Ed. note: This paper was originally published in 2008.

Dr. Daniel Christian Wahl; Findhorn Foundation College, The Park, Findhorn, Forres IV36 3TZ; & Centre for the Study of Natural Design, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HT

Abstract:

Education for social and ecological literacy will be an important catalyst in the process of creating a culture of sustainability. The challenges of climate change, approaching peak oil, and non-renewable resource depletion are creating the need for an education that empowers citizens through knowledge and skills which enable them to actively participate in the design and creation of sustainable communities and bioregions. This paper will demonstrate how educational alliances between the Findhorn Foundation College, the Global Ecovillage Network, Gaia Education, Living Routes, and various universities in the UK and USA are beginning to address the urgent need for education for a sustainable future. The structure and content of the UNITAR endorsed Ecovillage Design Education (EDE) curriculum and the Findhorn Community Semester (FCS) will be reviewed. The EDE curriculum forms the basis of intensive training courses that are being offered on five continents as an official contribution to the United Nations Decade for Education for Sustainable Development (UNDESD 2005–2014). The global and local educational alliances explored in this paper link Scottish, UK, and international universities with non-governmental organizations, engaged citizens, educational charities, and sustainable community projects on five continents. The author will report on the progress of an attempt to create innovative new masters programmes in integrated sustainable community and ecovillage design through collaboration between the Findhorn Community College, Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE) Moray, and various Scottish universities and UK institutions. Some of the existing precedence for alliances between educational charities focussed on sustainable development and universities will be reviewed in this context.

Keywords: Education for Sustainable Development, Sustainable Community, Ecovillage Design Education, global — local alliance, ecological and social literacy

1) Social and Ecological Literacy: Enabling and Inspiring Community Participation

The shift towards a culture of sustainability will neither be a purely bottom-up nor a purely top-down process. In order for government frameworks, policies, and incentive programmes to take root in the private sector and civil society, widespread community participation will be required. Motivated and aware citizens need to be supported by appropriate policy frameworks to make sustainable consumer choices economically possible, just as government incentive schemes require educated and aware citizens to implement sustainable practices at a community and neighbourhood scale.

A renewed sense of ecologically and socially responsible business and citizenry that is both globally and locally aware will have to emerge along side with inspired political leadership, if we are to respond in time to the interconnected challenges of climate change, resource depletion, and national and international inequity. Eco-social literacy as prerequisite for the emergence of a culture of sustainability puts education, communication, and the media into the crucial role of being the facilitator of the necessary changes in worldview and value systems, as well as, in technological and scientific awareness, which ultimately will lead to the profound changes in lifestyles, aspirations, and culture that will characterize the shift toward sustainability.

Education for social and ecological literacy needs to be aimed at all the stages of the life-long learning path — from the role of parents and community, primary and secondary education, to vocational training, apprenticeships and higher degrees, and on to continued professional development, and evening classes for adults of all ages. Socio-economic realities, local and global environmental conditions, the world we live in, are now changing at such a speed that the traditional three phases of life (education, work, retirement) cannot be so clearly separated anymore. New trends show a need for continued education throughout life and for flexible working arrangement extending beyond the retirement age.

Education for socio-ecological literacy, as the basis of education for sustainable development, is the single most promising catalyst for widespread participation in the sustainability transition. While the media also plays a crucial role in facilitating such education for a large proportion of the population, this paper will focus on the role of education in general and higher education in particular. Without increased socio-ecological literacy we cannot expect citizens, governments, and business to respond appropriately to the complex and interconnected challenges posed by the urgent need to transition into a culture of sustainability.

Prof. David Orr, one of the world’s foremost environmental educators and originator of the term ecological literacy, suggests that “an ecologically literate person would have at least a basic comprehension of ecology, human ecology, and the concept of sustainability, as well as the wherewithal to solve problems” (in Stone & Barlow, 2005, p.xi). Peter Buckley, co-founder of the Centre for Ecoliteracy in Berkeley, California believes that “at the heart, the ecological problems we face are problems of values. Children are born with a sense of wonder and affinity to nature. Properly cultivated, these values can mature into ecological literacy, and eventually into sustainable patterns of living (in Barlow, 2004, p.7).

Orr explains: “Real ecological literacy is radicalizing in that it forces us to reckon with the roots of our ailments, not just their symptoms” … this ultimately “leads to a revitalization and broadening of the concept of citizenship to include membership in a planet-wide community of human and living things” (Orr, 1992, p.88). The important role of education for sustainability and the need for increased social and ecological literacy as well as a more holistic approach to science has been pointed out by a number of authors (Orr, 1992; Goodwin, 2001; Capra, 2004; Wahl, 2005; Bower, 2001; O’ Sullivan, 1999; Sterling, 2001; and Wheeler et al., 2000).

