The third anniversary of the Water Protectors movement at Standing Rock passed by quietly earlier this month. With the pipeline construction industry booming across the U.S. and Canada, Donald Trump seeking to bulldoze the cancelled Keystone XL Pipeline through more than 800 miles of unceded Lakota treaty territory, and at least nine state governments working to criminalize protest movements like Standing Rock, it seems that there is little to celebrate. We caught up with Lakota Spiritual Activist Cheryl Angel, an occupant and prior spokesperson of Sacred Stone Camp, to get her perspectives on the movement and what has followed, and to learn more about her upcoming women’s gathering in the sacred and besieged Black Hills of South Dakota.

This is the first in a series of collaborations with Grandmother Cheryl, whose travels and insights provide a refreshing, original and powerful counterpoint to the prevailing discourse on everything from economics to immigration to gender roles. When a Lakota woman speaks, it’s a good time to listen.

Esperanza: Can you start by telling us a little bit about your background before your activism days, and what led you to become involved in the Standing Rock issue?

Cheryl: Let’s see — where do I begin? Well, before Standing Rock I learned how to become a pipeline fighter and worked to stop a pipeline — the Keystone XL — at the Rosebud Sioux Tribe’s Spiritual Camp named Sicangu Wicoti Iyuksa, located near Ideal, South Dakota. And just before our camp was set up I began following Idle No More, and was excited to see our Northern relatives standing up to stop the tar sands and to protect their lands. So I guess I was slowly being prepped for Standing Rock.

However my background was being a parent for half my life and surviving on a reservation the other half. When you live on a reservation that has an imposed schooling system, living on a landbase originally serving as a prison area, while our treaty lands were ravaged by gold mining — and then later to have those treaty right ignored — you become actively aware of what is happening not only in your hometown and on the national level with Indigenous spokespeople holding the government to task, but also very aware that in the neighboring towns around us, racism is rampant.

As a parent I worked hard to keep my kids in school, safe, off drugs, and out of gangs – and I wasn’t as successful as I had hoped, and prayed, despite my intentions. My children suffered most of the same tragedies that a lot of our tribal children experience when they’re growing up under an imposed system designed to separate everything, starting with the taking of children out of the homes to go to school, a concept in direct opposition to our traditional teachings.

The removal of children into boarding school has left a dark wound upon our people, even in my own family. The boarding school era started so long ago, some kids today don’t know that their own ancestors were able to live free upon the prairie. This loss of knowledge is a shared tragedy of all our communities. The Boarding Schools… sad and heartbreaking. Yet our people, including myself, my mother and her mother, survived. Our traditions were meant to be to taught at home, and in the center of the circle in our communities. Right now I’m counting my blessings that my children are now grown and out of the dangerous age group that is most prone to die. It is an ongoing tragedy.

People don’t see a suicide or an overdose or a brutal killing or drug/alcohol related violence as a tragedy to the entire community. I see the tragedy. Why? Because the life of each member of each tribe is vital – we’re so small in the overall population, not even 1 percent of the entire nation – yet we have the traditions that were lived in our homes that were handed down generation to generation that held the teachings of everything needed to learn how to be a good person to yourself, to your family and to your community and nation. It’s a tragedy that now there’s not very many of us left to carry the message the Creator gave us to share on how to live with the animals and the plants of the land.

So we’ve adapted. We have to use the school system. We have to use whatever tools we have in front of us to make sure those teachings are being remembered, being taught and being practiced. And we have to remember how to live on the land without causing harm.

