Do the Math started out with a pair of posts about limits to growth. Galactic-Scale Energy pointed out the nonsense that results from continued growth in energy use, and Can Economic Growth Last? turned to the economic implications of stalled physical growth. This combination of topics later appeared in a dinner conversation between myself and an economist. The same pairing also evolved into chapters 1 and 2 of the textbook I wrote in 2021. And if that wasn’t enough, I published a paper in Nature Physics called Limits to Economic Growth based on the same theme. When I do podcast interviews, the hosts often want to step through this (powerful) logic.

Perhaps the result has me sounding like a broken record. It feels to me like the song “Free Bird” by Lynyrd Skynyrd. Fans will not allow the band to perform a concert without playing this classic hit. There’d be riots. I’ve had a lot to say following those two posts in 2011, and have especially taken a profound turn in the last few years. But the point remains central to our modern predicament, and until we all have it firmly planted in our heads that growth is a very temporary phase that must end, I guess I could do worse than repeating myself to new audiences—and to veterans holding up lighters.

In this post, I echo the bedrock question of whether economic growth can last with the question of whether modernity can last (see the previous post for definition and possible inevitability). Okay, nothing lasts. The whole universe is only 13.8 billion years old. The sun and the earth are only about 4.5 billion years old, and will be around in recognizable form for a comparable time into the future. Species typically hang around for millions of years. Homo sapiens is a few hundred-thousand years old. Depending on definitions, modernity has been around for at least a century or as long as 10,000 years—brief in either case, in the scheme of things. Nothing is forever, but how long might modernity last?

Whether modernity can last is perhaps a more important question than whether growth can last. The fact that growth can’t last is shocking enough for many. But it still allows mental space for maintaining our current way of life—just no longer growing. But is that even possible? I can’t be as confident in my answer as I am for growth, since the question of growth comes down to incontrovertible concepts and, well, math. Still, I strongly suspect the answer to this new question is “no” as well, and in this post I’ll expound on my misgivings.

[Note: I had another post in 2021 enumerating reasons to worry about collapse, which is a relevant but—I would say—less enlightened precursor to this piece. Since then, I have become aware of the important role of human supremacy, the materials difficulties associated with renewable energy, the crushing numbers on loss of biodiversity, and have released my anxious grasp on modernity—having better appreciated the more-than-human world and our role within the greater community of life.]

Growth

We start on familiar ground. I won’t rehash the arguments, as the first paragraph provides an over-abundance of links to material on this topic. For the purposes of this post, I will just restate that growth has been a centuries-long trend, such that our energy/materials use, economic systems, political systems, social safety net systems, labor and retirement systems, and even mental frameworks have become predicated on growth. I still routinely encounter surprise and push-back to the simple and obvious statement that growth isn’t forever.

For something that is necessarily a temporary phase, we have surely dug our claws deep and will have great difficulty letting go, as I think we must eventually do. I picture a cat shooting up a tree in fantastic form (the easy direction, given claws), but then getting to a great height and having no obvious graceful way down. This is what fire departments were created to handle (maybe the thick coats are more about claws than flames?). Can we call a fire department to rescue us from modernity’s precarious and embarrassing position?

While adjusting to a life without growth would constitute a monumental challenge, requiring major overhauls—or abandonment—of many institutions, it is at least attractive to ponder steady-state approaches to life on Earth, and many have explored this space. But can we really stay up in the tree? Another useful metaphor compares the challenge of converting an airplane—which must keep moving forward to stay aloft—to a helicopter, which can hover…and effecting the conversion in mid-flight (i.e., without crashing). It’s not clear how this would come off.

To the extent that modernity depends on growth—an open question but with no evidence to support the contrary—then modernity cannot last. But let’s not give up just yet.

