I recently had the pleasure of giving a keynote talk at Cambridge University. Darshil Shah, the brilliant academic who organised the summer school on biomaterials put me first to broaden the system perspectives of the phd and early career researchers. Titled, ‘provisioning a place-sourced, bioregional future through natural systems and small supply chains’, I first gave a quick run through my background as a designer turned educator searching for sustainability and how this lead me back to grassroots action.

One of my steps back to practice was receiving a Churchill Fellowship. In early 2024 I travelled through Europe to investigate small scale machinery and cooperative methods to support the growing, processing and production of flax and hemp. What follows is part 1 of a lightly edited version of the Cambridge talk, part 2 will follow in my next post.

Most readers are probably quite familiar with the frames of commoning and bioregionalism but this is where we begin……

What is a Bioregion?

A bioregion shares ecological, geographical and cultural characteristics. It starts with ecology and the landscape. Often defined by watershed or geographical boundaries. Bioregionalism is more than a philosophy — it’s a way of life rooted in place. It asks us to align our politics, culture, and economy with the natural boundaries of watersheds, soil and terrain.

A fibreshed is formed along the same lines as a bioregion. Conceptually developed in America by Rebecca Burgess, it considers a soil to soil circular system of fabric and clothing creation, where fibres are grown, processed and worn in place. Clothing is an important fundamental human need that must be provisioned for. We all wear clothing, it sits on our bodies and can be a direct way to connect to land and community once you start to think about it, which many people don’t.

What is a Commons?

Moving onto the commons, this can be privately owned land where people have historical rights, such as fishing, grazing animals or collecting wood, or it can refer to a model of collective ownership and stewardship of shared resources. We are steeped in the commons in the UK – we have a house of commons, we are commoners, people are ‘common’.

Guy Standing, economist and commons advocate, often talks of the Charter of the Forest developed in 1217 which was meant to protect the rights of common people. Over the years our commons were enclosed which essentially forced ‘common people’ into industrial servitude to feed the fires of capitalism. It is claimed that many people used to live happily on commons, fishing, hunting, collecting firewood etc and did not want to work in factories. Between 1760 and 1870, over 4,000 acts of Parliament, instituted by a landowning elite, confiscated seven million acres of commons. We are still suffering the consequences of that action today.