In order to achieve the lasting effect of motivating an ecologically and socially literate citizenry and business to engage in activities within their local and regional communities that support a transition towards more sustainable practices and systems, education for sustainability has to be transformative. Such education has to provide citizens with the knowledge why a shift towards a culture of sustainability is an ecological and social imperative in order to avoid run-away climate change and the associated societal break down. Yet it has to go deeper than that, offering a profoundly transformative experience that raises awareness, shifts paradigms and worldviews, and changes value systems, thereby causing and sustaining a change in lifestyle.

Transformative education for sustainability has to inspire people with a hopeful vision of a better and more meaningful life, beyond purely material consumption. It has to facilitate the creation of a new vision that offers a higher quality of life and a more desirable future for individuals, their families, their communities, and humanity as an interdependent whole. In his insightful book Sustainable Education: Re-visioning Learning and Change, Stephen Sterling proposes:

“Instead of the ethos of manipulation, control, and dependence, the ecological paradigm emphasizes the value of capacity building and innovation, that is, facilitating and nurturing self-organization in the individual and community as a necessary basis for ‘systems health’ and sustainability” (Sterling, 2001, p.55).

Social and ecological literacy helps people to understand the basic “patterns that connect” (Capra, 2002) and thereby create individual, community, ecosystems, and planetary health as a basis for long-term resilience and health (Wahl, 2007). It enables citizens to take responsibility for their own effects on the locally, regionally and globally interconnected world we live in and become active co-creators of the emerging culture of sustainability. Sustainability challenges all of us to envision, design and create a sustainable future for all of humanity. Sustainability is less a fixed state that can be reached and maintained, and more a community-based process of learning how to participate appropriately in the complex social, ecological, cultural and economic dynamics that characterise the world of the 21st century.

2) Ecovillages: Community-Scale Classrooms and Experiments in Sustainability

In practice, the concept of the “ecological settlement” is a multi-facetted one, encompassing the qualitative improvements of open spaces, traffic limitations, new social relationships and forms of organisation, strategies of energy and water efficiency, building biology criteria, the recyclability of building materials, aesthetic qualities and new cost/benefit analyses. What unites all these aspects, however is that they strive for, and to varying degrees attain, an optimization of the whole, rather than a maximization of individual parts, and thus a new quality of housing and indeed life itself (Kennedy & Kennedy, 1997, p.221).

For over four decades ecovillages have provided living experiments in the creation of more sustainable communities. They are community scale laboratories of social and ecological invention (Dawson, 2006). Ecovillages are testing grounds for ecological and renewable energy based technologies, offering opportunities for the application of new and old methods for strengthening local and regional economies. Such intentional communities have developed and applied a wide range of socially useful ‘sustainability software’ which helps people to communicate more effectively and non-violently with each other, to make consensus-based decisions, and respond to the inevitability of conflict with creativity using tested methodologies of mediation and conflict facilitation.

As such, ecovillages provide an ideal context for education for social and ecological literacy and can be seen as living classrooms for the kind of transformative education that will help us in creating a culture of sustainability. Prof. Brian Goodwin, cofounder of the Santa Fe Institute for complexity theory and initiator of the MSc. in Holistic Science at Schumacher College believes: “What we need is an education for collective living rather than for individual success. The collective to which we need to pay more attention includes all the other species of this planet, as well as the such as whether that allow their survival” (Goodwin, 2001, p.41). Ecovillages provide an ideal context in which such education can take place.

Eco-social literacy can best be communicated by example and engaging the learner as a participant in the kind of interconnected eco-social network about which one would like to create increased awareness. Fritjof Capra argues that one of the keys to increasing ecological literacy in children and people of all ages is the opportunity to experience ecological relationships and community directly through a participatory approach to learning that allows for truly transformational learning to take place (Capra, 2004). Ecovillage communities as human-scale experiments in sustainable living provide an ideal context for such transformative education.

Since “living systems are nonlinear and rooted in patterns of relationships, understanding the principles of ecology requires a new way of seeing the world and of thinking — in terms of relationships, connectedness, and context” (Capra, 2005, p.21). According to Capra “the starting point of designing sustainable communities may be called principles of ecology, principles of sustainability, principles of community, or even the basic facts of life” (Capra, 2005, p.23).