Energy and Fossil Fuels

Energy has been fundamental to our story of growth. The various hockey stick curves over the last century or so are a reflection of energy and population. What’s more, human population itself is a reflection of energy, as mechanized, fertilized agriculture was made possible by fossil fuels. Since energy per capita has also increased like a hockey stick, the ecological impact (and many other metrics like GDP) takes on the shape of a super-exponential (still resembling a hockey stick on a logarithmic plot).

Energy is not the only factor in promoting growth. I would put ecological exploitation at least as high (though effected via energy), then materials, then innovation. That’s right: innovation amounts to very little without a biophysical basis to exploit. It’s rather typical of a human supremacist culture to elevate innovation to the top of the heap. But (temporary) explosive biophysical growth is also possible in natural systems given adequate energy and atoms without one iota of human innovation.

Energy provides the motive force behind our exploits. Prior to fossil fuels, we still saw a much slower version of growth as we harnessed wind for global trade, wind and water for milling and mechanization, and gobs of solar energy in the form of crops to feed animal and human labor. No energy, no growth. No grain, no pyramids.

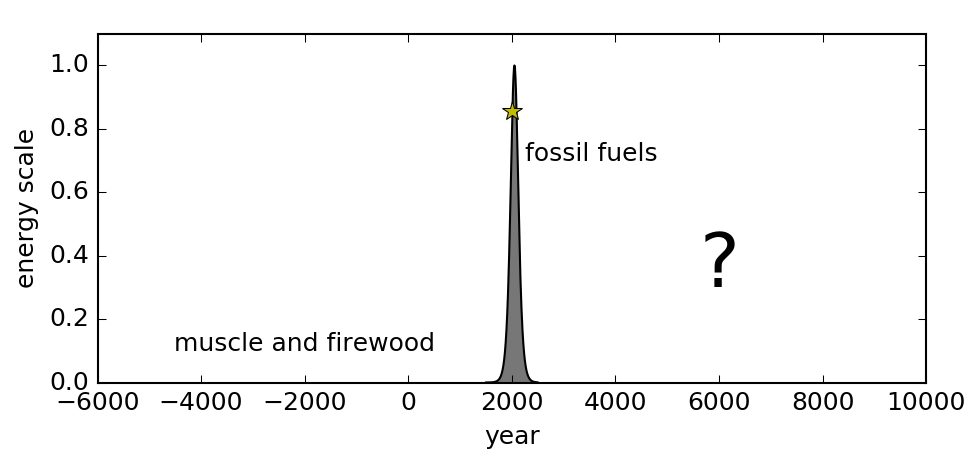

Fossil fuels represent such an overwhelming contribution to modernity that it is really hard to conceptualize its continuing without them. I return to a familiar plot.

Until fossil fuels, human utilization of energy was tiny and in the form of human/animal labor and firewood. Fossil fuels will necessarily be a transient affair. Is the future a reversion to past ways, or something different? We can’t say.

The fossil fuel spike, or carbon pulse, is a lonely landmark in the temporal landscape. What a strange spectacle! Imagine the Washington Monument but without any other large structures all the way to the horizon. The left-hand side of the spike is what all these hockey stick curves reflect. We know that fossil fuel usage will also have a right-hand side that drops back to zero—simply because it’s a finite resource that does not permit us to draw it in some arbitrary way: the area under the curve is set and not subject to our imaginations.

Now, the modernity booster would say that we can’t see the future, and that just because the horizon to the west is clear, the eastern view may yet have all sorts of unfathomable marvels in store. It’s not that I lack the imagination or can’t appreciate the appeal of a fantastical future. I get it. I still remember how it felt to experience the magic of Christmas (what a swell fellow, that Santa Claus), imagine myself building a rocket-powered bicycle, and even as late as 16 years old thinking that if friction were low enough, my telescope might track the stars with no motor, just by inertia. Then I learned heaps of math and physics and built a lot of very real things: cutting-edge first-of-its-kind devices that successfully did new things. I now feel much more grounded and better-calibrated to the line between realistic and fantastical. In some ways, my imaginative skills have advanced well beyond the usual unhinged realm to a richer, more constrained and complex space. The easy part is imagining the one way something might go right—it’s a much bigger challenge to conjure the myriad possible failure modes. I am no longer very impressed by the more pervasive, facile sort of imagination (one might say that this garden variety imagination lacks imagination).

