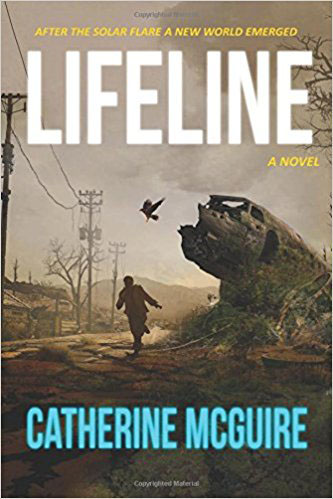

Lifeline: A Novel

Lifeline: A Novel

By Catherine McGuire

472 pp. Founders House Publishing – Mar. 2017. $19.99.

If an intense solar flare were to hit Earth today, it would have the potential to halt civilization as we know it. Just as the massive sun storm of 1859 unleashed enough electromagnetic interference to disrupt the global telegraph network, so too could a future solar discharge cause modern-day communications and power systems to fail. People unfortunate enough to be on the side of the planet facing the sun would suddenly find themselves in the situation many Puerto Ricans faced following Hurricane Maria in the fall of 2017. Access to basic things like lighting, refrigeration, heating, modern medicine and water treatment would abruptly vanish.

The scale of the resulting mayhem is almost too much to contemplate, but Catherine McGuire has thought long and hard about it anyway, making it the backdrop for her novel Lifeline. McGuire’s book is an adventure that scores on every front, from its tense action scenes, to its finely realized characters and emotionally involving drama, to its richly rendered settings, to the intriguing irony of its double-entendre title. And while the novel does have moral lessons to offer, McGuire rightly refuses to let these take precedence over the story. For she knows that morals are more effective when subtly conveyed in the background of a believable, moving tale than when spelled out explicitly.

It’s the late 21st century, and communities throughout what is now the eastern United States are still recovering 50 years after a historic solar superstorm. Our main character, Martin Barrister, is a communications company employee in a world without working satellites. All the satellites were ruined by the flare, so non-satellite-dependent means of communication and data transmission are now the norm. Martin’s employer, Commco, is New York City’s communications monopoly, and it has sent him on a journey to search for potential partners in the development of a non-satellite-based relay tower system. Martin’s bosses hope he can persuade at least two outlying towns to provide maintenance on a couple of new towers in exchange for access to their signals.

But Martin soon notices that a number of key things about his mission aren’t jelling. He’s turned down cold by the first town he visits, which suggests either that whoever sent him didn’t do enough research, or that his entire trip has been a sham. Then Martin is abandoned by his guide and attacked by hoodlums. Eventually Martin pieces together that Commco and the New York City government have thrown him into an impending war zone as bait to gather intel about a rebel army moving north from Fort Cumberland. The rebels are intent on breaching Pittsburgh’s defenses as part of an effort by Washington, D.C., to challenge New York’s hegemony. If you’re confused by all this, don’t worry; so is Martin.

Following Martin’s run-in with his assailants, a good Samaritan named Ciera offers to help him find his way back to the nearest railroad terminus, so that he can return to New York. This gesture perplexes Martin, who isn’t used to kindness from strangers. In their days traveling together—going by bicycle and horse—the two become well acquainted. As they converse, they continually argue over their disparate outlooks, Martin with his city-bred individualism and Ciera with her orientation toward nature and community. In one revealing scene, Ciera explains to Martin, “In the country, you don’t play people like options—you treat them like friends…or enemies.” Another telling moment occurs when Ciera and Martin encounter a homeless man. Horrified that any community would let people starve, Ciera says in disbelief, “I’m surprised they allow it.” But Martin misunderstands her, thinking that she means she’s surprised the local community would permit a beggar inside its borders.

Ciera lives in Evansville, a community that prides itself on its self-sufficiency ethic. The people of Evansville resolved long ago to curtail their dealings with other communities, deciding that they would fare best by relying on one another as opposed to the outside world. While they do trade and cooperate with other communities, they’re cautiously selective, which is why their town’s existence is a closely guarded secret.

