A UK government auction has secured just 3.7 gigawatts (GW) of new renewable capacity – only a third of the total last year – and failed to contract any new offshore wind.

The 95 projects winning “contracts for difference” (CfD) from the government are expected to generate around 9 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity, less than 3% of current UK demand. This is 82% lower than last year’s auction, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

The “extremely disappointing” result follows massive supply chain and inflationary pressures on wind and solar, estimated to have pushed the cost of offshore wind up by as much as 40% since last year.

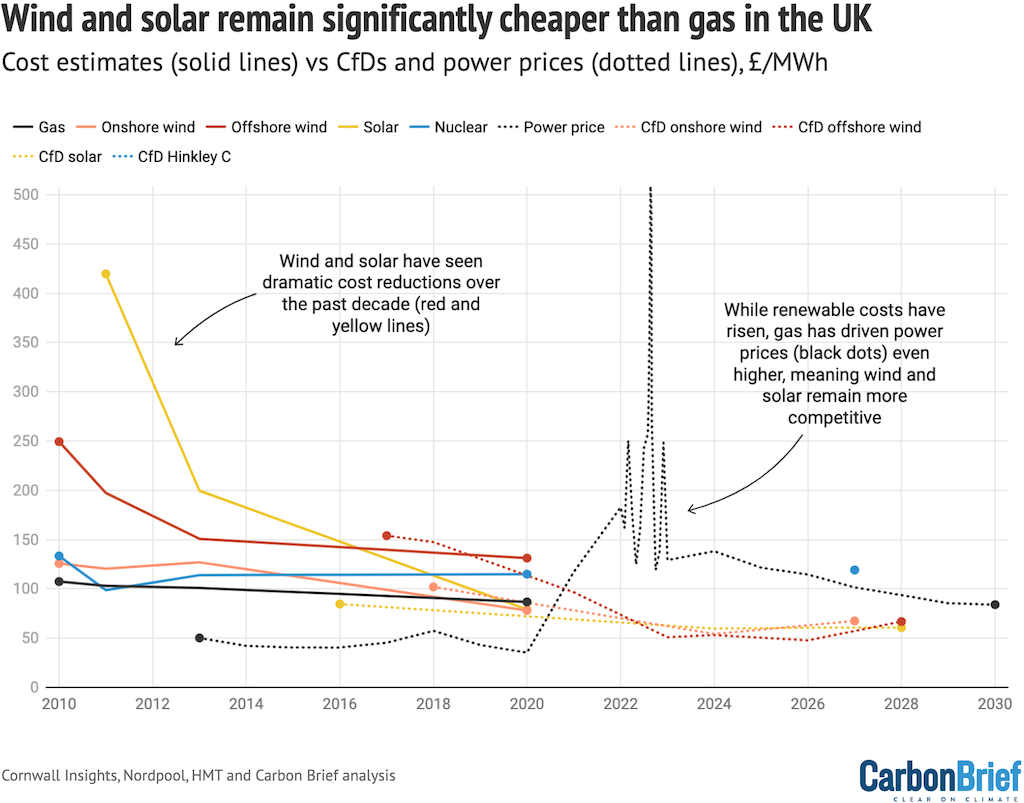

Yet wind and solar remain the cheapest way to generate electricity in the UK. This is because gas prices are around 100% higher than they were before the global energy crisis and are expected to remain elevated for the foreseeable future.

The result is being seen as a threat to the government’s targets for 50GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030 and a fully decarbonised grid by 2035.

These targets are key enablers of the UK’s legally binding carbon budgets. If they are to be met, subsequent auctions will need to deliver much more capacity than was secured this year.

Below, Carbon Brief explains the auction results – and looks at what happens next.

Smallest auction return since 2015

The UK government has committed to getting 95% of the country’s electricity from low-carbon sources by 2030 and to fully decarbonise the grid by 2035. It is also aiming for “up to” 50GW of offshore wind by 2030, including “up to” 5GW from floating offshore schemes.

