What follows is a story involving a movie watched by animals. The pacing of the movie to be described might seem like a very odd choice, but it simply mirrors the pacing of human life on the planet. A vivid visual imagination on your part will help to bring the story to life. So, put on your creative cap and let’s dive in!

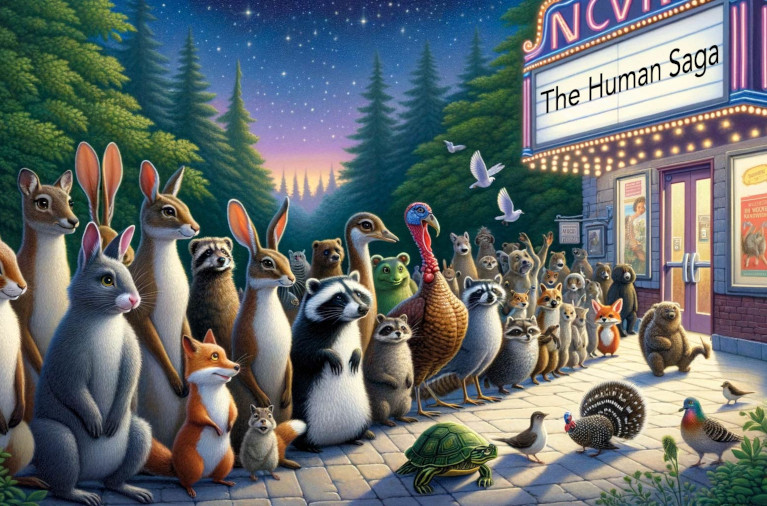

Picture a small-town movie theater on a street so quiet and unimposing that the surrounding prairie and forest sidle right up to the back of the theater. The marquee advertises a feature film called The Human Saga.

As the afternoon shadows lengthen, a trickle of woodland creatures start to emerge from the forest, mosey up to the theater, pay for tickets, and go in. You notice rabbits, a fox, a group of turkeys, a band of raccoons, some stoats, newts, a skunk (who will be lucky enough to sit next to it?), a hoppy group of frogs, some chittering squirrels, a family of porcupines, a pair of doves, an ancient looking tortoise, a doe and her two fawns, and even a mama bear with cubs. They and many others have all come to absorb a tale of what these humans are all about. It’s a long movie: almost three hours chronicling the almost 3 million years of humans on Earth. But it’s fine: no one is in a big hurry.

The animals amicably settle into their seats, enjoying candy, popcorn, and a hot dog here and there. They’re relaxed, but wide-eyed with excitement for this special treat.

Opening Scene

The curtains rise, and the opening scene dazzles the crowd, bathing them in orange light as a bright sunrise radiates from the screen. The only sounds are a gentle whisper of wind and a hint of distant bird song. The animals are at ease: they understand daybreak as well as they understand anything.

The camera pans away from the eastern horizon to reveal that we’re situated on the edge of a forest—not terribly unlike the familiar forest edge behind the theater. A strange but understated noise snags the attention of most of the spectators, who then begin looking (and some sniffing) for its source. Soon enough, they spot two human children squatting next to a mossy log, facing each other—their heads almost touching as they giggle over something. The fox is disappointed at the lack of olfactory representations in this sorry excuse for a theater: so pitifully removed from real experience!

Anyway, as the camera closes in on the children, we come to learn that the source of their amusement is an inchworm crawling along one of their fingers, getting to the end, stretching and waggling into the void to seek a new beginning, then finding—just in time—the other kid’s finger waiting to receive it. Worth a giggle. The audience chuckles too. They’ve all seen inchworms before, and indeed that’s exactly how inchworms behave!

The children make new, excited noises when the inchworm drops on an invisible thread, appearing to hover in space as it slowly descends to the ground. The children allow it to find security on a blade of grass and wipe the thread onto the log to leave their inchworm brother in peace.

It’s just as well, as adult humans begin calling to the kids. It seems it’s time to eat! The camera follows the kids a short way into the forest, where we see a couple dozen people doing various confusing things—some gathered around a circle of rocks with fire and smoke inside. Fire and smoke! This is a little scary for some of the animals watching, but it seems to be staying put and not jumping to the trees—like the elders in the audience know it is prone to do. The spectators recognize some of the food gathered around. Mushrooms, leaves, roots (yes, those kind are good, the porcupines agree). The humans are busy chewing, and drinking water; there’s one scratching his head; another appears to be grooming her friend. Yes: all these are familiar activities. No mistaking that these are animals like ourselves, the viewers think, even if we each do things differently, according to our customs and physiologies.

