The cost of living crisis continues to inflict misery on working people from Columbus, Ohio to Colombo, Sri Lanka. As eco-socialist prononents of degrowth, we aspire to a world in which living does not have a cost, but we have yet to convince the public of the feasibility of this dream. Unfortunately, our responses to inflation and its corollaries have been few and far between. In contrast, neoliberal cranks have taken the opportunity to provide an onslaught of fantasy solutions to reduce inflation. Their proposals are distinguished by their distinct lack of any basis in the available evidence. Moreover, rising prices are a problem that the public cares about deeply, and by disengaging from the issue, the degrowth scholarship risks missing the opportunity to communicate the urgent need for social-ecological transformation to the working classes we need to convince. This piece is a brief attempt to improve the situation by identifying root causes of inflation, and putting forward solutions that can contribute to stabilising ecosystems as well as family budgets.

On July 1st, the European Central Bank (ECB), following many others, decided to raise interest rates for the first time in over a decade. Its president, Christine Lagarde, has described her policy as “nimble“, but interest-rate hikes are a blunt instrument. The logic behind them stems from the belief that inflation is driven by the money supply. Higher interest rates will mean fewer loans—less money creation—and, in theory, lower inflation. As we will discuss, not only does this diagnosis fail to pinpoint the primary drivers of inflation across the continent, but the response could well be pushing the global economy into a recession before inflationary pressures are curbed. Some economists, such as Cédric Durand, argue that the financial system is so highly leveraged that raising interest rates will prove disastrous. Nonetheless, why should we not trust an institution like the ECB with such a proven track-record in predicting inflation?

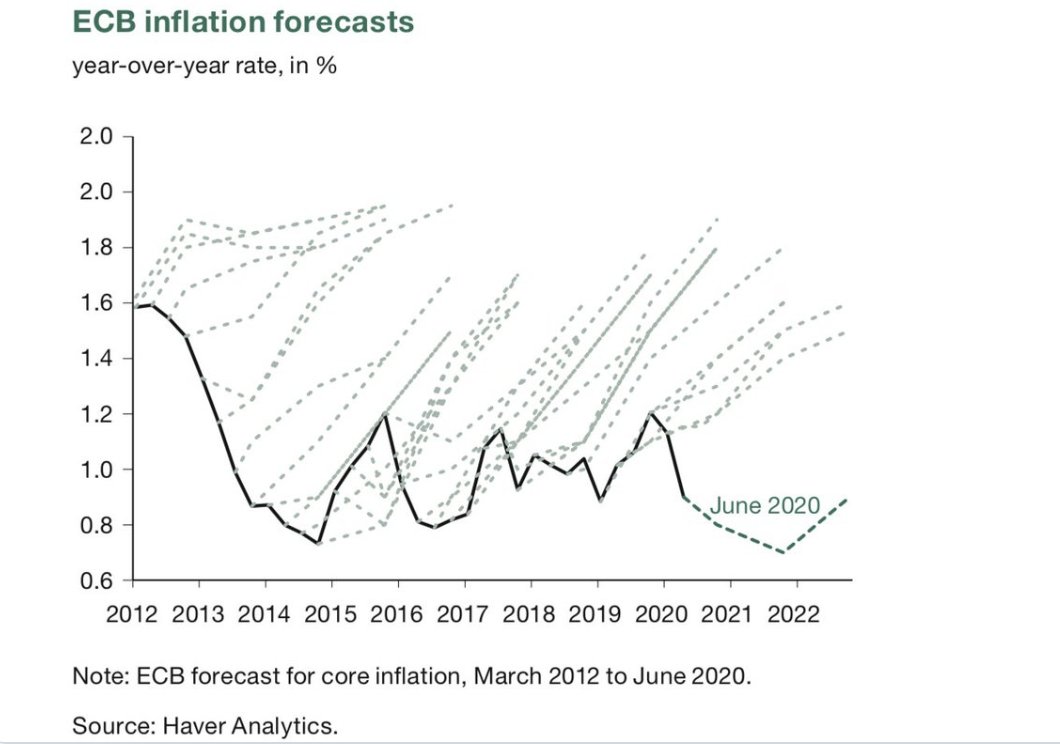

The ECB’s comically bad projections for inflation over the past decade.