The government continues to describe offshore wind as “central” to meeting its targets and has previously been keen to tout the UK’s “world-leading” status for the technology.

In March, the government released a glossy “offshore wind net-zero investment roadmap”, in which then-secretary of state Grant Shapps said: “[W]e are cementing our position as amongst the most attractive places in the world for investing in offshore wind.”

Shapps wrote of the need for a shift to low-carbon supplies in the face of the global energy crisis and Russia’s war in Ukraine, to “break[] with the fossil fuels that powered our last two centuries”.

Yet today’s auction failed to secure any new offshore wind projects.

One wind industry insider tells Carbon Brief: “How embarrassing to claim to be world leading and not have anyone bid into your auction.”

CfD auctions for new renewable capacity are the UK’s primary route for achieving its targets in the electricity sector. Today’s fifth auction (AR5) follows the first auction round in 2015, second in 2017, third in 2019 and fourth in 2022. Further rounds are due to be held annually.

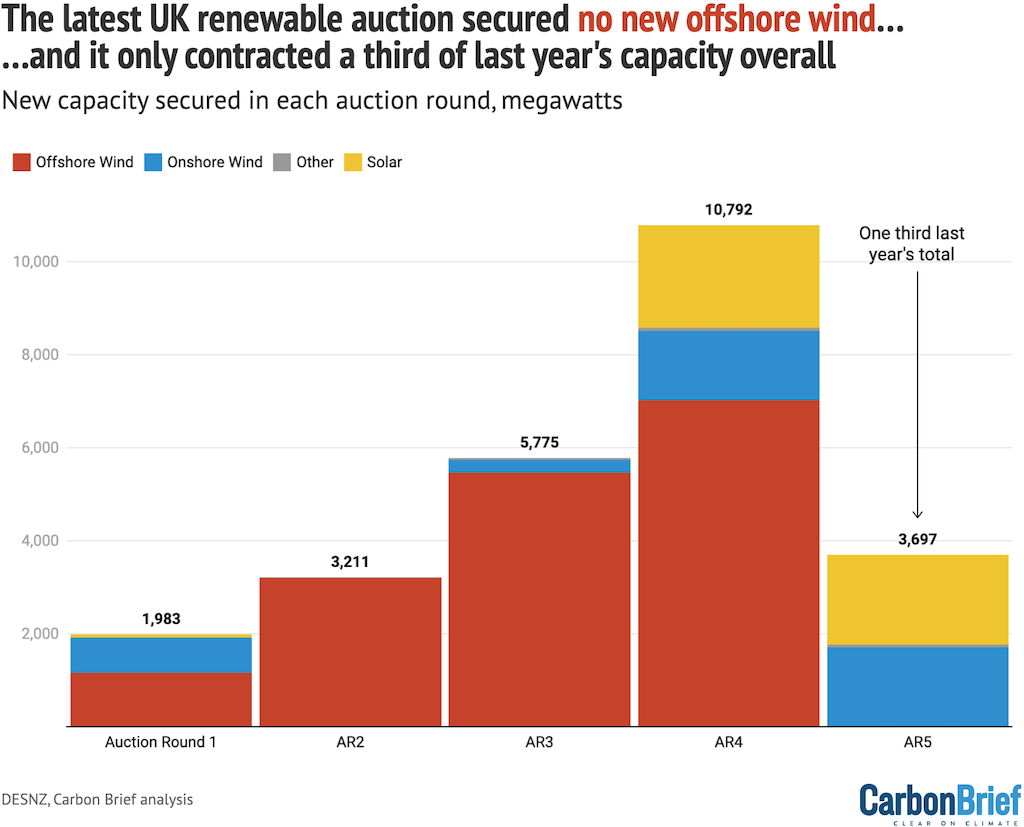

The latest round secured just 3.7GW of new capacity – chiefly solar (1.9GW) and onshore wind (1.7GW) – as shown in the figure below. As well as failing to secure any new offshore wind for the first time since the CfD auctions began, the round only contracted one third of last year’s total.

