As if we needed more reminders of the impacts of Earth’s warming, it’s being reported:

“that climate change is destabilizing the insurance industry, driving up prices and pushing insurers out of high-risk markets.”

State Farm, the largest homeowner insurance company in California, announced it would stop “accepting new applications including all business and personal lines property and casualty insurance.” The company blamed its decision on “historic increases in construction costs outpacing inflation, rapidly growing catastrophe exposure, and a challenging reinsurance market.”

The catastrophe State Farm no longer wants exposure to is wildfires. There’s a strong connection between climate change and the incidence and destruction of these conflagrations. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration links longer and more active fire seasons to rising temperatures and drier conditions.

California is credited with efforts, e.g., the Safer Wildfires Initiative, to increase the fire resilience of their forests. However, for State Farm and other insurance companies, e.g., Allstate, it’s all about the bottom line and solvency. California wildfires in 2017 and 2018 resulted in insurers paying out $29 billion in claims while only collecting $15.6 billion in premiums.

The reinsurance market is itself having difficulties because of the rising risks of Earth’s warming. According to Investopedia,

“reinsurance occurs when multiple insurance companies share risk by purchasing insurance policies from other insurers to limit their own total loss in case of disaster. By spreading risk, an insurance company takes on clients whose coverage would be too great of a burden for the single insurance company to handle alone.”

In California, wildfires are scorching homeowner and business policies. In the low-lying lands of Louisiana and Florida,

“homeowners are facing huge price increases for flood insurance that could cause hundreds of thousands of people to cancel their policies and risk financial ruin if their home is flooded.”

When flood insurance is available, it isn’t cheap. It’s getting more expensive by the day. FEMA estimates the average flood insurance premium will shoot up by 545 percent.

A policy that cost $842 will now go for $5,431 in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. In Collier County, Florida, homeowners can expect a fourfold rise in premium payments. FEMA sells 90 percent of the nation’s flood insurance policies, according to E&E News. Because the agency may only raise rates by 18 percent per year, policyholders will be given a bit of time to adjust and prepare for the rising costs.

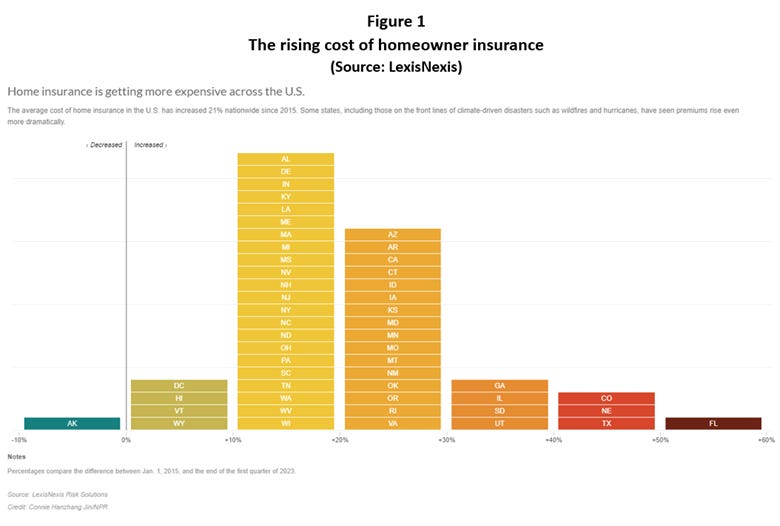

Property owners insured by private companies like State Farm will see the changes imposed all at once. Assuming insurance will still be offered, homeowner insurance is going up in every state with the exception of Arkansas. (See Figure 1)

An insurance company executive neatly summed up where it all seems to be leading.

“We cannot charge an adequate price for the risk.”

Not to put too fine a point on things, but it seems to me there’s a critical lesson to be learned here.

What does it say when the risk-takers see potential damages as too high to cover even with premium increases? It doesn’t take a genius to figure the problem will only get worse as Earth’s rate of warming increases and the price tags of climate-related disasters rise.

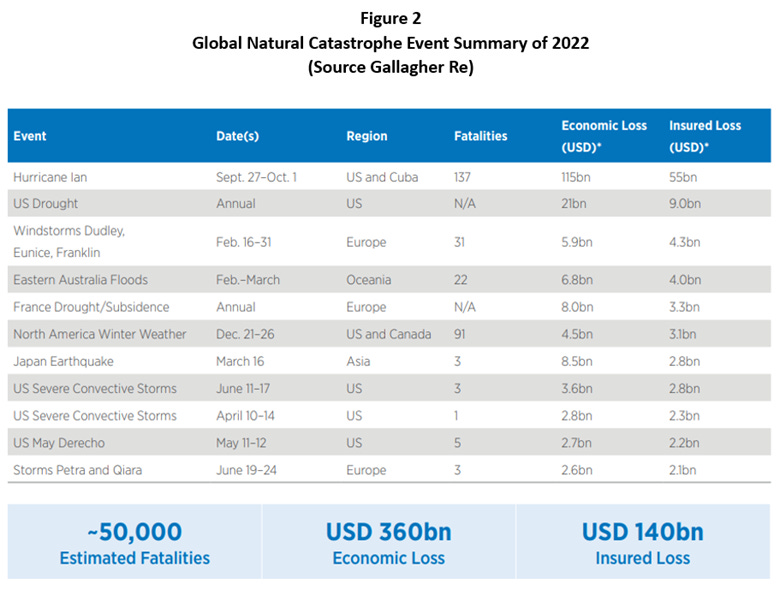

Gallagher Re[insurer] reported that 42 billion dollar weather disasters were experienced worldwide in 2022. The estimated loss from those events was $360 billion, only 39 percent of which was covered by insurance. (See Figure 2)

According to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), there were “eighteen separate billion-dollar weather and climate disaster events” in 2022. They included:

- Eleven severe storm events (tornado outbreaks, high wind, hailstorms, and a derecho);

- Three tropical cyclones (Ian, Fiona, Nicole);

- The Kentucky/Missouri flooding;

- A late-December Central and Eastern winter storm/cold wave; and

- The Western and Central drought/heat wave and Western wildfires.