Ecovillage based education programmes give their participants the opportunity to experience and pay attention to such community-based principles of sustainability within a participatory learning environment. Ultimately, Capra argues that ecological literacy makes us aware of nature’s “fundamental patterns of organization: nature sustains life by creating and nurturing communities” (Capra, 2005, p23).

Robert Gilman defined an ecovillages as “a human scale, full-featured settlement, in which human activities are harmlessly integrated into the natural world, in a way that is supportive of healthy human development, and can be continued into the indefinite future” (Gilman, 1991, p.7). Robert and Diane Gilman conducted an extensive worldwide study of intentional communities, and discovered that while no perfect single example of a fully sustainable ecovillage could be identified, the overall pattern of design principles that emerge when ecovillages on five continents are compared give an indication of what constitutes a truly sustainable community.

Recent studies investigating the ecological footprint of various ecovillage communities, the Findhorn Foundation in Scotland, Sieben Linden in Germany, and the Ecovillage at Ithaca in the United States all indicated that ecovillage residents have a significantly reduced environmental impact compared to the national average of the countries in which they are found.

An ecological footprint study jointly conducted by the Sustainable Development Research Centre (SDRC), the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), and the Findhorn Foundation (FF) investigated environmental impact of the FF ecovillage and its international guest programme. The study included the categories food, home, energy, transport, consumables, services, government and capital investment. The ecological footprint measure expresses the environmental impact of resources use and waste production in terms of global hectare (gha) of bioproductive planetary surface area needed to generate those resources and absorb the waste created.

The overall ecological footprint of the FF ecovillage and its guests was recorded as 2.56 gha per person. This figure is based on a weighted average between the footprint calculated for FF community residents (2.71 gha) and people on FF guest programmes (2.10 gha). By comparison, the UK per person average is 5.4 gha. The result is also significantly lower than the results obtained for the celebrated Beddington Zero Energy Development (BedZED) in London, which achieves a per person average of 3.2 gha (Tinseley & George, 2006, p.4).

Jonathan Dawson, president of the Global Ecovillage Network and resident of the Findhorn ecovillage, emphasized the ecological footprint study demonstrated “that it is possible to significantly reduce resource consumption while continuing to enjoy a high quality of life” (Dawson, 2007). John Barrett of the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) based at the University of York concluded: “SEI has now undertaken a footprint analysis of a number of communities across the UK and the Findhorn ecovillage has the lowest to date. We believe that everyone has something to learn from their low footprint lifestyles” (in Dawson, 2007).

Increasingly, ecovillages have recognised the important role they can play as centres for practical and theoretical centres of transformative learning. While many ecovillages have a long history of running personal development courses, during the last decade more and more ecovillages have established ‘living and learning centres’ with the support of the Global Ecovillage Network’ and have created successful programmes in education for sustainable development.

3) The Findhorn Community Semester & the Ecovillage Design Education Curriculum

The mission statement of the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN) reads as follows: “We are creating a sustainable future by identifying, assisting and coordinating the efforts of communities to acquire social, spiritual, economic, and ecological harmony. We encourage a culture of mutual acceptance and respect, solidarity, love, open communication, cross-cultural outreach, and education by example. We serve as a catalyst to bring the highest aspirations of humanity into a practical reality” (Jackson & Svensson, 2002, p.144). With the establishment of ‘Living and Learning Centres’ in ecovillages on five continents GEN took a more active role in education for sustainable development.

In 2001, the US American educational charity Living Routes (www.livingroutes.org) established a relationship with the University of Massachusetts in order to be able to offer officially accredited undergraduate semesters programmes taught at international ecovillages to North American college students. One of their longest running programmes is the Findhorn Community Semester (FCS) offered under the title “The Human Challenge of Sustainability.” This programme is delivered in collaboration with the Findhorn Foundation College (www.findhorncollege,org), and brings between 10 and 18 students to the Findhorn Foundation ecovillage for three-month-long spring and autumn semesters each year.

Most of the feedback the Findhorn Foundation College receives from its students describes their educational experience as “life changing”, “eye-opening”, and “deeply inspiring and empowering.” In a recent article in Communities Magazine, former FCS student Sarah Steinberg explains: “I returned home feeling empowered to make a serious contribution to my college town. … my senior project this year is to establish a local currency in the town.” She emphasizes how deeply she appreciated that all her classes at Findhorn were experiential and how she came to see ecovillages not simply as “little bubbles of peace and sustainability” but as “laboratories for social, environmental, and technological experiments.” Sarah concludes: “At Findhorn… the whole community is a wonderful classroom” (Steinberg, 2007).