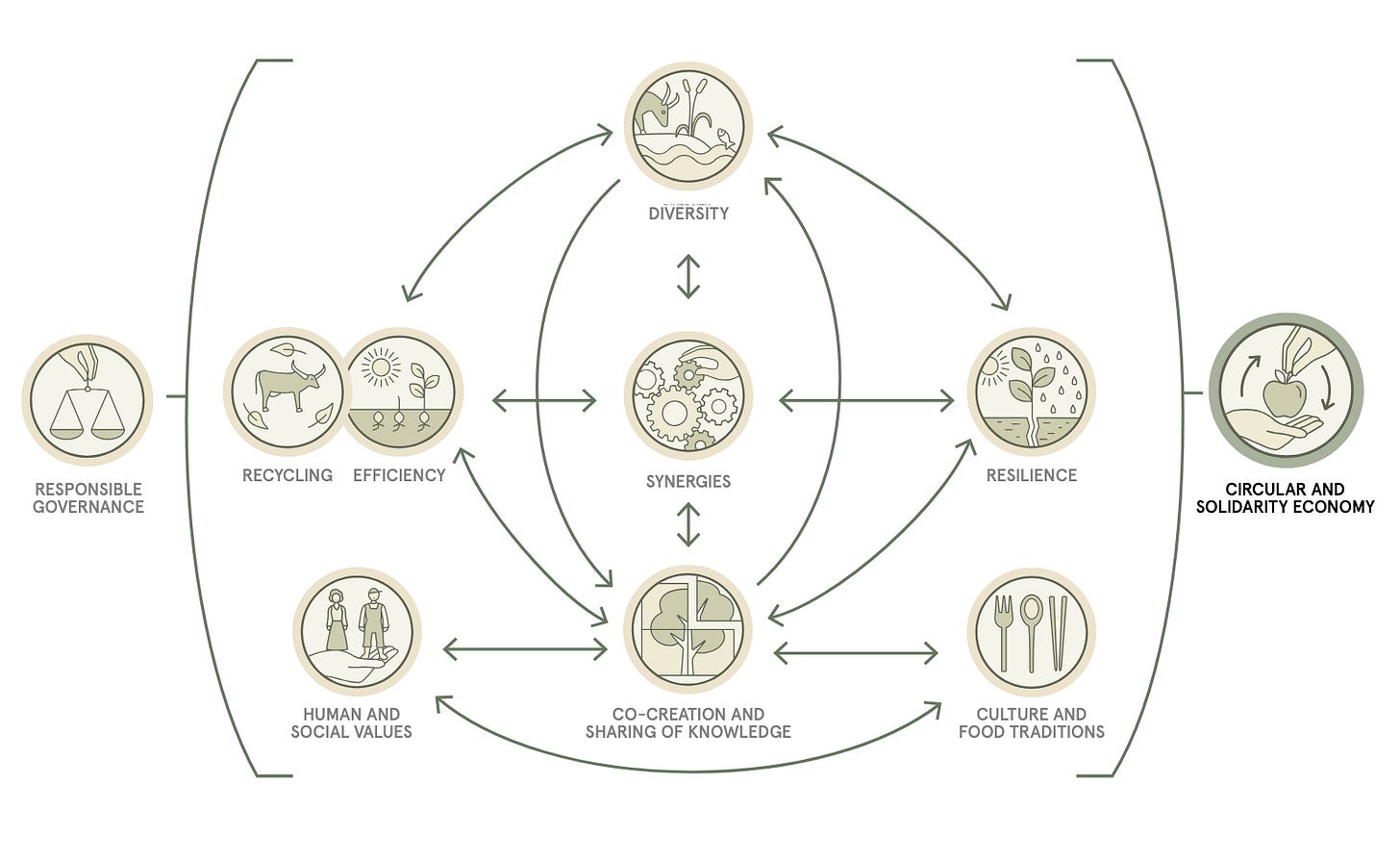

According to David Bollier, commons-based transformations will “allow overshooting systems to find new ways to work within the biocapacity of their own regions”. The systems and governance we use to grow and produce bioregional materials is as important as the materials themselves. Commons theory, as developed by David and his late academic partner Silke Helfrich, frames commoning as a social practice of collective stewardship, grounded in care and relational accountability.

Bast fibre systems that prioritise knowledge-sharing, shared infrastructure, and cooperative governance over profit can be understood as acts of commoning. These practices resist enclosure and extraction, offering models of textile production as cultural and ecological care. A commons is not just a resource. It’s a self-organised social system where human practices and social culture help to make the shared use of a resource work.

My interpretation of Commoning means collectively caring for social networks, knowledge, cultural practices, heritage and resources which are shared for the benefit of everyone in the community. As Bollier states ‘ it is an activation of relationships that bind communities together’ and that ‘these concepts create a framework from which to experiment and build new ways of working together and generates value in ways not easily captured by markets and prices’.

Cosmopolitan Commoning

Cosmopolitan Localism connects communities globally through shared exchange in production and consumption. Distributed and micro-scale production systems, embed production within communities supported by shared technologies. Cosmo-Local Production extends this by localising material production near source and market while using global knowledge to drive innovation and community voice. Examples include Farm Hack (US), L’Atelier Paysan (France), Wikihouse, and Open Food Networks (UK).

The term cosmo-local commoning succinctly describes an ethos underpinning the supply chains of alternative modes of production. I love to use this phrase as I feel it describes a very sensible method of working where we can learn, share knowledge and develop enterprise in many places concurrenlty.

So how do we apply all this theory to linen and textile supply chains?

Agroecology

Everything begins with cultivation, with growing and land. With bast-fibres this involves understanding agronomy, soil, biodiversity, drilling seeds, managing weeds, harvesting and retting straw (in fields or in tanks). Flax and hemp can support organic crop rotations whilst creating valuable and useful outputs. They can also support biodiversity and reduce our use of plastic.

We need farming systems that work in alignment with ecological processes rather than treating nature as a production input. Agroecology offers a framework for such alignment, emphasising farming that works with nature and manages the balance of relationships between plants, animals, people and their environment. Rethinking cultivation begins with organic growing and agroecology. The 10 elements of agroecology developed by the food and agriculture organisation of the UN provide a great explanation of how this works.