New capacity secured in each CfD auction round to date, megawatts, broken down by technology type. Source: Department for energy security and net-zero, Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Simon Evans for Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

In addition to onshore wind and solar, the auction also secured a small amount of tidal projects (53 megawatts, MW) and, for the first time, geothermal (12MW).

In its press release marking the auction results, the government highlights that the number of projects contracted this year is larger than in any other round.

Nevertheless, Carbon Brief analysis shows the winning bids are expected to generate just 9 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity when built, equivalent to less than 3% of current UK demand.

This makes the latest auction the smallest since 2015 in terms of the electricity it will generate, coming in some 82% lower than the 47TWh secured last year, as shown below.

(In total, the projects contracted under all five auction rounds would generate 105TWh of electricity when they have all been built. This is roughly a third of current UK demand.)

Electricity generation from renewable projects secured in each of the UK’s five CfD auction rounds, terawatt hours, broken down by technology. Source: Department for energy security and net-zero, Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Simon Evans for Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

Generating the same amount of electricity as secured in the latest auction using gas-fired power plants would require around 18TWh of the fuel.

This is equivalent to the amount of gas that would be produced by issuing new North Sea licences, which the opposition Labour Party has pledged to block if elected at the next election.

Similarly, the 105TWh of electricity from all five auctions will displace about 210TWh of gas. This means UK net gas imports in 2030 would have been around 50% higher without the CfD scheme.

If the latest auction had secured any new offshore wind, each 1GW of capacity would have generated around 5.5TWh of electricity, displacing 11TWh of gas demand.

No new offshore wind

The lack of offshore wind in AR5 follows warnings from industry throughout 2023 that cost pressures would limit its ability to bid at the record low prices seen in recent years.

Trade body Energy UK noted earlier this year that inflation, interest rates increases, a supply chain crunch and regulatory uncertainty around grid connections and planning had all pushed up overall costs of offshore wind projects,

The government was aware of the pressures upon offshore wind costs and, in August, it increased the CfD budget by £22m overall. The budget for established technologies including offshore wind as well as onshore wind and solar increased from £170m to £190m.

But this did not go far enough, with Energy UK noting that there were “significant concerns” that the auction parameters did not “recognise the scale of cost increases seen over recent months”.

The administrative strike price (ASP) for offshore wind was set at £44/MWh, a small increase on the £37.35 price which offshore wind cleared at last year. This is below current electricity prices, which across August were £82.19/MWh on average, according to Nordpool.

According to the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) the cost of offshore wind has increased by as much as 40% over the past year due largely to inflation.

In terms of tonnes per MW, steel accounts for 90% of offshore wind, according to international trade association Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). Over 2020 and 2021, however, steel prices increased by 50%, according to a report from the council.

This further increased through 2022 due to the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in particular on surging power prices. For example, British Steel lifted its prices by a “record 25%” in March 2022 due to rising electricity costs.

The offshore wind industry also depends on copper for cabling and electrics. However, the price of copper increased by 60% over the two years from 2020, notes GWEC.

Other core components have also increased in cost. Analysis by Energy Monitor published in April suggests that the average cost of a 1MW wind turbine has increased 38% in two years. From $0.86m in 2020 to $1.18m in 2022.

The most significant minerals used to make a wind turbine are copper, zinc, manganese, chromium, nickel, molybdenum and rare earths. These have all increased in price since 2020, with the price of molybdenum, in particular, surging by 285%, according to Energy Monitor.

Overall, these seven metals have increased in price by over 93%, the article notes.

The impact of these rising prices has already been felt in the offshore industry, with Swedish energy group Vattenfall announcing in July that it was stopping the development of its Norfolk Boreas windfarm, which won a contract in last year’s auction.

The company said “higher inflation and capital costs are affecting the entire energy sector, but the geopolitical situation has made offshore wind and its supply chain particularly vulnerable”.

