natural grounding.

This led Ober to what is by far the most extreme conclusion presented in Earthing: that the synthetic-soled shoe is “the most destructive invention that man ever made.” Ober says that by cutting us off from the Earth’s natural electric charge, modern-day shoes have contributed far more than any other factor to today’s prevalence of inflammation-related health disorders. In the film’s second-most-hyperbolic contention, he categorically asserts that when one is grounded, one doesn’t experience inflammation. Even granting this second premise, is it really possible to say that synthetic-soled shoes are our most deleterious invention? Seriously? I trust that if you, dear reader, were asked to enumerate humanity’s most destructive innovations, scores of other things would make their way onto the list before modern-day shoes did.

Celebrity endorsements are a classic marketing tool, and the Tickells aren’t above using them in their attempt to turn people on to earthing. It’s to this end that we spend some time with major league baseball player Matt Davidson, who has incorporated earthing into his pre-game routine. We also learn the story of actress and filmmaker Mariel Hemingway, who is the granddaughter of the great American author Ernest Hemingway. Ms. Hemingway describes herself as having come from “a very dysfunctional home,” for Ernest was just one in a line of relatives of hers who committed suicide after struggling with serious mental health issues. The woods, fields and mountains surrounding the Hemingways’ home were her haven from the alcohol-fueled volatility of her family life, and she discovered that lying down on the earth was especially therapeutic.

I could summarize plenty of other anecdotes, but I’m sure you get the idea. The trouble with anecdotal proof, of course, is that it’s a form of cherry picking. Earthing regales us with success stories but doesn’t mention failures—of which one would expect to find quite a number in any sample large enough to yield useful data.

There is one spot where the film manages to acquire at least a veneer of scientific rigor. It’s a scene in which Rebecca and Josh reenact poring over a collection of scientific reports. At a dining room table covered with neatly arranged copies of journal papers, the two of them focus on one particular study looking at the beneficial effects of grounding on vagal tone in preterm infants. Yet not one word is said about this study’s methodology. This is perhaps by design, given the damning criticisms that have been levelled against studies on earthing, namely that they’ve been small and poorly run.

One of the most dismal moments in Earthing comes just when it seems like the film is about to get beyond personal accounts and provide some data—but then doesn’t. Following a string of glowing testimonials, Rebecca poses the question of whether earthing really is the causative agent of the miracles that have been ascribed to it, or whether some placebo effect is at work. But instead of then turning to concrete proof, the film simply delivers another beaming testimonial, at the end of which the person giving it states, “I just have a hard time believing this is a placebo effect.” The individual in question certainly has impressive credentials: He’s a senior research medical scientist and a former U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) biostatistician. But what impresses even more is the failure of critical thinking it takes to accept that one person’s blind assurances can be an adequate substitute for a control group.

Another concerning thing about this movie is the controversy surrounding one of its experts, Dr. Joseph Mercola. Mercola is a physician and alternative medicine advocate who markets and sells dietary supplements and medical devices online. I looked up his Wikipedia entry after watching this film and was amazed to learn of all the ways in which he has run afoul of the FDA, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and many others. In 2011, the American Academy of Pediatrics demanded that an anti-vaccine ad partially funded by Mercola be removed from Times Square. In 2016, the FTC complained that Mercola had falsely advertised his line of indoor tanning beds, and Mercola subsequently agreed to pay a settlement of up to $5.3 million. Mercola has also received four warning letters from the FDA for breaking various laws in the testing, marketing and labeling of his products. Did the filmmakers not do their homework on this guy, or were they banking on viewers not bothering to Google him?

The Tickells seem resigned to the fact that their documentary stands little chance of swaying the minds of determined skeptics. Indeed, they repeatedly urge viewers to try earthing for themselves rather than taking the word of any of the experts or practitioners featured in the film. Yet there’s a fundamental flaw in this strategy. Suppose a certain number of open-minded viewers do heed the filmmakers’ entreaty for them to give earthing a try, and immediately thereafter experience improved health. Since the Tickells have failed to rule out the possibility of a placebo effect, how are these individuals to trust that their increased well-being really is the result of having undergone earthing, as opposed to their desire to be convinced that earthing is for real?

It’s well established that immersion in nature has a wide range of human health benefits. When we find ourselves in physical environments that are pleasing to us—as natural settings innately tend to be—our stress levels decrease, resulting in a host of positive knock-on effects for our nervous, endocrine and immune systems. Time spent in nature has also been found to boost our sense of connection to one another and the world at large. And of course, being outdoors encourages physical activity. How many people have enjoyed these and other incalculable rewards of being in touch with nature and mistaken them for vindication of earthing’s legitimacy?

Though nothing in this documentary persuades me that earthing is to thank for Rebecca’s and Athena’s health transformations, I’m certainly glad they’re flourishing. My hope going forward is that, along with physical sickness, the desire to bestow half-baked encomiums on unproven medical treatments has also been flushed from Rebecca Tickell’s system. She and Josh are capable of great work (with The Big Fix being perhaps their most impressive film so far) and with luck their next project will be a return to form.