The Findhorn Community Semester is structured into four modules, entitled ‘Applied Sustainability’, ‘Exploring Sustainable Living through Creative Expression’, ‘Group Dynamics and Conflict Resolutions’, and ‘Worldviews and Consciousness.’ The students are not only taught theory but also engage practically in a transformative educational process that involves the entirety of their being. They take part in the daily life of the ecovillage, sharing work shifts in the gardens, maintenance, the kitchen, or homecare with the other residents and guests of the community. The college offers education for heads, hands, and hearts.

The curriculum was developed based on many years of experience in running personal development courses at the Findhorn Foundation. It takes a holistic approach to the challenges of sustainability that also formed the basis for the development of the ecovillage at the Findhorn Foundation. The structural engineer John Talbot, co-initiator of the ecovillage project, distinguished four aspects of the transition towards a culture of sustainability, which are listed below (in Hollick & Connelly, 1998).

- Ecological Sustainability: Sustainable physical systems and structures that are integrated into the existing natural environment around us. Each microcosm or system is self-sustaining within itself but interdependent and inter-connected with a larger macrocosm of the whole.

- Economic Sustainability: Small scale business, crafts, and services that create maximum diversity of the economic base and a rich ecology of financial, income and job opportunities.

- Cultural Sustainability: Satisfying our need as human beings to be creative and expressive; to learn, grow, teach and be; to have a diverse, interesting, stimulating and exciting social environment and range of experiences available.

- Spiritual Sustainability: Our relationship to the larger context of life and the Greater Reality of which we are a part: the spiritual dimension of our own divinity; Gaia and the planetary system; our greater purpose for being here now, our real connection to all of life.

These principles and the work of the Findhorn Foundation College and Living Routes have strongly influenced the development of the Ecovillage Design Education curriculum which has been undertaken since 2002 by an international consortium of ecovillage educators supported by the Global Ecovillage Network. Gaia Education, the educational arm of the GEN, launched this new curriculum at an international conference in Findhorn in October 2005 with the endorsement of UNITAR (see www.gaiaeducation.org). The first EDE pilot programmes were held in 2006, and by the end of 2007 ecovillage design programmes will have been taught to more than 500 participants in Scotland, Mexico, Brazil, Israel, Portugal, Germany, Sri Lanka, Australia, Turkey, the USA, Thailand, and India. These EDE programmes are an official contribution to the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development 2005 -2014 (see UNESCO, 2007).

All of the Findhorn-based courses on sustainability, including the EDE and the FCS, go beyond the commonly quoted “triple bottom line approach” and in addition to the social, economic, and ecological aspects of design for sustainability examine the important role of culturally dominant worldviews, consciousness, and value systems. By addressing personal transformation, group dynamics and interpersonal relationships, as well as non-violent communication, consensus decision making and conflict facilitation these programmes offer the vitally important ‘software’ of a more sustainable culture without which the ‘hardware’ of sustainable technologies and infrastructure designs will be doomed to fail.

The EDE and the FCS programme address what Willis Harman (1998) called “global mind change” — the crucial role that the evolution of human consciousness and associated changes in worldview play in the transition towards a culture of sustainability. Ken Wilber’s framework of integral theory (Wilber, 2001) and the work of Beck and Cowan (1996) on spiral dynamics offer useful intellectual frameworks for exploring the transition into a holistic and participatory worldview that will create the lifestyle changes necessary for sustainability.

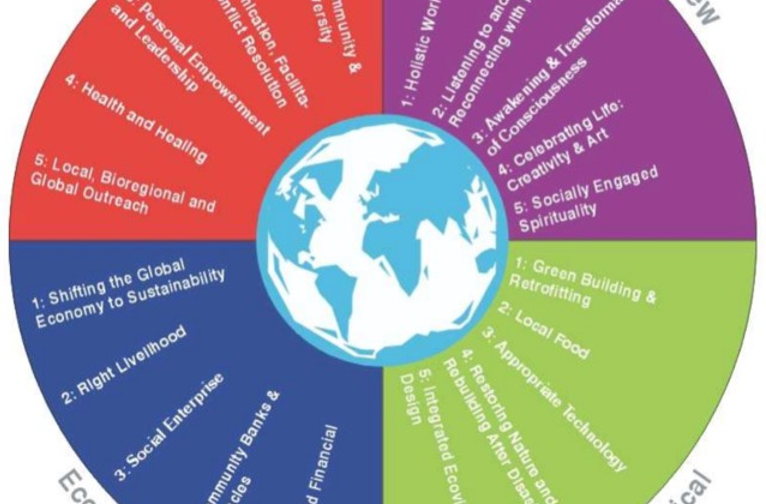

The diagram below (see Fig.1) gives an overview of the four dimensions of the Ecovillage Design Education curriculum. It emphasizes the importance of the psychological (inner) dimension of the shift towards a culture of sustainability by not subsuming it under the social (outer) dimension of the traditional ‘triple bottom line’ approach.