In the foregoing case, my analysis of limits to growth rules out the “unfathomable marvels” on the energy front on thermodynamic grounds. At least, such marvels won’t subvert limits and allow unabated growth. But now I’m beating a dead horse and have worked my way back to the previous section.

I will not go so far as to say that we will never have a source of energy that is not part of the standard mix today, like fusion, for instance. Although, I think this to be unlikely for a variety of reasons—primarily because other factors intervene and dial down our capabilities before such a thing comes to fruition—not to mention an impractical degree of complexity in a scheme that only boils water to make electricity. Nor would I say that the energy mix won’t evolve to higher fractions from renewables as fossil fuels wane: this is already starting to happen, very slowly and at small scale. But I would seriously question our ability to preserve what we call modernity without fossil fuels. Not only do we lack demonstration anywhere in the world of a fossil-free modern society, we also have no clear paths to mine, manufacture, transport, and feed at today’s scale without fossil fuels. For instance, we have not built renewable technologies without substantial assistance from fossil fuels. Modernity rose to its current magnificence on the back of fossil fuels, and could very well ride the pulse back to zero. Live by the sword, die by the sword.

But energy alone is not a conclusive case. One might argue that it would indeed be difficult to maintain our present scale—8 billion people at a high-energy standard of living—but that some scaled-down version of modernity is not ruled out under renewable energy, for instance. Or maybe we could live the lifestyle of 1750: no fossil fuels, but still “modern” in a number of ways. I will return to this point.

The last thing I’ll say about energy foreshadows the ecology section. The question is: what have we used energy to do? We have used it to expand the human enterprise and population, knock down forests, destroy and fragment habitats, drive extinctions, and generally threaten the vitality of the planet. To me, “solving” the energy problem as fossil fuels give out is pretty frightening: how would it not simply perpetuate the ecological nosedive we have initiated? Only if we put ecological concerns above energy do we stand any chance of survival.

In summary, energy:

- is fundamental to modernity;

- is responsible for the human population surge and other hockey sticks;

- cannot continue increasing into the future;

- has been utterly dominated by a temporary spike of fossil energy;

- may not permit modernity’s continuance in non-fossil form;

- powers ecological devastation, independent of its source.

Materials and Recycling

Connecting to the energy side is another set of physical considerations. Besides our reliance on energy, we rely on atoms. Atoms are not all the same flavor and are not of infinite variety—nor are their practical combinations (compounds). Their supply is finite on the planet, and the energy required to access and process them limits what we can expect to do in utilizing them.

Materials for Renewable Energy

The interaction between energy and materials is fundamental. Solar energy means nothing to us until it interacts with matter, for instance. This becomes apparent when assessing the material demands of renewable energy. Because solar and wind are diffuse, low-intensity energy flows, a lot of “stuff” is required to harness their energy. Table 10.4 of the Department of Energy’s Quadrennial Report illustrates that renewable energy technologies require an order-of-magnitude more materials than fossil fuels for generating the same amount of electrical energy (not including the fossil fuel material itself, which is considerable). Setting aside the fact that we rely on fossil fuels for material extraction and processing, this means that replacing our fossil fuel habit with renewable energy would require a substantial increase in material extraction (mining, scraping) on the planet—translating to more deforestation, more habitat loss, more pollution (tailings), more processing, and more extinctions.