In its Stride

The movie goes on in much this same way. We see the humans sleeping, playing, singing, foraging for food, and occasionally hunting. The hunting scenes frighten some of the younger critters—especially the young bunnies who tuck their faces into their parents’ fur. But they all understand. This is part of life. Life and death, it is well known, are inseparable. But it is interesting that these animals—who mostly eat plants—also hunt and eat meat like predators. That strikes both the fox and the rabbits as a little odd, but the raccoons are unfazed. All the same, the basics are pretty understandable to the entire gathering. Fascinating creatures, these humans. A worthy film.

The human animals also make a lot of strange noises, and seem to take turns doing so. Maybe it’s a crude version of communication that doesn’t use scent, subtle visual cues, or classic, recognizable vocalizations like shrieks or growls. Their murmurings seem to make them very effective hunters, though. It’s pretty scary, sometimes, how adept they are.

But there are also plenty of antics to laugh at. Their balance isn’t particularly impressive—tottering around on their two hind legs as they do. Lots more slipping and falling than for most animals, which elicit howls of laughter from the crowd. The gangly creatures seem to laugh at themselves, too, and play jokes on each other. They’re alright.

One member of the human clan is obviously pretty old: not as limber as the rest, sporting a spray of white hair, is impressively wrinkled like a rhino, but is obviously much loved and nurtured by the others. Those eyes have seen much, and seem to really understand life: their own, that of their fellow clan members, and indeed the entire community of life. The animals watching sense respect toward themselves and can’t help but to return it. The old one is still capable of roaming with the others, digging out tubers, and often makes the younger ones hoot in merriment after long stretches of making those funny sounds around the smoke-fire.

One morning, after sleeping through familiar nighttime sounds, the old one does not stir. No one is able to wake her. Some wails emerge from members of the tribe, immediately recognized by all to be grief. Yes—we have all known death, the older animals nod and bow their heads. Some of the young can’t face it. Even the bunnies, who endured seeing their kind hunted and eaten by the humans are genuinely sad. A baby porcupine turns his head into the soft belly of his mother, blubbering. Ouch!

These humans might be unusual, and sometimes very scary, but they are fundamentally no different than us—the viewers reflect. Loss is hard. Lots of throats still have lumps as the humans dig a hole in the ground, laying the loved one in it and covering it up. This seems to be a strange practice, but as time goes on, flowers and lush grasses cover the grave. Nearby mushrooms and oaks get an obvious boost. Lots of critters feast on the bounty of vegetation and acorns, to the delight of the squirrels in the seats. It dawns on the animals: Ah: we get it—the humans give back to the community—from microbes to insects to plants to vertebrates of all sorts. Very kind of them.

Wrapping up the Movie

And so it goes, generation after generation, as the hours pleasantly pass. The patterns become familiar and rhythmic. The laughs and tears and awe continue to wash over the crowd. Then, about 15 minutes before the end of the movie, the humans undergo subtle transformations to become a slightly new species: Homo sapiens. Huh. Okay. I guess that’s not too surprising as such things have happened already during the course of the movie—and it’s how all of us got here. As in previous cases, everything seems much as it was before—except perhaps these new folks are even craftier as hunters and even more communicative, if that’s possible. They almost seem to read each others’ minds, and perhaps even those of the animals they hunt. The big animals in some parts of the world start to disappear about five minutes before the end, when the humans migrate away from their cradle where the big beasts knew to be wary of these diminutive but clever hunters. The megafauna disappearance is a bit concerning, but perhaps a tolerable disruption on the whole. It seems like this still could work out: these creatures still obey the law of life like everyone else. Ice ages come and go, and nothing fundamental has changed: only that the “heavy” relatives are missing, sadly.

Just as the movie is about to close, with only about a half-minute left, these jokers start doing something that hasn’t been part of the movie at all until this point. They start knocking down forests and other biodiverse habitats to plow fields and plant them each with a single species, eradicating “weeds,” exterminating “pests” of all stripes (wait, is that us?), and basically acting like they own the place. Even worse, they imprison animals to perform work for them: deciding what and when they eat, where they can go, when and with whom they can mate, and then lazily eat them whenever they want without the “fairness” of a free hunt in the wild. No one is eating popcorn any more, after this turn to animal slavery—they’re hardly even breathing! It’s as if the humans have waged war on the same community of life that had once been respected as family members. Wait: who directed this movie: M. Night Shyamalan? Some animals leave in disgust. Why ruin what had been a perfectly enjoyable and inspiring movie?

