Emmanuelle Andrews argues that yes, AI is scary, but these systems can and must be regulated to provide greater public security and purpose

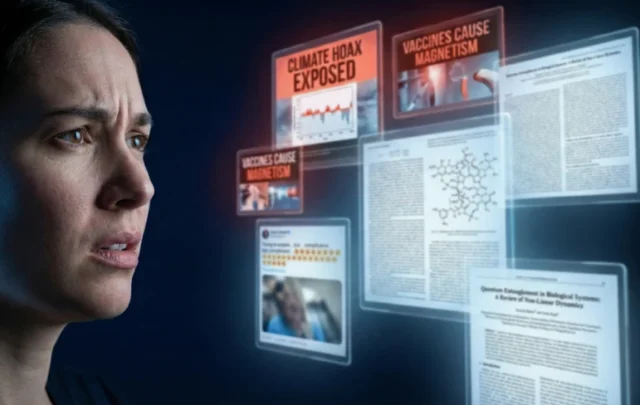

In case you missed it: artificial intelligence (AI) will make teachers redundant, become sentient, and soon, wipe out humanity as we know it. From Elon Musk, to the godfather of AI, Geoffrey Hinton, to Rishi Sunak’s AI advisor, industry leaders and experts everywhere are warning about AI’s mortal threat to our existence as a species.

They are right about one thing: AI can be harmful. Facial recognition systems are already being used to prohibit possible protestors exercising fundamental rights. Automated fraud detectors are falsely cutting off thousands of people from much-needed welfare payments and surveillance tools are being used in the workplace to monitor workers’ productivity.

Many of us might be shielded from the worst harms of AI. Wealth, social privilege or proximity to whiteness and capital mean that many are less likely to fall prey to tools of societal control and surveillance. As Virginia Eubanks puts it ‘many of us in the professional middle class only brush against [the invisible spider web of AI] briefly… We may have to pause a moment to extricate ourselves from its gummy grasp, but its impacts don’t linger.’

By contrast, it is well established that the worst harms of government decisions already fall hardest on those most marginalised. Let’s take the example of drugs policing and the disproportionate impact on communities of colour. Though the evidence shows that Black people use drugs no more, and possibly less, than white people, the police direct efforts to identify drug-related crimes towards communities of colour. As a consequence, the data then shows that communities of colour are more likely to be ‘hotpots’ for drugs. In this way, policing efforts to ‘identify’ the problem creates a problem in the eyes of the system, and the cycle of overpolicing continues. When you automate such processes, as with predictive policing tools based on racist and classist criminal justice data, these biases are further entrenched.

Given these systems inevitably target marginalised groups, it is difficult not to posit that governments deploy algorithms intentionally as social control mechanisms. As Sarah Valentine writes, ‘algorithmic decision-making increases the state’s capacity to dominate vulnerable communities by making it almost impossible to challenge system errors [and] it allows governments to hide these negative effects behind the veneer of technological infallibility.’ In our drugs policing example above, the algorithm runs off data that is race-and-class blind and subsequently correlates poor people of colour with substance use. Anybody who has experienced police abuse or neglect at the hands of the state will be able to attest to how difficult it is to hold state institutions accountable as things currently stand, let alone an opaque algorithmic system built years prior.

But you’ll be hard-pressed to find this kind of analysis in the numerous articles sensationalising the existential threat of AI. Not only are AI and algorithmic decision-making already negatively impacting people but these systems look and move suspiciously like the government, the police and the very private sector tech leaders that claim to be the ones protecting us from harm. The reality is that they’re often the ones perpetrating the violence.

Regulatory loopholes

The UK government’s AI regulation white paper was supposed to respond to the gaps in the current legal framework governing AI. Yet, it has already begun on the wrong footing, placing an inherently capitalist aim of AI ‘innovation’ at the heart of its agenda, a move that will be music to the ears of the very industries that are at the centre of the death-by-AI-robot debate. We call this ‘AI ethics washing’: the industry resisting statutory regulation while simultaneously advocating for their own, industry-created and managed, non-statutory checks and balances as proof that they are taking these issues seriously. For examples of this practice, just take a look at the plethora of ‘ethical codes of conduct’ springing up, steered by the potentially dangerous assumption that industry can voluntarily regulate itself.

As AI governance scholars Karen Yeung, Andrew Howes and Ganna Pogrebna have acutely described it: ‘More conventional regulation, involving legally mandated regulatory standards and enforcement mechanisms, are swiftly met by protest from industry that ‘regulation stifles innovation.’ These protests assume that innovation is an unvarnished and unmitigated good, an unexamined belief that has resulted in technological innovation entrenching itself as the altar upon which cash-strapped contemporary governments worship, naïvely hoping that digital innovation will create jobs [and] stimulate growth.’

And as Liberty and other human rights and tech and data justice organisations have argued, the proposals within the government’s AI regulatory proposals fail to ensure that adequate safeguards and standards are in place for use of AI, particularly by public bodies. Meanwhile, the government is weakening existing standards and stripping back protections elsewhere, from data protection to human rights. Let alone the government’s wider agenda to make the United Kingdom an unsafe place for migrants, those seeking abortion, trans people, or workers, to name just a few.

What can be done?

First and foremost we must demand strong AI regulation, based on human rights and principles of anti-oppression. That includes demanding that transparency be mandatory, that there are clear mechanisms for accountability, that the public are consulted on new tools before they are deployed by the government, that existing regulators have the expertise, funding and capacity to enforce a regulatory regime (or that a specialist regulator is created), and that people can seek redress when things go wrong. Certain AI that threatens fundamental rights, like facial recognition, should also be prohibited outright – something that the government has so far explicitly refused to do but is common elsewhere.

Secondly, organise, organise and organise. Whether you’re a tech worker (who can be demanding strong whistleblower protection policies), or a public sector worker (who can refuse to deploy algorithmic decisions), many of us have a role to play in resisting the oppressive use of AI tools. You can find out where (some) AI is being used by public bodies by looking at the Public Law Project’s Tracking Automated Government (TAG) register. But even if you don’t think you’re being directly harmed, that does not mean you shouldn’t be concerned. We must organise loudly alongside those who can’t be so vocal.

Finally, remember that you don’t need to be an expert (whatever that means) to have a voice in this conversation; often it’s those of us that aren’t that are best placed to contribute to the debate. After all, AI does not arise in a vacuum, but rather is a vehicle to institute wider policy aims. That also means we cannot simply delegate responsibility to the AI engineers. As the co-founders of the AI Institute Meredith Whittaker and Kate Crawford explore in this fantastic podcast episode, ‘a lot of these questions aren’t AI questions! They aren’t about: “are you using a deep neural net to do this,” it’s about: “under what policy is this implemented.” [So] in the healthcare domain you would want doctors, you would want nurses unions, you would want people that understand the arcane workings of the US insurance system […] at the table, on equal footing with AI experts to actually create the practices to verify and ensure that these systems are safe and beneficial.’

Yes, AI is scary, but it is ultimately a reflection of our current system, and it is the introduction of AI into an already repressive environment that we must question. Our movements for justice and liberation must be continually fought for, and hard. Do not let the fearmongering around AI distract you or drive you to despair, may it mobilise you.