They say that your syntax always finds you out. Metaphors can be just as revealing. As George Lakoff observes, metaphors are the devices we use to frame the way we think about the world. In politics, according to Lakoff, it the competition for the frames–effectively, competition between the metaphors–that resolves electoral and political competition.

Tax, for example, is harder to raise when it is a “burden” and not an “investment in the common good”.

Cameron’s view on austerity, according to his memoirs, is that he and his Chancellor, George Osborne, should have cut deeper and cut faster when they came to power. Here’s the extract from the book, quoted in Politics Home:

My assessment now is that we probably didn’t cut enough.

We could have done more, even more quickly, as smaller countries like Ireland had done, to get Britain back in the black and then get the economy moving. Those who were opposed to austerity were going to be opposed — and pretty hysterically — to whatever we did.

Given all the hype and hostility, and yes, sometimes hatred, we might as well have ripped the plaster off with more cuts early on. We were taking the flak for them anyway. We should have taken advantage of the window of public support for cuts when it was open.

(My emphasis). I haven’t read the book, but this line from it has been widely quoted, from The Times to the Telegraph to the Independent to the New Yorker. Plasters, for American readers, are Band-Aids.

Counter-productive

This suggests that, whatever he’s been doing in his expensive faux-shepherd’s hut, he hasn’t been keeping up with the recent economics research. The International Monetary Fund, not normally regarded as a hotbed of radical thought, has concluded that austerity was counter-productive (pdf). The stated intention of the policy was to reduce debt to free up productive capital that was being “crowded out” by public spending (spot the metaphor).

But even on its own terms, this is wrong. The IMF research found that public sector cuts shrink the private sector faster than the public sector. If we’re doing metaphors, it turns out that the public and private sectors are co-dependent species. One of the associated mysteries to this is why George Osborne thought for a moment that he might be a suitable successor to the IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde.

Austerity and UKIP

Nor has Cameron been catching up on his politics research. Research at Warwick University published on the LSE blog found that exposure to austerity had a significant effect of UKIP’s share of vote in the years running up the referendum decision. It was of course, the share of UKIP vote that spooked Cameron into calling the referendum:

Estimates indicate that, in districts that received the average austerity shock, UKIP vote shares were on average 3.6 percentage points higher in the 2014 European elections and 11.6 percentage points higher in the most recent local elections prior to the referendum, compared to districts with little exposure to austerity.

The impact of austerity is estimated by the research as having increased the Leave vote by 9 percentage points.

On the High Street

The third thing he hasn’t been doing is getting out much, or getting out beyond the pleasant crescents of Notting Hill and the tree-lined avenues of Witney. Because the other effect of austerity has been to wreak havoc on the High Street. The conventional wisdom is that this is the result of online shopping, and obviously online has had an effect.

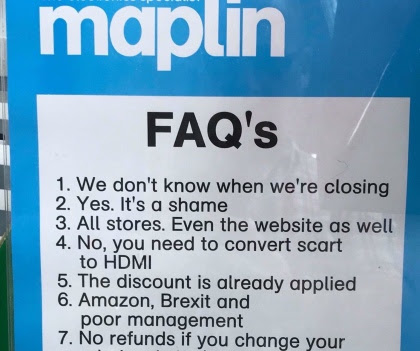

But austerity, with the flatlining household income and economic growth it caused, has had a bigger impact–and this on top of the online effect, happening anyway. The sums: analysis of data from the Office of Budget Responsibility by the New Economics Foundation suggests that the impact of austerity in 2018-19 alone to the overall economy is £100 billion, or £3,600 per household. Retail has high fixed costs, and small downturns in income can tip it over the edge into being unprofitable. This doesn’t just matter if, say, you used to work for Maplin. It matters because a thriving high street is a public good that extends well beyond shopping.

In short, Cameron has had a decade to think about this, and two years since resigning as an MP to think about nothing else. His conclusion: austerity, which as it was wrecked his economy and his Referendum, should have been pursued even more vigorously. It is the conclusion of a fool, or a zealot.

Empty metaphors

Here is the metaphor again:

‘we might as well have ripped the plaster off with more cuts early on’

As a metaphor it sounds good, at first hearing. It is tough, dynamic, and decisive, etc. But as a figure of speech, it is also completely empty. In one line we have an accurate summary of David Cameron’s Prime Ministerial career, maybe his whole political career.

So what’s the metaphor about? Well, that’s the problem. Let’s walk it back through.

Plasters go on cuts to help them heal. You take them off after the cuts have healed. How you take them off is a tactical decision: do you go quick, and a brief moment of pain when the hairs are pulled up? (This may also be a male metaphor). Do you go slow, and ease it loose? The strategy is about the healing. The skin has had time to knit itself back together over the cut.

So when Cameron says he should have ripped the plaster off more quickly, the question is, what is the plaster being ripped off from. Of course, “cuts”–by government–are a metaphor too. So maybe this discussion of plasters is actually the return of the repressed.

In other words, the entire metaphor is empty. If he’d been being honest, he’d have been talking about amputation instead, As I said at the beginning, your metaphors find you out.

Tactics and strategy

Of course, Cameron and Osborne were obsessed with tactics, constantly mistaking them for strategy. This led them to the process where their reputations have been trashed by the outcomes of their politics.

Anthony Barnett’s assessment, in his Brexit book, The Lure of Greatness, was succinct. “Cameron is one of those politicians who enjoys unlimited personal ambition untroubled by the burden of larger purpose.”

Falling stock

In the intervening couple of years, Cameron’s stock has fallen. The assessment this week of David Cameron’s career by Ian Dunt, on politics.co.uk, is brutal:

Cameron promised to match Labour spending, until he didn’t think it beneficial and turned fiscal hawk. He promised to get the Tory party to stop “banging on” about Europe, until that wasn’t useful either and he announced a referendum. He was green until he wasn’t. He was liberal except not really. He was relaxed about immigration but against it. He loved multiculturalism but insisted it had failed. There was simply nothing there. None of it meant anything. He was a tactic where a strategy should be.

We’re all still paying for the price for this, literally and metaphorically. And Cameron? He’s still doing empty soundbites.