For those who stay, it gets even stranger. With fifteen seconds to go, cities spring up. Human population starts to creep upwards. About 1.5 seconds before the end, they appear to acquire magic, beginning to harness fire, lightning, and thunder in new ways. A half-second before the final credits they start burning the remains of ancient life that had been deeply buried for ages upon ages, propelling their rapidly-industrializing machine faster and faster. It’s as if the world detonated in a dazzling fire-ball! In the last blink of 0.2 seconds, non-human vertebrate populations on the planet suffer average declines of 70%—essentially vaporized—as humans explode in number and come to dominate every eco-region on Earth. The audience doesn’t much care for that, let me tell you! Most swarmed out of the theater in a panic. It wasn’t expected to be a horror movie!

Before Rolling Credits…

And that’s how the story is left. What a terrible way to end an otherwise perfectly enjoyable experience! The few remaining animals are left in stunned silence, jaws practically on the floor. It seems like the whole thing just hit a self-destruct at the end. They struggle to pin down exactly where things went truly wrong. I mean, things were unambiguously fine until the last 15 minutes, when the new model came out, but even then the situation seemed to go tolerably well until the last half-minute, if not ideally so. Yeah—that’s it: things were never quite on an even keel after they started plowing the land and enslaving animals. Most wish they hadn’t seen that part: it’s impossible to unsee, and definitely will lead to nightmares.

Now I want to take the opportunity to expand the last second or so in slow motion, since it all happened too fast to catch. To visually represent the scene, imagine an expanding city on high ground near the edge of a cliff. The city has walled off the “natural” world (all the wild beasts), who are left to occupy a broken land: a narrow shelf between the city walls and the cliff edge.

As the city expands, the wall moves out and many animals—who did nothing wrong—are pushed off the edge. I know. It’s painful to watch—but the humans inside the city are shielded from the gruesome spectacle by the wall itself. The animals “lucky” enough to remain on the ledge do whatever they can to stop the progress, propping sticks and logs against the walls, only to have them snap under immense forces far beyond their reckoning. It looks hopelessly bleak.

But hold on. A guy within the city looks at the car idling in his driveway, notices the belching emissions of CO2, has visions of warming temperatures (that part may be okay, he thinks); coastal inundation (a threat to cities, for gods’ sake!); floods and fires (homes destroyed!); climate refugees and surging immigration (not enough jobs!); mounting property damage and insurance premiums (cost of living escalates!)—in short, a serious threat to the precious economy…he decides this won’t do.

The city walls momentarily halt their outward push, as he considers this crisis. The wild creatures on the edge are still in shock, but start hooping and hollering in relief about the inexplicable reprieve. It reminds one of the trash compactor scene in Star Wars.

A New Hope

In this liminal moment, the wild creatures in the movie and the few remaining in the audience begin to imagine what the future could be. They recognize that it won’t be a simple return to past ways. That ship has sailed: no such thing as an “undo” button in the real world. But the fact that the wall’s progress hesitated means there’s hope: hope that the humans might recognize their folly. Their acid trip might end. The spell may be broken. The bucket of cold water might land on their faces. They might realize that they only make sense (and can themselves survive and thrive) in tandem with a broader community of life that also thrives. They used to all be family. They all got here together, in relationship. Why ever would they wage war? Why would they erode the very foundation upon which they depend, as all life does? They, like all creatures, need a healthy ecosphere in which to live. It’s their everlasting context.

So, visions of a new tomorrow flood the animals’ imaginations. They dream of an enlightened human, returning to be a part of the living world and not thinking themselves to be apart from it. They imagine an end to the unilateral war: an apologetic surrender accompanied by a rediscovered sense of humility and respect for all life. Yes, they still belong to the world, and the gracious world will have them back in a show of infinite forbearance. For a time, most humans thought they owned the world, but eventually came to their senses in the final moments, thank goodness.

A raccoon in the crowd shouts angrily at the screen: “What?! Crummy CO2? That’s what finally got your attention? But…okay—that’s fine. The important thing is that you eventually caught on before it’s too late. We can forgive you. Let’s just…get back to all living together by the same rules.”

