In the mid-1990s, the daily news headlines in the Southwest featured political gridlock, anti-government fanaticism, Us vs. Them tribalism, political assaults on environmental regulations, local demands to turn over federal land to the states, ‘patriotic’ armed militia groups, corporate attempts to commercialize our national parks, courtroom brawls between urban activists and rural residents over endangered species, and a bunch of finger-pointing and trash-talking generally.

That sounds likes recent headlines!

In fact, the 2014 standoff between rancher Cliven Bundy and federal agents over his grazing permits on public land as well as the armed seizure of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon in early 2016 by his sons and their comrades was disturbingly reminiscent of the “War on the West” rhetoric leveled at the Clinton Administration by “wise use” advocates twenty years earlier.

In 1995, rancher and Nye County (Nevada) commissioner Dick Carver made the cover of Time magazine under the title ‘Don’t Tread On Me.’ On July 4th, 1994, Carver illegally drove a D-7 bulldozer into a proposed wilderness study area to protest what he considered to be intrusion by the Clinton Administration into the daily life of county residents. The Time story proclaimed him to be a leader of the “rebellion now sweeping the West.” (see)

The story was repeated in May 2001 – except the “War on the West” culprit this time was the Bush Administration! (see).

It is often said that history doesn’t repeat itself – it rhymes instead. The first significant attempt by Congress to transfer federal land to the states began way back in 1947. Fortunately, a crusading, bespectacled columnist for the Saturday Evening Post by the name of Bernard DeVoto foiled this back-door plan. The second run at a western land grab, dubbed the Sagebrush Rebellion, rose in the 1970s as push-back by rural residents against wilderness protection on public lands.

The rebellion cooled considerably with the election of Ronald Reagan but flared brightly again in 1992 with the arrival of Bruce Babbitt, President Clinton’s Interior Secretary, to Washington with his “environmentalist” agenda.

The up-and-down, ebb-and-flow of this “rebellion” continued under the Bush and Obama Administrations. However, in recent years, polarization, conflict, trash-talking, and gridlock have expanded. It all took an ugly turn with the Bundy protests:

If problems are cyclical so are solutions. In an attempt to resolve the long-standing feud between ranchers and environmentalists, a small group of us decided in the late 1990s to find a ‘third way’ beyond the polarization. Our goal was to implement practical, on-the-ground goals through collaboration, not confrontation.

We called it the radical center and defined its mission as “a grassroots coming-together of diverse people to discuss their common interests rather than argue their differences and who agree to work cooperatively on a pragmatic program of action that improves the well-being of all living things.”

Bill McDonald, a rancher in southern Arizona, coined the term to describe an emerging consensus-based approach to land management challenges in the region. The unending feuds had resulted in gridlock where it mattered most – on the ground. Very little progress was being made on necessary projects, returning beneficial fire to natural landscapes, improving the chances of endangered species on private land, or helping ranchers fend off the rapacious interests of real estate developers.

Instead, it became a war of attrition with the only real winners being those who had no interest in the long-term health of the region.

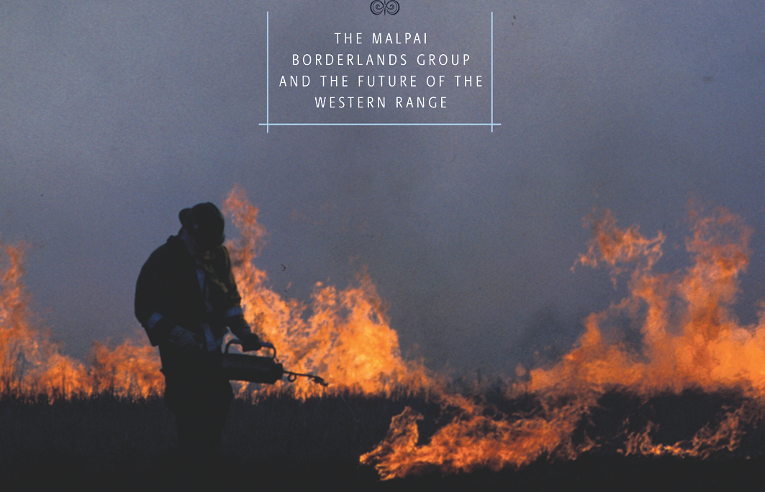

The radical center was a deliberate push-back against this gridlock. It was radical (which means “root”) because it challenged various orthodoxies at work at the time, including the belief that conservation and ranching were part of a ‘zero sum’ game. The center referred to the pragmatic, middle-ground between extremes. Together, they meant partnerships, respect, and trust. But most of all, they meant action – a plan signed, a prescribed fire lit, a workshop held, a hand shook. Words were nice, but working in the radical center meant walking the talk.

It worked. Over the ensuing years, the attitude toward ranchers and livestock among a cross-section of the American public, including lawmakers, opinion leaders, newspaper letter-writers and many conservationists, shifted substantially toward the positive. As a result, the so-called ‘grazing wars’ largely faded from view.

Soon, there were signs of progress all over the West as people worked together toward common goals. Especially encouraging has been the rise of watershed-based collaborative organizations across the region, many of them nonprofits. Cooperation became the norm – not the exception as it was when I began my work in conservation. Here’s a photo from an early Quivira workshop:

Can the radical center still hold? I hope so. The threats to land and people are bigger and more complex today, including climate change, a deepening divide between urban and rural populations, widespread damage by oil-and-gas production, and the undoing of important environmental regulations by the current Administration.

Counterbalancing these trends are ongoing collaborative efforts and the goodwill and respect that has been built up as a result of this work among diverse people and organizations.

To get through this turn of the wheel, however, we need the radical center more than ever. And not just on-the-ground. We need policies and economic incentives at state and federal levels that reward collaborative conservation and regenerative agriculture. Restoration of damaged and degraded lands, for example, is not only essential it can be very nonpartisan. Historically, communities came together to build a barn for a family. We can do that with the common ground below our feet as well.

That’s what Terra Firma is all about: looking at the world in a positive way, grounded in nature, experience, facts, and hope.

Resources:

- Here’s a very good history of the rise of the radical center: Working Wilderness: the Malpai Borderlands Group Story and the Future of the Western Range by Nathan Sayre, 2006. https://rionuevo.com/product/

working-wilderness-malpai- borderland-group/

- In 2003, twenty ranchers, environmentalists, and scientists wrote a declaration titled ‘An Invitation to Join the Radical Center’ that had a big impact in the West: http://jcourtneywhite.com/wp-

content/uploads/2016/09/ Radical_Center.pdf

- I’ve published the columns that I wrote during my Sierra Club and early Quivira years in a book titled Grassroots: the Rise of the Radical Center and The Next West, http://jcourtneywhite.com/

nonfiction/

- Here’s a new book by Gary Nabhan (who signed the RC declaration) called Food from the Radical Center (2018), https://islandpress.org/books/

food-radical-center

Video:

- Here’s a 3-minute primer on the Sagebrush Rebellion by the New Mexico Wildlife Federation (see).

- Here’s an 8-minute primer on American public lands and the conflict with state’s rights (see).

Ed. note: This piece is taken from Courtney’s weekly newsletter. You can subscribe to it here.