Land-use

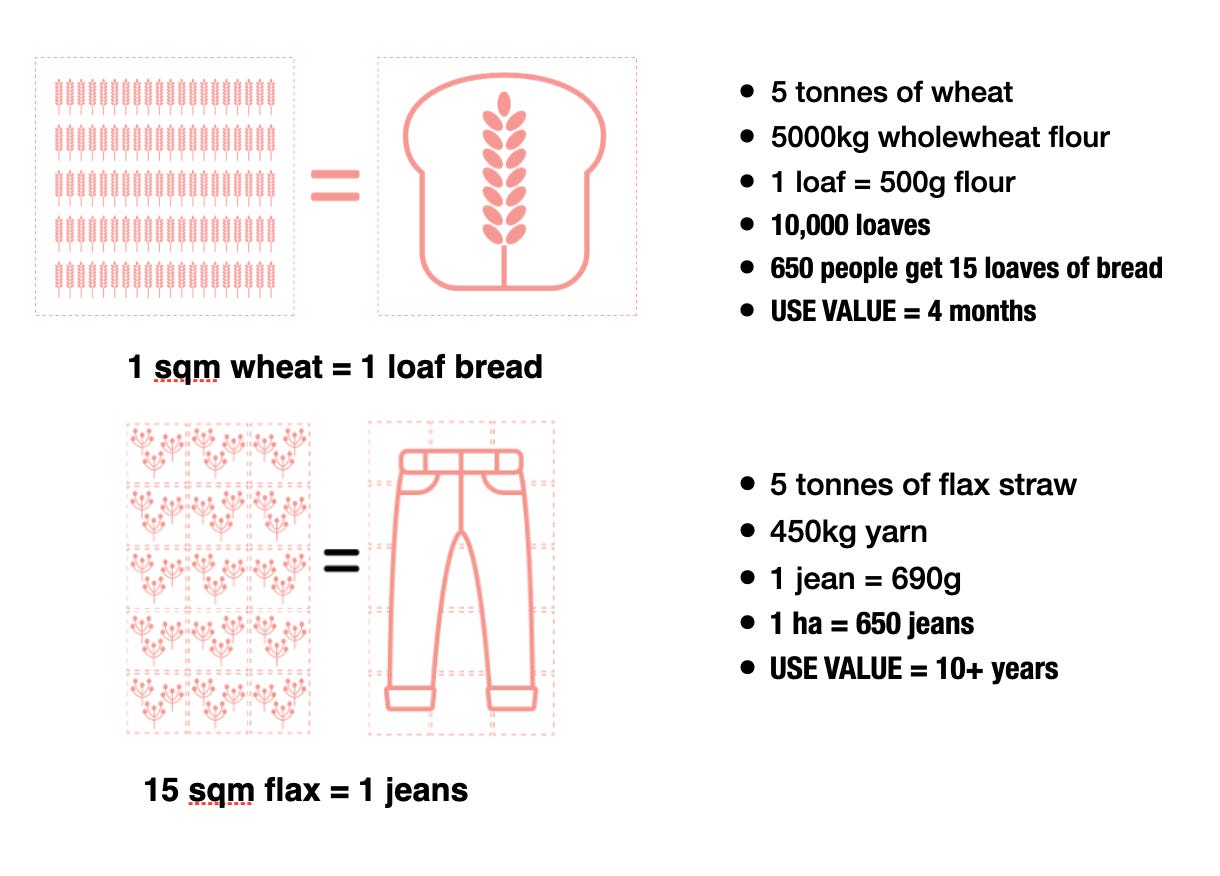

Working with land requires thinking about land use. Some may question whether a country should give over a proportion of its arable land to growing textile material when food should take priority, and this is a valid concern. However we eat food all the time whereas textiles can be in use for many years.

These are playful but carefully calculated estimates that show that one hectare of carefully managed land can make 10,000 loaves of bread or 650 pairs of jeans. The use value of the land over time is very different – these thought experiments show how little land would be taken up by growing flax for textiles, bread is consumed quickly whereas well-made jeans can last many years. There could be room for both.

Re-thinking production scale

Once we’ve considered the land involved in supply chains we need to think about the scale at which we will operate. One of the many stumbling blocks to creating localised, UK fibre is the extensive machinery needed to turn raw plant material into practical value such as insulation, growing medium or textile yarn. In my research I’ve been looking at bast fibre equipment and process at various scales to consider how to best support localised fibre production and meaningful livelihoods.

