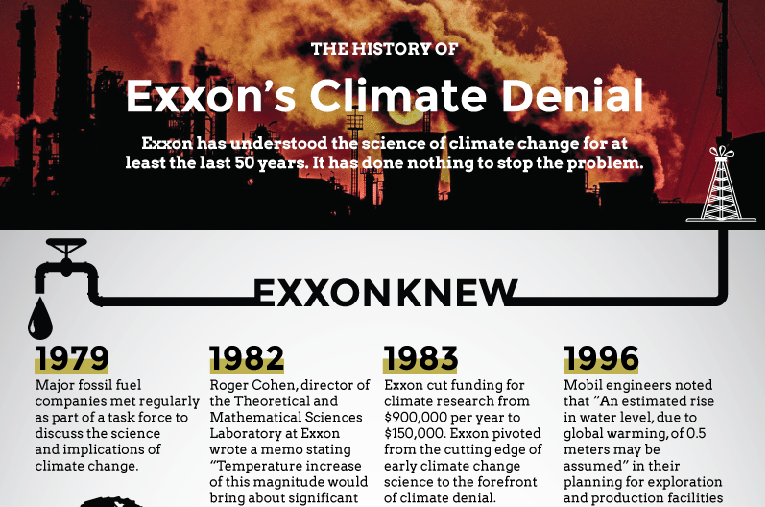

This month in a Manhattan courthouse, New York State’s attorney general Letitia James argued that ExxonMobil should be held accountable for layers of lies about climate change. It’s a landmark moment—one of the first times that Big Oil is having to answer for its actions—and James deserves great credit for bringing it to trial. But it comes with a deep irony: Under the relevant New York statutes, the only people that New York can legally identify as victims are investors in the company’s stock.

It is true that Exxon should not have misled its investors—lying is wrong, and that former CEO Rex Tillerson had to invent a fake email persona as part of the scheme (we see you, “Wayne Tracker”) helps drive home the messiness. But let’s be clear: On the spectrum of human beings who are and will be hit by the climate crisis, Exxon investors are not near the top of the list.

In fact, if the “justice system” delivered justice, the payouts for Exxon’s perfidy would go to entirely different people, because the iron law of climate is, the less you did to cause it, the more you’ll suffer.

The right set of priorities might put different groups of people at the front of the line for payouts: dwellers along the edge of the African deserts that are expanding fast as climate warms, Bangladeshi peasant farmers losing their land as the Bay of Bengal spreads inland, and Inuit hunters no longer able to depend on the sea ice. Every one of these groups was directly harmed by the decision of the fossil fuel industry to bury its knowledge of climate change in the 1980s and instead work to deny, deflect, and delay action.

When the CEO of Exxon told Chinese leaders in 1997 that the Earth was cooling and that it didn’t matter when they took action on climate change, the direct and indirect harm fell on South Pacific islanders now having to plan for the evacuation of their nations and South American cities losing their sole source of drinking water as glaciers disappear.

Even in the U.S., the burden falls disproportionately and violently on the most vulnerable communities—poor people and people of color. Wander into any disaster zone, from Hurricanes Katrina and Harvey to the California fires, and you’ll find that the hardest-hit people are the ones set up by the status quo with the least. Hurricane Sandy shut down Wall Street for a few days, but for working class and subway-dependent communities in the Rockaways and throughout Brooklyn and Queens, it changed lives forever.

Put another way, those who made their money peddling fossil fuels—the executives and shareholders holding funds—owe something to those who got hurt. It’s not, in the bigger picture, all that different from the demand for reparations by African American descendants of slaves—claims that in recent months more than a few institutions have begun to pay, among a growing number of faith denominations, universities and politicians, including presidential candidates, have begun to publicly endorse.

That’s not to say that fossil fuel extraction is a crime of the same kind as owning human beings. It isn’t—but the two are not unrelated; the same instinct to abuse and extract, deplete, discard, and disavow holds. And we have always understood the evil of slavery, but until about 40 years ago, as newly developed supercomputers made climate modeling possible, it wasn’t even clear that fossil fuel extraction and use carried with it a systemic danger. And where a wide variety of thinking offers plans for a real possibility of compensation for the victims of the transatlantic slave trade, there’s no practical way to compensate everyone who will be harmed by climate change.

Indeed, the high-end estimate for economic damage from the global warming we’re on track to cause is $551 trillion, which is more money than exists on planet Earth. Even that figure is notional: How do you compensate the generations of people yet unborn who will inherit a badly degraded world? Even if Exxon et al were to disgorge every dirty penny they’d ever made, it wouldn’t pay for relocating Miami, much less Mumbai.

We obviously should expand the circle of obligation. Even as we write, investment banks continue to bet against our survival and lend huge sums to this industry to expand its network of pipelines and wells. And they do this over the calls for a new economy and the end of the age of fossil fuels. At this point, JPMorgan Chase and Citi are the functional arms of Chevron and Shell. They literally make fossil fuel investments possible. But even holding them to the reckoning they deserve—though we will certainly try to do it—can’t bring back sea ice to the Arctic or compensate the fishermen around the world now watching their harvests shrink in a hot and acidic ocean.

The staggering cost of inaction here demands that we co-create the solutions with a concentric circle of communities that were made vulnerable to the effects of climate change. And that starts with thinking together about aligning these movements for “climate reparations” as a necessary framework for thinking about how we move forward.

Justice demands real money moving from the global North to the global South to compensate for the damage we’ve done. The United States has poured more carbon into the atmosphere than any other nation historically, and we’re champs when you measure it per capita, too. So it’s particularly painful that the Trump administration has stopped funding even the modest payments envisioned under the Paris accords.

And as we think about our own country and its efforts to deal with the climate crisis, we need to hold onto equity and justice as our guide. The communities that deserve priority in public spending are those that have suffered the most. It is a sadness to lose a second home on the Carolina coast or in California wine country, but it is a life-destroying tragedy when poor communities go underwater. Priority for the good jobs in a new energy economy belong to those whose communities suffered most from in the dirty energy era. The images from the Superdome in New Orleans during Katrina should haunt Americans as long as the climate crisis lasts. At its start, it was clear who the first and worst victims were going to be.

Framing the climate crisis as a matter of equity and another opportunity for justice doesn’t mean we stop thinking about it in other ways, too. In the end, this is a tussle with chemistry and physics, and clearly the most urgent goal is to slow down the planet’s heating. Building solar panels and wind turbines in the end ultimately benefits the most vulnerable. If the Marshall Islands have a chance at surviving, if the rice farmers of the Mekong Delta have any prayer of passing on their land to their sons and daughters, then it depends on a rapid energy transition for the whole planet.

But at this point, even the best-case scenarios are relentlessly grim; lots of damage has been done, and far more is in the offing. We’re going to have to remake much of the world to have a chance at survival. And if we’re going to try, then that repair job shouldn’t repeat the imbalances of power and wealth that mark our current planet. Justice demands a real effort to make the last, first this time around.