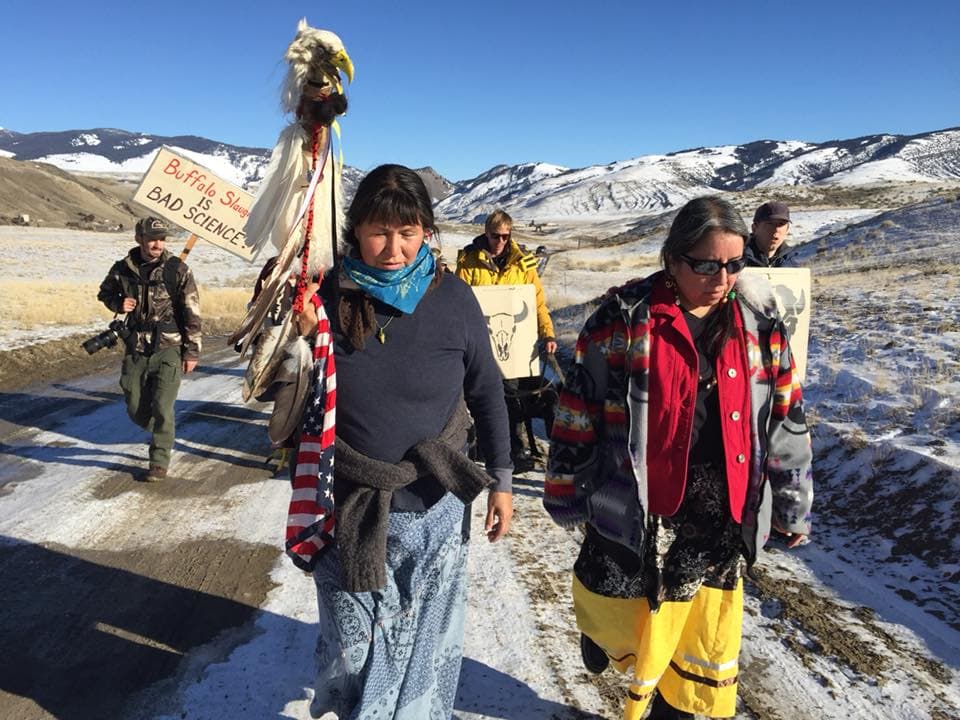

Image Credit: Rob Wilson photography

Esperanza: I suppose that must feel like a huge responsibility.

Cheryl: Yes, it is and again it isn’t. Once you stand up in resistance to the destruction of our Earth, our mother, there is no way you can sit back down. I’m positive I’ll be standing in solidarity aligned with all those who understand the threat to our water until the end. At this moment there are just too many multinational extractivist corporations to ignore. And with the current leaders in many countries, especially in my homelands, writing legislation to criminalize individuals and fast-track pipelines, now is the time for more people to stand up and fight for our next seven generations.

In the last couple of years I have met with original stewards and ceremony/wisdom keepers of many nations experiencing the real live threat of losing their water, their ancestral lands, and their traditional economies. And after being in ceremony with these elders and watching them, and seeing the wisdom they have, I understand what to do now. Deep inside we all know what to do. Stand Up Fight Back! But do it in a way that our ancestors would be proud of us. Our ancestors never went looking for a fight. We are defenders of the people, we are not troublemakers. You can see exactly what I’m talking about when you watch the video of an elder who also lived at Sacred Stone during the occupation of Standing Rock, Nathan Phillips, when he stepped into the chaos of two groups of individuals yelling at each other in Washington DC.

We were able to watch the video of what Nathan Phillips said in Washington D.C. He saw the verbal ruckus going on between two different church groups – one was really small less than 10 people, and then there were about 50 on the other side. He wanted to calm the waters, so to speak – and his story is common for most natives. We find ourselves in the middle of two struggling sides and we work to get them in a calm, peaceful state. But instead, we’re the ones who end up getting attacked in the middle.

This really happened in the Washington, D.C. march. A Catholic group of kids were wearing Make America Great Again red caps, and they were surrounding him and were mocking him, and weren’t letting him pass. They were jeering and making chopping motions.

What Nathan said was really crucial for many reasons. He said, we taught everybody in the community we lived in a long time ago how to live.

I agree with Nathan: HOW TO LIVE: We were taught how to recognize nature as a powerful, living source that we treated with respect; that’s where the animals lived; that’s where we got our sustenance from, that’s where we set up temporary homes – we were so careful not to leave a trace, that the next year we had to find the landmarks we left to remember where it was that we camped – because there were times we buried our dead along the trail and left landmarks for them. We’re still finding them today, those landmarks. Our relationship with the land is everything. How we live on those lands is everything we need to know. We were taught how to live in peace.

