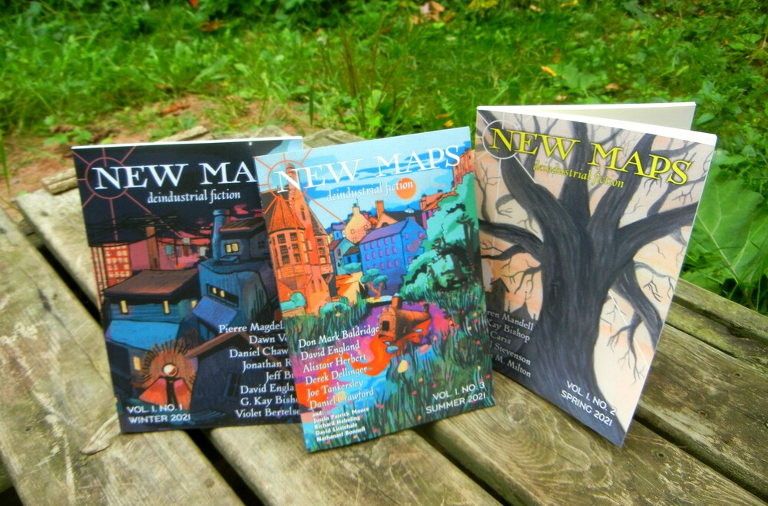

Ed. note: This piece was first published in the first (Winter 2021) edition of the New Maps journal.

Ed. note: This piece was first published in the first (Winter 2021) edition of the New Maps journal.

The first time I encountered Always Coming Home—sitting on the table of someone I was visiting in northern California, not far from where its stories take place—I opened semirandomly and found a transcription of characters from the village of Chumo having a poetry battle with characters from further down the Valley.

Down the Valley the intelligence of the inhabitants

is manifested in their custom of brewing

small beer from dog turds.

People keep a lot of chickens up in Chumo.

The chickens are so clever, they talk like people:

Rock, rock, rock, rock, rock, rock, rockbasket!

The people in Chumo are as clever as the chickens.

On the next page is a “poem said with the drum” attributed to a character from a different Valley town:

The hawk turns crying, gyring.

There is a tick stuck in my scalp.

If I soar with the hawk,

I have to suck with the tick.

O hills of my Valley, you are too complicated!

I didn’t quite know what I was looking at, but I knew at least that it wasn’t like other books I had read. With a little more paging through, I was satisfied that whatever it was, I would someday need to read the whole thing.

Having finally gotten a copy of my own several years later, I can confirm that it isn’t like other books. Always Coming Home is not a single story but a collection of texts that weave together to elucidate the complex and quite unfamiliar culture of the Kesh, a people who “might be going to have lived a long, long time from now in Northern California.” The culture that you or I would find if we visited the environs of the Napa Valley today is remembered only in stray fragments of folklore, as “the Red Brick People” after the only modern product still remaining after five or ten thousand years, or “the City of Man,” which one character visits in a perilous vision to find all the people have their heads on backwards on their shoulders. The shortest of these texts are poems a couple lines long, and the longest the 99 pages of the harrowing life story of an old woman named Stone Telling. They include short plays, songs, a chapter of a novel, personal accounts, pen-and-ink sketches, proverbs, and types of art that we have no word for, like the tabetupah or “hearthplay.” In the beginning Le Guin asks the reader’s forbearance to “bear with some unfamiliar terms [until it] will all be made clear at last,” and as you take in more and more, it does come clear in a most satisfying way. You end up with a quite vivid understanding of what the Kesh are like, what they consider wise and unwise, how they understand the world, so that eventually you look at things happening in your own world and think, for example, “Oh, the Kesh would never allow that to happen.”

If it sounds like there’s a pronounced anthropological bent to all this, that’s no accident. Le Guin was the daughter of the famous Kroebers (that’s what the K. stands for), superstars among ethnographers, to the extent that such phenomena exist. Her mother Theodora wrote the famous Ishi in Two Worlds; her father Alfred founded the anthropology department at UC–Berkeley, and was allegedly such an influence to the nascent discipline that a whole generation of young men in that field across the country grew beards just like his. It’s interesting to imagine what their dinner table was like; it’s known that some of the time it was shared with a Tohono O’odham man, Juan Dolores, who stayed with the family for weeks at a time, teaching the Kroebers about his culture and spending time with them, and in time became like an uncle to young Ursula.