There are many steps and plenty of processes involved in flax to linen creation. Once grown, harvesting flax requires a specialist flax puller and the Europeans have machinery to handle this of varying sizes. Post harvest, flax requires retting (rotting), in some places this is completed in tanks but in France and Belgium ‘dew retting’ takes place in the field over 3-6 weeks. Once baled, the flax is transported to a nearby scutching mill. After rippling where the seeds are removed, the flax is broken, breaking involves the crimping of the plant through geared wheels, then scutching, where blades bash the fibre in a circular flow to remove all the shives (the woody outer core). Finally we have hackling, where the fibre is drawn through a series of progressively narrowing combs to produce a smooth, blonde, ponytail bundle of flax. Breaking and scutching machinery is not complicated to build and with the right technical plans, can be made by any local fabricator.

Large Scale mill

This is an example of a large scale scutching mill in France. Scutching facilities are abundant in Normandy and Belgium but they are rare in many European locations and lie at the root of why new linen production is difficult.

In the UK our last flax mills closed in the 1950’s but these were a temporary war measure and most of our linen industry in England was gone long by end of the 19th century. Flax and linen production seems to have aligned with wars in previous centuries, furnishing aeroplanes, creating fire hoses, uniforms etc.

Mid Scale Mill

This image shows a medium scale scutching mill at Mallon Linen in Ireland where Charlie Mallon and Helen Keys are singled handedly reviving Irish linen. A strangely challenging endeavour for a country that was a global leader in linen production.