Beyond cost increases, policy changes have also contributed to offshore wind challenges. The latest round was the first two-pot auction, with solar and onshore wind both directly in competition with offshore wind.

The government also removed the “merchant nose” opportunity, which had allowed companies to delay triggering their CfD contract in order to benefit from high power prices.

For example, the Moray East offshore wind farm delayed the CfD contract it won in 2017, at a strike price of £57.50/MWh in 2022, to allow it to benefit from higher power prices seen at the time.

The Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) called on companies to act “fairly” and subsequently consulted on the exclusion of the merchant nose opportunity.

For AR5, there are set parameters for determining when a project has begun operation and the CfD takes effect.

During the consultation on the merchant-nose opportunity, industry noted that removing it could add significant risk to their business plans.

This could make “securing finance more difficult or more costly at a time of more general market volatility and uncertainty for the industry, and may make the UK market less attractive for investment”, industry suggested within the consultation.

Cheaper than gas

While renewables have been hit by significant supply chain and inflationary cost pressures since last year’s auction, they remain the UK’s cheapest way to source new electricity generation.

Indeed, while industry estimates suggest the cost of offshore wind might have climbed by 20-40% (see above), a major cause is the global energy crisis triggered by surging fossil fuel prices.

After years of rapid cost reductions for wind and solar, this year’s auction saw the “strike price” of winning onshore wind bids rise by around a quarter, while solar bids were essentially unchanged.

In parts of 2022, UK wholesale gas prices surged more than 10-fold. This saw the winning bids in last year’s CfD auction coming in some nine times cheaper than gas power in August last year.

While gas prices have since settled down, they remain roughly double their level before the crisis – in other words, a 100% increase – as shown by the dotted black line in the figure below. (This dotted line shows power prices, which are a reasonable proxy for the cost of gas power.)

This means renewables are and will remain significantly cheaper than gas. This would also have been true for offshore wind, even if prices had risen by 40%, indicated by the final red dot.

Government estimates of the levelised cost of energy (LCOE) from various technologies (solid lines) versus CfD strike prices and power prices (dashed lines). Figures are all in £(2023) per megawatt hour (MWh) of electricity, plotted against the year of delivery. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of government cost projections published in 2010, 2011, 2011, 2013, 2016 and 2020 and CfD auction results from 2015, 2017, 2019, 2022 and 2023, with all prices adjusted to £2023 using the Treasury deflator. Past power prices are weekly, monthly or yearly average day-ahead prices from Nordpool and forecast annual average prices are from Cornwall Insight. Chart by Simon Evans for Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

EU consumers are estimated to have saved €100bn due to wind and solar projects newly installed during 2021-2023, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The global power sector saved $520bn in 2022 thanks to already installed renewables, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). It noted that the competitiveness of renewables increased, despite cost inflation, because fossil fuel prices rose even further.

The agency said in an August release:

“IRENA’s report concludes that expected high fossil fuel prices will cement the structural shift that has seen renewable power generation become the least-cost source of new generation, even undercutting existing fossil fuel generators. Renewables can protect consumers from fossil fuel price shocks, avoid physical supply shortages and enhance energy security.”

Moreover, as shown in the chart above, UK gas prices – which generally set the price of power overall – are expected to remain high for much of the 2020s.

The wholesale price of electricity is expected to remain at current elevated levels for several years. The latest forecast from consultancy Cornwall Energy has power prices topping £120 per megawatt hour (MWh) until 2025, falling slowly below £100/MWh in the years to 2030 as larger volumes of renewables start to eat into the running hours for gas.

High gas prices for years to come mean consumers could have saved around £180m a year for each 1GW of offshore wind secured in today’s auction, according to thinktank the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU), even with project costs rising 20-40%. A similar estimate from Energy UK puts the saving at around £100m in 2030, for each 1GW of offshore wind secured.