A student from Covington Catholic High School stands in front of Native American elder Nathan Phillips in Washington in this still image from a Jan. 18, 2019, video by Kaya Taitano. (Social media/Reuters)

I’ve always carried the old ways inside, in the words of my grandmothers – I was raised to always do the right thing for others — and even if I was reluctant, because I was the only one doing it, my grandma would say: Especially if you’re the only one who is doing the right thing, then you have to do it, or nobody will see what they should be doing. It doesn’t mean I’m perfect. It just means I think about what I do and say before I think about myself.

So my grandma, she was an activist because she believed in action. She believed in doing the right thing. She didn’t believe in just preaching. So I listened and I did what she told me. And I will never forget her words. I loved sharing the things I learned from the grandmas at the time when I was very little. I would dream of ways to bring back the old days and talk about making changes, and once my oldest told me, “you’re radical”. Hehehe, now those radical teachings are more important than ever. What’s so radical about opening our lands to the buffalo and taking down all the fences and letting the water run free? The buffalo were here long before we were here on these lands and we are the Pte Oyate because of an ancient covenant. Pte is the female buffalo and Tatanka is the male buffalo. Well, that’s what I was told, anyway.

Esperanza: So at what point did that find its way into activism for you?

Cheryl: Whenever the Oglala aquifer was threatened. When TransCanada started using eminent domain to get rights of way for the Keystone XL from landowners who weren’t fully aware of the effects that a pipeline spill would have on the land.

It was a lot of things. I’ve always been a radical thinker, but I never put my body on the front lines until Standing Rock. Activism really took ahold of me when I moved to Sicangu Wicoti Iyuksa; that’s when TransCanada started using eminent domain to create a pipeline on our treaty lands.

Sicangu Wicoti Iyuksa spiritual camp against the Keystone XL Pipeline, September 2014

Sicangu Wicoti Iyuksa spiritual camp against the Keystone XL Pipeline, September 2014

I don’t like using the word “first”, but our Tribe set up the Sicangu Wicoti Iyuksa spiritual camp on tribal land near Ideal, South Dakota, in March of 2014.

At the camp we were constantly researching all the material, and focusing on TransCanada’s history, the failures of their pipelines. We made alliances – at the camp I learned everything I could. I didn’t have any skills at that time except passion. (Laughter) And that’s all I needed.

I was filled with passionate love for the planet – I knew what TransCanada was doing was inherently wrong and went against everything I was raised to know about how to treat the land. So I felt a deep ache to be at the camp actively supporting in any way I could. I had to be there, because everything that I knew was at stake. Everything I was taught was in danger. That’s what it felt like. Like everything would be lost. So it was easy for me to go there.

Esperanza: So you were involved in the fight to stop the Keystone XL Pipeline. And then the leaders at Standing Rock contacted your leaders to ask for help.

Cheryl: Yes. At one of the hearings in Pierre, South Dakota, there was sign posted about the “Dakota Access Pipeline.” It was the first time I’d heard of the Dakota Access Pipeline. By that time the Rosebud Sioux Tribe had made alliances with Dakota Rural Action and Bold Nebraska. When everyone learned about the Dakota Access Pipeline it wasn’t long after that the leaders from the Standing Rock tribe contacted leaders from our tribe and asked how we set up our spiritual camp — in the end we were successful in using the camp to build alliances and together with those alliances Obama denied the KXL-TransCanada permit that the earlier George Bush administration had approved.

Or so we thought. Now the threat of KXL is looming in the horizon with our current leaders severely out of touch with their voters while ignoring all the disasters caused by climate change. They are failing to see what most 5th graders realize. Humanity has left a damaging legacy that is changing our climate and we must stop using fossil fuels and move forward with renewable energies and focus on supporting sustainable economies in our lives, including disciplining ourselves.

Esperanza: So you became involved with the Sacred Stone Camp, correct?