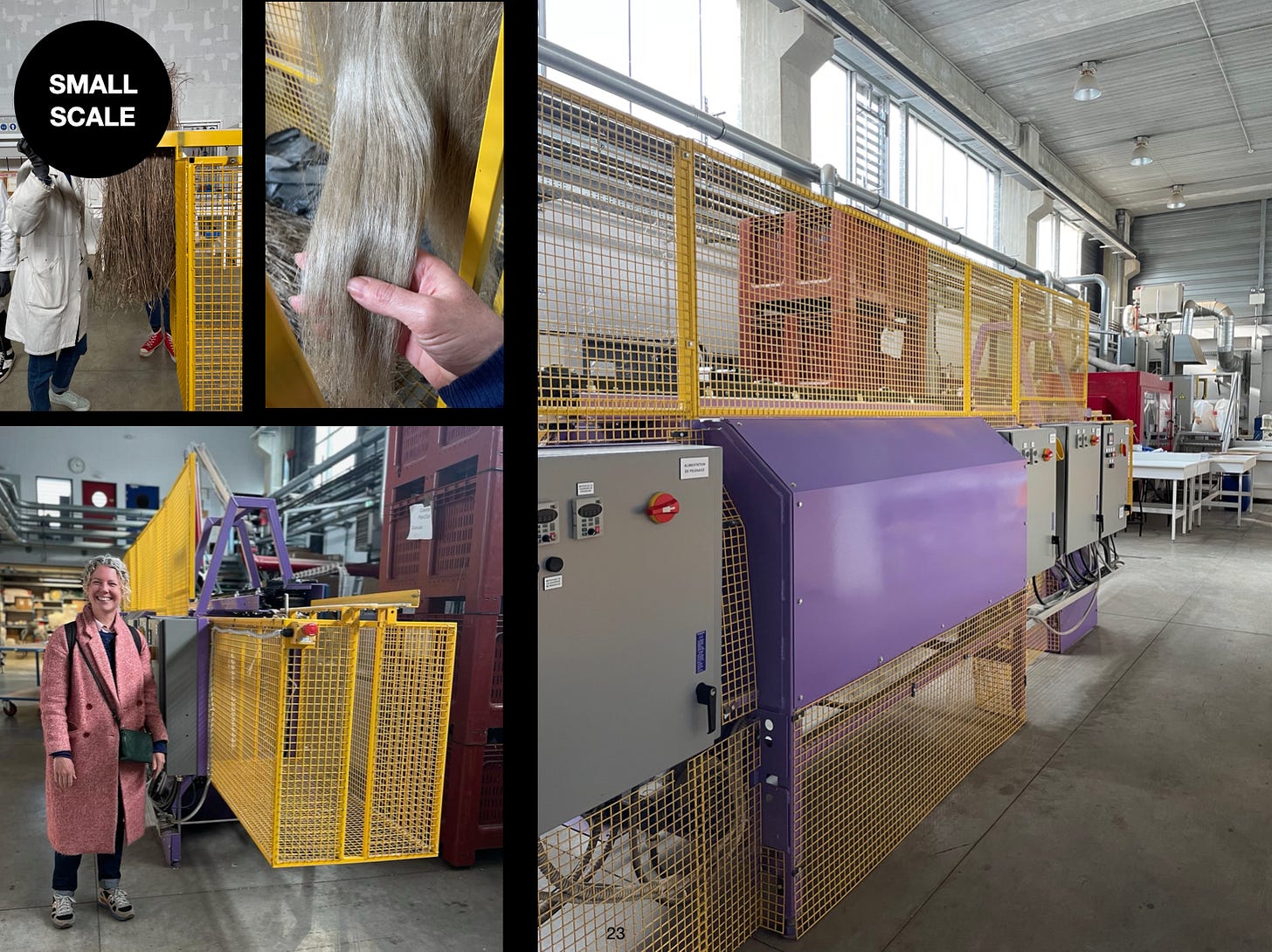

Small Scale Mill

A new scale to consider is something that could work on small farms and fibre collectives. These are scutching machines from Taproot Fibre, developed by flax pioneer Patricia Bishop in Nova Scotia, Canada. I saw them at work at the École Nationale D’Ingenieurs De Tarbes. Professor Pierre Ouagne, put together a small-scale spinning facility for linen and hemp that also has scutching capability. It was thrilling to see the full process in action from raw plant to final yarn under one roof.

Micro Scale Mill

This is Rosie and Nick at Fantasy Fibre Mill, they are working to a ‘micro-scale’ and having experienced their machines first hand I can say they are much more promising than those developed by TapRoot Fibre. They are inexpensive to develop, adaptable and quick.