In a statement responding to the auction result, trade group RenewableUK says:

“In this auction round for clean power contracts, up to 5GW of offshore wind was eligible to compete which could have powered nearly 8m homes a year and saved consumers £2bn a year compared to the cost of electricity from gas – a £24 annual saving on an average household bill. However, offshore wind projects did not bid into the auction as a result of the maximum price being set too low.”

(Note that while the amount of electricity generated by wind and solar farms is variable, necessitating grid flexibility and long-term energy storage to ensure security of supply, they remain the most competitive technologies to decarbonise UK electricity supplies, according to the government and most other analysts. The government’s advisory Climate Change Committee puts the costs of integrating wind and solar into the grid at £10-20/MWh.)

Targets at risk

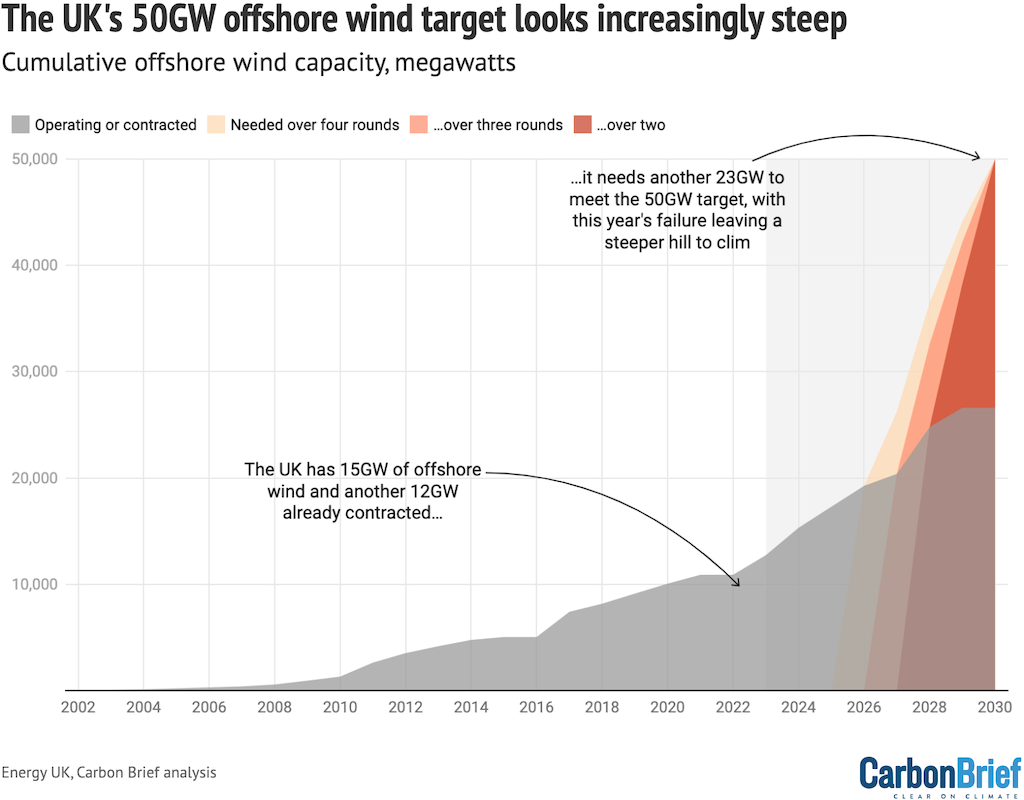

The failure to secure any new offshore wind in the latest auction round means the UK’s “50GW by 2030” target for the technology looks increasingly remote.

The UK’s current offshore wind capacity stands at 15GW, according to industry body Renewable UK. A further 12GW is in the pipeline – though at least one of the projects within this total has been suspended due to inflationary cost pressures. This means the UK would need to secure another 23GW of offshore wind capacity to hit its 2030 target of 50GW.

Auctions are now held annually, but winning projects still take several years to build.