Cheryl: Yes, Sacred Stone was opened on April 1 – Joye Brown had her tipestola set up already when I arrived with my camp family from Sicangu Wicoti Iyuksa to support and assist in the “Run For Your Life” event, which was a relay run by native youth of the Oceti Sakowin from Cannonball, North Dakota, to Omaha, Nebraska, the headquarters of the Army Corps of Engineers. The youth carried with them not only the prayers of protection from the communities but also a petition to deny the permit of the DAPL: a petition signed by all the people who did not want the pipeline built.

Yes, it was the middle of the month of April. There were four of us, myself, my two sons, and my sister, Leota Eastman. We are all pipeline fighters and water protectors. Leota occupied both Spiritual Camps in Rosebud and Standing Rock. She was in the caravan of youth runners on the second Run For Your Life relay run to D.C. that carried the petition to deny the DAPL permit.

The first Run For Your Life relay from Sacred Stone Camp, three of us ran: Leota, my son Lance and me – to deliver a petition of signatures in opposition to the DAPL permit, to the district office of the Army Corps of Engineers. The second run was in July 2017, all the way to Washington, D.C., to the headquarters of the Army Corps of Engineers to deliver the petition… by that time it was signed by over 60,000 people.

Esperanza: Ah, so your kids came around then and changed their views?

Cheryl: Yes, they did. They used to say – “nobody thinks like you, Mom, you’re old-fashioned.” But they came around, yeah. (laughter)

I brought both my sons, Happy and Lance – Lance was the one who helped start the Rosebud Camp on the other side of the hill, right across from the Oceti Camp. My son Happy American Horse was really instrumental – he was the first to lock down one of those excavating machines. That was the first non-violent action.

Happy American Horse and other activists took non-violent direct action by locking themselves to construction equipment. August 31, 2016. (Photo: Desiree Kane, Wikimedia Commons)

Happy American Horse and other activists took non-violent direct action by locking themselves to construction equipment. August 31, 2016. (Photo: Desiree Kane, Wikimedia Commons)

At the Rosebud Camp, we had ceremonies out there. We had a welcome area where we gave out the information, we had them sign in, we told them what the plan was and invited them to join us, and had different roles they could choose – either they donated money or they donated supplies or they brought more people or they got on the network or they reached out to their allies… but everybody did something.

And that’s how Sacred Stone Camp got started too. The first time I went there it was to support the youth run. We got there at like 3 or 4 in the morning. A young KXL Pipeline fighter greeted us, and we were so happy to see him, because he was at every march and rally that we went to. He was wise, but very young. He was security. We parked on top of the hill where all the flags were at; later there’d be more flags.

The camp was small; there was only one tipi. Wiyaka, he was there, he’s also a pipeline fighter and water protect from the camp family from Sicangu Wicoti Iyuksa in Rosebud. As a matter of fact there are many many people from my Tribe who will never sit back down, after standing up. I’m really proud of all the Pipeline fighters and Water Protectors on the planet but especially proud of the ones who stood up to stop the pipelines first. Wiyaka stayed that first night when they opened the camp at Sacred Stone. That’s an honor no one else can share.

In July Sacred Stone had their second youth run, this time to carry the petition to Washington, D.C., and by the time they came back to Cannonball there were nearly 5,000 people coming to Sacred Stone with nowhere to camp. Shortly after that our Tribe, the Sicangu Oyate, set up camp — and that camp was filling up, too. And pretty soon everyone was sent to an flat area called the overflow area, A beautiful place — that’s where many, many smaller camps were set up and that area eventually became the Oceti Sakowin camp.

Running for their lives: Native American relay tradition revived by Native youth to protest Dakota Access Pipeline. (Salon/Social media)

Running for their lives: Native American relay tradition revived by Native youth to protest Dakota Access Pipeline. (Salon/Social media)

Esperanza: Can you share with me some of the lessons you learned at Standing Rock?

Cheryl: One lesson from Standing Rock that stands out for me is that without the support of mainstream media telling the truth about what was happening at Standing Rock – the truth behind why all the people were camped there – without their honest reporting as to the impact of these oil and gas and fracking pipelines to water, the people who will be affected won’t know the truth of how devastating pipelines are to watersheds and rivers and their water supply.

