Democracy Rising is a series of blog posts on deliberative democracy: what it is, why it’s powerful, why the time is right for it, how it works, and how to get it going in your community. The series originates in the United States but will discuss principles and draw upon examples from around the world. Views and opinions expressed in each post are those of the individual contributor(s) only.

Democracy Rising 25: Young Children as Classroom Citizens

Children begin to learn about their roles as citizens in a democracy when they are very young. They often acquire this knowledge informally and indirectly. However, when educators intentionally include this in the curriculum, it can be a transformative experience for both teachers and students. Recently, ten elementary school teachers participated in a two-year Kettering Foundation research project that explored how to integrate deliberative democratic practices into their teaching. All of the teachers were surprised by how readily their young students learned and demonstrated democratic capacities, including agency, empathy, and a sense of what it means to be part of a community. The students also improved their communication and decision-making skills and became more interested in academic subjects.

As is the case with adults, most students in the United States live in hyper-networked, technology-mediated societies. Deliberative practices ask them to slow down, think, and focus on relationships. Listening, turn-taking, perspective-taking, consequential thinking, and the ability to express disagreement respectfully can lead to a deeper sense of belonging in their classroom communities. While rewards and punishment may be an efficient way to shape students’ behavior, these strategies reinforce a view of citizenship in which students are acted on by an authority, rather than acting as citizens or problem-solvers.

Kettering’s research with educators found that deliberative ideas and practices should be introduced in stages that correspond with the cognitive, social, and emotional features of each grade level and each individual. Even kindergarteners can learn and use deliberative skills in real-life contexts with the support of adults. As students move up in grade-level, these basic skills and concepts provide the foundation for deliberating about more complex issues. Students may begin with taking a deliberative approach to address school-related conflicts or issues that happen in their everyday lives during recess and in the lunchroom. This approach also has usefulness in the context of establishing classroom rules and procedures and in addressing friendship challenges. As they move to upper grade levels, deliberation can be used to explore broader social and historical issues that are part of their academic curriculum.

“Several years ago,” one kindergarten teacher wrote, “I . . . thought that the children in my classroom were too young or not yet developed enough emotionally and socially to engage in empathy, agency, and decision-making.”

While kindergarteners are primarily focused on their own emotions and only beginning to understand the feelings of others, deliberative practices can support the development of this significant social skill.

This teacher began teaching deliberative decision-making by using everyday social challenges that her students experience as opportunities to engage them in thinking about their choices and the way each choice affects others. For example, it’s not unusual for a young child to grab a toy from another child. Naturally, there is the impulse to grab it right back, which results in hurt feelings, shouting, or a struggle. Role playing with a student volunteer who understands what is about to happen, the teacher grabbed a toy from the volunteer. Pouting and yelling ensued on both sides. Watching this scenario helped students to empathize with the child whose toy had been taken. When they were then asked by the teacher to suggest some different ways of responding, suggestions included “Can I please have my toy back?” “We need to share,” “It is not kind to grab,” and “Maybe I should go and play with someone who is being nicer.” The goal is for students to understand the effect of their actions on others (which is easier for them when an adult—the teacher—behaves in such an unusual way). They also are more aware of some additional ways to respond if they are the target of the toy-grabber.

It’s also challenging for kindergarteners to transfer knowledge from one circumstance to another. For example, a student may yell to a teacher that another child is talking too loudly, which violates what they have learned about respectful classroom conduct. The child who is reporting the offense is unaware that he or she is doing the same thing as the offender! Working with children to increase their awareness of the choices available to them can help students learn how to apply what they are learning in a generalized way to real life situations.

Another teacher observed that for most first graders, “The classroom is their first social world.” In the world of the deliberative democratic classroom, children are treated as citizens. The physical set up, classroom jobs, responsibilities, and schedule serve as a microcosm. In one first-grade classroom, instead of individual sets of materials, students share buckets of crayons, markers, glue, and scissors. On the first day of school, the students learn how to take care of the materials and the space. Everyone is expected to help clean up a mess, even if they aren’t personally involved in making it. Through sharing materials and being responsible for their space, students began developing collaborative skills and an internal sense of responsibility, a big step for young children.

This first-grade class held deliberations to select a class science fair topic. Students came up with more than 20 possible topics. As they considered their options, hard-to-study subjects such as dolphins and cheetahs were eliminated first. Then students considered the trade-offs and benefits of the remaining animals and eventually decided to study scorpions, something the teacher would never have thought of, much less recommended. Since she was committed to teaching the students that they had the agency to select their topic, she went with it. Because they had made their own decision about what to study, the students were very committed to learning as much as they could about scorpions. The project won first place at their school and third place at the regional science fair.