The DoE table indicates that each terawatt-hour (TWh) of solar energy needs 850 tons of copper. Replacing the global 15 TW fossil fuel appetite (given 8760 hours in a year) translates to a need for 112 megatons of copper (per year), which is 5.6 times current global copper production. We can’t get there by recycling, because all those solar panels do not exist yet, so a massive build-out would require a massive increase in mining. And copper is just one of the many material requirements of solar panels. The push for solar is motivated primarily by climate change concerns, driven by CO2 emissions into the atmosphere. Thus, we might say that the burning of fossil fuels represents an assault on the air. Switching to renewables would move the war to an all-out (well, intensified) assault on the land—and thus on the community of life that depends on the health of the land.

What’s more, the material requirements are a function of lifetime energy (not power) delivered, meaning a continuous materials demand going forward, if aiming to preserve the status quo. In practical terms, a solar panel or wind turbine delivers a finite amount of energy before it ages and needs replacement. Perhaps this is 20–40 years, but it’s not indefinite. Then you need the materials all over again, so the ground assault continues. Sure, recycling could ease the pain, after the initial build-out. But let’s not be cavalier about the recycling concept. This is not a playground game of tag, whereby uttering the word “recycling” means you’ve touched base and are no longer vulnerable.

If the apparatus delivers useful energy over a lifetime of 25 years, for instance, then the initial build-out of a full-scale replacement of fossil fuels will require about 250 times the materials currently required annually to support fossil fuel energy delivery (roughly 10 times the material demand over 25 years).

Similarly, because global copper production would need a roughly 6× boost in the case of solar replacement, we’re talking about 150 years of current global copper production before completing the initial build-out. Only after the first-generation lifetime is up can recycling start to play a role (decades later). Do we even have that much viable ore?

Besides the vast absolute amount of material required, material extraction rate is another factor. Taking a slow 50 years to complete the project still requires a 3× boost in annual production. A more impatient 10 year plan requires copper mining at 15× the current rate. Is either option even remotely possible? Trends in solar and wind development over the last decade—perceived as rapid and encouraging—would take a few hundred years to reach our present total energy appetite, for reference.

I should note that the energy-based material calculation in the original table assumed a lifetime for the facility, which may be off in either direction. But since we’re talking about an order-of-magnitude increase in material per unit of energy delivered, even a factor of two error in the lifetime estimate is not a game-changer.

Recycling Renewables

Now, on the recycling front, we never expect to get 100% return in recycling. Even getting 90% of the copper out of all the solar panels ever built would be a feat. This would mean that to keep the infrastructure up, we’d need to source 10% of the material from the ground on a continuing basis. Since solar replacement demands a 6× increase in copper, a steady 10% “new” replacement means a continuous 0.6× increase, or a 60% increase over current practices. So, after extracting at 6× the present pace for a few decades, we could settle down to 1.6× the current pace for the indefinite long haul.

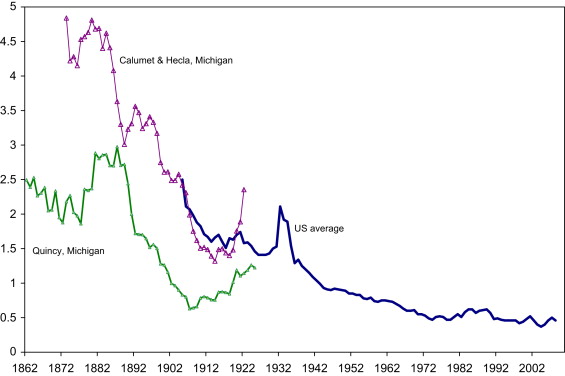

Copper production today is causing ecological harm in the form of 200× the volume of tailings and the pollution associated with processing the ore. Ramping up at any level is very worrisome. Moreover, the low-hanging fruit is gone, so that copper ore is already an order-of-magnitude poorer concentration than it used to be, and that gets only worse if we grab a few centuries’ worth of copper for a solar build-out. It is essentially like fast-forwarding the ore concentration plot (below) to 150 years in the future. Is copper mining even viable at that point?

From Crowson (2012).