The cumulative cost of these events exceeded $165.0 billion. The events of 2022 are no exception to the trend. 2023 has already seen some of the highest temperatures ever recorded. Ocean waters off the coast of Florida are said to about that of a hot tub—101 degrees Fahrenheit. These warm waters will soon be powering hurricanes.

In five of the last six years (2017-2022), the annual cost of big-ticket disasters exceeded $100 billion. Between 2016-2022, total damages were more than $1 trillion. By comparison, the total costs for 360 events from 1980-2023 amounted to $2.570 trillion (inflation-adjusted to 2023 dollars).

The rising cost of insurance could hardly come at a worse time. High interest rates, and inflation impacting everything from hourly wages to the price of potatoes, along with escalating premiums, are conspiring against potential homebuyers. Without insurance, home buyers are unable to secure mortgages.

The insurance dilemma is not limited to the US. The International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) believes it likely that

“all insurance businesses will be directly or indirectly affected over the long-term—regardless of their size, business line, domicile or geographic reach.”

It’s crucial to understand that the solvency of insurance companies impacts more than just the company and its policyholders. Insurance groups are “both large institutional investors and underwriters of risks to financial firms; many insurance companies are major players in the financial services industry and are important to maintaining financial stability.”

The near-failure of the American International Group (AIG) was a significant contributing factor to the 2008 financial crisis. Bad real estate bets resulting in the loss of $99.2 billion roiled financial markets and helped lead the way to the Great Recession.

Insurance companies make money in two ways—premium payments and returns on investments that also help to diversify a company’s risk. According to McKinsey and Company, evidence is mounting that property and casualty insurers need to reshape their business models because of the enduring and increasing threat of climate change.

McKinsey identifies several crucial traits of physical climate risk that need to be believed and understood for what they’re telling us to expect.

- Because physical climate risk is increasing, so is the scope of risk aggregation and the prospective economic impact. Some risks may become difficult to insure at reasonable rates.

- Effects will be systemic…the initial impact of a discrete event will set off a chain of knock-on effects. A natural catastrophe, for instance, may destroy property, cause business interruption, damage ecosystems, and create a humanitarian crisis. Because of the interconnected nature of systems, there will be greater volatility.

- Effects will be regressive: the poorest communities are typically the most vulnerable. Emerging economies face the largest increase in the potential impact on workability and livability. Less-developed economies rely more on outdoor work and natural capital and have fewer financial means to adapt quickly. The protection gap in developing economies will probably increase without collaborative intervention from insurers and governments.

- Human systems are underprepared to manage the rising physical climate risk and its effects. The pace and scale of adaptation will need to increase significantly. Insurers could, for example, offer risk engineering and risk-mitigation services.

There isn’t anything in the above list that isn’t going on now at some level and that promises only to get worse without a rapid and rational response.

The future—our children’s future—is on the line here. It’s preposterous to call clean energy alternatives atrocities, sources of cancer, and all manner of poison and pollution. What’s worse is equating science-based efforts to combat Earth’s warming with the rise of some socialist, Marxist, ideologies. If a sustainable and just world is revolutionary, then where do I sign up?

If things don’t change then sooner or later, the federal government will be called upon to be the insurer of last resort. The National Flood Insurance Program is an example of what happens when insurance companies have less money coming in than going out. California’s FAIR plan is another state-backed pool of insurers who provide basic coverage for a high price as a last resort.

Public and private insurance companies will keep raising premiums to the point where they cannot charge an adequate price for the risk. Even governments will get to that point; it may just take longer.

The impact of an unhealthy insurance market reverberates through the economy. The First Street Foundation estimates there are 14.6 million properties in 100-year flood plains. According to NOAA,

“roughly 21 percent of the country can now expect their ‘1-in-100-year flood’ to happen every 25 years. And in the most extreme cases, over 20 counties in the US – home to over 1.3 million people – are expected to experience the current ‘1-in-100 year flood’ severe event at least once every 8-10 years.”

What would happen to the owners and the economy if many of the nearly 15 million at-risk properties were flooded out without insurance? What would happen to mortgage markets with so many homes and businesses going underwater—literally and financially—every eight to ten years?

McKinsey estimates that “the value at stake from climate-induced hazards could, conservatively, increase from about 2 percent of global GDP to more than 4 percent…in 2050.” Ensuring a sustainable future is not just about insurance premiums. It’s also about good planning and fair regulation.

It’s one thing to compensate a homeowner whose abode burned down or flooded out. It’s another to allow re-building on a flood plain—once, twice, three times. What do they say it’s a sign of when you keep doing the same thing repeatedly, expecting a different outcome?

Who doesn’t want to ensure a better life for themselves, their children, and their grandchildren? Whether one chooses to recognize the overwhelming scientific evidence of the causes and consequences of Earth’s warming or not, it’s happening. When the risk takers begin to bale out of a market or announce ever increasing premiums, you can be sure there’s more trouble on the way.

It’s time America to stop the political posturing on climate change and do—together—what’s necessary to ensure current and future generations of a sustainable environment and economy.

The way to ensure a sustainable future does not start with lying about the events of today.