Nah!

So the guy who paused at the sight of CO2—and whose concern caused the expansion to halt—has a high-tech light bulb switch on over his head, and snaps his fingers. He pushes his gasoline car into a ruinous landfill. He purchases an electric vehicle that required extensive mining, pollution, and of course more habitat destruction to manufacture. A bank of solar panels whose manufacture also involved mining, pollution, and habitat destruction plunks down onto the desert, carelessly squashing a 100-year-old tortoise (making everyone sick with indignant grief). Wind turbines that likewise came at a heavy ecological cost (but just to worthless plants and animals, right?) dot the long-lost prairies and heretofore-undeveloped ridgelines, knocking birds out of the sky. Again under full steam and a roaring economy (all that new infrastructure!), the city walls resume their expansion, as the guy in his shiny EV smiles and waves, happy that the nasty CO2 problem is no longer ruining his day or his economic outlook.

Therapy

That’s the tale. I apologize for the grim turn. But don’t shoot the messenger. The actual situation is grim, and very real. And yes, climate change is a serious player serving to make a bad situation worse, in numerous ways. I don’t want to dismiss that. But it’s one recent symptom of a much broader disease. Substituting the power source of the engine driving ecological collapse still drives ecological collapse, just without adding as much CO2 to the atmosphere. The gash in the side of the Titanic would have been no less fatal had the behemoth been powered by solar-charged batteries instead of coal-fired engines.

Before continuing, I should also point out that not all humans elected to participate in modernity. Sadly, those who refused its charms were often eradicated, assimilated, or displaced and confined by the system so that they might wither and die. Some few survive to this day living much as they did before the world went haywire, as modernity has only been 99.9% successful at stamping out the “primatives.” The point is: it’s not the whole of humanity, or universal human nature at play here. Modernity is a cancerous form of humanity that is now grossly metastatic. Can cancer cells decide they don’t want to be cancerous anymore?

We haven’t yet, as participants in modernity, collectively realized that modernity is self-terminating in a particularly ugly way that tramples irreplaceable life across the globe. We have forgotten that we, too, are animals who actually need a functioning, biodiverse ecology to  remain resilient and healthy. I keep returning to the perfectly apt metaphor (which I recently learned Paul Ehrlich has also employed in a similar context) that we are sawing off the branch on which we stand. The branch (the community of life) is incalculably precious in its own right, but also crucial to human well-being.

remain resilient and healthy. I keep returning to the perfectly apt metaphor (which I recently learned Paul Ehrlich has also employed in a similar context) that we are sawing off the branch on which we stand. The branch (the community of life) is incalculably precious in its own right, but also crucial to human well-being.

The interlude labeled A New Hope is where the positive vision resides. It’s the antidote to the grim part. We haven’t written the ending yet, and still have alternatives. Rather than double down on a failing technological approach to living in this world, we can start walking away from modernity, and figure out new ways to live. I’m not talking about a return to hunter-gatherer lifestyle: we can’t pretend all this never happened. We are changed forever. The world is changed forever. We know things we didn’t before. The future is not the past, but neither can it be a continuation or juvenile extrapolation of the present. Something big happens next, and I’d like whatever that is involve us aiming to live within Earth’s bounds, to the enduring benefit of all life (otherwise the “big” thing is the sequel described below, which I find to be less preferable). Some initial musings on constraints and possibilities appear in last week’s post.

The Sequel

The story fork that has the smiling EV-driver at the end begs for a sequel movie. That movie lasts only another second or so, if keeping to the same scale. It turns out that the destruction of the more-than-human world—and the cascading sixth mass extinction it triggers—leaves the land in ruin and unable to support humans anymore. The cliff upon which the expanding city is built crumbles and leaves modernity in ruins. Ecological resilience is so damaged that a crucial backstop has been removed. It is not easy or even possible for humans to regroup after the collapse of modernity, because they severed the branch they stood upon. The nest has been fouled; the cradle robbed. They would have been better off simplifying sooner, rather than doubling down and insisting on preserving the artificial, temporary world they created at the expense of the real, living world underneath it all.

Note 1: One way to start on a different path would be by taking a look at my reading journey, and especially Daniel Quinn’s writings. Also check out my recent podcast recommendations.

Note 2: If any reader who resonates with this story is an accomplished animator, let’s talk about working together on a funded project to bring this story to life for a broader audience.