It needs to be understood that renewable energy is not actually about saving the planet: clearly it will ravage more land and habitats in pursuit of materials. It’s really about preserving modernity in the face of CO2. Let’s be clear on the goal, here, and how ultimately narrow/misguided it is. Which is more valuable—modernity or the ecological health of the planet? Which depends on which?

Recycling More Generally

Specific cases aside, we can make a more general statement about materials. Modernity is very dependent on metals. Sophisticated electronic devices routinely employ 40 or so metals from the Periodic Table. Meanwhile, recycling recovery is never complete. For consumer goods it can be quite low. The metals in electronic devices can be so dispersed as to render recycling non-viable (requiring ever-more energy, for one thing). And, of course, as soon as one critical component fails (or even well before), we tend to replace the entire device in our current schemes.

But let’s ignore the abysmally low recapture rates of the real world at present and dream of achieving 90% recovery of some element we’ll call randomonium. Multiply 0.9 by itself a number of times and see how long it takes to get to 10% of the original (0.1). I’ll take the math shortcut and say the number of generations is N = log(0.1)/log(0.9) (any log base will do). After 22 cycles, the original resource is down below 10%. Depending on the use case, cycle time may be rapid or long. So it could be down to 10% in a few decades or a few centuries. Either way, the modernity beast is slowly starved of previously-mined metals on a timescale that is not terribly long. As this happens, my guess is that technological capability wanes and recovery fraction declines as well—only speeding up the de-metalling process. Remember that many other things may be happening in tandem: fossil fuel scarcity, ecological harm, climate change, crop failures, famine, social unrest. We don’t have the luxury of isolating problems into tidy, solvable domains. It’s a predicament.

Before knocking recycling entirely, we could point out that 90% recovery might allow us to reduce primary extraction down to 10% of its present scale and hold on indefinitely. Is that possible? What would it mean? For perspective, I would say that the scale of mining in the last 50 years has been ecologically devastating: producing a trend line that shows far more ecological loss than gain. Maybe we could survive 100 years at the current intensity, if that, before the ecosphere could no longer assimilate the costs. A reduction to 10% scale might then extend the timeline to 1,000 years. That is still short on civilization timescales, and also assumes “magical” 90% recycling efficacy.

As with energy, material limits alone do not preclude modernity’s continuance, but the warning signs are up. It’s not at all clear that the low-hanging inheritance we are now rapidly spending will sustain us for centuries more in anything like the present mode.

Biodiversity and Ecological Vitality

To me, this is the non-negotiable element. Humans are one of many species on a planet that has developed a complex web of interdependent life. We have barely scratched the surface in understanding the connections and cooperations in the living world, and likely never will have a full grasp (which would suggest it’s not a legitimate goal, anyway). We therefore depend on the health of countless other species in ways that we do not fathom.