Scutching Scales

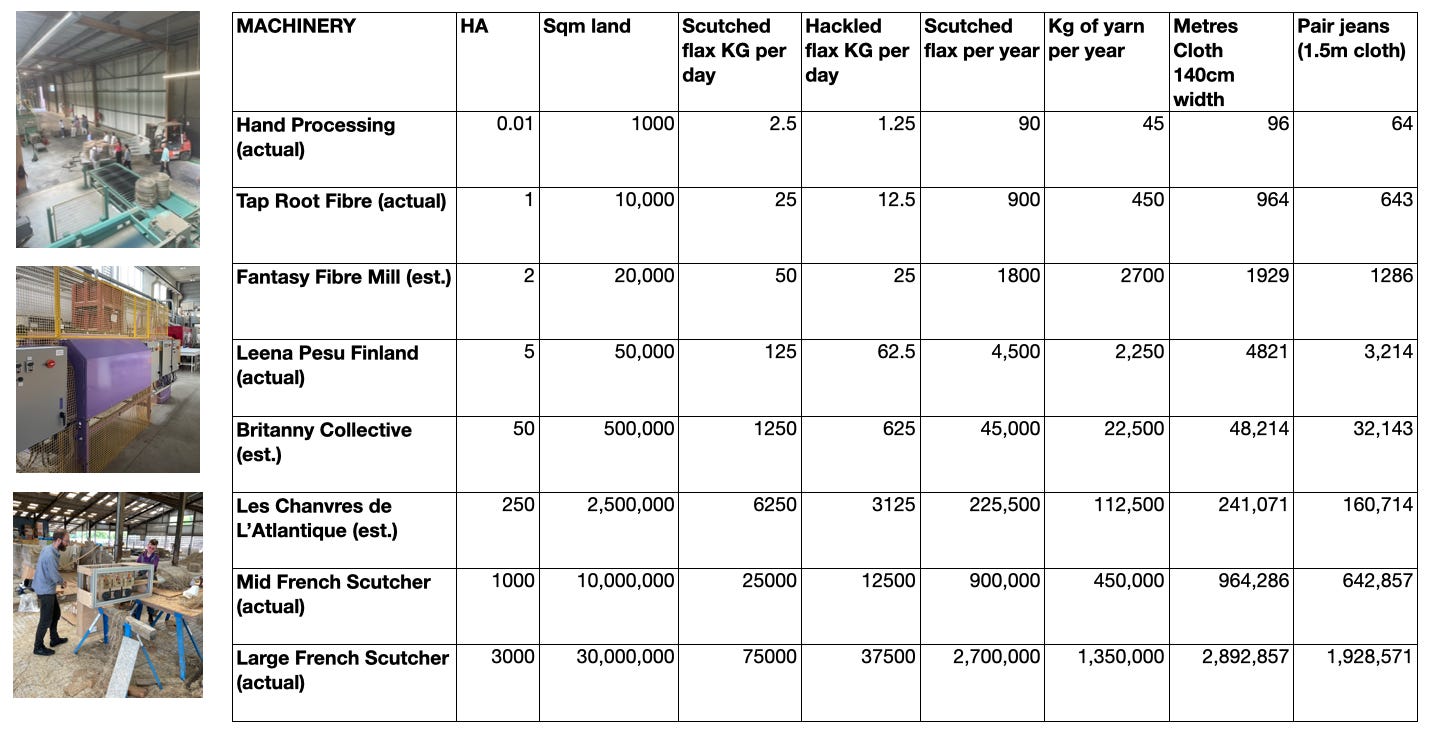

The table below shows processing calculations per hectare using different scales of machinery. Assumptions used are – a low yield of five tonnes of straw, and the machine working an eight-hour day, five days per week for 40 weeks per year. These figures are approximate but well-informed and support illustrations made throughout this section. Please don’t quote me though! The figures have evolved a little from those published in my original Churchill report and may continue to as my knowledge increases.

From the table we can calculate that:

• Large-scale scutching mill machinery set-up costs approx. £15m, services 3000 ha, employs 30 people, creates 3 million metres of cloth or 2 million pairs of jeans.

• Mid-scale scutching mill machinery set-up costs approx. £3m, services 1000 ha, employs 15 people, creates 1 million metres of cloth or 640,000 pairs of jeans.

• Small-scale scutching mill machinery set-up costs approx. £150-300k, services 50 ha, employs 5 people, creates 48,000 metres of cloth or 32,000 pairs of jeans.

• Micro-scale scutching mill machinery set-up costs approx. £15k, services 2 ha, employs 2 people, creates 2000 metres of cloth or 1300 pairs of jeans.

The larger and medium scales will service large areas of land but set-up costs are very high and to make returns on investment would mean competing in volatile global markets. In the UK we would also need investment in expensive infrastructure such as large-scale harvesting machinery and transport networks to move the bales around. We would need to ship the thousands of bales of scutched and hackled flax to a French spinning mill. This entails additional costs, post-Brexit, and makes the UK less competitive in an already difficult market.