The fourth auction round announced results in August 2022 and the offshore wind projects it contracted will not come online until 2026 at the earliest – around four years later.

This implies that the capacity needed to hit the 50GW target would need to be contracted by 2026 at the latest – meaning the next three auctions would need to secure nearly 8GW each.

A more conservative analysis from Energy UK suggested the necessary capacity would all need to be contracted by 2025, leaving only two auctions to secure nearly 12GW each.

For comparison, last year’s fourth round secured 7GW of capacity.

The UK’s current and contracted offshore wind capacity (grey area) and the increasingly steep curve to hit the 50GW target following this year’s auction result is shown in the figure below.

The yellow curve indicates the pace of growth that would have been needed if the UK had secured 6GW of capacity this year and in the next three auctions, with projects being delivered four years after contracts are signed. The pink and red curves show how this trajectory is squeezed if the target has to be met over just three or two auction rounds, respectively.

Cumulative operating or contracted UK offshore wind capacity (grey area), gigawatts (GW), and the trajectory to meeting the “50GW by 2030” target over the course of four auction rounds starting from 2023 (yellow), three auction rounds (pink) or two rounds (red). Source: Energy UK and Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Simon Evans for Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

Adam Bell, director of policy at consultancy Stonehaven and a former senior energy official tells Carbon Brief the UK could still “just about do it”, but only if the government “pulled out all the stops” in areas including rapid reforms to the offshore wind planning and consenting regimes.

He adds: “I see no indication we’d make such a radical change in time.”

With offshore wind due to form the backbone of the UK’s net-zero electricity system, the failure to secure new capacity in the latest auction also puts the government’s 2035 target to decarbonise the electricity system – and its wider, legally binding carbon budgets – at risk.

In an emailed statement, Greenpeace UK policy director Dr Doug Parr says:

“Thanks to cost pressures and inept government policy, this auction round has completely flopped – denying billpayers access to cheap, clean energy and putting the UK’s legally binding target of decarbonising power by 2035 in greater jeopardy. It leaves the UK more dependent on expensive, imported fossil gas.”

RenewableUK says in a statement:

“Industry is warning that the failure to secure any new offshore wind capacity risks putting our energy security and net-zero targets at risk, keeping the UK dependent on fossil fuels for longer…National Grid forecasts that – regardless of progress on other renewables and nuclear – we will need at least 73GW of offshore wind by 2035 to decarbonise the grid.”

What comes next

With the UK’s offshore wind targets now deemed at risk, there remains a number of questions about what comes next.

The fallout of “botched” AR5 will fall to the newly appointed secretary of state Clare Coutinho, notes Mike Childs, Friends of the Earth’s head of policy. She “needs to get a grip on her failing department – and quickly”.

One potential step forwards is for the government to review the parameters of the auctions ahead of AR6, argues consultancy KPMG.

This is echoed by others, such as trade association RenewableUK’s executive director for policy and engagement, Ana Musat, who says in a statement:

“We urgently need government to provide reassurance that next year’s auction round will offer investable parameters and that, in the longer term, a joined-up strategy for maximising the potential of the offshore wind sector is developed.”

Similarly, Rebecca Williams, global head of offshore wind for GWEC, suggests on Twitter that auctions will need to take into account inflationary pressures in auction design – this would bring auctions more closely aligned to others internationally, such as Ireland’s which secured 3GW of offshore wind capacity at competitive prices in May.

Additionally, it needs to take into account increased global competition in the offshore wind sector, stop the “race to the bottom policy” and bring in “proper industry strategies”, she adds.

The need to take into account rising global competition – in particular, in light of the success of the US’s Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s Green Deal – was also highlighted by Energy UK’s chief executive, Emma Pinchbeck.

In a statement, she says:

“The government needs to ensure future auctions recognise the increased costs to develop and build critical infrastructure in the current climate, and produce a robust response to growing global competition for clean energy from the US and EU in the upcoming Autumn budget.”

