This past week I was reading an older book on the trauma of living within our culture and had another run-in with the theory that everything went to hell when humanity decided to farm. This book is old enough that the arguments against agriculture were still novel when it was written, so I forgave the author for falling into that ahistorical quagmire. However, there is one point that struck me this time.

Farming is not the problem with our culture. We’ve always controlled our food sources. That’s what animals do. Those who can create a sufficient supply of food to meet their bodily needs get to live and reproduce. Those who don’t regulate the food supply usually die and eventually dwindle to extinction. Furthermore, there is also not much evidence in the human story to support this theory that farming spread devastation. Farming existed and continues to exist without creating devastation. The changes that took place around 8000BCE in some places, the changes that led to intensified devastation for humans and the rest of the world, were mostly in ideas. Ideas about superiority and status. The idea that humans were above the rest of this world and to a large extent not of this world. The idea that some humans were above all the rest. The idea that there is rank in the world, and those with higher rank were given more resources — even the labor of other humans.

These ideas on hierarchy created a culture that excused devastation. The old world order saw humans, all humans, as embedded and interdependent organisms within a larger organism. The old world order did not allow for hierarchy because all things were equally important to the proper functioning of the world. Certainly, humans, being not very central to making life, were not seen as superior and therefore allowed to take whatever they fancied of the world for themselves, without thought for consequences. Because, obviously, the consequences of taking and not giving back, of damaging other parts of the whole, of merely seeing the whole as a collection of inert objects, that all hurts everybody — even those who fancy themselves superior — and the consequences range from waste and destruction to the trauma of living in a world without meaning, a dead world, a world of things that must be escaped.

These ideas were novel around 10,000 years ago and probably arose because there were new climate stresses in the world that disturbed ecological balance and caused local scarcity. And for as long as humans were small relative to the resource pools of the world, these ideas were a path to success for some. Some (mostly) men benefitted wildly from their divorce from the material world. They were able to arrogate wealth — initially defined as food — and they were able to use this wealth to buy coercion. This, then, became a feedback loop. More wealth, more ability to buy the means to take more wealth. These ideas were most successful where resources were restricted — because it is very hard to coerce people who can feed and shelter themselves. But once a few regions saw the rise of hierarchy, imitations spread. Because it’s also hard to argue with success.

I tend to think that the social contract was not a leadership that provided protection of low status people from marauding outsiders. It was the compact between the aspiring leaders and those that would support that project. Warlords and warriors. Kings and knights. Elites and their mercenaries. They were the marauders wherever they arose. And it began with that rise, the creation of superiority for those who would commit violence against the world and the inferiority of everyone else.

This has nothing to do with how food is sourced and produced. Nor even stored. It has everything to do with how food is distributed. The crucial bit of evidence is that farmers have never been among the elites. Those who created the means to meet bodily needs were placed at the bottom of the hierarchy and remain there still. The central task of the coercive force was, and remains, to ensure that those who produced the basic necessities were the least likely to benefit from that production.

In some of the places this new idea found fertile ground, there was a concomitant rise of urbanization and centralization. But this was largely an ancillary effect of concentrating wealth and high status into a small number of people, especially in places with scarcity. It’s also just easier to control your coercive force — be they dogs, soldiers, priests or accountants — if you keep them close and fed at your hand. But again, it is not civilization or concentration of human populations that causes devastation. There are many ancient cities that show little evidence of hierarchy and, significantly, these egalitarian urban centers existed for centuries, sometimes millennia, longer than those with kings and warlords reigning over an enslaved population of producers. These were places that thrived in balance with their world. Some farmed, some traded with farmers, many practiced the blend of herding and foraging and gardening that is most common to human food-ways. So the fault lies not with cities either, per se. Waste and devastation come from hierarchy, the rationale and motive for both.

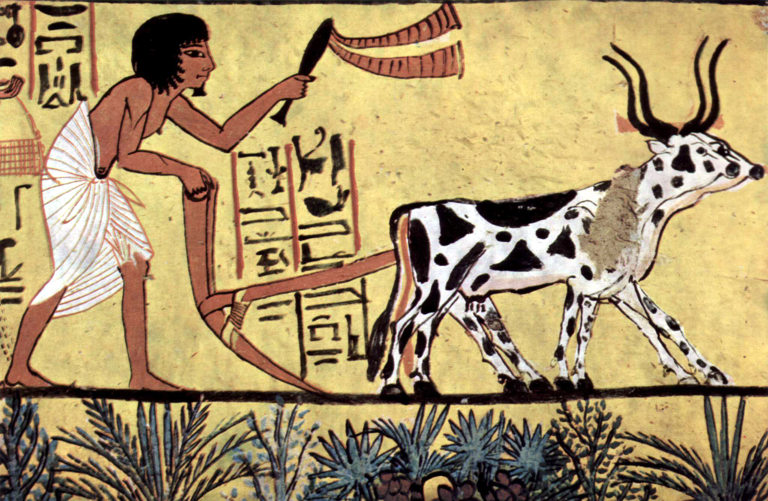

But back to the book I was reading. The author made me aware that there is one thing about farming that does change when kings begin to reign, and it is something that does cause widespread ecological devastation. It is the plow.