Groggy governments, cowed by forty years of monetarism, have delegated all responsibility for lowering inflation to their central banks. Conventional monetary policy provides a limited toolkit for this task, however. The interest-rate hikes we see today are therefore not a surprise: if all you have is a sledgehammer, everything looks like a nail. The problem is that today’s inflationary pressures do not result from the money supply, but from a number of factors that vary according to region and include supply bottlenecks, depressed productive capacity, increased demand for specific goods and services due to the pandemic, and corporate profiteering. One of the primary drivers is the price of oil and gas, in part because of the uncertainly caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the volatility of the futures markets on which these goods are traded. Given that fossil fuels remain our primary source of energy, their price impacts everything from electricity to food. Another key driver of inflation is corporate profiteering—let’s not forget who actually sets prices!—rather than labour costs (as was the case in the wage-price spirals of the 1970s). Corporations have used this crisis to increase their profits and wages have not kept pace with inflation. Blaming the cost of living crisis either on pandemic stimulus packages or workers is simplistic and dangerous.

Given these underlying drivers of inflation, interest-rate hikes are not going to cut it. In fact, raising interest rates can even make inflation worse as it acts as a subsidy to bond-holders and discourages investors from increasing productive capacity. Instead, price caps, targeted investment in relevant sectors, nationalisation and decommodification of essential goods and services can all reduce inflation more effectively than raising interest rates. If our governments were to invest in an energy transition to renewable energies produced domestically, inflationary ripple effects would ease and energy prices would stabilise across the board. Interest rate hikes are at best a blunt and ineffective tool, and at worst a mechanism for inflicting unemployment, hunger and pain on low-income communities.

So instead of buying into monetarist anti-worker propaganda, what could we do to ease the pain of inflation without sacrificing the living world? Enter a Green New Deal (GND) without growth. The GND was first developed in reference to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal as a plan for insuring that a rapid transition to sustainability insures justice for those affected by it, and protects vulnerable communities in a destabilising environment. Proposals have emerged in the the US, the UK and Europe with growing calls to recognise the international dimensions of the polycrisis through a global GND. In its more radical, anti-imperialist formulations, the GND remains as relevant as ever.

Indeed, the current inflationary crisis has not made the need for social-ecological transformation any less urgent. Rising well-being across the Global North has stalled following forty years of neoliberalism, the Great Recession and subsequent austerity measures. The Global South continues to have resources, energy and labour drained from it through neocolonial arrangements facilitated by institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—witness what is happening in Sri Lanka. In addition, every passing day brings us closer to ecological collapse. In this context, a degrowth GND could harness public anger over inflation in order to end the cost of living crisis while setting humanity on a course for all to live well within planetary limits.

In the Global North, a GND without growth would aim to reorient productive capacity away from growth at all costs towards ensuring that the basic needs of all are met without overshooting environmental tipping points. In the medium term, this reorganisation would reduce the cost of living by decommodifying key goods and services including healthcare, education, transport, energy and water. A public Job Guarantee—complemented by a universal basic income for those of any age who cannot work—on a reduced working week paid at a living wage would create a benchmark with which the private sector must compete. It could also boost productive capacity in local food, renewable energy, care and nature conservation, while deprioritizing sectors that do not contribute to meeting essential needs.

Thanks to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) scholars, we know that in order to fund this drastic change in priorities, governments need high economic agency. In other words, they must 1) collect taxes in its own currency, 2) maintain a floating exchange rate and 3) limit government debt in foreign currencies. Under these conditions, governments can spend money into existence without first raising taxes or issuing bonds. Crucially, the limiting factor is inflation caused by excessive demand for goods and services proportionate to a country’s productive capacity—recall what is currently happening with oil and gas. If a government commissions the creation of a new train network at a time when there is a shortage of steel for the rails, that creates inflationary pressure. Domestic productive capacity is what should be considered when designing a federal budget. Taxation constitutes a means of decreasing aggregate demand and reducing the social inequality driving ecological collapse. A better understanding of governments’ role in the creation of money puts an end to the perennial albatross of arguments about how we are going to pay for it and risks of capital flight.

On an international level, climate and colonial reparations must include debt cancellation and structural changes to the IMF and World Bank in order to allow the Global South to increase its own productive capacity and economic agency. These reparations must free Global South countries from the yolk of neocolonialism, enabling them to increase their energy and food sovereignty and to lift their populations out of poverty while adapting to a changing climate.

While there are considerable political challenges involved in realizing the goals outlined here, we can improve the political feasibility of them by challenging the neoliberal narrative about the causes of the current crisis and its possible solutions. In essence, what we need is a compelling alternative story to neoliberal austerity that can harness the common frustration of low-income communities, workers, and environmentalists across the South-North divide, in order to build the power necessary to advance an eco-socialist politics of radical abundance for all. Proponents of degrowth must capitalise on the current crisis and press our advantage. Informed by MMT, degrowth can offer not only a coherent response to the cost of living crisis, but a roadmap for a global GND that ensures that each of us can fulfil our birthright to flourish within the limits of our planetary home.

Teaser photo credit. Sledgehammers. By Shakespeare at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5988973