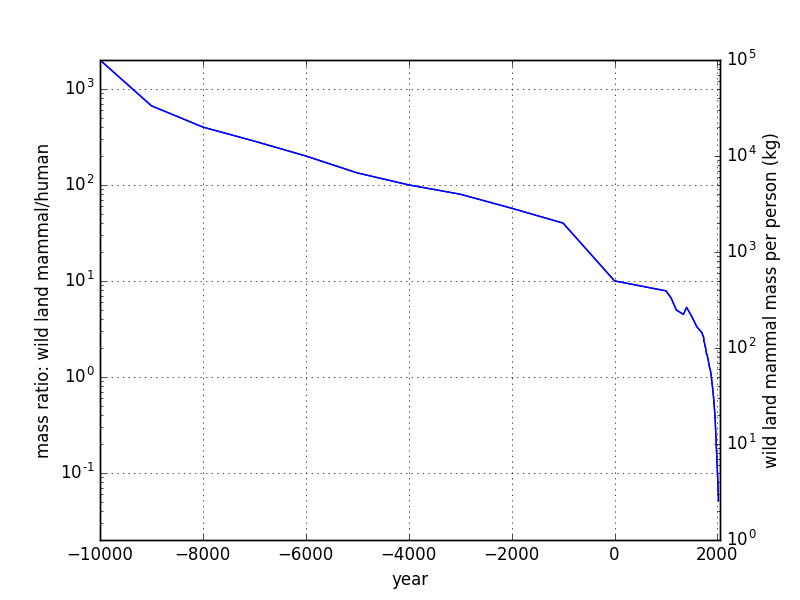

Meanwhile, the trends are alarming. Extinction rates are roughly 1,000 times higher than background rates. The average decline in over 20,000 vertebrate populations spanning thousands of species is about 70% since 1970. Wild land mammal mass is down to 20% of its pre-modernity level, to the point where only 2.5 kg of land mammal mass exists in the wild for every human on the planet. The associated plot (below) induces pants-wetting alarm. It’s a cliff edge, and forces us to wonder how modernity could possibly be the correct path.

Mass ratio (left axis) and total mass (right axis) of wild land mammal mass per person on the planet.

The dots are not difficult to connect: deforestation, habitat destruction and fragmentation, overhunting and overfishing, “pest” elimination, climate change, humans outcompeting other life for food, pollution of streams and landscapes, microplastics, and, and, and. All these things contribute to declining animal populations on a march toward extinction, and I should stress that it’s not dominated by CO2, so renewable energy doesn’t fix it. At what point will the fabric of life be too torn to maintain its integrity? Almost like the fashion statement of numerous rips in the legs of jeans, pretty soon we’ll no longer be wearing pants.

Put simply, modernity has come at the expense of ecological health and the vitality of the community of life. It is not at all clear if modernity can exist any other way. Modernity could very well be a self-terminating prospect for exactly this reason, as humans can’t survive without a functioning ecosphere. Right now, the ecosphere is gasping for breath. I would say that it’s on life support, or in the ICU. But no—that would imply concern and remedial action. It’s just bleeding out in a ditch as we motor past, largely oblivious to its condition as we inflict even more damage.

Philosophical Underpinning

This brings me to a foundational concern. I would claim that the philosophy upon which modernity is built is fundamentally incompatible with its own longevity: a fatal flaw in the operating system. At its center is the notion that humans are the apex species, rulers of the planet, increasingly in control of our own destiny and the world around us, on our way to becoming godlike masters of the world—and galaxy/universe among the more imagination-challenged. I lump this all into what I think is best characterized as a human supremacist culture.

Could we, however, dial lifestyles back to a nearly-modern 1750 mode? Or could we find long-term success in a reduction to, say, 100 million affluent humans living modern standards? Maybe we could dilute the “bad” by simply having less of it. In these scenarios, I can’t get past the rotten philosophical foundation. I doubt that a human supremacist culture would limit its bad self in this way and keep itself there. To do so would require putting non-human concerns first. The entire 10,000 year lineage of modernity has held expansionist, exploitative beliefs centered on humans. Those who have rejected such beliefs lived in ways alien to modernity. The ontological basis for modernity is the engine that produces incompatibility. Unless the dynamical foundation changes, why would we expect a different result?

Any system that puts short-term human concerns above all else—to the exclusion and detriment of the community of life—will surely fail, taking many species down with it.

Maybe all species put themselves first (though many are engaged in complex cooperative arrangements in reciprocity and a spirit of giving—think about plants). But humans have both tremendous capabilities and—presently—a human supremacist attitude. A slug might well be slug-supremacist, but does not possess the capability to create a sixth mass extinction (or annihilate virtually all life in the blink of an eye via nuclear Armageddon). The combination of capabilities and supremacy is the losing ticket. Human capabilities include intelligence, dexterity, flexible diet, and climate versatility. Those are hard-wired in our DNA and are unlikely to change. So we must do something about the supremacist culture. It’s the only strategy that offers survival to us and to countless other species.