Fig.1: Diagram of the Four Dimensions of the Ecovillage Design Education Curriculum; Source: www.gaiaeducation.org

The international EDE courses and the FCS programme are designed around an experiential, participatory learning approach aimed at increasing social and ecological literacy, stimulating a sense of local and global responsibility, and enabling students to become active co-creators of a culture of sustainability (see Mare, 2004). They offer a deeply transformational learning experience that is both practical and theoretical.

In a paper entitled ‘The Ecovillage as a Living Cell’, Chris Mare (2000) compares how the biological structure of a living cell can provide a metaphor for the design of sustainable communities. Mare argues: “The intellectual discipline that most closely accommodates the synthesis of biology and human settlements … is ‘Ecovillage Design’”(p.5). Expanding on the metaphorical design analogy, he proposes that sustainable human settlements could be regarded as “organs in a bioregional body” itself part of a global network (p.41), and suggests that “human systems must be modelled upon biological systems in order to be sustainable” (p.42).

The EDE curriculum’s design-based approach to sustainability informed by insights from biology, ecology and other natural sciences relates to a variety of nature inspired design approaches such as: ecological design (Jack-Todd & John Todd, 1984; Van der Ryn & Cowan, 1996; Orr, 2002; and Jack-Todd, 2005), bio-logic design or deep design (Wann, 1996), biomimicry (Benyus, 1997), design for sustainability (Birkeland, ed. 2002), and ‘cradle to cradle design’ (McDonough & Braungart, 2002), salutogenic design (Wahl, 2006). The entire EDE curriculum is available to be downloaded on the Gaia Education website.

While this curriculum covers the whole complexity of issues related to designing, creating, and maintaining truly sustainable communities, it was primarily created with vocational course programmes in mind. The next step will be to expand on the existing educational alliances between ecovillages and universities in order to create innovative postgraduate courses in sustainable community and ecovillage design that combine the strength of the EDE curriculum with complementary academic content, best-practice examples, and up-to-date research on sustainable development issues.

4) Universities and Ecovillages: Transformative Learning in Applied Sustainability

In recent years an increasing number of educational alliances have been formed in the UK that bring together traditional university departments and educational charities on the creative fringe of sustainability education. These partnerships have created innovative postgraduate degree programmes providing a more practice-based and participatory approach to education for sustainable development. Many of these programmes are a mixture of residential intensives and distance learning course elements. A number of these courses are listed below. They can be regarded as successful precedents of the kind of masters programmes that could be created at ecovillages:

- MSc. in Sustainable Architecture offered by the Centre of Alternative Technology (CAT) with the University of East London

- Masters in Sustainable Development Advocacy offered by the Bulmer Foundation in collaboration with the University of Worcester

- MSc. in Holistic Science offered by Schumacher College in collaboration with the Environmental Science Department of the University of Plymouth

- MSc. in Human Ecology offered by the Centre for Human Ecology and the Strathclyde University

- Masters in Leadership for Sustainable Development offered by Forum for the Future and Middlesex University

- MSc. in Responsibility and Business Practice of the University of Bath, including an intensive module at Schumacher College

There is a very high potential for institutional synergy between ecovillage-based ‘living and learning centres’ and universities aiming to create up-to-date, participatory and engaging programmes in sustainable development. So far, the majority of such partnerships have been created at the undergraduate level, mostly facilitated by Living Routes, who run semester programmes in ecovillages in India, Senegal, Mexico, Scotland, and Australia. Apart from the Findhorn Foundation ecovillage in Scotland, there are a number of other ecovillages that have independently established links to various universities. These include Auroville (India), Crystal Waters (Australia), and the Ecovillage at Ithaca (USA).

Gaia Education is currently exploring a variety of initiatives to take the EDE approach into universities. The University of Evora, in Portugal, will host an international summer school on ecovillage design in 2008, and the Open University of Catalonia has agreed on forming a partnership with Gaia Education to develop an on-line course in Creating Sustainable Communities based on the Ecovillage Design Education curriculum.