Professorial as this may make the book sound, I believe Le Guin’s background should be cause not for suspicion that a dry lecture awaits (it doesn’t), but for relief. Having genuinely tried to understand, as much as an outsider may, some cultures vastly different from her own, Le Guin for the most part avoids the common mistake of assuming all cultures are more or less like the mainstream globalized industrial one. So instead of aliens suspiciously like twentieth-century Americans down to the ranks in their military hierarchy (paging General Grievous), here you find Californians so unlike the people alive today that we must concede they live in a different world.

Nor is this, as one reviewer fondly called it, a simple novelization of her parents’ studies of the Yurok and Yahi. On a superficial level, it’s hard not to note that the Kesh have a little electricity, a powered cotton loom, and even access to something vaguely like the internet, among other modest nifties preserved from the past. But seen more deeply, although her parents’ ethnography is clearly present, the Kesh give the impression not of being just like the “first-comers,” nor of being pristine Rousseauian nature-people, but of living with wisdom inherited from survivors of a bad period of history, even though that history happened so long ago they know nothing of its stories.

Is it naively utopian? On one hand, of course it is. The Kesh are peaceful, well fed, wine-brewing, sexually liberated, matriarchal wish-fulfillers. Le Guin herself was aware of this problem; a little past the halfway point of the book, she orchestrates a dialogue between herself-as-narrator and a Kesh village archivist, in which she accuses the archivist’s world of being a utopia, and the archivist rejoins that it’s no such thing—it’s “a mere dream dreamed in a bad time … by a middle-aged housewife, … a critique of civilization possible only to the civilized, an affirmation pretending to be a rejection, a piece of pacifist jeanjacquerie.”

On the other hand, Le Guin’s own objections notwithstanding, if it’s utopian, we can’t accuse it of being naively so. The Valley is not a simple paradise. It has people who are unhappy, for instance, some of them severely so. One charge leveled against the idea that a pacifist culture can exist is that without violent defense capabilities, the people will be easily conquered. The book’s longest story serves at least partially as a rebuttal to that charge. It’s acknowledged that the Kesh’s matriarchy gives men short shrift, risks seeing them as better suited to stay in the gardens and the workshops than to try to grasp the lore of the temples. Not all is well in the Valley, and for that reason we can take these people seriously—their hardships aren’t ours, but they’re as real as those of fictional people can be, and they don’t have easy answers for everything. I respect that. Le Guin stress-tests her utopia for us, and though as its loving creator she may have pulled some punches, still it holds believably firm.

Always Coming Home must stand as a landmark of deindustrial literature, from years before the genre was ever named. Its scope of imagination is vast, encompassing dozens of characters communicating in dozens of kinds of texts; its detail and richness are totally immersive; the possibilities it explores were in large part uncharted before it and many otherwise remain so 35 years later. It is also one of Le Guin’s most sympathetic and vulnerable works; readers expecting the austerity of style that marks her other work like The Dispossessed and the Earthsea Cycle will find that style colored in with winks, personality, and humor. It is a work of enough complexity that its title page lists not only Le Guin as author but also a composer (an accompanying CD is available), an artist, and a geomancer, though with Le Guin standing at the head as conductor of this symphony.

Always Coming Home was first published in 1985 and has, as far as I can tell, not been reprinted since 2001. Even at the rock-bottom prices of your friendly neighborhood internet megacorporation, a used copy is usually hard to come by for less than $15 US. It’s hard to explain the unwarranted obscurity of a work of such breadth by such a famous author. It may be that its unusual structure puts off readers who expected to dive right in at page 1 and read a single narrative straight through to page 525. Or it may be that literature that prophesies a real and final death to our own time and (heresy!) the existence of hope and happiness after it has always had a harder time finding a toehold than space operas and evil AIs. Whatever the case, this is a rewarding book that deserves a place in the deindustrial canon. It will transport you, and may even change your ideas of what a book can do and be.