Other suggested changes from industry include reforms to development consent and seabed leasing, or more radically moving offshore auctions onto a capacity rather than energy basis, as Adam Bell, head of policy at the consultancy Stonehaven, notes.

In an article on LinkedIn, Bell writes:

“I think the change that would most restore trust in the rationality of the system is to remove the scheme from government entirely and hand its development to the Future System Operator. The FSO is already planning where all the pylons will go and will have a much better understanding of the actual capacity requirements of the system, reducing the risk of over-procurement.

“However, the FSO is increasingly the designated vessel for problems that are seen as too hard for the rest of government to solve, so this may be a bridge too far for its function.”

Some in the industry have also suggested that the auction could be rerun. Jess Ralston, energy analyst at the ECIU, for example, says in a statement: “The industry says our offshore wind market, the second largest in the world, is ready to deliver. Will the government rerun this auction with sensible strike prices?”

If there was a rerun of the auction, it would not take a significant adjustment in the ASP to make it more attractive to the offshore wind sector, suggests Thomas Edwards, senior modelling consultant at Cornwall Insight, on Twitter.

Increasing it by “£10/MWh higher it would still have been a good deal IMO, with long-term power prices forecast around £60/MWh”, he writes.

An analyst at one major offshore wind developer tells Carbon Brief that, in addition to raising ASPs, other steps could be taken to make CfD prices competitive, such as extending them from 15 to 20 years and targeting capital allowances.

Extending the CfD by five years has a “surprising impact” due to “merchant tail risk” after the CfD ends, which is pretty big for a ~35 year asset, they note. This is due to price cannibalisation exposure, the levers to address which lie with policy and regulation and are therefore outside of the control of developers.

Additionally, the review of electricity market arrangements (REMA) is “starting to bite”, the analyst notes, with the prospect of the UK moving to a nodal or zonal pricing structure impacting investor appetite.

While REMA currently provides uncertainties, Regen has called for reforms to the CfD to be brought forward to provide a better solution for negative price periods. The current negative price rule, which sees CfD payments cease, introduces too much investment risk and market distortion, it notes.

This is one of a number of suggestions from the market insight company Regen following the AR5 results, chief of which is for the government to make an immediate announcement that it intends to increase support for offshore wind, highlighting the continued ambition of the UK.

Additional suggestions for next steps from Regen include convening a taskforce of industry and supply chain partners to “interrogate what is happening with industry costs”, review and amend the CfD pot structure to separate offshore wind from onshore wind and solar, accelerate grid investment and reset the ASP on the basis of the cost review developed by the taskforce and the cost of capital.

Others suggest that the UK could look at other avenues of support. For example, GEWC’s Williams tells Carbon Brief that the UK could take on board lessons from the IRA, which creates incentives with industrial strategy elements.

“It’s the overall package, not just the price,” Williams says.

According to Offshore Energies UK’s (OEUK) latest Economic Report, £80bn could be spend on offshore wind investments by 2030. But around half of that is waiting on final investment decisions from businesses that “need to be presented with a commercially attractive offering”, according to sustainability and policy director Mike Tholen.

The draft allocation framework for next CfD auction is expected in mid-november, ahead of the AR6 application window opening on 19 April 2024.

Dan McGrail, chief executive officer of RenewableUK, writes on LinkedIn that the government must move “urgently to rebuild investor confidence in this vital industry and demonstrate internationally that the UK is open for business for offshore wind”.

Ahead of the next auction, there are a few simple steps it can take, he suggests. This includes getting the design of the next auction right, with sensible and sustainable prices, publishing the design quickly and ensuring it is big enough to “make up lost ground”.

McGrail finishes:

“These results today put a great opportunity for economic growth on hold. UK energy bills will be £2 billion higher for an extra year, thousands of jobs that would have been created are delayed, £10 billion of investment is delayed, and the 32,000 people who work in our sector will not be able to do what they do best, which is build world class infrastructure based on British ingenuity.

“Let’s make sure this is a turning point.”