The author of this paper, supported by Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE) Moray, has recently engaged in academic outreach and programme development work for the Findhorn Foundation College. The aim of the initial six month pilot study was to explore new partnerships with Scottish universities and UK academic institutions in order to create novel masters programmes in sustainable development and sustainable community design which would include residential intensives at the Findhorn Foundation ecovillage.

The pilot has been extraordinarily successful, since literally every institution that was approached has expressed a keen interest in taking the proposed collaboration further. While this is no more than a preliminary report and no legally binding agreements have been signed at this point, the Findhorn Foundation College (FFC) in partnership with the Findhorn Foundation and Gaia Education are currently in the early stages of negotiations with a whole range of new academic partner institutions. Below is a list of the potential partner institutions and some of the possibilities that are being explored:

- University of St. Andrews: regular field study visits by students on the undergraduate course in sustainable development; the possibility of the FFC providing an optional masters module for the new MSc in Sustainable Development starting in autumn 2008; the potential of individual research projects being undertaken at the ecovillage

- University of Dundee: already existing supervision of MPhil research on ecological design and ecovillages; possibility of creating an MDes in Design for Sustainability in collaboration with the Centre for the Study of Natural Design, academic support of the Findhorn-based UN training centre CIFAL Findhorn

- Heriot-Watt University: preliminary agreement to go ahead with the creation of a joint MSc. in Integrated Low-Carbon Settlement Design in collaboration with the School of the Built Environment; plans to apply for an EPSRC research grant in order to perform post-occupancy evaluation studies on the ecological housing stock of the Findhorn ecovillage (possibly in collaboration with other Scottish universities)

- Robert Gordon University: The FFC is in dialogue with RGU about the creation of an MSc. in Housing and Advanced Environmental Studies in partnership with the Centre for the Study of Natural Design (University of Dundee)

- Moray College & University of Highlands and Islands: the FFC may create and offer two optional masters modules for a newly to be created MSc. in Sustainability Studies; in the long-term a closer partnership between Moray College, the Sustainable Development Research Centre, and the FFC will be of mutual benefit

- Schumacher College & The Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT): Agreement to continue the development of a joint masters programme with residential intensives at Schumacher College, CAT, and Findhorn. The working title is currently MSc. in Sustainability Consultancy and an academic partner still needs to be determined.

The pilot study clearly demonstrated a high potential for creative education alliances between the Findhorn Foundation College and UK academic institutions. The author is confidant that most, if not all, of the programmes mentioned above will be created between January 2008 and autumn 2009. The limits for such educational alliances are set by the maximum amount of students that could be sustainability integrated into the daily life of the community and not by the lack of potential academic partners.

The Findhorn Foundation ecovillage is an ideal sustainability field study site for a number of reasons, among them: its community owned wind park, community currency and community businesses, extensive eco-housing stock, community supported agriculture, sustainable transport scheme, diverse renewable energy use, ecological sewage treatment facility, experience in group dynamics and conflict facilitation, community lifestyles and proven reduced ecological footprint, as well as, its long experience in providing transformative education. The ecovillage is an ideal partner in the creation of practical academic courses taking a truly holistic approach to sustainable development.

5) Conclusion

The psychological (inner) dimension of the transition towards a culture of sustainability has so far been often overlooked and neglected. Sustainability is not a fixed state of affairs brought about by a series of technological fixes and top down policy decisions. Rather, it is a community-based process of learning how to participate appropriately in constantly and increasingly rapidly changing social, environmental and economic complexities.

As such, the creation of a culture of sustainability requires full participation by ecologically and socially literate citizens, responsible business practices, and inspired political leadership. This can only be achieved by new approaches to life-long learning and education facilitating changes in worldview and value systems. In turn, increased awareness and transformations in consciousness will form the basis for widespread changes towards more sustainable lifestyles. Such lifestyle changes are a prerequisite for a successful transition towards sustainability.

The kind of education for eco-social literacy and transformative learning that is required for such a profound change in society’s basic assumptions, aspirations, and worldviews cannot be effectively provided within traditional academic institutions. Ecovillages provide ideal settings for such transformative education to take place. They can act as living classrooms in which a truly holistic approach to education for sustainable development can be put into practice.

Recent studies of the ecological footprint of various ecovillage communities have consistently demonstrated that a drastic reduction in environmental impact and carbon emissions can be achieved through ecovillage design while maintaining and often increasing the quality of life of residents. Clearly there are a set of transferable insights and skills that have been generated within the diversity of international ecovillage experiments which are now waiting to be successfully applied in existing rural and urban communities, as well as, to the creation of a new form of developer-led and resident engaged sustainable settlements within the context of the UK government’s plans to create 2 million new homes by 2020.