In my opinion, mainstream media failed the people of the country, not just the water protectors. They could have prevented all of the abuses of the law enforcement, the unnecessary jailing of hundreds, and no one would even have had to end up with trumped up criminal charges, if they had wanted to share the truth about pipelines. They didn’t care enough about the water quality of the Mni Sose or the people of Standing Rock. Mainstream media has not ever accurately reported the facts of what pipelines actually do to the environment, nor the truth about the governmental figures lending their political weight to approve illegal pipeline permits and how the banking system was funding the pipelines, even though it was very clear that the banks were not following the Equator Principal.

There were some news outlets that were very loyal, to not only our struggle but to struggles similar to ours in other communities – Democracy Now, I have to hand it to them. The Young Turks, Josh Fox; the Huffington Post, The Guardian, Unicorn Riot was on the spot, taking front line videos and sending those messages out – they themselves were jailed for reporting. Neil Young had a song he wrote and added an extra verse that included a statement about Standing Rock that included my son Happy. There were so many people coming I can’t even list all the people – those are just the ones that come to my mind first.

At the very end when the Standing Rock occupation was getting shut down, CBS came and some other people came but they had to sign waivers from the state of North Dakota.

“Right now we’re just pebbles. But when we march together, and we sit down and pray — we’re a rock.” Cheryl Angel, Nov. 27, 2016, Standing Rock. Video by Beth Pielert, goodfilmworks.com.

Another lesson I won’t forget is that even when you are right, it doesn’t necessarily change anything. Early on, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe filed in court saying that the permit was illegal, that was the legality for us holding those grounds – they were building a pipeline using an illegal permit, signed without tribal consent. We knew we were right, that’s why we stood as long as we did.

After the pipeline was built, when the case finally went to court, the judge said, ‘Yes, you’re right, the permit was illegal.’ Standing Rock knew that the permit didn’t abide by the guidelines — it didn’t have an environmental impact statement, and it didn’t have a statement on how it was going to impact the tribal culture, or those effects into the future.

The Judge also said that since the pipeline is already built I’m going to let the oil flow. Which doesn’t make any sense. The judge knew the Army Corps of Engineers approved the permit knowing full well that it didn’t meet the permit requirements and the oil should be stopped until the impact study is completed.

Winning in court didn’t stop the use of the pipeline and it should have. The DAPL permit was illegal, so the pipeline should be removed. Like I said —even when you win, it doesn’t always change things.

Esperanza: I know, that was very hard, and very unfair. I know it affected everyone who was there. After Standing Rock, what was your thinking about what you personally wanted to do next, with your own life?

Cheryl: Well, that’s just it. My own life isn’t my life anymore, because once you stand up and you see the injustice and you see the lack of concern for the environment from a corporate and legal standpoint, it doesn’t end that easily. Another thing, while you’re standing there you get to talk to the person standing next to you, and you get to hear their stories.

And they all came with stories – devastating stories about what happened because nobody stood up – or when they did stand up they were either killed or massacred or forced off the land. But at Standing Rock people weren’t going to lay down, because we knew we were right. The judge said we were right, even after the pipeline was built.

Now it makes perfect sense to protect water everywhere. I have a deep relationship with water. I know its alive. I know it can hear our pleas, and our songs and all the prayers said along its riverbanks and shores.

As Indigenous people with sovereign economies, we don’t have the need for a huge capitalistic society to come onto our lands and we certainly don’t need these pipelines destroying the water we need to drink.

So water is in danger, globally. Right now Indigenous communities are still at risk, and they are standing up, because they have to stand up. When you finally realize — WATER IS LIFE — you understand why you can’t sit back down.

People keep saying “after” Standing Rock – but I’m still of the same state of mind, I still have the same passion for the water, it has to be protected. It was when I was at Sicangu Wicoti Iyuksa that I learned about the aquifers that were in danger and when I was at Standing Rock I learned about the rivers that were in danger.