Look at this tool. To begin with, it must be forged from mined and smelted ore. To merely create this tool is already an act of great destruction. To use it is worse. And it is counter to all wisdom of growing plants. Our ancestors knew that undisturbed soil nurtures the healthiest plant communities. They knew that breaking up soil led to erosion and loss of fertility. They might not have known about the microbial webs of organisms that process, store and transport nutrients, but they did know that earth was living — and could therefore die if damaged. So why invent a tool that damages?

I believe that this too was an ancillary effect of hierarchy. Those new elites were not farmers. Men have never made up the majority of food producers, so it is statistically likely that those who first seized power never had much knowledge of soil. But after a few generations of being apart from production and of actively denigrating anything to do with productive work, it’s also likely that they forgot what little they ever knew. So they just didn’t know how stupid the plow is.

On the other hand, their project required an increase in food surplus relative to the number of farmers. Each farm had to produce enough to keep the farmers alive as well as surplus to send off to the new class of elites and mercenaries who did no productive work. They didn’t understand farming or growing food but they were dependent upon it, and they were dependent upon it producing increasing quantities. This accounting led to increased pressure on farmers to produce more and more in the short term, even though they knew the lands would fail in time. Hence the plow.

It is bad to disturb soil for nearly every kind of living organism except one: the plants that colonize natural disturbance. These short-lived species take advantage of the lack of competition for sunlight, water, and what accessible nutrients there are in the dirt. They live fast and furiously, many for no longer than one growing season, creating dozens, hundreds, of seeds. In natural places, these annuals decompose and, with their bodies, begin to rebuild the communities of organisms that make up the living soil. And with every growing cycle they become less successful, less dominant, until perennial plants and trees become established and the annuals are pushed to the margins.

But those seeds are built to last. Long after their parents are gone. Annual seeds are designed to endure until the next disturbance creates the exposed conditions they need. Annual seeds are produced in profusion in a short span of time and then can be stored for a very long time. Animals figured out this rhythm of bounty long ago. Many animals actively promote the conditions that allow annuals to grow. Humans are one such even though we can eat little of annual plants but the seed — or seed case, the fruit. And like ants, we figured out how to harness heat and microbes to process the plant materials into digestible form. Our favorites were the grasses. The grains. Because each year these tidy plants produced huge harvests of easily transported and stored nutritious seeds in a relatively compact space. And all the farmer had to do was destroy the existing plants.

For elites seeking ways to feed their supporting staff, the plow was the ideal tool. Farmers were probably less enthused, but I suspect they had little choice.

It is significant that the plow was not created when farming began, nor was it quickly adopted in all farming communities. There are many regions where the plow is known and yet unused. This is explained away by those who don’t farm as a function of poverty or ignorance or difficulty of terrain. But the simpler explanation is that most farmers know that plowing only produces one harvest. One type of food. When we need many types of food to be healthy. And only one year of harvest. When those who farm, those who work with the land, know that it takes many hungry years to remediate damaged soil.

The plow is the tool of those who want to wrest short-term gain from the land. The plow is used to grow wealth, not food. The plow does not mark the rise of farming, but the rise of elites. The plow shows up in the archeological record in the same places and time periods as the rise of this new elite class and their henchmen, and it follows that mode of cultural organization all around the globe. It is another tool of coercion. It is not evidence of farming; it is evidence of hierarchy.

The author of the book that prompted all these thoughts on the plow called it a tool of the elite, that the plow created the elite class. Those who gained access to this tool controlled the flow of wealth, and so they became elites. The book seems to say that before the plow, there were no elites because there was no method of creating the amount of surplus necessary to feed an entire class of people who did not farm. I am not one who believes in the effectuality and agenda of technology, and in any case the plow, like all technologies, did not invent itself. It was created by people who benefitted from it. And, given what I know of growing food, I doubt those people were farmers.

I think the plow is hard evidence that the problem is not that humans were managing their surroundings to produce food and shelter. Nor even that humans were becoming more inclined to live in somewhat permanent settlements near their farms. Farming and villages both came before the plow. Humans had domesticated many species, animal and plant, millennia before the invention of the plow. Humans continue to encourage food growth the world over, and yet there is little correlation between ecological destruction and the kinds of farming that don’t involve the plow. But in the record it is almost impossible to separate the rise of elites and the adoption of the plow. And, while the plow has been used in sustainable ways here and there, elites are universally associated with destruction and eventual collapse.

And I would submit that it is the idea behind the plow — the idea that humans are so specially superior that they are allowed to cause widespread death and destruction in the name of satisfying their wants — that is the actual root of all our culture’s problems. This is the idea that created the plow. And this is the idea that created hierarchy. And this is the idea that enables both to continue to spread harm in our present world, harm that will, like the death of the living soil, take many lifetimes to rehabilitate.

Teaser photo credit: Ancient Egyptian ard, c. 1200 BC. (Burial chamber of Sennedjem). By Painter of the burial chamber of Sennedjem – The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=154346