Education alliance between ecovillage-based ‘living and learning centres’ like the Findhorn Foundation College and universities offer an important vehicle of facilitating the transference of ecovillage design lessons into the cultural mainstream. They provide an ideal opportunity to create truly transformative postgraduate courses.

Graduates will have the required levels of eco-social literacy, the understanding of a holistic participatory worldview, the ability to think and act across traditional academic disciplines, and the design skills necessary to sustain their personal and professional actions as catalysts of the emergence of a culture of sustainability throughout their lives.

As highly capable and aware generalists, who can cope with the interconnected social, ecological, economic, and psychological challenges of sustainability, the graduates of ecovillage-based education programmes will be sought after by businesses and government agencies alike. They will be perfectly placed to start up their own businesses or to act as consultants. Education alliances between ecovillages and universities will create graduates who are capable of playing and active role in the transition towards a sustainable culture.

[NOTE: This paper is 10 years old! Neither the Sustainable Development Research Centre nor the masters courses mentioned still exist. We did succeed in creating one of them with Heriott Watt University in Edinburgh. The MSc in Sustainable Community Design had 2 core modules taking place at the Findhorn ecovillage and the video below demonstrates that it was very effective. Our students went on to win prizes with what they learned at Findhorn and all three years of the masters were marked by the same feedback: how the time at Findhorn was the most transformative part of the whole programme and helped students to reorientate their professional practice towards a more holistic approach committed to making a positive difference. Gaia Education has developed impressively since then and the ‘Design for Sustainability’ online course has a steadily growing number of students with graduates in roles of leadership in many sustainability projects around the world.]

Daniel Christian Wahl is the author of the internationally acclaimed book ‘Designing Regenerative Cultures’ (2016).

Short video about the Findhorn Modules of the MSc in Sustainable Community Design (Findhorn College & Heriot Watt University, School of the Built Environment —the course ran in 2011, 2012, and 2013 and was then merged with another programme without the Findhorn modules. By that time I had left Scotland and was only a visiting teacher on the programme.)

The paper continues with Acknowledgements and References:

Acknowledgements

Martin Johnson, Ian Fraser, Nicky Cuthbert (Highlands and Islands Enterprise Moray), Diane Nance-Kivell, Dr. David McNamara (Findhorn Foundation College), Jonathan Dawson (Global Ecovillage Network), Dr. Ross Jackson, Hildur Jackson (Gaia Trust), Dr. Daniel Greenberg (Living Routes), Judith Bone, Geoffrey Colwill, David Fuford (Findhorn Foundation), Prof. Seaton Baxter (Centre for the Study of Natural Design), May East, Chris Mare, and all the members of Gaia Education.

References:

Barlow, Zenobia (2004) ‘Confluence of Streams: An Introduction to the Ground-breaking Work of the Centre for Ecoliteracy’, Resurgence, №226, pp.6–7

Beck, Don & Cowan, Christopher (1996) Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change, Blackwell Business Publishers

Benyus, Janine (1997) Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, Harper Collins

Birkeland, Janis ed. (2002) Design for Sustainability: A Sourcebook of Integrated Eco-logical Solutions, London: Earthscan Publishers

Bower, Chet A. (2001) Educating for Eco-Justice and Community, University of Georgia Press

Capra, Fritjof (2002) The Hidden Connections: A Science for Sustainable Living, Harper Collins: New York

Capra, Fritjof (2004) ‘Landscapes of Learning: Experiencing Ecological Relationships and Community is the Key to Ecological Literacy’, Resurgence, №226, pp.8–9

Capra, Fritjof (2005) ‘Preface: How Nature Sustains the Web of Life’, in Stone & Barlow, edits. Ecological Literacy: Educating our Children for a Sustainable World, The Bioneers Series, Sierra Club Books, pp.xiii-xv

Dawson, Jonathan (2006) Ecovillages: New Frontiers of Sustainability,Schumacher Briefing №12, Green Books

Dawson, Jonathan (2007) Findhorn Foundation Press Release (18 April 2007) ‘Scottish Community Scores Lowest Ecological Footprint Ever Recorded’

Gaia Education (2005) Ecovillage Design Education Curriculum, (www.gaiaeducation.org)

Gilman, Robert (1991) Ecovillages and Sustainable Communities, In Context Institute, www.incontext.org, USA