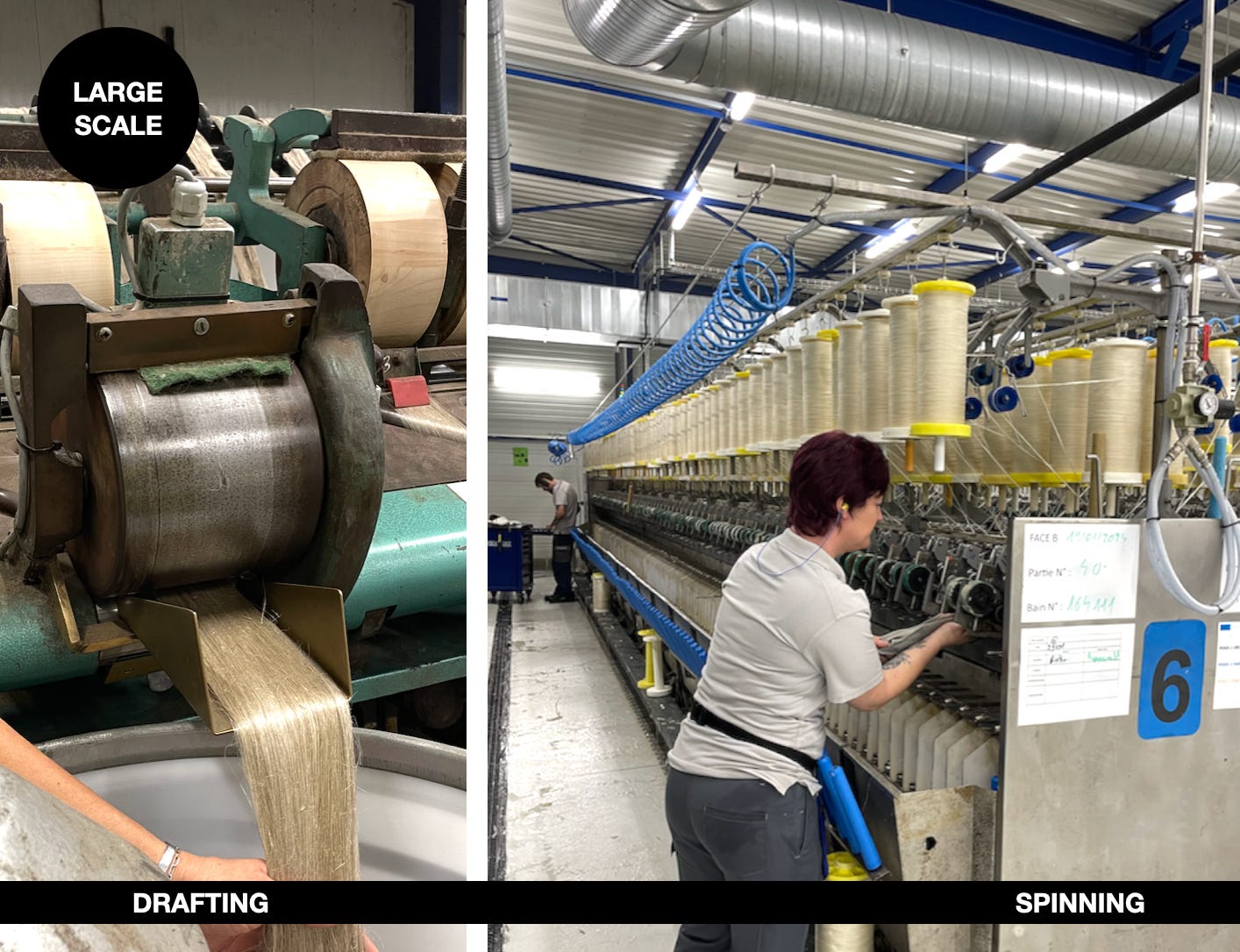

Spinning Scales

After scutching and heckling we move onto to spinning. Spinning flax/hemp can be a wet or dry process starting with sliver which is doubled and drawn into a rove which has twist added and finally spun into yarn, then woven or knitted into cloth. Spinning is the most difficult area of the supply chain to establish. The spinning facility at Tarbes is perfect for micro production, Pierre Ouagne bought some equipment from Linaficio and had the drafting mechanisms made in India, he has a 6 spindle machine.

We can estimate that:

• Large-scale spinning mill machinery set-up cost approx. £5m, services 666 ha, employs 20 people, creates 300 tonnes of yarn or 430,000 pairs of jeans.

• Mid-scale spinning mill machinery set-up cost approx. £2.5m, services 66 ha, employs 5 people, produces 30 tonnes of yarn or 43,000 pairs of jeans.

• Small-scale spinning mill machinery set-up cost approx. £150-300k, services 5 ha, employs 2 people, produces 2.25 tonnes of yarn or 3250 pairs of jeans.

• Micro-scale spinning mill machinery set-up cost approx. £15k, services 1 ha, employs 1 person, produces 0.45 tonnes of yarn or 650 pairs of jeans.

These statements are based on considered but anecdotal estimates however they show that spinning is capital intensive but low on labour. At the micro scale a £15k investment in machinery could support the employment of 1 person, at the large-scale this is £250,000 per person. The French government recently invested millions in a new spinning mill in Normandy.

Yarn will be more expensive at the lower scales, however, if one considers investment value through livelihood creation, through rural resilience, ecological benefits rather than capital accumulation and profit, the picture looks very different.

I’m an advocate for the small and micro scales but I think it’s important that people have the information they need to make decisions suitable for their own contexts.

Open Source Textile Mills

Fantasy Fibre Mill is experimenting at the micro-scale, developing innovative, easy-to-assemble, inexpensive spinning production lines. They work collaboratively with various small-scale, open source, textile machinery enthusiasts across the globe and they are working together on all sorts of easy to assemble, collaboratively developed machinery. They have a fully functioning flax breaker, scutcher and small wool spinning machine, the flax spinner is a work in progress but getting there. This is an example of cosmo local commoning, the group of textile machine enthusiasts use a discord server called Open Source Textile Mills to communicate and share learnings.