The place where Martin spent his formative years couldn’t be a starker counterpoint to Evansville. Far grittier and more unforgiving than present-day New York, it’s a city where altruism is a foreign concept. It’s also the exact opposite of sustainable, relying on plunder rather than nature for its survival. The citizenry is lorded over by an authoritarian regime that monitors every block with cameras, behands thieves, performs public executions and sends out Army tanks to crush unrest. New Yorkers accept such atrocities as a tradeoff for the many benefits of city life, which include running water, digitally recorded music, “mu-vid theaters,” antibiotics and the pathogen-free, vat-grown meat known as “pink.” People don’t seem to mind that their experience of nature is limited to a tame, human-made imitation of a natural setting squeezed in between two of Manhattan’s vast, bustling avenues.

Thus, the culture shock Martin feels at the beginning of his trip is extreme. The lack of familiar city sounds and activities, together with the strange customs he observes among locals, brings him great anxiety. He’s especially unsettled by people’s touching behavior and degree of physical closeness, since for city people close physical contact from a stranger is perceived as a threat. But as the days roll on, life outside the city grows on Martin. He comes to greatly admire the new culture, as well as the cunning everyone around him has shown in managing to get by without any help from the city.

Martin’s character arc is believable and emotionally satisfying. At first, he’s motivated solely by self-preservation and a desire to return to the city as quickly as possible. But alas, Martin is cursed with a conscience, and thus is unwilling to be as ruthless as the usual city person. (Indeed, one of the running jokes about Martin back in New York is that he never was vicious enough to be a “shark.”) Martin realizes that with the rebels hard on his heels, he’s jeopardized the safety of every town he’s visited. This makes him feel morally obligated to delay his return home so that he can help protect the local communities against the rebel advance.

Lifeline takes on the feel of an espionage thriller when Martin goes on a series of missions as part of an effort to repay others for the favors they’ve done for him. Martin spent much of his young adulthood in slum gangs, where he learned to fast talk and put on multiple identities like a Roma wanderer. He makes good use of these skills in defending one community against a pack of marauders, and then in helping another group evade Pittsburgh’s elaborate surveillance system in order to erect a comm tower within that city’s borders. This latter mission involves traveling through sewers and secret passageways, walking high-beam style over a perilous chasm and using a long-abandoned subway tunnel to go underneath a river (a disconcerting concept to Martin).

In addition to advancing the plot, Martin’s travels through different communities allow us a glimpse of the technological landscape of this future. The scarcity of the times and the loss of any large-scale manufacturing capability mean that this landscape is mostly salvage. Far-apart communities stay in touch with antique ham radio technology, used hospital scrubs are now fashionable tunics and bone meal made from exhumed human remains is used in some locales to fertilize crops. America’s defunct automobile infrastructure has also been recycled, with asphalt and metal from street signs being melted down to make things more sorely needed.

The dominant technologies of Evansville and other rural communities are defined not only by their retro design but also by their naturelike quality. The communities that thrive are those that know the necessity of cooperating with nature rather than trying to conquer it. So, instead of burning fossil fuels to cook food and heat water, people heat and cook using devices that run on passive solar energy, such as hay box cookers and solar water heaters. In place of our massively wasteful flush toilets, there are composting toilets. In lieu of machines powered by electricity or internal combustion, most devices use human or animal muscle. This is especially true when it comes to travel, with most people getting around on foot or by horse. As for waterway travel and transport, the sail has come back in a big way, as have ox-powered paddle wheel boats.

This novel’s ultimate message is one of reassurance. While it makes no bones about the inevitability of our civilization’s decline—with or without the intervention of a solar flare or other natural cataclysm—it tries to show that this need not be cause for despair. Even under drastically changed circumstances, it will still be possible for future generations to lead the sort of rich, enjoyable lives we see people living in Lifeline.