Goodwin, Brian (2001) ‘Holistic Education in Science’, Society of effective and Affective Learning Conference Proceedings, pp.40–43

Harman, Willis (1998) Global Mind Change: The Promise of the 21st Century, Institute of Noetic Sciences, Berret-Koehler Publishers

Hollick, Malcolm & Connelly Christine (1998) Sustainable Communities: Lessons from Aspiring Eco-villages, Praxis Education, Western Australia

Jackson, Hildur & Svensson, Karen edits. (2002) Ecovillage Living: Restoring the Earth and Her People, Gaia Trust & Green Books

Jack-Todd, Nancy & Todd, John (1984) Bioshelters, Ocean Arks, and City Farming: Ecology as the Basis of Design, Sierra Book Club: San Francisco

Jack-Todd, Nancy (2005) A Safe and Sustainable World — The Promise of Ecological Design, Island Press

Kennedy, Margit & Kennedy, Declan edits. (1997) Designing Ecological Settlements: Ecological Planning and Building — Experience in new housing and the renewal of existing housing quarters in European countries, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin

Mare, Christopher E. (2000) ‘The Ecovillage as a Living Cell — Biological Structures and Metaphors’, Village Design Institute, USA

Mare, Christopher E. (2004) ‘Theoretical Framework for the Ecovillage Design Education’, Village Design Institute, USA

Mare, Christopher E. ed. (2006) Ecovillage Design Education Curriculum(Version 4.0), Gaia Education, Global Ecovillage Educators for a Sustainable Earth (GEESE), and Global Ecovillage Network (GEN), www.gaiaeducation.org

McDonough, William & Braungart, Michael (2002) Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, North Point Press

Meadows, Donella (2001) ‘Dancing with Systems — What to do when systems resist change’, The Whole Earth Review, winter edition

Orr, David W. (1992) Ecological Literacy — Education and the Transition towards a Postmodern World, State University of New York Press

Orr, David W. (2002) The Nature of Design — Ecology, Culture, and Human Intention, Oxford University Press

O’Sullivan, Edmund (1999) Transformative Learning — Educational Vision for the 21st Century, London: ZED Books

Steinberg, Sarah (2007) ‘How I learned to hug a windmill: An Inside look at the Findhorn Community Semester’ Communities Magazine, Issue 134, pp.52–55

Sterling, Steven (2001) Sustainable Education — Re-visioning Learning and Change, Schumacher Briefing №6, Green Books & Schumacher Society UK

Stone, Michael K. & Barlow, Zenobia eds. (2005) Ecological Literacy — Educating Our Children for a Sustainable World, The Bioneers Series, San Francisco: Sierra Club Books

Tinsley, Stephen & George, Heather (2006) Ecological Footprint of the Findhorn Foundation and Community, Sustainable Development Research Centre

UNESCO (2007) ‘Highlights on Decade of Education for Sustainable development — Progress to Date’

Van der Ryn, Sim & Cowan, Stuart (1996) Ecological Design, Island Press

Wahl, Daniel C. (2005) ‘Eco-literacy, Ethics, and Aesthetics in Natural Design: The Artificial as an Expression of Appropriate Participation in Natural Process’, Design System Evolution, European Academy of Design Conference 2005, Bremen, Germany, Paper №92

Wahl, Daniel C. (2006) Design for Human and Planetary Health: A Holistic/Integral Approach to Complexity and Sustainability, PhD Thesis, Centre for the Study of Natural Design, University of Dundee, Scotland

Wahl, Daniel C. (2006) ‘Bionics vs. Biomimicry: from control of nature to sustainable participation in nature’, Design & Nature III: Comparing Design in Nature with Science and Engineering, WIT Press: Southampton & Boston, pp. 289–298

Wahl, Daniel C. (2006) ‘Design for Human and Planetary Health: a transdisciplinary approach to sustainability’, Management of Natural Resources, Sustainable Development and Ecological Hazards, WIT Press: Southampton & Boston, pp.285–296

Wahl, Daniel C. (2007) ‘Scale-linking Design for Systemic Health: Sustainable Communities and Cities in Context’, International Journal of Ecodynamics, Wessex Institute of Technology Press, Vol.2, №1, pp.57–72

Wann, David (1996) Deep Design: Pathways to a Livable Future, Island Press

Wheeler, Keith A. & Bijur, Anne P. edits. (2000) Education for a Sustainable Future — A Paradigm of Hope for the 21st Century, The Centre for a Sustainable Future, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers

Wilber, Ken (2001) A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science, and Spirituality, Gill & Macmillan: Dublin