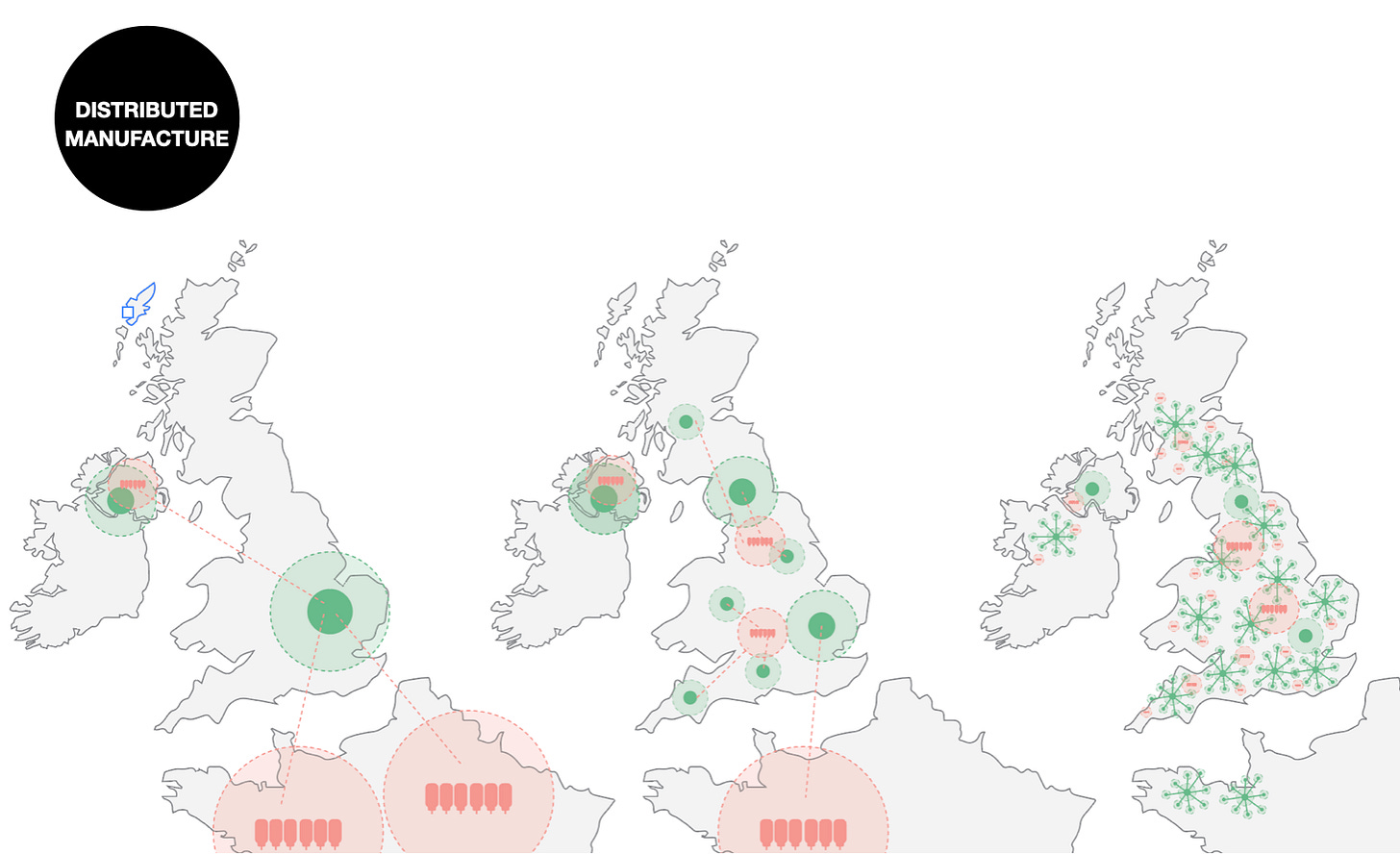

Distributed Manufacture

It matters how we set up any processing infrastructure. These diagrams illustrate the different scales and their potential distribution across an area the size of the UK.

Working at smaller scales means that the benefits of additional crop rotations, processing mills and artisan-micro-maker labs could be spread throughout the country, bringing greater resilience and livelihoods to rural areas. Energy demands would be lower and distributed as processing would be localised and require limited transport.

The scales of machinery could vary depending on the arable potential of an area but it’s easy to imagine 100-plus small-scale distributed facilities in place of one large industrial behemoth. It would provide purpose and activity (jobs) for hundreds of people in place of a few.

The only argument against is this is to support capital accumulation and pricing to make profit for a few shareholders. It’s time to start thinking differently.

I will explore this topic further in my next post and welcome any feedback in the meantime.