Cheryl Angel with Karen Little Thunder

Cheryl Angel with Karen Little Thunder

When I went to Mexico I learned that pipelines are coming down from Canada and then through the United States on down to Mexico. So this is a global issue. This encompasses the entire Americas – Turtle Island’s waters are in danger from the pipelines and the oil and gas and gold and silver and copper mining. So there isn’t an “after” Standing Rock for me. I’m still standing and so are the hundreds upon hundreds who understand what “Mni Wiconi” really means.

In my travels after Standing Rock I listened to stories about rivers and lakes that need to be defended from oil/gas and mining extraction – extractivism. These extractivism economies are all endangering the environment – and hold a huge responsibility for climate change.

So the power of making alliances with Bold Nebraska and many others, the power of telling the truthful consequences of what’s going to happen to the water when pipelines break – that’s what I work for. That’s my job. That’s my responsibility. That’s my future. I guess that’s my job description. I work toward the unity of people, the making of alliances. I know that building those alliances are the key to stopping extractivism from contaminating our waters.

What do I want to be called? Water Protector. Spiritual Activist. Unci. In reality, I’m just one person who stood up with thousands of others when the water called them. As one person I feel called on, at a very deep level, to connect with water. I go to ceremonies – especially water ceremonies. For centuries peoples all over the Earth have been doing that because a reverence for water is what’s needed. And that’s what the world’s leaders fail to see.

I go to urban places and I talk to the landowners – because the places I go the people own their houses, they own their land – and I say, ‘It’s time you stand up to protect your watershed.’ If everybody stood up and protected their own land, and their own watershed – if they remembered what it used to be called, if they remember the river and what the natives used to call it, if they called natives to have ceremonies on these lands where the watersheds are, we would be more in balance than we are today. We would be on the right path to reconciliation and a movement of unification of people who lived on the lands

So I’m really working hard to unite people because of the need to protect the water. I really do believe if people could protect their own watershed – if they could learn the name of the people who used to be the guardians of that watershed, if they could invite those people back onto those lands to have their ceremonies again for the water – that would be building an alliance, that would be holding the water in reverence, that would protect the water and could start to heal the people who have been separated for too long. I also call upon land owners to return their lands to the tribal nations that were forcefully removed from their ancestral homelands, the places where they lived in peace and were getting along by practicing their sovereign economies.

Esperanza: That would be a beautiful thing. And do you see that happening?

Cheryl: I do! It is happening. I have a friend – I was going on this tour to talk about watersheds and talk about people returning their lands to their tribes – and she has a big piece of land and she said, I’m not going to give away my land to the Tribe (laughing). So I felt obliged to correct myself and say, “For people who really feel it in their hearts that the land belongs to the native people and especially if it’s where they have ceremonies, that they give them back a piece of their land so they can freely come back and have ceremonies as needed.”

Just this past year Art Tanderup and his wife Helen out of Neligh, Nebraska, gave land to the Ponca tribe. That’s where the “Harvest the Hope” concert was held. Neil Young and Willie Nelson had a concert to support the resistance movement to stop the Keystone XL Pipeline.

Esperanza: Oh, yes! I remember reading about that!

Cheryl: See? So people are listening (laughing). And my friend — eventually she made a land deal so that her lands would eventually be turned back into Trust Status for the Tribes.

Esperanza: You’re right, it’s true. It’s beginning to happen.

Cheryl: Art and his wife Helen are the best people to listen to when it comes to being a land owners and pipeline fighters! We keep in touch and they are family to me.

Esperanza: That’s amazing!

Cheryl: Yes, it is amazing.

Next: Cheryl talks about economic sovereignty, the lessons learned in her travels in Mexico, and her upcoming gathering in the Black Hills, June 9-16.

This series is produced in collaboration with The Esperanza Project, a Green News Portal for the Americas.

Teaser photo credit: Ladonna Brave Bull Allard and Cheryl Angel make ceremony on the Back Water Bridge, Standing Rock November, 2016. Photo by Beth Pielert.