A human supremacist—not driven by hate, let’s be clear—thinks nothing of clearing a forest for crops; exterminating pests; enslaving animals for work or food; damming a river for energy; killing a bear who has attacked a human; animal research for the remote possibility of someday treating a human disease; scraping the ocean floor for minerals; destroying desert communities of life with solar installations; killing countless birds with domestic cats, speeding hulks (planes, cars, windmills), and even house windows. Why ever wouldn’t we do these things? One human life (especially a child) is worth any number of frogs, eels, meerkats, chickadees, or deer, in the human supremacist mind—a point I’ll revisit in a future post.

To me, it is this attitude that defines modernity more than anything else. It is this mythology that encourages us to seek ultimate mastery by exploiting as much as we can; using whatever food we can find or grow, whatever energy we can harness, whatever materials we can scrape, at the expense of any other species or community of life. I suspect that without this attitude, we would not live a high-energy technologically-oriented life, or even practice grain agriculture—based on the fact that cultures who maintained humility in relation to the community of life did not embrace these practices, only to be overrun by those who did. Modernity would seem (so far) to require putting humans first, at any cost.

An article by Robin Wall Kimmerer that appeared last week in the New York Times echos this theme and the core importance of philosophy (worldview), saying:

We need more than policy change; we need a change in worldview, from the fiction of human exceptionalism to the reality of our kinship and reciprocity with the living world. The Earth asks that we renounce a culture of endless taking so that the world can continue.

She is more polite (effective) than I am, using exceptionalism rather than supremacism (which is how I started out, too).

A Workable Path

The longevity of our species ultimately depends on the longevity of the broader community of life. Since humans have developed the capability to quickly destroy ecological health, tearing the community of life to shreds, we come to the conclusion that this behavior is not in our species’ own best self-interest. Modernity puts us on the path of destruction, while markets lash the steering wheel in place. All the “goods” we can readily identify from modernity are just one side of a coin whose back-side ills cannot be sliced or wished away. The only way to a better path, as I see it, is to demote humans. Eliminate human supremacist cultural values (the Human Reich, as Eileen Crist calls it in a brilliant piece). Put the community of life first. Trade hubris for humility. Live in service to and in reciprocity with the more-than-human world. If this means the end of gadgets or other unsustainable perks, so be it. What’s more important?

I don’t know for sure what a successful long future looks like, beyond likely following the broad tenets in the previous paragraph. I know that many Indigenous cultures embodied such humility (and still do, in small numbers). So I know that mode can work for long stretches of time, but I suspect it’s not the only one that could. I’m fairly sure that whatever range of viable possibilities exist, they would be essentially unrecognizable to practitioners of modernity. Therefore, I am tempted to call it: modernity is incapable of “correct” relationship with the community of life, and therefore terminal. I think modernity cannot last. Whatever comes after, it looks too different to call it modernity. I personally suspect it is low-tech (low energy; low metallicity; local communities rather than global), but who knows? Certainty in these matters deserves suspicion.

We will likely shed more than a few tears at modernity’s passing, and that’s understandable. But joy awaits as well. Just remember, and I’m speaking directly to you here: you are not modernity! You need not die with it. You’re bigger than modernity. You’re more lasting. You’re more complex. You’re more versatile. You’re only booking passage in the modernity boat, but are not committed to going down with it. If you find joy in modernity, I suggest building joy in other ways: nature, family, community, life; not in money, job, gadgets, and stuff. Try to get yourself to a place where you rely less on modernity—even just emotionally—so that if it fades out in your lifetime you won’t be devastated or paralyzed. It also helps to expand the definition of “we” to include the entire community of life: plants and animals as our older brothers and sisters on the planet (upcoming post). What makes us all happy, collectively? Modernity is not the answer.

[Note: the initial version of this post used invalid shortcuts in interpreting the DoE materials numbers, resulting in a ten-fold rather than six-fold copper increase. This and related numbers have been corrected.]