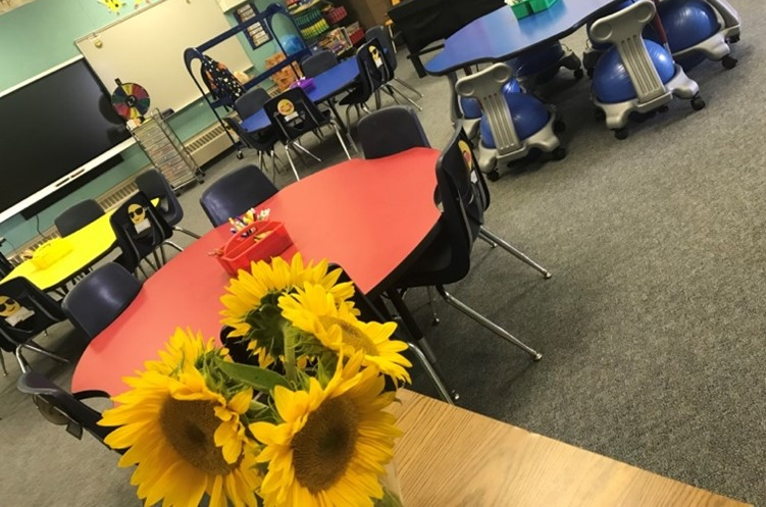

Students learn not only from their teacher, but also from one another. One second-grade class had two rounds of deliberations about whether to sit at partner desks (which they called neighborhoods) or at round tables (dorms). In the neighborhood setup, students were responsible for keeping their own desk clean and each had their own supplies. In the dorm setup, students shared a space and supplies with others. In the first deliberation, students considered which setup they thought they would like best and its benefits and tradeoffs. Then the class was divided into two groups, with each group experiencing a week in each setting. During the second deliberation they once again considered their preferences, benefits, and tradeoffs—this time within the context of their experiences. Most students decided they preferred the dorm community better. Just as dinner conversations wouldn’t be the same if people sat at separate desks instead of sharing the same table, students enjoyed the dorm setup because it provided a more enjoyable social environment for learning, listening, communicating, and participating.

In the third grade, children often take their first standardized tests and experience more complicated social dynamics. Academic challenges are increasing. At the same time, their social world is changing. Instead of being friends with everyone, they are becoming friends with a select few. They have to learn to work by themselves and remain part of a community. They need to mind their own business and still care about their fellow classmates.

A group of third graders were given responsibilities for classroom management and academic learning. Classroom jobs, which rotated monthly, included pencil sharpener, messenger, teacher assistant, phone, supplies management, cleanup, line leader, door holder, and lights. The students learned that their role was important because if they didn’t do their job, it affected the class. While initially reluctant, they learned to ask for help whenever it was needed because it made the classroom run more smoothly. They also learned to identify themselves as a community of learners who cared about one another. While the teacher guided and directed the learning, students also had a say in how and when it happened. For example, a few days a week, students would decide when they had recess and when they would do their academic work. For each of these decisions, students would discuss the benefits and drawbacks of various options. At the end of the day, they would reflect on how it went for future reference.

By the close of the project, it was clear that students weren’t the only ones who had learned from the deliberative classroom communities. One teacher reflected that before the project,

“I really did not think that my classroom had any foundation in democratic principles. When I thought of democratic principles and deliberative practices, I thought only of student voice, voting, and the students’ ability to have a say in their education. However, when I learned about and broke down the capacities of agency, empathy, community, communication, and deliberation, I realized that these ideas are actually ever-present in a kindergarten.”

All of the participating teachers agreed that their understanding of citizenship changed from one that emphasized following rules and helping others to one that fostered student engagement in making decisions together about shared problems in the classroom community and beyond.

For more information about the practices used by these teachers, please go to https://www.kettering.org/blogs/kfnews. Additional resources are available at https://www.kettering.org/catalog/product/deliberation-classroom.

The Charles F. Kettering Foundation is a nonprofit operating foundation rooted in the American tradition of cooperative research. Kettering’s primary research question is, what does it take to make democracy work as it should? Kettering’s research is distinctive because it is conducted from the perspective of citizens and focuses on what people can do collectively to address problems affecting their lives, their communities, and their nation. Established in 1927 by inventor Charles F. Kettering, the foundation is a 501(c)(3) organization that does not make grants but engages in joint research with others. For more information about Kettering research and publications, please go to www.kettering.org.

For permission to repost this Democracy Rising entry, contact Sarah Murphy at smurphy@kettering.org.

Teaser photo credit: Author supplied.